Sleep and Economic Status Are Linked to Daily Life Stress in African-Born Blacks Living in America

Abstract

:1. Introduction

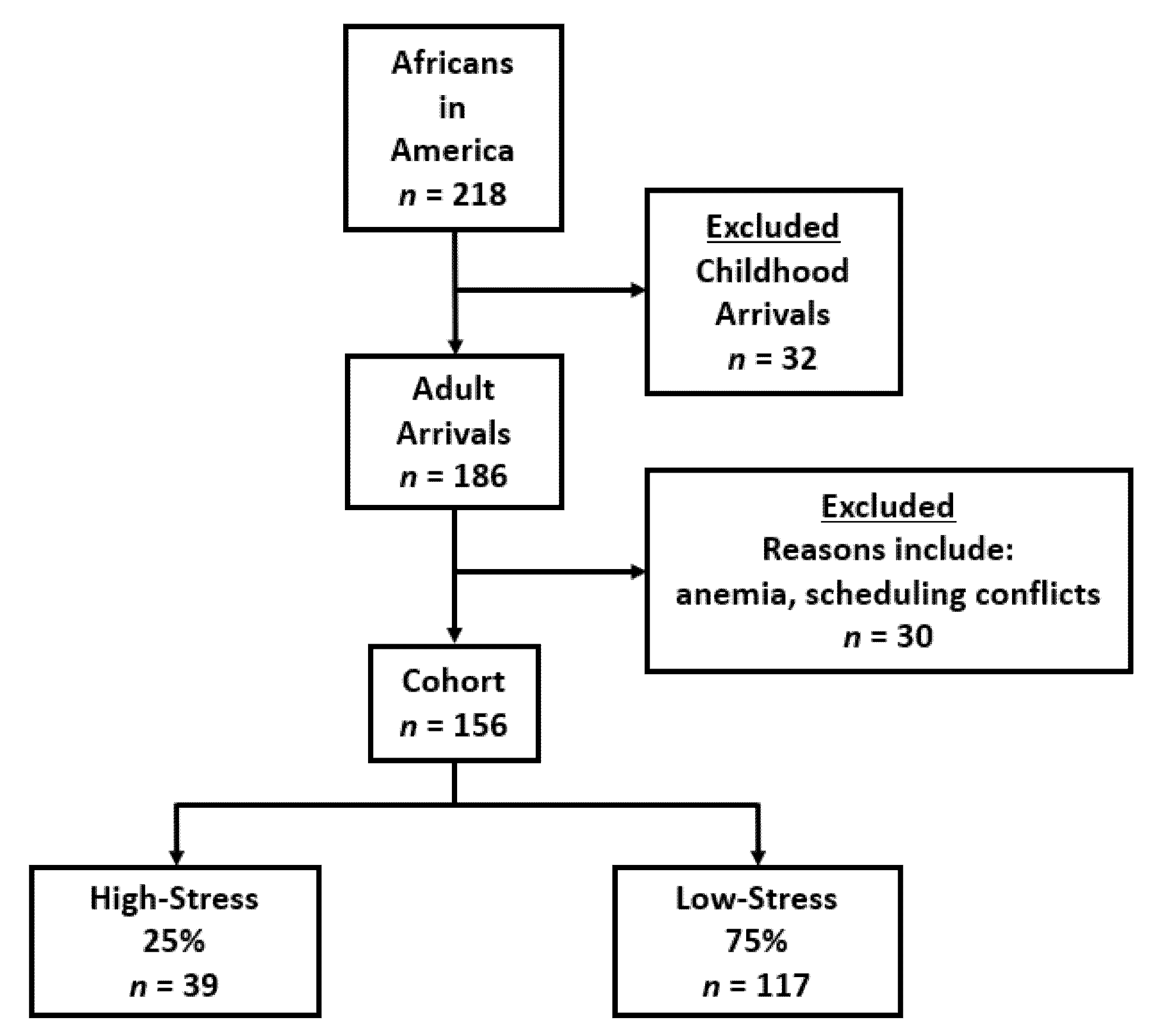

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Perceived Stress Scale

2.2. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

2.3. Social Variables

2.4. Assays

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. High and Low-Stress Group Comparisons

