Development and Poverty Dynamics in Severe Mental Illness: A Modified Capability Approach in the Chinese Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

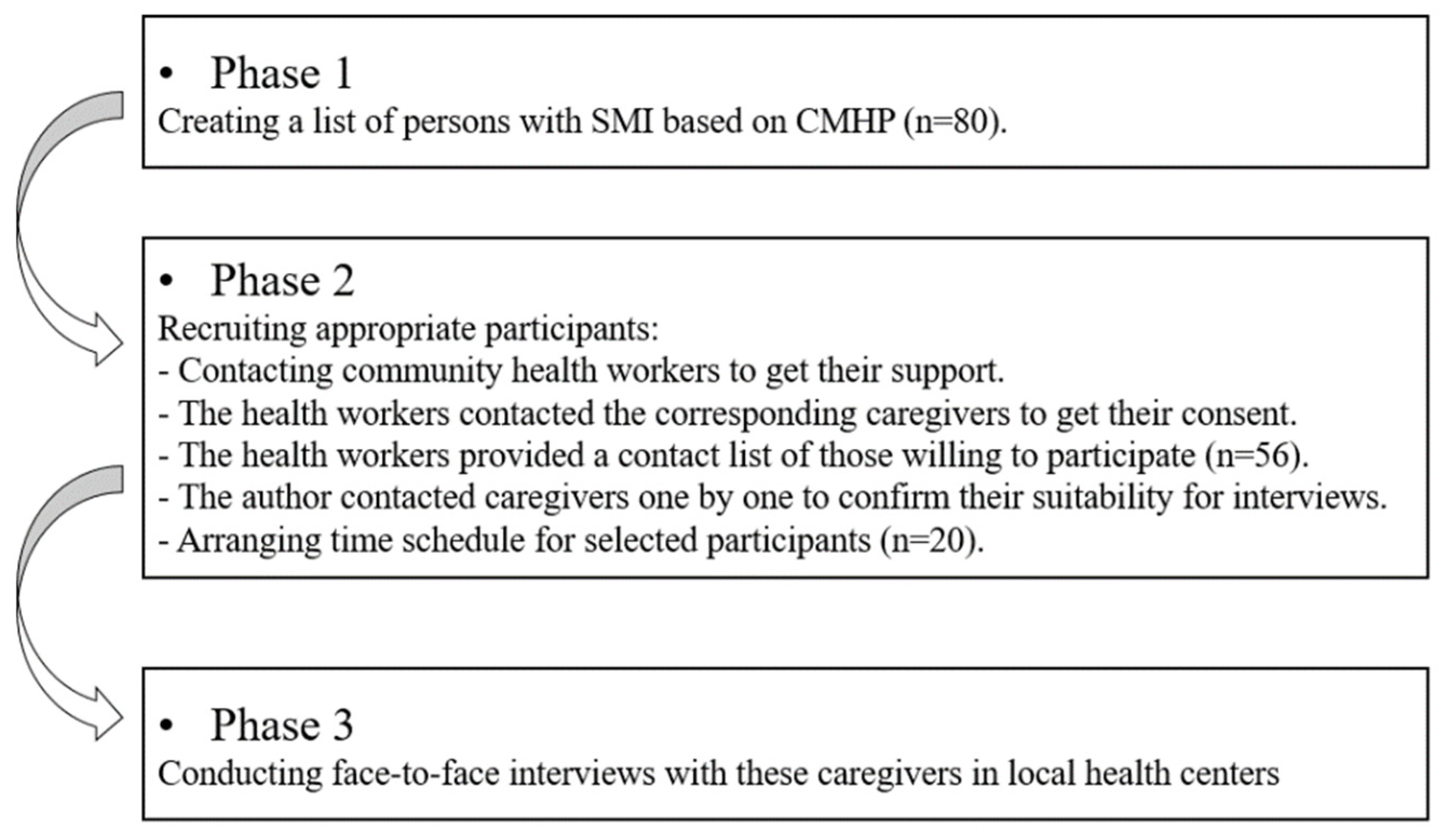

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Perceived Development and Changes

Contracting land out not only reduced manual work, but also made me feel safe. Agricultural incomes can be greatly affected by the climate. Now, regardless of the climate, the income is more stable. That is the best part of becoming a city dweller. (No. 3).

