Determinants of Changes in Women’s and Men’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior across the Transition to Parenthood: A Focus Group Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Question Guide

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Changes in PA and SB during Pregnancy and Postpartum

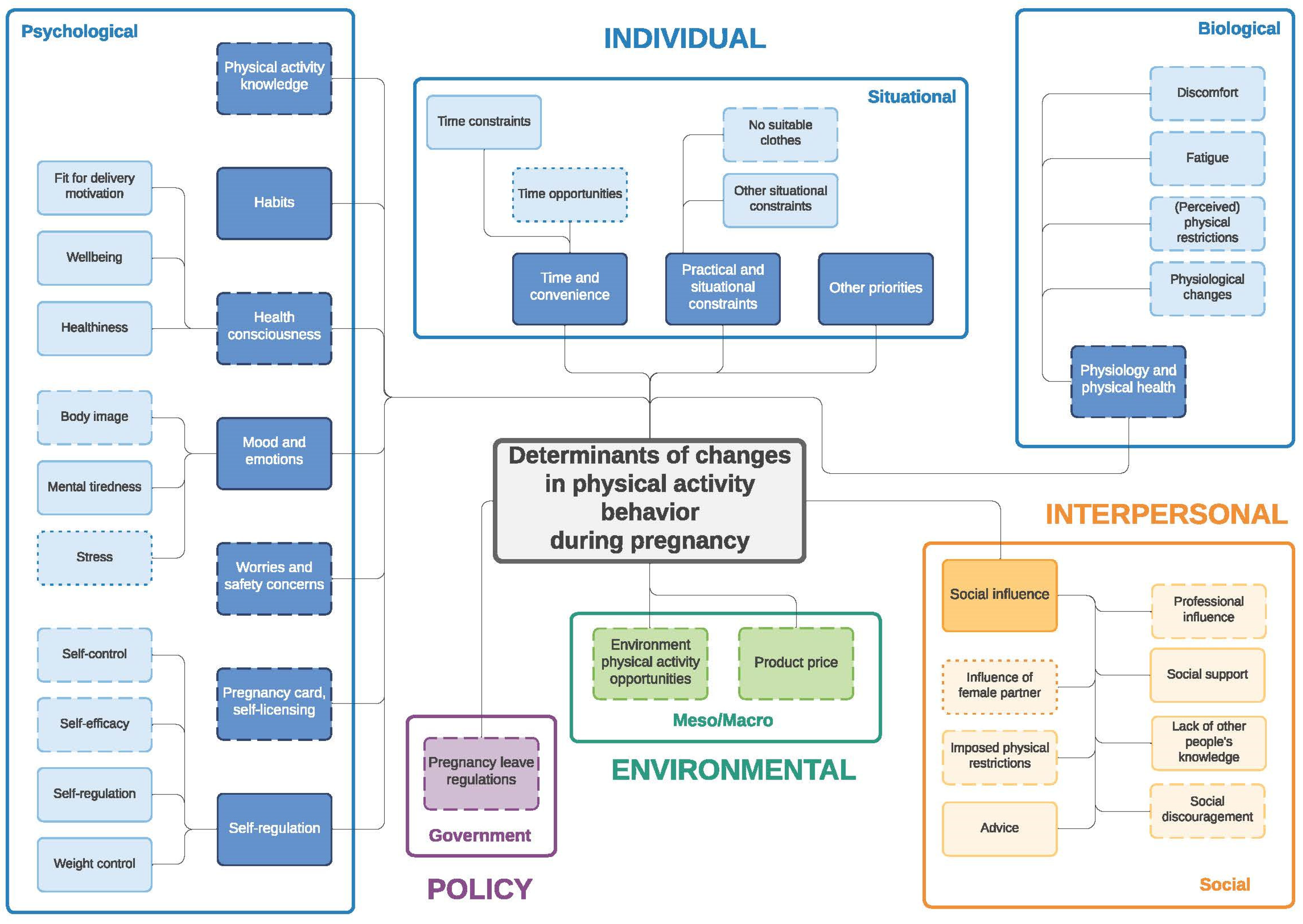

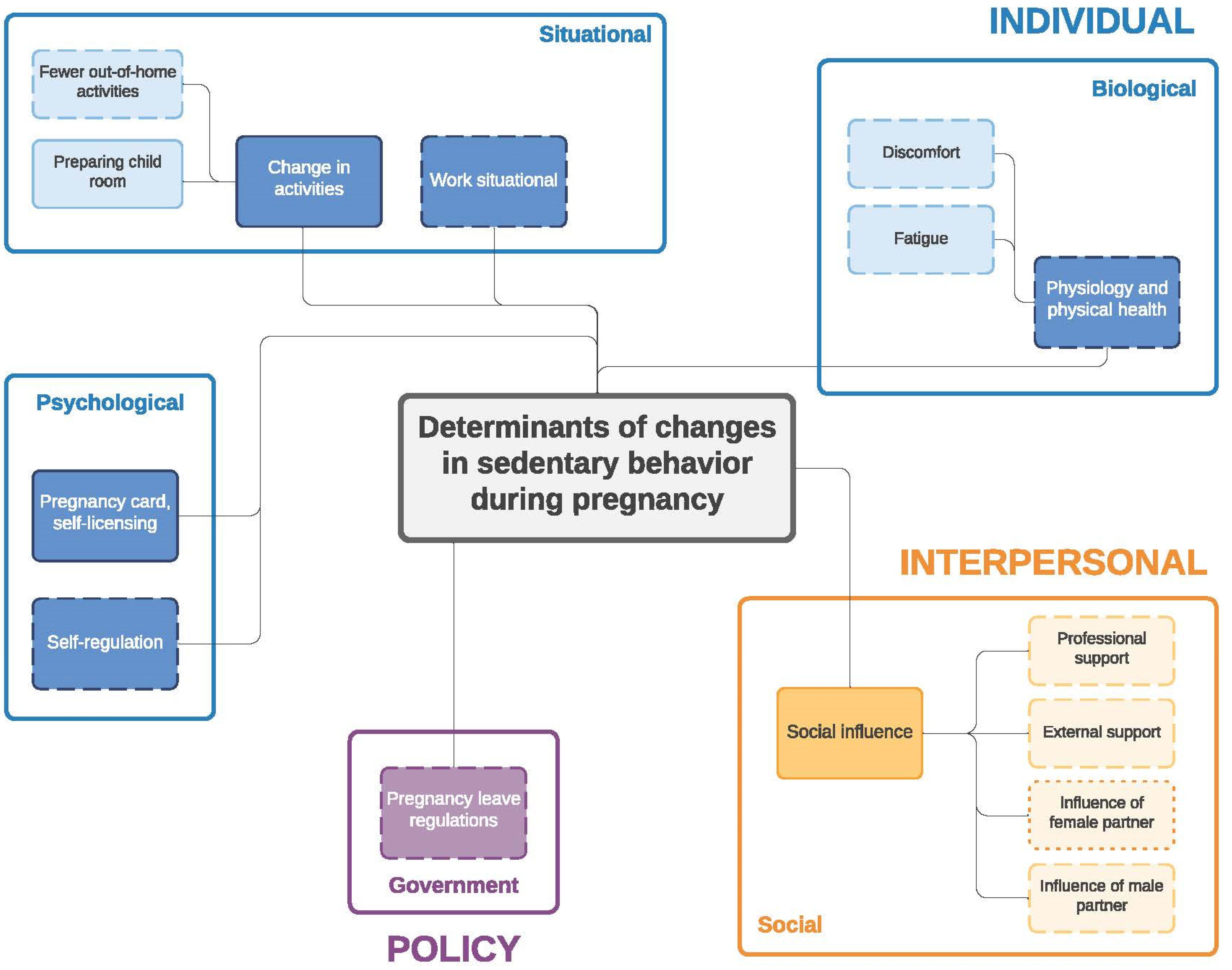

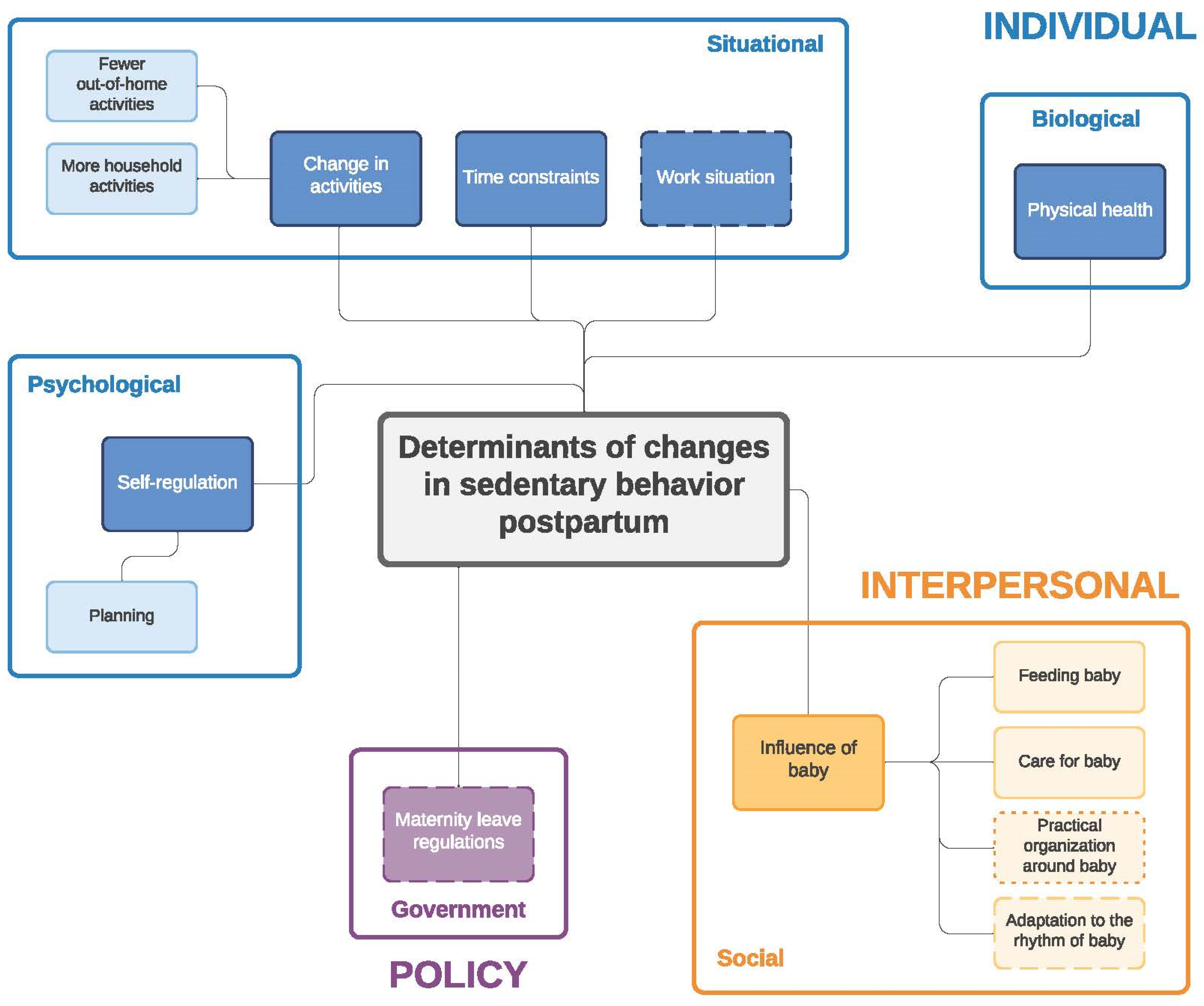

3.2. Determinants of Changes in PA and SB during Pregnancy and Postpartum

3.2.1. Individual Level (PA/SB)

Psychological (PA/SB)

Situational (PA/SB)

Biological (PA/SB)

3.2.2. Interpersonal Level (PA/SB)

Social Influence—During Pregnancy (PA/SB) and Postpartum (PA)

Influence of Baby—Postpartum (PA/SB)

3.2.3. Environmental Level (PA)

Meso/Macro—During Pregnancy (PA)

Product Price—During Pregnancy and Postpartum (PA)