3.2. Odds of Being in the High-Stress Group

3.3. Perceived Stress and Sleep

4. Discussion

4.1. Income and Health Insurance

4.2. Duration of United States Residence

4.3. Life Partner

4.4. Sleep

4.5. Smoking

4.6. Chronic Life Stress

4.7. Education, Gender, Physical Activity and Alcohol Intake

4.8. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, M.; Lopez, G. Facts about Black Immigrants in the U.S. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/24/ (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Hormenu, T.; Shoup, E.M.; Osei-Tutu, N.H.; Hobabagabo, A.F.; DuBose, C.W.; Mabundo, L.S.; Chung, S.T.; Horlyck-Romanovsky, M.F.; Sumner, A.E. Stress Measured by Allostatic Load Varies by Reason for Immigration, Age at Immigration, and Number of Children: The Africans in America Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukaz, D.K.; Melby, M.K.; Papas, M.A.; Setiloane, K.; Nmezi, N.A.; Commodore-Mensah, Y. Diabetes and acculturation in African immigrants to the United States: Analysis of the 2010–2017 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Ethn. Health 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health; Spacapam, S., Ed.; Sage: Newbury, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B.S. Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esheverria-Estrada, C.; Batalova, J. Sub-Saharan African Immigrants in the United States. 2019. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/sub-saharan-african-immigrants-united-states-2018 (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Agyemang, C.; Sumner, A.E. Cardiometabolic Health in African Immigrants to the United States: A Call to Re-examine Research on African-descent Populations. Ethn. Dis. 2015, 25, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Utumatwishima, J.N.; Chung, S.T.; Bentley, A.R.; Udahogora, M.; Sumner, A.E. Reversing the tide—Diagnosis and prevention of T2DM in populations of African descent. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 14, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnethon, M.R.; Pu, J.; Howard, G.; Albert, M.A.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Bertoni, A.G.; Mujahid, M.S.; Palaniappan, L.; Taylor, H.A., Jr.; Willis, M.; et al. Cardiovascular Health in African Americans: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 136, e393–e423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ôunpuu, S.; Negassa, A.; Yusuf, S. INTER-HEART: A global study of risk factors for acute myocardial infarction. Am. Hear. J. 2001, 141, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, A.; Hawken, S.; Ôunpuu, S.; Sliwa, K.; Zubaid, M.; Almahmeed, W.A.; Blackett, K.N.; Sitthi-Amorn, C.; Sato, H.; Yusuf, S. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11,119 cases and 13,648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 2004, 364, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratin, C.; Beune, E.; Van Schalkwijk, D.; Meeks, K.; Smeeth, L.; Addo, J.; Aikins, A.D.-G.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; Bahendeka, S.; Mockenhaupt, F.P.; et al. Differential associations between psychosocial stress and obesity among Ghanaians in Europe and in Ghana: Findings from the RODAM study. Soc. Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2019, 55, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chilunga, F.P.; Henneman, P.; Meeks, K.A.; Beune, E.; Mendez, A.R.; Smeeth, L.; Addo, J.; Bahendeka, S.; Danquah, I.; Schulze, M.B.; et al. Prevalence and determinants of type 2 diabetes among lean African migrants and non-migrants: The RODAM study. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 020426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidulescu, A.; Din-Dzietham, R.; Coverson, D.L.; Chen, Z.; Meng, Y.-X.; Buxbaum, S.G.; Gibbons, G.H.; Welch, V.L. Interaction of sleep quality and psychosocial stress on obesity in African Americans: The Cardiovascular Health Epidemiology Study (CHES). BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Laethem, M.; Beckers, D.G.; Kompier, M.A.; Kecklund, G.; Bossche, S.N.V.D.; Geurts, S.A. Bidirectional relations between work-related stress, sleep quality and perseverative cognition. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 79, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Ukonu, N.; Cooper, L.A.; Agyemang, C.; Himmelfarb, C.D. The Association Between Acculturation and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Ghanaian and Nigerian-born African Immigrants in the United States: The Afro-Cardiac Study. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017, 20, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkson-Ocran, R.