After our farmlands were claimed, every month I can receive around three thousand CNY. For a family like ours, this was the biggest revenue. Without it, I cannot image how hard our life could have been. (No. 16)

Those opportunities are for others, not for us. No matter how much others have earned, that’s their fates. I have a wife with schizophrenia. I must stay at home to provide care. Poverty is my fate. (No. 8)

3.2. Long-Term Impacts of SMI on Poverty

I never bring friends home. This is a fatal blow to my business. Others cannot trust me without knowing my family. If they knew, I would also lose their trust. My brother is much richer than me. He can take his business partners home; they drink together and achieve consensus on cooperation in everyday interactions. I cannot. (No. 19)

We had richer relatives. I gave them gifts and was rejected. They despised me. They were afraid that I may ask them for help. I kept myself away from neighbors. Every time I visited them, I felt depressed to see them being better off. I had no social network. (No. 5)

Mental illness may affect at least three generations. The illness on my mother affected her generation, mine and my kids’. When I was young, only my father worked to support the whole family. We lived in poverty and I dropped out from school early. As a result, I was not capable to find a well-paid job. I cannot work far away because I need to keep an eye on her. The current situation will inevitably affect my children. (No. 7)

3.3. Complex Roles of Social Protection

My wife can hardly do any work. She was only rated as third-level disability and was not qualified for subsidies. I complained, the reason given was that she showed no obvious signs of disability. I think it’s not fair. My neighbor got a grant. He had his left hand amputated but he could do many things as usual. (No. 4)

I live worse than ten years ago. It gets harder to find a part-time job as I grow older. Meanwhile, the medical expenditure for both my wife and me are higher. My children are still young, sometimes I need to support them. I borrowed money to pay for the insurance. Now I am heavily in debt. (No. 8)