3.2.4. Policy Level (PA/SB)

Government—During Pregnancy and Postpartum (PA/SB)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davenport, M.H.; Ruchat, S.M.; Poitras, V.J.; Jaramillo Garcia, A.; Gray, C.E.; Barrowman, N.; Skow, R.J.; Meah, V.L.; Riske, L.; Sobierajski, F.; et al. Prenatal exercise for the prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Polán, M.; Franco, E.; Silva-José, C.; Gil-Ares, J.; Pérez-Tejero, J.; Barakat, R.; Refoyo, I. Exercise During Pregnancy and Prenatal Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 640024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogozińska, E.; Marlin, N.; Betrán, A.P.; Astrup, A.; Barakat, R.; Bogaerts, A.; Jose, G.C.; Devlieger, R.; Dodd, J.M.; El Beltagy, N.; et al. Effect of diet and physical activity based interventions in pregnancy on gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes: Meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed) 2017, 358, j3119. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, S.L.; Pudwell, J.; Surita, F.G.; Adamo, K.B.; Smith, G.N. The effect of physical exercise strategies on weight loss in postpartum women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyatos-León, R.; Garcia-Hermoso, A.; Sanabria-Martínez, G.; Alvarez-Bueno, C.; Sánchez-López, M.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Effects of exercise during pregnancy on mode of delivery: A meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2015, 94, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, M.H.; Meah, V.L.; Ruchat, S.M.; Davies, G.A.; Skow, R.J.; Barrowman, N.; Adamo, K.B.; Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Jaramillo Garcia, A.; et al. Impact of prenatal exercise on neonatal and childhood outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnild, J.M.; Hinshaw, K.; Pollard, T. Associations of sedentary time and self-reported television time during pregnancy with incident gestational diabetes and plasma glucose levels in women at risk of gestational diabetes in the UK. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieberger, A.M.; Desoye, G.; Stolz, E.; Hill, D.J.; Corcoy, R.; Simmons, D.; Harreiter, J.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Dunne, F.; Devlieger, R.; et al. Less sedentary time is associated with a more favourable glucose-insulin axis in obese pregnant women—a secondary analysis of the DALI study. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Poppel, M.N.M.; Simmons, D.; Devlieger, R.; van Assche, F.A.; Jans, G.; Galjaard, S.; Corcoy, R.; Adelantado, J.M.; Dunne, F.; Harreiter, J.; et al. A reduction in sedentary behaviour in obese women during pregnancy reduces neonatal adiposity: The DALI randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fazzi, C.; Saunders, D.H.; Linton, K.; Norman, J.E.; Reynolds, R.M. Sedentary behaviours during pregnancy: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, A.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Shields, N.; Frawley, H.C. Attitudes, barriers and enablers to physical activity in pregnant women: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2018, 64, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, C.F.; Nascimento, S.L.D.; Helmo, F.R.; Monteiro, M.L.G.D.R.; Dos Reis, M.A.; Corrêa, R.R.M. An overview of maternal and fetal short and long-term impact of physical activity during pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 295, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesketh, K.R.; Evenson, K.R.; Prevalence of, U.S. Pregnant Women Meeting 2015 ACOG Physical Activity Guidelines. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, e87–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lindqvist, M.; Lindkvist, M.; Eurenius, E.; Persson, M.; Ivarsson, A.; Mogren, I. Leisure time physical activity among pregnant women and its associations with maternal characteristics and pregnancy outcomes. Sex. Reprod. Health 2016, 9, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, M.A.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Kleinman, K.P.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Peterson, K.E.; Gillman, M.W. Predictors of change in physical activity during and after pregnancy: Project Viva. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hesketh, K.R.; Evenson, K.R.; Stroo, M.; Clancy, S.M.; Østbye, T.; Benjamin-Neelon, S.E. Physical activity and sedentary behavior during pregnancy and postpartum, measured using hip and wrist-worn accelerometers. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 10, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engberg, E.; Alen, M.; Kukkonen-Harjula, K.; Peltonen, J.E.; Tikkanen, H.O.; Pekkarinen, H. Life events and change in leisure time physical activity: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.J.; Heesch, K.; Miller, Y.D. Life Events and Changing Physical Activity Patterns in Women at Different Life Stages. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 37, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darwin, Z.; on behalf of the Born and Bred in Yorkshire (BaBY) Team; Galdas, P.; Hinchliff, S.; Littlewood, E.; McMillan, D.; McGowan, L.; Gilbody, S. Fathers’ views and experiences of their own mental health during pregnancy and the first postnatal year: A qualitative interview study of men participating in the UK Born and Bred in Yorkshire (BaBY) cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, S.; Malone, M.; Sandall, J.; Bick, D. Mental health and wellbeing during the transition to fatherhood: A systematic review of first time fathers’ experiences. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2018, 16, 2118–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saxbe, D.; Corner, G.W.; Khaled, M.; Horton, K.; Wu, B.; Khoddam, H.L.; Corner, G.W. The weight of fatherhood: Identifying mechanisms to explain paternal perinatal weight gain. Health Psychol. Rev. 2018, 12, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pot, N.; Keizer, R. Physical activity and sport participation: A systematic review of the impact of fatherhood. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leppänen, M.; Aittasalo, M.; Raitanen, J.; Kinnunen, T.I.; Kujala, U.M.; Luoto, R. Physical Activity During Pregnancy: Predictors of Change, Perceived Support and Barriers Among Women at Increased Risk of Gestational Diabetes. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 2158–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellows-Riecken, K.H.; Rhodes, R.E. A birth of inactivity? A review of physical activity and parenthood. Prev. Med. 2007, 46, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.; Downs, S.D.; Riecken, B.K. Delivering inactivity: A review of physical activity and the transition to motherhood. Prev. Med. 2008, volume, 105–127. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, S. Pregnancy: A “teachable moment” for weight control and obesity prevention. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 135.e1–135.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coll, C.V.; Domingues, M.; Gonçalves, H.; Bertoldi, A.D. Perceived barriers to leisure-time physical activity during pregnancy: A literature review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 20, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 20, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.N.; O’Sullivan, A.J. Sex Differences in Energy Metabolism Need to Be Considered with Lifestyle Modifications in Humans. J. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 2011, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Richardson, M.; Jacobs, D.R.; Leon, A.S. Gender differences in physical activity. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 1993, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. Qualitative Research; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Versele, V.; Stok, F.M.; Aerenhouts, D.; Deforche, B.; Bogaerts, A.; Devlieger, R.; Clarys, P.; Deliens, T. Determinants of changes in women’s and men’s eating behavior across the transition to parenthood: A focus group study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murray-Davis, B.; Grenier, L.; Atkinson, S.A.; Mottola, M.F.; Wahoush, O.; Thabane, L.; Xie, F.; Vickers-Manzin, J.; Moore, C.; Hutton, E.K. Experiences regarding nutrition and exercise among women during early postpartum: A qualitative grounded theory study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dieberger, A.M.; van Poppel, M.N.M.; Watson, E.D. Baby Steps: Using Intervention Mapping to Develop a Sustainable Perinatal Physical Activity Healthcare Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.L.; Vamos, C.A.; Daley, E.M. Physical activity during pregnancy and the role of theory in promoting positive behavior change: A systematic review. J. Sport Health Sci. 2015, 6, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Findley, A.; Smith, D.M.; Hesketh, K.; Keyworth, C. Exploring womens’ experiences and decision making about physical activity during pregnancy and following birth: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarke, E.P.; Gross, H. Women’s behaviour, beliefs and information sources about physical exercise in pregnancy. Midwifery 2004, 20, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, A.; Smith, A.D.; Llewellyn, C.H.; Croker, H. Investigating partner involvement in pregnancy and identifying barriers and facilitators to participating as a couple in a digital healthy eating and physical activity intervention. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, M.C.; Allen-Walker, V.; McGirr, C.; Rooney, C.; Woodside, J.V. Weight loss after pregnancy: Challenges and opportunities. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2018, 31, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karita, K.; Kitada, M. Political Measures against Declining Birthrate—Implication of Good Family Policies and Practice in Sweden or France. Nippon Eiseigaku Zasshi Jpn. J. Hyg. 2018, 73, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaams Instituut Gezond Leven, Hoeveel Beweeg Je Best als je Zwanger of Pas Bevallen Bent? 2021. Available online: https://www.gezondleven.be/themas/beweging-sedentair-gedrag/beweegadvies-voor-zwangere-en-pas-bevallen-vrouwen/hoeveel-beweeg-je-best-als-je-zwanger-of-pas-bevallen-bent (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Regber, S.; Novak, M.; Eiben, G.; Lissner, L.; Hense, S.; Sandström, T.Z.; Ahrens, W.; Mårild, S. Assessment of selection bias in a health survey of children and families—The IDEFICS Sweden-study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Questions about Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior during Pregnancy | Questions about Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior during the Postpartum Period |