-A.N.; Szanton, S.L.; Cooper, L.A.; Golden, S.H.; Ahima, R.S.; Perrin, N.; Commodore-Mensah, Y. Discrimination Is Associated with Elevated Cardiovascular Disease Risk among African Immigrants in the African Immigrant Health Study. Ethn. Dis. 2020, 30, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrifa-Anane, E.; Aikins, A.D.-G.; Meeks, K.A.C.; Beune, E.; Addo, J.; Smeeth, L.; Bahendeka, S.; Stronks, K.; Agyemang, C. Physical Inactivity among Ghanaians in Ghana and Ghanaian Migrants in Europe. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 2152–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilunga, F.P.; Boateng, D.; Henneman, P.; Beune, E.; Requena-Méndez, A.; Meeks, K.; Smeeth, L.; Addo, J.; Bahendeka, S.; Danquah, I.; et al. Perceived discrimination and stressful life events are associated with cardiovascular risk score in migrant and non-migrant populations: The RODAM study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 286, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.Y.; Thoreson, C.K.; Ricks, M.; Courville, A.B.; Thomas, F.; Yao, J.; Katzmarzyk, P.; Sumner, A.E. Worse Cardiometabolic Health in African Immigrant Men than African American Men: Reconsideration of the Healthy Immigrant Effect. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2014, 12, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoup, E.M.; Hormenu, T.; Osei-Tutu, N.H.; Ishimwe, M.C.S.; Patterson, A.C.; DuBose, C.W.; Wentzel, A.; Horlyck-Romanovsky, M.F.; Sumner, A.E. Africans Who Arrive in the United States before 20 Years of Age Maintain Both Cardiometabolic Health and Cultural Identity: Insight from the Africans in America Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukegbu, U.J.; Castillo, D.C.; Knight, M.G.; Ricks, M.; Miller, B.V., III; Onumah, B.M.; Sumner, A.E. Metabolic syndrome does not detect metabolic risk in African men living in the U.S. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 2297–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Briker, S.M.; Aduwo, J.Y.; Mugeni, R.; Horlyck-Romanovsky, M.F.; DuBose, C.W.; Mabundo, L.S.; Hormenu, T.; Chung, S.T.; Ha, J.; Sherman, A.; et al. A1C Underperforms as a Diagnostic Test in Africans Even in the Absence of Nutritional Deficiencies, Anemia and Hemoglobinopathies: Insight from the Africans in America Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hobabagabo, A.F.; Osei-Tutu, N.H.; Hormenu, T.; Shoup, E.M.; DuBose, C.W.; Mabundo, L.S.; Ha, J.; Sherman, A.; Chung, S.T.; Sacks, D.B.; et al. Improved Detection of Abnormal Glucose Tolerance in Africans: The Value of Combining Hemoglobin A1c With Glycated Albumin. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2607–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimwe, M.C.S.; Wentzel, A.; Shoup, E.M.; Osei-Tutu, N.H.; Hormenu, T.; Patterson, A.C.; Bagheri, H.; DuBose, C.W.; Mabundo, L.S.; Ha, J.; et al. Beta-cell failure rather than insulin resistance is the major cause of abnormal glucose tolerance in Africans: Insight from the Africans in America study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2021, 9, e002447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagannathan, R.; DuBose, C.W.; Mabundo, L.S.; Chung, S.T.; Ha, J.; Sherman, A.; Bergman, M.; Sumner, A.E. The OGTT is highly reproducible in Africans for the diagnosis of diabetes: Implications for treatment and protocol design. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 170, 108523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Physical Activity Questionnaire. 2005. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Utumatwishima, J.N.; Baker, R.L.; Bingham, B.A.; Chung, S.T.; Berrigan, D.; Sumner, A.E. Stress Measured by Allostatic Load Score Varies by Reason for Immigration: The Africans in America Study. J. Racial Ethn. Health. Disparities 2017, 5, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC)—Africa Working Group; Kengne, A.P.; Bentham, J.; Zhou, B.; Peer, N.; Matsha, T.E.; Bixby, H.; Di Cesare, M.; Hajifathalian, K.; Lu, Y.; et al. Trends in obesity and diabetes across Africa from 1980 to 2014: An analysis of pooled population-based studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uncertainty Health Care. 2017. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2017/uncertainty-health-care.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Afulani, P.A.; Torres, J.M.; Sudhinaraset, M.; Asunka, J. Transnational ties and the health of sub-Saharan African migrants: The moderating role of gender and family separation. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 168, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Ukonu, N.; Obisesan, O.; Aboagye, J.K.; Agyemang, C.; Reilly, C.M.; Dunbar, S.B.; Okosun, I.S. Length of Residence in the United States is Associated With a Higher Prevalence of Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Immigrants: A Contemporary Analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, S.C.; Umer, A.