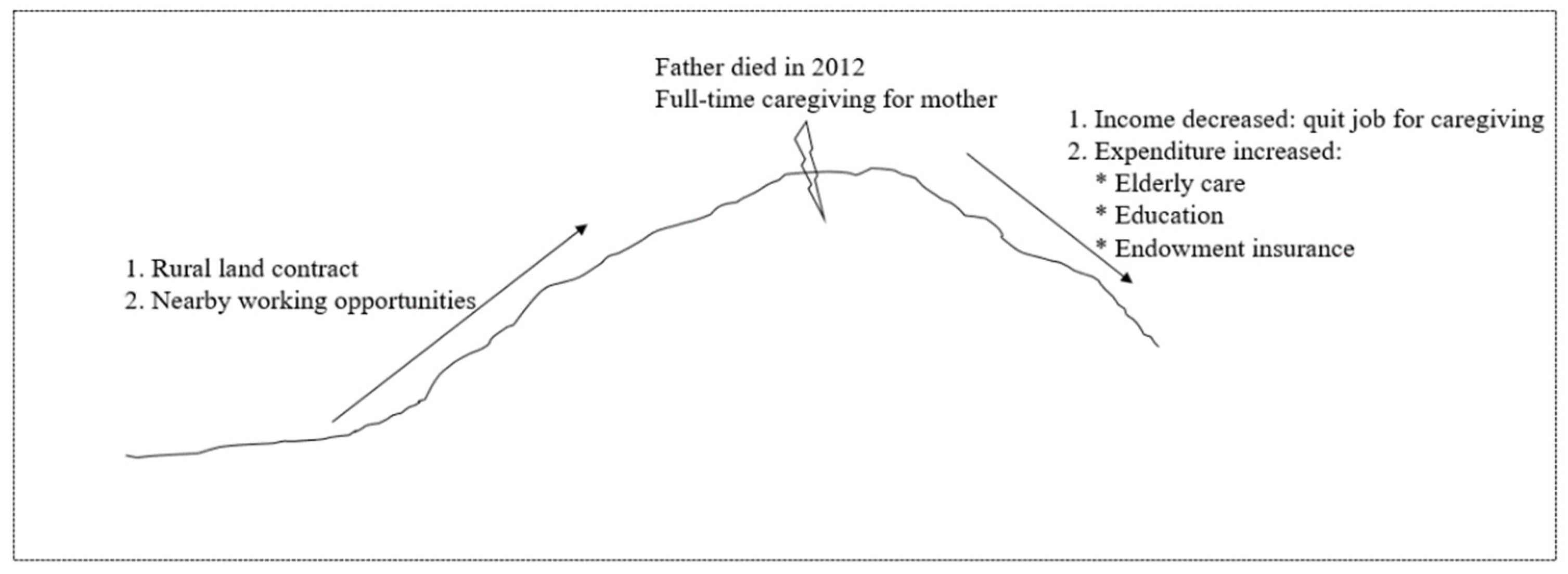

3.4. Presenting the Full Picture: Two Case Illustration

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iniguez-Montiel, A.J. Growth with equity for the development of Mexico: Poverty, inequality, and economic growth (1992–2008). World Dev. 2014, 59, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dercon, S.; Hoddinott, J.; Woldehanna, T. Growth and chronic poverty: Evidence from rural communities in Ethiopia. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 48, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Baulch, B. Parallel realities: Exploring poverty dynamics using mixed methods in rural Bangladesh. J. Dev. Stud. 2011, 47, 118–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Staveren, I.; Webbink, E.; de Haan, A.; Foa, R. The last mile in analyzing wellbeing and poverty: Indices of social development. Forum Soc. Econ. 2014, 43, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aghion, P.; Bolton, P. A theory of trickle-down growth and development. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1997, 64, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, N.M. Growth, employment and poverty in South Africa: In search of a trickle-down effect. J. Income Distrib. 2011, 20, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinci, M. Inequality and economic growth: Trickle-down effect revisited. Dev. Policy Rev. 2018, 36, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-H.; Luo, W.; He, M.-X.; Yang, X.; Liu, B.; Guo, Y.; Thornicroft, G.; Chan, C.L.W.; Ran, M.-S. Household poverty in people with severe mental illness in rural China 1994–2015. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Bai, X.M. Measurement and decomposition of China’s urban and rural household poverty vulnerability: An empirical study based on CHNS. Quant. Econ. Tech. Econ. Res. 2010, 27, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Buch-Hansen, M. Goodbye to universal development and call for diversified, democratic sufficiency and frugality. The need to re-conceptualising development and revitalising development studies. Forum Dev. Studies 2012, 39, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Combating poverty in development: A summary and evaluation of China’s mass poverty reduction in past 30 years. Manag. World 2008, 11, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 52, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Feng, X.; Wang, S.; Qiu, H. China’s poverty alleviation over the last 40 years: Successes and challenges. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2020, 64, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. Market economy and China’s “common prosperity” campaign. J. Chin. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. The economic lives of the poor. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion, M. Poverty Comparisons; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, M.; Weng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yu, Y.; Peng, M.; Luo, W.; Hu, S.; Yang, X.; Liu, B.; et al. Change of treatment status of persons with severe mental illness in a rural China, 1994–2015. BJPsychiatry Open 2019, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, D.F.K.; Li, J.C.M. Cultural influence on Shanghai Chinese people’s help-seeking for mental health problems: Implications for social work practice. Br. J. Soc. Work 2012, 44, 868–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-H.; Luo, W.; Liu, B.; Kuang, W.-H.; Davidson, L.; Chan, C.L.W.; Lu, L.; Xiang, M.-Z.; Ran, M.-S. Poverty transitions in severe mental illness: Longitudinal analysis of social drift in China, 1994–2015. Psychol. Med. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, G.; Hauser, M.; De Hert, M.; Lacluyse, K.; Wampers, M.; Correll, C.U. Personal stigma in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A systematic review of prevalence rates, correlates, impact and interventions. World Psychiatry 2013, 12, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.-S.; Zhang, T.-M.; Wong, I.Y.-L.; Yang, X.; Liu, C.-C.; Liu, B.; Luo, W.; Kuang, W.-H.; Thornicroft, G.; Chan, C.; et al. Internalized stigma in people with severe mental illness in rural China. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.A.; Liu, J.J. Constructing social security and social welfare for different groups (panel): Living context of rural mental disabled persons and policy recommendation. Heilongjiang Acad. Soc. Sci. 2015, 5, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V.; Araya, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Chisholm, D.; Cohen, A.; De Silva, M.; Hosman, C.; McGuire, H.; Rojas, G.; van Ommeren, M. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2007, 370, 991–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Capability and well-being73. Qual. Life 1993, 30, 270–293. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Well-being, agency and freedom: The Dewey lectures 1984. J. Philos. 1985, 82, 169–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbow, S.; Rudnick, A.; Forchuk, C.; Edwards, B. Using a capabilities approach to understand poverty and social exclusion of psychiatric survivors. Disabil. Soc. 2014, 29, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-Y. Psychiatry and mental health in post-reform China. In Mental Health in China and the Chinese Diaspora: Historical and Cultural Perspectives; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.; Wolf, A.; Wang, X. Experienced stigma and self-stigma in Chinese patients with schizophrenia. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013, 35, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-H.; Peng, M.-M.; Bai, X.; Luo, W.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Thornicroft, G.; Chan, C.L.W.; Ran, M.-S. Schizophrenia, social support, caregiving burden and household poverty in rural China. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremin, P.; Nakabugo, M.G. Education, development and poverty reduction: A literature critique. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2012, 32, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songsore, J. The urban transition in Ghana: Urbanization, national development and poverty reduction. Ghana Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 17, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Pansera, M.; Martinez, F. Innovation for development and poverty reduction: An integrative literature review. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, F.J.; Baxter, A.J.; Cheng, H.; Shidhaye, R.; Whiteford, H. The burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in China and India: A systematic analysis of community representative epidemiological studies. Lancet 2016, 388, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y. Land consolidation boosting poverty alleviation in China: Theory and practice. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groce, N.; Kett, M.; Lang, R.; Trani, J.-F. Disability and poverty: The need for a more nuanced understanding of implications for development policy and practice. Third World Q. 2011, 32, 1493–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Pellissery, S. Giants old and new: Promoting social security and economic growth in the Asia and Pacific region. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2008, 61, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhai, F. Anti-Poverty Family Policies in China: A Critical Evaluation. Asian Soc. Work. Policy Rev. 2012, 6, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Ye, T.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, J. Financial protection effects of modification of China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme on rural households with chronic diseases. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, B.; Xu, Y. Mechnism of domestic expenditure poverty and its governance from the perspective of capability: Based on social survey in four counties of Hubei Province. Soc. Secur. Res. 2020, 21, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.H.; Kleinman, A. ‘Face’ and the embodiment of stigma in China: The cases of schizophrenia and AIDS. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.-Y.; van Riper, M. Research on caregiving in Chinese families living with mental illness: A critical review. J. Fam. Nurs. 2010, 16, 68–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Deng, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, Q.; Lai, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Shen, W. Cross-sectional survey of the relationship of symptomatology, disability and family burden among patients with schizophrenia in Sichuan, China. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Anakwenze, U.; Zuberi, D. Mental health and poverty in the inner city. Health Soc. Work. 2013, 38, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimberlin, S.; Berrick, J.D. Poor for how long? Chronic versus transient child poverty in the United States. In Theoretical and Empirical Insights into Child and Family Poverty; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Jiang, L.; Li, C.; Sun, M.; Rieger, A.; Hao, M. How to deal with burden of critical illness: A comparison of strategies in different areas of China. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 30, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Xiao, S.; Chen, H.; Hanna, F.; Jotheeswaran, A.T.; Luo, D.; Parikh, R.; Sharma, E.; Usmani, S.; Yu, Y.; et al. The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet 2016, 388, 3074–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Needs and supply of social security for people with mental disability: Current situation, problems and policy suggestions. Disabl. Res. 2020, 1, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, C.G. Socioeconomic status and mental illness: Tests of the social causation and selection hypotheses. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2005, 75, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Caregiver Information N(%); M(SD) | Information of Persons with SMI N(%); M(SD) | Household Information N(%); M(SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58.15 (11.65) | 58.85 (11.40) | |

