Long-Term Safety of Prenatal and Neonatal Exposure to Paracetamol: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

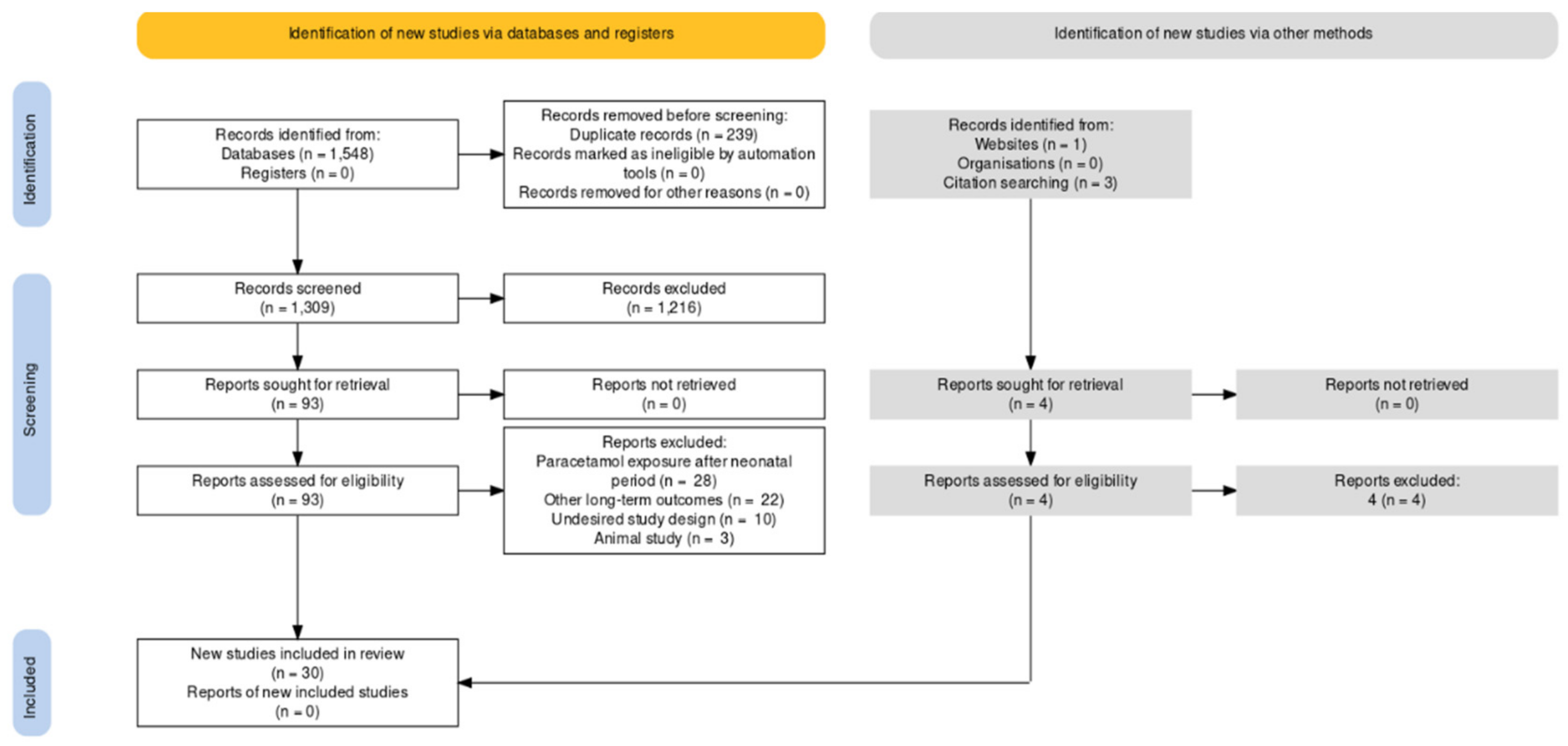

2.4. Study Selection Process and Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment and Assessment of Evidence Certainty

2.6. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Prenatal Exposure

3.2.1. Neurodevelopmental Adverse Outcomes

3.2.2. Atopic Adverse Outcomes

3.2.3. Reproductive Adverse Outcomes

3.3. Neonatal Outcomes

Neurodevelopmental and Atopic Adverse Outcomes

3.4. Risk-of-Bias Assessment and Assessment of Evidence Certainty

3.4.1. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

3.4.2. Assessment of Evidence Certainty

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Comparison with Other Research