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Davidov, D.; Abildso, C.G. Length of Residence and Cardiovascular Health among Afro-Caribbean Immigrants in New York City. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2018, 6, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, U.; Künzel, H.; Tröndle, K.; Rottenkolber, M.; Kohn, D.; Fugmann, M.; Banning, F.; Weise, M.; Sacco, V.; Hasbargen, U.; et al. Poor sleep quality is associated with impaired glucose tolerance in women after gestational diabetes. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 65, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, H.V.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; Iwelunmor, J.; Newsome, V.; Meeks, K.; Agyemang, C.; Jean-Louis, G. Sleep duration is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular outcomes: A pilot study in a sample of community dwelling adults in Ghana. Sleep Med. 2017, 34, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangwisch, J.E.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Boden-Albala, B.; Buijs, R.M.; Kreier, F.; Pickering, T.G.; Rundle, A.; Zammit, G.K.; Malaspina, D. Sleep Duration as a Risk Factor for Diabetes Incidence in a Large US Sample. Sleep 2007, 30, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.H.; Muldoon, M.F.; Jennings, J.R.; Buysse, D.J.; Flory, J.D.; Manuck, S.B. Self-Reported Sleep Duration is Associated with the Metabolic Syndrome in Midlife Adults. Sleep 2008, 31, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayfron-Benjamin, C.F.; Der Zee, A.H.M.-V.; Born, B.-J.V.D.; Amoah, A.G.B.; Meeks, K.A.C.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Schulze, M.B.; Spranger, J.; Danquah, I.; Smeeth, L.; et al. Association between C reactive protein and microvascular and macrovascular dysfunction in sub-Saharan Africans with and without diabetes: The RODAM study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, e001235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Li, S.; Pan, L.; Zhang, N.; Jia, C. Association of anxiety disorders with the risk of smoking behaviors: A meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 145, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesko, M.F.; Baum, C.F. The self-medication hypothesis: Evidence from terrorism and cigarette accessibility. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2016, 22, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ezzati, A.; Jiang, J.; Katz, M.J.; Sliwinski, M.J.; Zimmerman, M.E.; Lipton, R.B. Validation of the Perceived Stress Scale in a community sample of older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 29, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geronimus, A.T.; Hicken, M.; Keene, D.; Bound, J. “Weathering” and Age Patterns of Allostatic Load Scores Among Blacks and Whites in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. African Immigrant Population in U.S. Steadily Climbs. 2017. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/02/14/african-immigrant-population-in-u-s-steadily-climbs/ (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atas, D.B.; Sunbul, E.A.; Velioglu, A.; Tuglular, S. The association between perceived stress with sleep quality, insomnia, anxiety and depression in kidney transplant recipients during COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lan, M.; Li, H.; Yang, J. Perceived stress and sleep quality among the non-diseased general public in China during the 2019 coronavirus disease: A moderated mediation model. Sleep Med. 2020, 77, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creatore, M.I.; Moineddin, R.; Booth, G.; Manuel, D.H.; des Meules, M.; McDermott, S.; Glazier, R.H. Age- and sex-related prevalence of diabetes mellitus among immigrants to Ontario, Canada. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2010, 182, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piel, F.B.; Howes, R.E.; Patil, A.P.; Nyangiri, O.A.; Gething, P.W.; Bhatt, S.; Williams, T.N.; Weatherall, D.J.; Hay, S.I. The distribution of haemoglobin C and its prevalence in newborns in Africa. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piel, F.B.; Patil, A.P.; Howes, R.E.; Nyangiri, O.A.; Gething, P.W.; Dewi, M.; Temperley, W.H.; Williams, T.N.; Weatherall, D.J.; Hay, S.I. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: A contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet 2013, 381, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.R.; Yan, Y.; Jackson, J.S.; Anderson, N.B. Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters 1 | Cohort 100% (n = 156) | West 37% (n = 58) | Central 14% (n = 22) | East 2 49% (n = 76) | p-Value 2,3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Sex (% male) | 60% | 73% | 54% | 64% | 0.224 |