| Gender, Female | 8 (40%) | 13 (65%) | |

| Employment | |||

| Unemployed & retired | 4 (20%) | 13 (65%) | |

| Part-time work | 9 (45%) | 2 (10%) | |

| Farmer | 7 (35%) | 5 (25%) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Have a spouse | 18 (90%) | 14 (70%) | |

| Have no spouse | 2 (10%) | 6 (30%) | |

| Relations to persons with SMI | |||

| Parents | 2 (10%) | ||

| Spouse | 13 (65%) | ||

| Sons and daughter | 3 (65%) | ||

| Siblings | 2 (10%) | ||

| Household income per capita in 2018 (CNY) | 28,620 (6676.36) | ||

| Household size in 2018 | 3.05 (1.10) | ||

| Poverty typology | |||

| Persistent poverty | 6 (30%) | ||

| Fell into poverty | 6 (30%) | ||

| Escaped poverty | 3 (15%) | ||

| Never experienced poverty | 5 (25%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Y.-H.; Peng, M.-M. Development and Poverty Dynamics in Severe Mental Illness: A Modified Capability Approach in the Chinese Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042351

Yu Y-H, Peng M-M. Development and Poverty Dynamics in Severe Mental Illness: A Modified Capability Approach in the Chinese Context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042351

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Yue-Hui, and Man-Man Peng. 2022. "Development and Poverty Dynamics in Severe Mental Illness: A Modified Capability Approach in the Chinese Context" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042351

APA StyleYu, Y.-H., & Peng, M.-M. (2022). Development and Poverty Dynamics in Severe Mental Illness: A Modified Capability Approach in the Chinese Context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042351