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schilling, A.; Corey, R.; Leonard, M.; Eghtesad, B. Acetaminophen: Old drug, new warnings. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2010, 77, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.J. Acetaminophen and the Developing Lung: Could There Be Lifelong Consequences? J. Pediatr. 2021, 235, 264–276.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegaert, K. A Critical Review on the Relevance of Paracetamol for Procedural Pain Management in Neonates. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van den Bosch, G.E.; Dijk, M.V.; Tibboel, D.; de Graaff, J.C. Long-term Effects of Early Exposure to Stress, Pain, Opioids and Anaesthetics on Pain Sensitivity and Neurocognition. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 5879–5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, S.; Florez, I.D.; Tamayo, M.E.; Mbuagbaw, L.; Vanniyasingam, T.; Veroniki, A.A.; Zea, A.M.; Zhang, Y.; Sadeghirad, B.; Thabane, L. Association of Placebo, Indomethacin, Ibuprofen, and Acetaminophen with Closure of Hemodynamically Significant Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2018, 319, 1221–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Anker, J.N.; Allegaert, K. Acetaminophen in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Shotgun Approach or Silver Bullet. J. Pediatr. 2018, 198, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bardanzellu, F.; Neroni, P.; Dessì, A.; Fanos, V. Paracetamol in Patent Ductus Arteriosus Treatment: Efficacious and Safe? Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1438038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, S.W.; Marcotegui, A.R.; Fortwängler, E.; Ditrich, J.; Perazzo, J.C.; Muñoz, E.; de Oliveira, A.C.P.; Fiebich, B.L. AM404, paracetamol metabolite, prevents prostaglandin synthesis in activated microglia by inhibiting COX activity. J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Przybyła, G.W.; Szychowski, K.A.; Gmiński, J. Paracetamol—An old drug with new mechanisms of action. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol 2020. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, H.; Stewart, A.; Mitchell, E.; Crane, J.; Eyers, S.; Weatherall, M.; Beasley, R. The role of paracetamol in the pathogenesis of asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2010, 40, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegaert, K.; Van Den Anker, J. How to translate neuro-cognitive and behavioural outcome data in animals exposed to paracetamol to the human perinatal setting? Arch. Med. Sci. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ionnidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies that Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Samiee-Zafarghandy, S.; Sushko, K.; Van Den Anker, J. Long-Term Safety of Prenatal and Neonatal Exposure to Paracetamol: A Protocol for a Systematic Review. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2020, 4, e000907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2013. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Dufault, B.; Klar, N. The quality of modern cross-sectional ecologic studies: A bibliometric review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betran, A.P.; Torloni, M.R.; Zhang, J.; Ye, J.; Mikolajczyk, R.; Deneux-Tharaux, C.; Oladapo, O.T.; Souza, J.P.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Vogel, J.P. What is the optimal rate of caesarean section at population level? A systematic review of ecologic studies. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cortes-Ramirez, J.; Naish, S.; Sly, P.D.; Jagals, P. Mortality and morbidity in populations in the vicinity of coal mining: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Granholm, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Møller, M.H. Use of the GRADE approach in systematic reviews and guidelines. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.H.; Mustafa, R.A.; Schünemann, H.J.; Sultan, S.; Santesso, N. Rating the certainty in evidence in the absence of a single estimate of effect. Evid. Based Med. 2017, 22, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bauer, A.Z.; Kriebel, D. Prenatal and perinatal analgesic exposure and autism: An ecological link. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stergiakouli, E.; Thapar, A.; Davey Smith, G. Association of Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy with Behavioral Problems in Childhood: Evidence Against Confounding. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 964–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertoldi, A.D.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Boing, A.C.; da Silva Dal Pizzol, T.; Miranda, V.I.A.; Silveira, M.P.T.; Freitas Silveira, M.; Domingues, M.R.; Santos, I.S.; Bassani, D.G.; et al. Associations of acetaminophen use during pregnancy and the first year of life with neurodevelopment in early childhood. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2020, 34, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Riley, A.W.; Lee, L.C.; Hong, X.; Wang, G.; Tsai, H.J.; Mueller, N.T.; Pearson, C.; Thermitus, J.; Panjwani, A.; et al. Maternal Biomarkers of Acetaminophen Use and Offspring Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ji, Y.; Azuine, R.E.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, W.; Hong, X.; Wang, G.; Riley, A.; Pearson, C.; Zuckerman, B.; Wang, X. Association of Cord Plasma Biomarkers of In Utero Acetaminophen Exposure with Risk of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Childhood. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golding, J.; Gregory, S.; Clark, R.; Ellis, G.; Iles-Caven, Y.; Northstone, K. Associations between paracetamol (acetaminophen) intake between 18 and 32 weeks gestation and neurocognitive outcomes in the child: A longitudinal cohort study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2020, 34, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlenterie, R.; Wood, M.E.; Brandlistuen, R.E.; Roeleveld, N.; van Gelder, M.M.; Nordeng, H. Neurodevelopmental problems at 18 months among children exposed to paracetamol in utero: A propensity score matched cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1998–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ystrom, E.; Gustavson, K.; Brandlistuen, R.E.; Knudsen, G.P.; Magnus, P.; Susser, E.; Davey Smith, G.; Stoltenberg, C.; Surén, P.; Håberg, S.E.; et al. Prenatal Exposure to Acetaminophen and Risk of ADHD. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20163840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liew, Z.; Bach, C.C.; Asarnow, R.F.; Ritz, B.; Olsen, J. Paracetamol use during pregnancy and attention and executive function in offspring at age 5 years. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Cardenas, A.; Hivert, M.F.; Tiemeier, H.; Bertoldi, A.D.; Oken, E. Associations of prenatal or infant exposure to acetaminophen or ibuprofen with mid-childhood executive function and behaviour. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2020, 34, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streissguth, A.P.; Treder, R.P.; Barr, H.M.; Shepard, T.H.; Bleyer, W.A.; Sampson, P.D.; Martin, D.C. Aspirin and acetaminophen use by pregnant women and subsequent child IQ and attention decrements. Teratology 1987, 35, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.M.; Waldie, K.E.; Wall, C.R.; Murphy, R.; Mitchell, E.A.; ABC Study Group. Associations between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and ADHD symptoms measured at ages 7 and 11 years. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Petersen, T.G.; Liew, Z.; Andersen, A.N.; Andersen, G.L.; Andersen, P.K.; Martinussen, T.; Olsen, J.; Rebordosa, C.; Tollånes, M.C.; Uldall, P.; et al. Use of paracetamol, ibuprofen or aspirin in pregnancy and risk of cerebral palsy in the child. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andersen, A.B.; Farkas, D.K.; Mehnert, F.; Ehrenstein, V.; Erichsen, R. Use of prescription paracetamol during pregnancy and risk of asthma in children: A population-based Danish cohort study. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 4, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Marcos, L.; Sanchez-Solis, M.; Perez-Fernandez, V.; Pastor-Vivero, M.D.; Mondejar-Lopez, P.; Valverde-Molina, J. Is the effect of prenatal paracetamol exposure on wheezing in preschool children modified by asthma in the mother? Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2009, 149, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piler, P.; Švancara, J.; Kukla, L.H. Role of combined prenatal and postnatal paracetamol exposure on asthma development: The Czech ELSPAC study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.O.; Newson, R.B.; Sherriff, A.; Henderson, A.J.; Heron, J.E.; Burney, P.G.; Golding, J.; ALSPAC Study Team. Paracetamol use in pregnancy and wheezing in early childhood. Thorax 2002, 57, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jedrychowski, W.; Spengler, J.D.; Maugeri, U.; Miller, R.L.; Budzyn-Mrozek, D.; Perzanowski, M.; Flak, E.; Mroz, E.; Majewska, R.; Kaim, I.; et al. Effect of prenatal exposure to fine particulate matter and intake of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) in pregnancy on eczema occurrence in early childhood. Sci Total Environ. 2011, 409, 5205–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Persky, V.; Piorkowski, J.; Hernandez, E.; Chavez, N.; Wagner-Cassanova, C.; Vergara, C.; Pelzel, D.; Enriquez, R.; Gutierrez, S.; Busso, A. Prenatal exposure to acetaminophen and respiratory symptoms in the first year of life. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008, 101, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rebordosa, C.; Kogevinas, M.; Sørensen, H.T.J. Pre-natal exposure to paracetamol and risk of wheezing and asthma in children: A birth cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 37, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magnus, M.C.; Karlstad, Ø.; Håberg, S.E.; Nafstad, P.; Davey Smith, G.; Nystad, W. Prenatal and infant paracetamol exposure and development of asthma: The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sordillo, J.E.; Scirica, C.V.