| Age (years) | 40 ± 10 | 40 ± 11 | 40 ± 11 | 40 ± 10 | 0.941 |

| Metabolic characteristics | |||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.9 ± 1.5 | 13.8 ± 1.5 | 13.9 ± 1.5 | 13.9 ± 1.5 | 0.964 |

| Sickle cell trait or HbC trait (%) | 14% | 19% | 18% | 7% | 0.081 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.6 ± 4.2 | 28.7 ± 4.2 | 26.9 ± 3.9 a * | 26.9 ± 4.2 | 0.042 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 91 ± 12 | 93 ± 11 | 88 ± 10 | 91 ± 12 | 0.231 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 117 ± 12 | 118 ± 11 | 119 ± 10 | 118 ± 10 | 0.630 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 71 ± 9 | 71 ± 9 | 71 ± 10 | 71 ± 9 | 0.869 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 94 ± 16 | 96 ± 23 | 95 ± 8 | 92 ± 10 | 0.455 |

| A1C (%) | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 0.609 |

| Diabetes (%) | 8% | 10% | 5% | 7% | 0.602 |

| Scores | |||||

| Perceived stress score (PSS) | 12 ± 7 | 11 ± 6 | 12 ± 7 | 12 ± 7 | 0.808 |

| Pittsburgh sleep quality score (PSQI) | 4.8 ± 2.9 | 4.9 ± 3.0 | 5.1 ± 3.3 | 4.6 ± 2.8 | 0.726 |

| Socioeconomic | |||||

| Income < 40 k | 54% | 57% | 77% a * | 53% | 0.046 |

| No health insurance | 39% | 40% | 46% | 37% | 0.762 |

| No partner (%) | 45% | 48% | 50% | 41% | 0.601 |

| Education (no college degree) | 23% | 14% | 27% | 29% | 0.105 |

| Adverse health behaviors | |||||

| Smoking | 5% | 5% | 5% | 5% | 0.991 |

| Alcohol ≥ 1 drink/week | 22% | 24% | 18% | 22% | 0.850 |

| Sedentary | 22% | 24% | 18% | 22% | 0.850 |

| Migration factors | |||||

| Age at United States entry (years) | 31 ± 9 | 30 ± 9 | 32 ± 9 | 32 ± 9 | 0.542 |

| High risk immigration reason 4 | 24% | 19% | 41% | 24% | 0.122 |

| Years in United States (years) | 9 ± 10 | 10 ± 11 | 9 ± 8 | 9 ± 8 | 0.648 |

| United States residence < 10 years | 64% | 60% | 59% | 68% | 0.546 |

| Variable 1 | Total 100% n = 156 | High-Stress 2 25% n = 39 | Low-Stress 75% n = 117 | p-Value 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Sex (% male) | 60% | 56% | 62% | 0.571 |

| Age (years) | 40 ± 10 | 38 ± 10 | 41 ± 10 | 0.242 |

| Metabolic characteristics | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.9 ± 1.5 | 13.7 ± 1.7 | 13.9 ± 1.4 | 0.386 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.6 ± 4.2 | 27.7 ± 4.0 | 27.5 ± 4.0 | 0.863 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 91 ± 12 | 91 ± 12 | 91 ± 12 | 0.942 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 117 ± 12 | 117 ± 13 | 117 ± 12 | 0.852 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 71 ± 9 | 71 ± 9 | 71 ± 9 | 0.848 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 94 ± 16 | 92 ± 9 | 95 ± 18 | 0.350 |