|---|---|

| 1. Think about the period before pregnancy/before the pregnancy of your partner; did your physical activity/sedentary behavior change during pregnancy/during the pregnancy of your partner, and if yes, how and to what extent? | 1. Think about the period before pregnancy/before the pregnancy of your partner; did your physical activity/sedentary behavior change since you became a mother/father, and if yes, how and to what extent? |

| 2. Which factors have caused these changes in physical activity/sedentary behavior during pregnancy? | 2. Which factors have caused these changes in physical activity/sedentary behavior since your child was born? |

| 3. Which factors do you think have had the greatest influence on these changes? | 3. Which factors do you think have had the greatest influence on these changes? |

| Focus Groups on Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior during Pregnancy | Focus Groups on Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior during the Postpartum Period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Total sample (n (%)) | 22 (55) | 20 (45) | 16 (50) | 16 (50) |

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 30.1 ± 2.5 | 31.6 ± 2.5 | 30.3 ± 2.0 | 31.7 ± 3.5 |

| Self-reported pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 22.7 ± 3.1 | 24.0 ± 4.5 | 23.3 ± 4.7 | 25.0 ± 2.4 |

| Respondents with a higher education (%) | 81.8 | 75.0 | 93.8 | 87.5 |

| Respondents reporting to be in good to very good health (%) | 100 | 100 | 62.6 | 81.3 |

| Respondents reporting healthy to totally healthy eating pattern (%) | 77.3 | 80.0 | 93.8 | 62.6 |

| Respondents reporting being active for at least 30 min/day for 5 days or more during the last 7 days (%) | 49.9 | 45.0 | 6.3 | 37.5 |

| % non-smokers (% ex-smokers) | 100 (4.5) | 100 (40.0) | 100 (0.0) | 100 (12.5) |

| Expecting parents (n) | 15 | 14 | / | / |

| Gestational age (weeks, mean ± SD) | 28.4 ± 8.1 | 28.2 ± 8.6 | / | / |

| Parents with child (n) * | 7 | 6 | 16 | 16 |

| Age of the newborn (weeks, mean ± SD) | 9.6 ± 2.8 | 9.8 ± 5.2 | 34.8 ± 14.7 | 32.6 ± 15.3 |

| During Pregnancy | Postpartum |

|---|---|

| 1. Decrease in PA and increase in SB | |

| Decrease in PA: - Daily activity e.g., less active because staying more at home for ‘a lazy day’ - Intensity e.g., walking instead of running - Leisure time PA e.g., not going to gym classes anymore - Transport-related PA e.g., by car instead of bike - Work related PA e.g., adjusted work | Decrease in PA: - Intensity, frequency and duration of PA - Leisure time PA e.g., stop doing dance classes together as a couple |

| Increase in SB: - Prolonged sitting time - Doing less e.g., fewer out-of-home activities - Extra rest e.g., lying down during the day | Increase in SB: - Leisure-time-related SB e.g., resting/television watching when the baby is asleep - Forced sitting time e.g., when the baby falls asleep in one’s arms, while breastfeeding |

| 2. Increase in PA and decrease in SB | |

| Increase in PA: - Leisure time PA e.g., more leisure-time PA | Increase in PA: - Transport-related PA e.g., more active transportation by bike - Leisure time PA e.g., doing sports when the baby is in daycare - Household-related PA - e.g., more walking around to do chores in the house - Child related PA e.g., playing with the baby |

| Decrease in SB: - SB at home e.g., preparing child room instead of sitting | Decrease in SB: - Household-related SB e.g., doing household tasks instead of sitting - Leisure-time-related SB e.g., less time to sit together in the sofa |

| 3. Shift in PA and SB | |

| Shift in: - Moments/timing of PA e.g., only time for walking during the weekend - People with whom you engage in PA e.g., activity together with partner decreased - Type of PA e.g., start swimming, workouts through YouTube - Sedentary bouts e.g., standing up more or less often | Shift in: - Moments/timing of PA e.g., earlier in the morning or later at night, less spontaneous - Organization of PA e.g., taking turns to go for sport - Type of PA e.g., running instead of gym classes - Sedentary bouts e.g., standing up more often to change diapers or taking care of the baby |