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Gillman, M.W.; Bunyavanich, S.; Camargo CAJr Weiss, S.T.; Gold, D.R.; Litonjua, A.A. Prenatal and infant exposure to acetaminophen and ibuprofen and the risk for wheeze and asthma in children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bakkeheim, E.; Mowinckel, P.; Carlsen, K.H.; Håland, G.; Carlsen, K.C. Paracetamol in early infancy: The risk of childhood allergy and asthma. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, A.; Brix, N.; Lauridsen, L.L.B.; Olsen, J.; Parner, E.T.; Liew, Z.; Olsen, L.H.; Ramlau-Hansen, C.H. Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) Exposure During Pregnancy and Pubertal Development in Boys and Girls from a Nationwide Puberty Cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, B.G.; Thankamony, A.; Hughes, I.A.; Ong, K.K.; Dunger, D.B.; Acerini, C.L. Prenatal paracetamol exposure is associated with shorter anogenital distance in male infants. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 2642–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lind, D.V.; Main, K.M.; Kyhl, H.B.; Kristensen, D.M.; Toppari, J.; Andersen, H.R.; Andersen, M.S.; Skakkebæk, N.E.; Jensen, T.K. Maternal use of mild analgesics during pregnancy associated with reduced anogenital distance in sons: A cohort study of 1027 mother-child pairs. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snijder, C.A.; Kortenkamp, A.; Steegers, E.A.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Hofman, A.; Hass, U.; Burdorf, A. Intrauterine exposure to mild analgesics during pregnancy and the occurrence of cryptorchidism and hypospadia in the offspring: The Generation R Study. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shaheen, S.O.; Newson, R.B.; Ring, S.M.; Rose-Zerilli, M.J.; Holloway, J.W.; Henderson, A.J. Prenatal and infant acetaminophen exposure, antioxidant gene polymorphisms, and childhood asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oncel, M.Y.; Eras, Z.; Uras, N.; Canpolat, F.E.; Erdeve, O.; Oguz, S.S. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Preterm Infants Treated with Oral Paracetamol Versus Ibuprofen for Patent Ductus Arteriosus. Am. J. Perinatol. 2017, 34, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juujärvi, S.; Saarela, T.; Hallman, M.; Aikio, O. Trial of paracetamol for premature newborns: Five-year follow-up. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021, 21, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, J.F.; Patil, A.S.; Langman, L.J.; Penn, H.J.; Derleth, D.; Watson, W.J.; Brost, B.C. Transplacental Passage of Acetaminophen in Term Pregnancy. Am. J. Perinatol. 2017, 34, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Addo, K.A.; Bulka, C.; Dhingra, R.; Santos, H.P., Jr.; Smeester, L.; O’Shea, T.M.; Fry, R.C. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy and DNA methylation in the placenta of the extremely low gestational age newborn (ELGAN) cohort. Environ. Epigenet. 2019, 5, dvz010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Green, B.B.; Karagas, M.R.; Punshon, T.; Jackson, B.P.; Robbins, D.J.; Houseman, E.A.; Marsit, C.J. Epigenome-Wide Assessment of DNA Methylation in the Placenta and Arsenic Exposure in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study (USA). Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maccani, J.Z.; Koestler, D.C.; Houseman, E.A.; Armstrong, D.A.; Marsit, C.J.; Kelsey, K.T. DNA methylation changes in the placenta are associated with fetal manganese exposure. Reprod. Toxicol. 2015, 57, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marsit, C.J.; Maccani, M.A.; Padbury, J.F.; Lester, B.M. Placental 11-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase methylation is associated with newborn growth and a measure of neurobehavioral outcome. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Slattery, W.T.; Klegeris, A. Acetaminophen metabolites p-aminophenol and AM404 inhibit microglial activation. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflammation 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fride, E.; Gobshtis, N.; Dahan, H.; Weller, A.; Giuffrida, A.; Ben-Shabat, S. The endocannabinoid system during development: Emphasis on perinatal events and delayed effects. Vitam. Horm. 2009, 81, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecharz-Klin, K.; Piechal, A.; Jawna-Zboińska, K.; Pyrzanowska, J.; Wawer, A.; Joniec-Maciejak, I.; Widy-Tyszkiewicz, E. Paracetamol—Effect of early exposure on neurotransmission, spatial memory and motor performance in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 323, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, I.V.; Cirulli, E.T.; Mitchell, M.W.; Jonsson, T.J.; Yu, J.; Shah, N.; Spector, T.D.; Guo, L.; Venter, J.C.; Telenti, A. Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) Use Modifies the Sulfation of Sex Hormones. EBioMedicine 2018, 28, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Database: Ovid Medline |

