Personal Characteristics for Successful Senior Cohousing: A Proposed Theoretical Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. Senior Cohousing: Entrepreneurship Challenges and Barriers

- Empirical studies and publications by residents of cohousing developments themselves;

- Research focusing on demographic change and the evolving social model, with the shift away from traditional family structures, in the quest for well-being based on independent and autonomous aging;

- Studies looking at architectural design and how it contributes to social interaction;

- Research focusing on neighborhoods and sustainable urban development;

- Emerging topics concerning the legal and financial aspects of cohousing.

2.2. Characterization of the Senior Cohousing Entrepreneurs

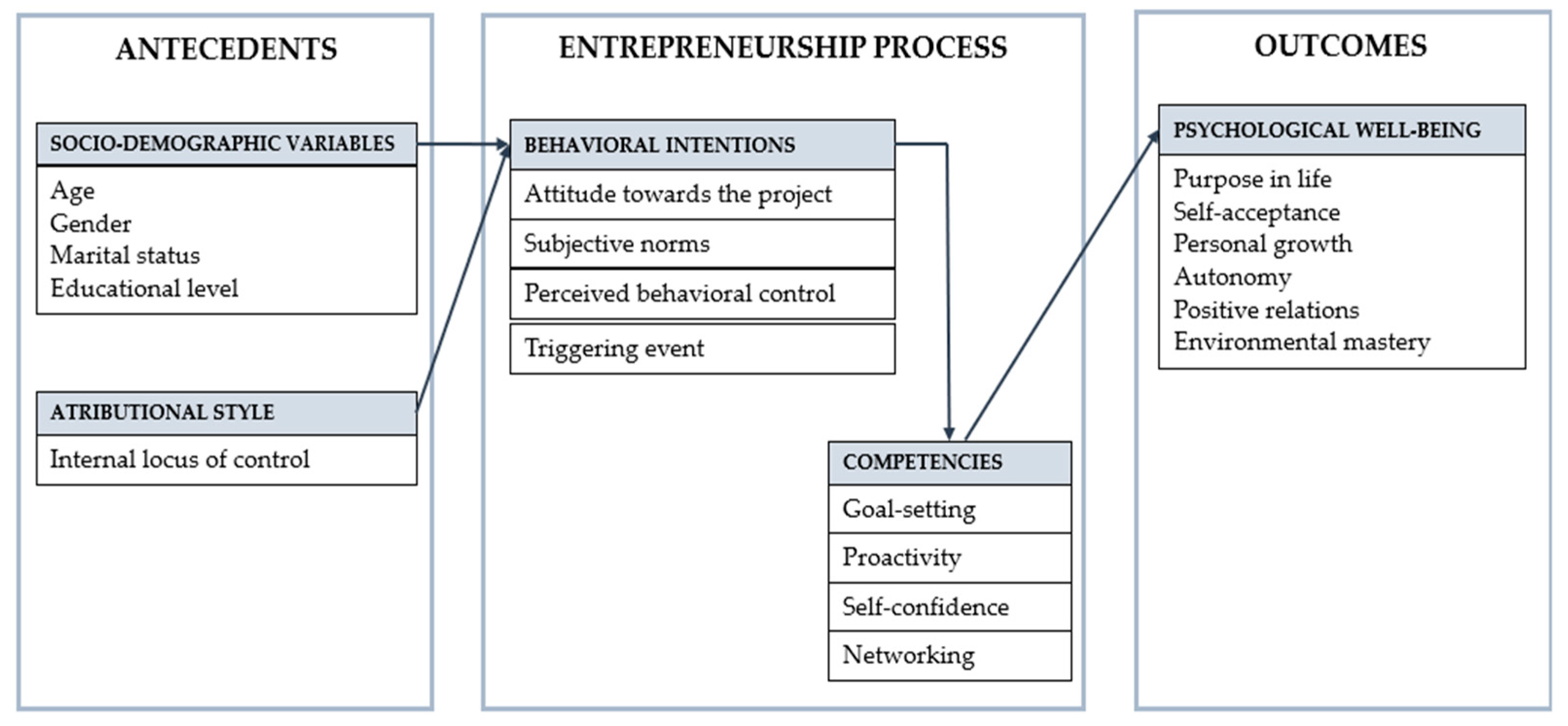

3. Integrated Theoretical Model: Entrepreneurship and Well-Being in Senior Cohousing

3.1. Antecedents: Socio-Demographic Variables and Attributional Style

3.2. Entrepreneurship Process: Behavioral Intentions and Competencies

3.3. Outcomes: Psychological Well-Being

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Directions

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lardiés Bosque, R. A Qualitative Study of the Effects of Residential Mobility on the Quality of Life Among the Elderly. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2008, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, J.; Lopez, J.; Díaz, M.P.; Alemán, C.; Trinidad, A.; Castón, P. La Soledad En Las Personas Mayores: Influencias Personales, Familiares y Sociales: Análisis Cualitativo; Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales: Madrid, Spain, 2001; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Brenton, M. Senior Cohousing Communities: An Alternative Approach for the UK? Joseph Rowntree Foundation: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Del Monte, J. Cohousing: Modelo Residencial Colaborativo y Capacitante Para un Envejecimiento Feliz; Fundación Pilares: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, M. Spatial Agency: Creating New Opportunities for Sharing and Collaboration in Older People’s Cohousing. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arkebauer, J. Golden Entrepreneuring. Mature Person’s Guide to Starting a Successful Business; McGraw-Hill Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, S.L.; Conway Dato-on, M. A Cross Cultural Study of Gender-Role Orientation and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, E.; Junquera, B. Factores Determinantes En La Creación de Pequeñas Empresas: Una Revisión de La Literatura. Pap. De Econ. Española 2001, 89/90, 322–342. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Let’s Put the Person Back into Entrepreneurship Research: A Meta-Analysis on the Relationship between Business Owners’ Personality Traits, Business Creation, and Success. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 16, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship; Kent, C., Sexton, D., Vesper, K., Eds.; Englewood Cliffs: Bergen County, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F.; Brazeal, D.V. Entrepreneurial Potential and Potential Entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D. Human Motivation; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomksky, S.; Sheldon, K.M.; Schkade, D. Pursuing Happiness: The Architecture of Sustainable Change. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2005, 9, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryff, C.D. Beyond Ponce de Leon and Life Satisfaction: New Directions in Quest of Successful Ageing. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1989, 12, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCamant, K.; Durrett, C.R. Cohousing: A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bamford, G. Cohousing for Older People: Housing Innovation in the Netherlands and Denmark. Australas. J. Ageing 2005, 24, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rusinovic, K.; van Bochove, M.; van de Sande, J. Senior Co-Housing in the Netherlands: Benefits and Drawbacks for Its Residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durrett, C. The Senior Cohousing Handbook; New Society Publishers: Gabriola, BC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.S. Evaluation of Community Planning and Life of Senior Cohousing Projects in Northern European Countries. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2004, 12, 1189–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, A.P. Elder Co-Housing in the United States: Three Case Studies. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labit, A. Self-Managed Co-Housing in the Context of an Ageing Population in Europe. Urban Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestbro, D.U. From Collective Housing to Cohousing—A Summary of Research. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2000, 17, 164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, A.P. Sense of Community, Loneliness, and Satisfaction in Five Elder Cohousing Neighborhoods. J. Women Aging 2020, 32, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tummers, L. The Re-Emergence of Self-Managed Co-Housing in Europe: A Critical Review of Co-Housing Research. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 2023–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, R.H.W.; Leland, S. Cohousing for Whom? Survey Evidence to Support the Diffusion of Socially and Spatially Integrated Housing in the United States. Hous. Policy Debate 2018, 28, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L. Self-managed co-housing: Assessing urban qualities and bottlenecks in the planning system. In Making Room for People: Choice, Voice and Liveability in Residential Areas; Qu, L., Hasselaar, L., Eds.; Techne Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scanlon, K.; Fernández Arrigoitia, M. Development of New Cohousing: Lessons from a London Scheme for the over-50s. Urban Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fenster, M. Community by Covenant, Process, and Design: Cohousing and the Contemporary Common Interest Community. J. Land Use Environ. Law 2018, 15, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Etxezarreta, A.; Cano, G.; Merino, S. Las cooperativas de viviendas de cesion de uso: Experiencias emergentes en España. In CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa; University of Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, J.E.; Devesa, M.; Meneu, R.; Alonso, J.J.; Encinas, B.; Escribano, F.; Moya, P.; Pardo, I.; del Pozo, R. La Revolución de La Longevidad y Su Influencia en Las Necesidades de Financiación de Los Mayores; Fundación Edad & Vida. VidaCaixa: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, H. Saving Space, Sharing Time: Integrated Infrastructures of Daily Life in Cohousing. Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Succesful Aging. Gerontologist 1997, 37, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, P.; Sanders, J.; Maussen, S.; Kemperman, A. Collective Self-Build for Senior Friendly Communities. Studying the Effects on Social Cohesion, Social Satisfaction and Loneliness. Hous. Stud. 2021, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killock, J. Is Cohousing a Suitable Housing Typology for an Ageing Population within the UK? Royal Institute of British Architects: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, S.A.; Locke, E.A. Direct and Indirect Effects of Three Core Charismatic Leadership Components on Performance and Attitudes. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. New Developments in Goal Setting and Task Performance; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B. Entrepreneurial Behavior; Scott Foresman & Company: Northbrook, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, G.N.; Jansen, E. The Founder’s Self-Assessed Competence and Venture Performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1992, 7, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo, I.; Irigoyen, J.M. Entrepreneurship in the EU: To Wish and Not to Be. Small Bus. Econ. 2006, 26, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechavarria, D.M.; Reynolds, P.D. Cultural Norms & Business Start-Ups: The Impact of National Values on Opportunity and Necessity Entrepreneurs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2009, 5, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardíes Bosque, R.; Rojo Pérez, F.; Fernández Mayoralas, G.; Forjaz, M.J.; Martínez Marín, P. Cambios residenciales y calidad de vida de los adultos-mayores en España. In Población y Espacios Urbanos; Pujadas Rúbies, I., Bayona Carrasco, J., García Coll, A., Gil Alonso, F., López Villa Nueva, C., Sánchez Aguilera, D., Vidal Bendito, T., Eds.; Universidad de La Rioja: La Rioja, Spain, 2011; pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, P.; Honig, B. The Role of Social and Human Capital among Nascent Entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized Expectancies for Internal versus External Control of Reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oros, L. Locus de Control: Evolución de Su Concepto y Operacionalización. Rev. Psicol. 2005, 14, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F. Intention-Based Models of Entrepreneurship Education. Small Bus. 2004, 2004, 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, T.J.; Ellen, P.S.; Ajzen, I. A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Born to be an entrepreneur? Revisiting the personality approach to entrepreneurship. In The Psychology of Entrepreneurship; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, T.M.; Boyd, D.P. Psychological Characteristics Associated with Performence in Entrepreneurial Firms and Smaller Businesses. J. Bus. Ventur. 1987, 2, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veciana, J.M. La Creación de Empresas. Un Enfoque Gerencial; La Caixa: Valencia, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ruth, J.E.; Birren, J.E. Creativity in Adulthood and Old Age: Relations to Intelligence, Sex and Mode of Testing. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1985, 8, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipple, S. Self-Employment in the United States: An Update. Mon. Labor Rev. 2004, 127, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana García, C. Dimensiones Del Éxito de Las Empresas Emprendedoras. Investig. Eur. Dir. Y Econ. Empresa 2001, 7, 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Filion, L.J. Emprendedores y Propietarios-Dirigentes de Pequeña y Mediana Empresa (PME). Adm. Y Organ. 2003, 10, 113–152. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C.; Atkinson, J.W.; Clark, R.A.; Lowell, E.L. The Achievement Motive; Irvington Publishers: North Stratford, NH, USA, 1976; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E.A. Toward a Theory of Task Motivation and Incentives. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1968, 3, 157–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, G.P.; Locke, E.A. New Developments in and Directions for Goal-Setting Research. Eur. Psychol. 2007, 12, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durán Aponte, E. Distinción Entre Actitud Emprendedora y Autoeficacia: Validez y Confiabilidad En Estudiantes Universitarios; Educación y Futuro Digital: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kirzner, I.M. Creativity and/or Alertness: A Reconsideration of the Schumpeterian Entrepreneur. Rev. Austrian Econ. 1999, 11, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.R.; Locke, E.A. The Relationship of Entrepreneurial Traits, Skill, and Motivation to Subsequent Venture Growth. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schott, T.; Sedaghat, M. Innovation Embedded in Entrepreneurs’ Networks and National Educational Systems. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 43, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuentelsaz, L.; Montero, J. ¿Qué Hace Que Algunos Emprendedores Sean Más Innovadores? Universia Bus. Rev. 2015, 2015, 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P. The Varieties of Wellbeing. Exp. Aging Res. 1983, 9, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Molero, F.; Silván-Ferrero, P.; García-Ael, C.; Fernández, I.; Tecglen, C. La Relación Entre La Discriminación Percibida y El Balance Afectivo En Personas Con Discapacidad Física: El Papel Mediador Del Dominio Del Entorno. Acta Colomb. Psicol. 2013, 16, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. A Social Cognitive Perspective on Positive Psychology. Rev. Psicol. Soc. 2011, 26, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.S.; White, R.J. The Emotional Intelligence of Entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2007, 20, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Best News yet on the Six-Factor Model of Well-Being. Soc. Sci. Res. 2006, 35, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M.; Shmotkin, D.; Ryff, C.D. Optimizing Well-Being: The Empirical Encounter of Two Traditions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha García, A.C. Bienestar Psicológico Subjetivo y Personas Mayores Residentes. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2014, 25, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Barrio, É.; Castejón, P.; Sancho Castiello, M.; Tortosa, M.Á.; Sundström, G.; Malmberg, B. La Soledad de Las Personas Mayores En España y Suecia: Contexto y Cultura. Rev. Española Geriatría Y Gerontol. 2010, 45, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López Doblas, J.; Díaz Conde, M.D.P. El Sentimiento de Soledad En La Vejez. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2018, 76, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cloutier-Fisher, D.; Kobayashi, K.; Smith, A. The Subjective Dimension of Social Isolation: A Qualitative Investigation of Older Adults’ Experiences in Small Social Support Networks. J. Aging Stud. 2011, 25, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigoitia, M.F.; West, K. Interdependence, Commitment, Learning and Love: The Case of the United Kingdom’s First Older Women’s Co-Housing Community. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 1673–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giorgi, E.; Martín López, L.; Garnica-Monroy, R.; Krstikj, A.; Cobreros, C.; Montoya, M.A. Co-Housing Response to Social Isolation of Covid-19 Outbreak, with a Focus on Gender Implications. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.; Scanlon, K.; Udagawa, C.; Arrigoitia, M.F.; Ferreri, M.; West, K. ‘A Slow Build-Up of a History of Kindness’: Exploring the Potential of Community-Led Housing in Alleviating Loneliness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monton, P.; Reyes, L.-E.; Alcover, C.-M. Personal Characteristics for Successful Senior Cohousing: A Proposed Theoretical Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042241

Monton P, Reyes L-E, Alcover C-M. Personal Characteristics for Successful Senior Cohousing: A Proposed Theoretical Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042241

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonton, Pilar, Luisa-Eugenia Reyes, and Carlos-María Alcover. 2022. "Personal Characteristics for Successful Senior Cohousing: A Proposed Theoretical Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042241

APA StyleMonton, P., Reyes, L.-E., & Alcover, C.-M. (2022). Personal Characteristics for Successful Senior Cohousing: A Proposed Theoretical Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042241