| Subcategories of Psychological Level | Quotes during Pregnancy | Quotes during the Postpartum Period |

|---|---|---|

| Physical activity knowledge | Quote PA1 (pregnant woman 5): “I managed to continue exercising, because at the beginning of my pregnancy I asked a sports coach for recommendations about what I could and could not do”. Quote PA2 (pregnant women 8): “I really asked the gynecologist every time ‘I’m still jogging, is that still allowed?’ because I felt very hesitant about whether that was still allowed”. | Quote PA3 (first-time mother 16): “I am at a point that I would like to do some sports, but I don’t know what I can do”. |

| Habits | Quote PA4 (pregnant woman 2): “For me it was because of my pelvis. If you have to work, walk around all day, cycle home, in the evening there are cooking classes where you also have to stand up all the time; I felt this in my pelvis. Now it is better, but I don’t think I will start again doing sports”. | |

| Health consciousness | Quote PA5 (pregnant woman 4)—fit for delivery motivation: “They say that giving birth is top sport. I truly believe that if you can start the delivery at a good level of fitness, it makes a huge difference”. Quote PA6 (pregnant woman 22)—wellbeing: “I did these YouTube workouts. You knew that after coming home, either you stay up for 20 more minutes to move your arms and legs up and down, or you settle yourself on the sofa, not to come out anymore. And afterwards it felt good, I often felt better when I did the effort to do these exercises”. | |

| Mood and emotions | Quote PA7 (pregnant woman 15): “During my last trimester I did absolutely no sport activities. Because I was exhausted, both physically as well as mentally, I didn’t feel like it then”. Quote PA8 (expecting father 8): “I had to lower my exercise goals compared to what I actually wanted, because mentally you do not have the peace anymore, you do not have the mental freedom to go for it as hard as you used to do”. | |

| Worries and safety concerns | Quote PA9 (pregnant woman 13): “You start thinking that playing football could be pretty dangerous. If you get a ball in your belly, or you go into a duel and you get an elbow; you do not want to take such a risk”. Quote PA10 (pregnant woman 22): “In my first trimester I just couldn’t do any sports. But now, I could do e.g., Zumba again, but I don’t dare to do it yet. Because I still notice that I get tired very fast and my fitness level is not what it used to be, and two weeks ago I fainted in the supermarket. So now I am afraid, going exercising for one hour, I don’t dare to do that anymore”. | Quote PA11 (first-time mother 16): “I used to dance once a week. I stopped doing that. (…) My pelvic floor has not recovered completely yet. I have had some problems and that makes me afraid of starting again with e.g., jumping”. |

| Self-licensing | Quote PA12 (pregnant women 17 and 18): Pregnant woman 18: “The nice thing is also that if you cancel something because you are too tired, nobody blames you for that”. Pregnant woman 17: “Indeed, pregnancy card!” | |

| Self-regulation | Quote PA13 (expecting father 10 about partner)—self-control: “I go running and swimming. I try to take her with me, but I have noticed that she has less desire to come with me”. Quote PA14 (pregnant woman 10)—self-efficacy: “I stayed home and didn’t go to work because I literally was nailed to my couch or bed. Afterwards it was very difficult to start moving again. And it remains very difficult for me”. Quote PA15 (expecting father 20)—self-regulation: “This is my goal, I try to get in shape by the time the baby is there, and then I have to make sure I can maintain this”. Quote SB1 (pregnant woman 17)—planning: “Yes, we normally went to do several things, but then I was like ‘Oh, never mind, the sofa is way too attractive’”. | Quote PA16 (first-time father 7 about partner)—weight control: “Actually, my wife increased her physical activity levels, with e.g., aqua-gym, because she realized that she gained weight. But it was more difficult to lose it again compared to earlier, back then she used to lose her weight easily when being active”. Quote PA17 (first-time father 14)—planning (PA): “I used to go running at least once or twice a week, and once swimming. Swimming is not an option anymore, running, once every second week. (…) I think that if I were to organize that, I would manage to do it again”. Quote SB2 (first-time father 11)—planning: “It is too tempting, if you are at home to just sit on the sofa and turn the television on, and turn her [the baby] around so she doesn’t face it”. Quote PA18 (first-time mother 15)—habituality of exercise: “I work in a healthcare setting, and once I started working again, my activity levels increased. (…) And I really noticed that when I restarted working, I also felt like moving more, just because I had to move again”. |