| A1C (%) | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 0.260 |

| Diabetes | 8% | 8% | 8% | 0.999 |

| Scores | ||||

| Perceived stress scale | 12 ± 7 | 21 ± 4 | 9 ± 4 | <0.001 |

| Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) | 4.8 ± 2.9 | 6.2 ± 2.9 | 4.3 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Poor sleep quality (PSQI > 5) (%) | 39% | 64% | 30% | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic | ||||

| Income < 40 k (%) | 54% | 85% | 44% | <0.001 |

| No health insurance (%) | 39% | 67% | 30% | <0.001 |

| No partner (%) | 45% | 62% | 39% | 0.016 |

| Education (no college degree) | 23% | 28% | 21% | 0.380 |

| Adverse health behaviors | ||||

| Smoking | 5% | 13% | 3% | 0.012 |

| Alcohol ≥ 1 drink/wk | 22% | 18% | 24% | 0.438 |

| Sedentary | 22% | 21% | 23% | 0.740 |

| Migration factors | ||||

| Age at United States entry (years) | 31 ± 9 | 31 ± 9 | 31 ± 9 | 0.779 |

| High Risk Immigration Reason 4 | 24% | 28% | 23% | 0.518 |

| Years in United States (years) | 9 ± 10 | 7 ± 9 | 10 ± 10 | 0.160 |

| United States residence < 10 years | 64% | 67% | 60% | 0.054 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Poor sleep quality (PSQI > 5) | 5.11 (2.07, 12.62) | <0.001 |

| Income < 40 k | 5.03 (1.75, 14.47) | 0.002 |

| No health insurance | 3.01 (1.19, 8.56) | 0.019 |

| Single (no life partner) | X | 0.070 |

| Alcohol intake (≥1 drink/wk) | X | 0.260 |

| education 1 | X | 0.424 |

| High risk immigration 2 | X | 0.669 |

| Sedentary | X | 0.743 |

| Gender (male) | X | 0.856 |

| United States Residence < 10 years | X | 0.890 |

| PSQI Components | β-Coefficient (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep Disturbance | 3.51 (1.87, 5.16) | <0.001 |

| Daytime Dysfunction | 2.27 (1.09, 3.45) | <0.001 |

| Subjective Sleep Quality | 2.07 (0.75, 3.39) | 0.002 |

| Sleep Duration | −0.86 (−1.08, 0.10) | 0.078 |

| Sleep Medicine | −1.58 (−3.40, 0.26) | 0.091 |

| Sleep Latency | 0.71 (−0.22, 1.65) | 0.122 |

| Habitual Sleep Efficiency | −0.44 (−1.60, 0.74) | 0.463 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Waldman, Z.C.; Schenk, B.R.; Duhuze Karera, M.G.; Patterson, A.C.; Hormenu, T.; Mabundo, L.S.; DuBose, C.W.; Jagannathan, R.; Whitesell, P.L.; Wentzel, A.; et al. Sleep and Economic Status Are Linked to Daily Life Stress in African-Born Blacks Living in America. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052562

Waldman ZC, Schenk BR, Duhuze Karera MG, Patterson AC, Hormenu T, Mabundo LS, DuBose CW, Jagannathan R, Whitesell PL, Wentzel A, et al. Sleep and Economic Status Are Linked to Daily Life Stress in African-Born Blacks Living in America. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052562

Chicago/Turabian StyleWaldman, Zoe C., Blayne R. Schenk, Marie Grace Duhuze Karera, Arielle C. Patterson, Thomas Hormenu, Lilian S. Mabundo, Christopher W. DuBose, Ram Jagannathan, Peter L. Whitesell, Annemarie Wentzel, and et al. 2022. "Sleep and Economic Status Are Linked to Daily Life Stress in African-Born Blacks Living in America" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052562

APA StyleWaldman, Z. C., Schenk, B. R., Duhuze Karera, M. G., Patterson, A. C., Hormenu, T., Mabundo, L. S., DuBose, C. W., Jagannathan, R., Whitesell, P. L., Wentzel, A., Horlyck-Romanovsky, M. F., & Sumner, A. E. (2022). Sleep and Economic Status Are Linked to Daily Life Stress in African-Born Blacks Living in America. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052562