| Parenthood perceptions and responsibilities | Quote PA19 (first-time father 11)—barriers to leave child: “In some way I feel guilty when I’m not around enough, and it’s not because my wife tells me so, it is just for myself, when you have barely seen him [child], that is really not ok”. Quote PA20 (first-time father 4)—barriers to self-care: “If you think about it, it gives you a strange feeling, yes I want to go and do sports, but it is also very selfish, because it’s a moment that I don’t want to take care of the little one, while he [the baby] has become the focus of your life right now, because he [the baby] cannot do anything yet”. Quote PA21 (first-time mother 5)—barriers to ask for help: “Looking for a babysitter when you want to engage in sports is stupid, because it should be part of your normal life and that is nothing that requires a babysitter. So we don’t take a babysitter for that, but as a result we exercise half as much as before, so actually it should be a reason to take a babysitter, but it is a barrier”. Quote PA22 (first-time father 10 and first-time mother 16)—barriers to self-care: First-time father 10: “I think that especially women have more of a sense of responsibility, the feeling they have to be the one to take care of the child. As a man, you have more freedom and you can still do your things, your sports and hobbies. But as a woman, you have to think about all these practical things for the baby”. First-time mother 16: “I think that’s very much the case with me. I quickly feel like I’m being selfish when I do that. (…) If I want to go and do sports then I have to find a babysitter, I have to take care of his [the baby] food etc., and then I think ‘Never mind, I’ll just do it myself’. Then I also do not have to bother someone with this. I also feel like this is my task”. |

| Subcategories of Situational Level | Quotes during Pregnancy | Quotes during the Postpartum Period |

|---|---|---|

| Time and convenience | Quote PA23 (expecting father 7 and 11)—time opportunities: Expecting father 11: “She [pregnant partner] was constantly tired, and then I just relaxed with her”. Expecting father 7: “I’ve tried not to do that, I told her ‘You can just lie down on the sofa, and I will go and do some sports’. So I took advantage of that and went to do something else”. | Quote PA24 (first-time father 14)—time constraints: “Before, if I came home earlier than half past 8, I would think ‘It’s still a bit early to settle on the sofa, I’m going for a run’. And now, if I come home at half past 8, you have your child, it is nice, you are playing with him for half an hour, and then afterwards it got too late again to engage in sports activities. Playing with your child is also a nice distraction after work. I guess if I would organize myself better, I would manage to exercise again as well”. |

| Practical and situational constraints | Quote PA25 (pregnant woman 3)—no suitable sport clothes: “I have to invest in sports clothes. A couple of weeks ago we wanted to go to the gym, and my pants were just too tight. So I really was discouraged to go there and spend an hour working out”. Quote PA26 (expecting father 9)—other situational constraints: “Once the baby will be here, I won’t have time anyway. So I will have to choose what I’ll do, continue playing football or go running, I won’t be able to do both of these sports. So I am not going to start training for that now either, because in six months it will stop anyway”. | Quote PA27 (first-time father 1)—practical issues: “I used to go climbing. This year, I was actually too late to register. That is why I haven’t been able to do that, even though I really wanted to. I know, it is stupid. (…) It was probably because of…, I don’t want to blame [name baby], but otherwise I would have thought about it earlier”. Quote PA28 (first-time father 6)—organizational issues: “We used to dance once a week, but from a practical point of view it is not possible anymore. If you have to sacrifice one of the activities you do, it’s the dancing you choose, because then I prefer to go exercising. The dancing is nice, but it’s more like a relaxed hobby, whereas the exercising is maybe something you need more”. |

| Other priorities | Quote PA29 (pregnant woman 4): “All those to do’s, so yes when you go through your to-do list, yoga is the least important one on your list”. | Quote PA30 (first-time mother 5): “What I underestimated was that in advance I thought that I definitely wanted to continue exercising, because I believe doing sports is very important. But you can’t estimate that after… yes, your priorities are just completely different. You want to be with your child, you also would like to go do sports, but you just prefer to be with your child”. |

| Change in activities | Quote SB3 (expecting father 13): “At this moment we are busy preparing the child’s room, as we are making the cabinets ourselves, it is not so quiet anymore during the weekends, on the contrary, we’re mostly busy, especially working”. | Quote SB4 (first-time mother 4): “I will not sit down on the sofa as easily anymore as before and just watch television, because I have much more things to do in the household, and it makes me walk around much more as well”. |

| Work situational | Quote SB5 (pregnant woman 15): “When I was working, I was moving around all the time, and now it is already 3 weeks since I’m at home that I’m sleeping an extra hour in the morning and I also sit more throughout the day”. |

| Subcategories of Biological Level | Quotes during Pregnancy | Quotes during the Postpartum Period |

|---|---|---|

| Physiology | Quote SB6 (pregnant woman 5)—discomfort: “At my job I don’t sit much and as a self-employed person I kept on working. But I would sit down more often in between, if I noticed that it had been a bit too much, I just sat down and let my patients do more by themselves during a therapy session. But in the evening, I had to interrupt the sitting time. If I sat down too long, I would get really restless”. Quote PA32 (pregnant woman 19)—physiological changes: “I’m already feeling shortness of breath when I go up the stairs. I’m ashamed, this is not me, where did my physical fitness level go?” Quote PA33 (pregnant woman 18)—perceived physical restrictions: “My motion space; I did not expect that my belly would have such an impact on my normal movements. Sometimes I forget that it’s there, and I crash into something or I don’t fit through somewhere I would normally fit through…” | Quote PA31 (first-time father 11)—fatigue: “Yes, fatigue is an important factor of course, going for a run with a tired body, all my trainings are difficult nowadays, that used to go better, but now my running tempo is much lower than what it used to be”. Quote PA34 (first-time mother 15)—Recovery after pregnancy: “I really do want to go back to exercising but I’m not allowed to do anything at all, I’m only allowed to swim and walk and that’s what I do”. |

| Categories of Interpersonal Level | Quotes during Pregnancy | Quotes during the Postpartum Period |

|---|---|---|

| Social influence | Quote PA35 (pregnant woman 11)—imposed physical restrictions: “I have to repeat to myself ’No, you can’t go for a run any longer‘. Even though I would still be able to do it, it is not recommended anymore”. Quote PA36 (pregnant woman 4): Social discouragement: “Those comments made me stop riding my race bike earlier than I had planned. My race bike was standing in the hallway of our office, and my colleagues were saying to each other, ’Is she still cycling, that is not acceptable.’ So that may also be a factor, for me that was the reason that made me stop doing it”. Quote PA37 (pregnant woman 1)—professional support: “I try to keep moving as much as possible. Also, my gynecologist is in favor of this. She said that if I keep moving, it might help me to have a smooth delivery”. Quote PA38 (expecting father 8)—influence of wife: “At the beginning, especially when she felt nauseous, I was worried to leave her alone and had difficulties to say ‘ok so now I will go exercise’”. Quote SB7 (expecting father 11)—partner support and influence of wife: “I did much more in the household at the end of her pregnancy (…) She had pain when cleaning the dishes, so I told her not to do it anymore. I had to stand up much more, to take this or that. But at the beginning of her pregnancy, we were lying down often on the sofa much more. Because she was constantly tired, and then I just went and laid down with her”. | Quote PA39 (first-time mother 13): “I would very much like to do something, but my husband is self-employed, so he gets home quite late. Then he also has his sport activities planned, soccer, tennis,... This means that I don’t have much time to do anything myself”. |

| Influence of baby | Quote PA40 (first-time father 16)—role model: “You feel like you have to be a role model”. Quote PA41 (first-time father 2)—practical constraints: “It is a lot of organization, for example the climbing club, you have to keep him [the baby] busy once you are there, so it is because of laziness that you stay at home and just do something else. And not to have all the hassle that comes with it”. Quote SB8 (first time mother 3)—feeding child: “At the beginning you had to sit still to feed the baby, and that means sitting still for a long time”. |

| Categories and Subcategories of Environmental Level | Quotes during Pregnancy | Quotes during the Postpartum Period |

|---|---|---|

| Meso/Macro | ||

| Environment constraints | Quote PA42 (pregnant woman 10): “There are not many options for pregnancy swimming. Here in [name city] you can go to the [name swimming pool], but that is only on Sundays, and that is not a good time for me”. | |

| Meso/Macro | ||

| Product price | Quote PA43 (pregnant woman 1): “I searched for pregnancy yoga, but it was 14€ per lesson, it was mainly the price of this course that prevented me from doing it”. | Quote PA44 (first-time mother 5): “I want to engage in sports activities, but I do not want to spend money on a babysitter for that”. |

| Categories and Subcategories of Policy Level | Quotes during Pregnancy | Quotes during the Postpartum Period |

|---|---|---|

| Governmental regulations | ||

| Maternity leave regulations | Quote SB9 (pregnant woman 13): “I have been home since December, I had to quit my job immediately as I am a childcare worker. It is a job during which I stand a lot, I am very busy during the day. But now, if I don’t feel like doing some household work, I sit down on the sofa and watch a film or a series”. | Quote PA45 (first-time mother 14): “I work in a healthcare setting, for me, being at work was mostly my exercise. You hardly sit down and you have to walk around a lot. Physical work as well, lifting up things. (…) I will start working again in a month, and then I think moving more will come back”. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Versele, V.; Stok, F.M.; Dieberger, A.; Deliens, T.; Aerenhouts, D.; Deforche, B.; Bogaerts, A.; Devlieger, R.; Clarys, P. Determinants of Changes in Women’s and Men’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior across the Transition to Parenthood: A Focus Group Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042421

Versele V, Stok FM, Dieberger A, Deliens T, Aerenhouts D, Deforche B, Bogaerts A, Devlieger R, Clarys P. Determinants of Changes in Women’s and Men’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior across the Transition to Parenthood: A Focus Group Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042421

Chicago/Turabian StyleVersele, Vickà, Femke Marijn Stok, Anna Dieberger, Tom Deliens, Dirk Aerenhouts, Benedicte Deforche, Annick Bogaerts, Roland Devlieger, and Peter Clarys. 2022. "Determinants of Changes in Women’s and Men’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior across the Transition to Parenthood: A Focus Group Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042421

APA StyleVersele, V., Stok, F. M., Dieberger, A., Deliens, T., Aerenhouts, D., Deforche, B., Bogaerts, A., Devlieger, R., & Clarys, P. (2022). Determinants of Changes in Women’s and Men’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior across the Transition to Parenthood: A Focus Group Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042421