|---|

|

| Database: Ovid Embase |

|

| Database: Web of Science |

|

| Study | Design | Aim | Population | Sample Size | Age * | Exposure Time (WGA) | Dose (mg/kg) and Interval | Duration | Cumulative Dose | Outcomes | Assessment Time (Years) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (years) | (mg/kg) | |||||||||||

| Bauer 2013 [22] | Ecologic | Relationship of population weighted average of ASD and paracetamol use | 20 studies on health outcomes and paracetamol use | N/R | N/R | N/R | Paracetamol | ASD | N/R | Biologic plausibility along with clinical evidence is linking paracetamol to ASD and abnormal NDV | ||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||

| pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Stergiakouli 2016 [23] | PC | Association between behavioral problems and paracetamol use | Cases | ≤18: | 29.1 | ≤18 | Paracetamol | Behavior problems | 7 | Children with prenatal exposure to paracetamol have ↑ risk of behavior difficulties that are not explained bybehavior or social factors linked to paracetamol use | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | 4415 | −4.5 | ≤32 | |||||||||

| ≤32: | ||||||||||||

| 3381 | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| Controls | 4681 | 29.2 | ≤18 | Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||

| Mother–child pairs without paracetamol exposure | −4.5 | ≤32 | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||

| Andersen 2012 [35] | PC | Risk of asthma and paracetamol exposure | Cases | 976 | N/R | 30 days before the 1st day of LMP - | Paracetamol | Asthma | Birth until the date of asthma diagnosis, death, emigration or the end of cohort follow-up | Robust association between maternal prenatal paracetamol exposure and the risk of asthma in offspring | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | delivery | |||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Controls | 196,084 | Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||

| Mother-child pairs

without paracetamol exposure | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Bertoldi 2019 [24] | PC | Risk of NDV adverse outcomes with paracetamol exposure | Cases | Cases | Viva: | Viva: | Paracetamol | NDV outcomes | 2-3 | No strong evidence of a negative association between prenatal paracetamol use and cognition in early childhood | ||

| Cohorts of Viva and Pelotas studies: Mother–child pairs with exposure to paracetamol | Viva | 32.5 (5.0) | T1/ T2, | |||||||||

| T1/ T2: 837 | T1 and T2 | |||||||||||

| T1 and T2: | Pelatos: | Pelotas: | ||||||||||

| 487 | 27.1 (6.6) | T1/ T2, | ||||||||||

| Pelotas: | T1 and T2 | |||||||||||

| T1/T2: | T1/T2/T3 | |||||||||||

| 2198 | T1, T2 and T3 | |||||||||||

| T1 and T2: | ||||||||||||

| 1274 | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| Control | Control | Viva: | Other Pharmacotherapy | |||||||||

| Cohorts of Viva and Pelotas studies: Mother–child pairs without exposure to paracetamol | Viva: | T1/ T2 | ||||||||||

| T1/T2: 361 | 32 (5.2) | |||||||||||

| T1 and T2: 692 | T1 and T2 | |||||||||||

| Pelotas T1/T2: 1620 | 32 (5.1) | |||||||||||

| T1 and T2: 2544 | Pelotas: | |||||||||||

| T1/T2/ | T1/T2 26.7 (6.7) | |||||||||||

| T3: | T1 and T2 | |||||||||||

| 1348 | 26.9 (6.6) | |||||||||||

| T1, T2 and T3: | T1/T2/ T3 | |||||||||||

| 3044 | 26.8 (6.6) | |||||||||||

| T1, T2 and T3 | ||||||||||||

| 27 (6.6) | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| Ji 2020 [26] | PC | Association between cord plasma biomarkers of paracetamol exposure and risk of ADHD and ASD | Cases | Cases | <20: | Paracetamol | ADHD, ASD and other DDs | 0–21 | Prenatal paracetamol exposure is associated with an increased risk of ADHD and ASD | |||

| Mother–child pairs with maternal cord paracetamol burden in the T1 or T2 | T1: 332 | 65 (11.85) | ||||||||||

| T2: 332 | 20–34: 728 (70.99) | |||||||||||

| ≥ 35: 183 (17.15) | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Controls | Controls | Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs with maternal cord paracetamol burden in the T3. | T3: 332 | |||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Garcia-Marcos, 2009 [36] | Epidemiologic | Paracetamol exposure and prevalence of wheezing, modified by maternal asthma | Cases | Mothers with asthma and exposure: | N/R | N/R | Paracetamol | Wheezing | 4-5 | The frequent usage of paracetamol during pregnancy is associated with the prevalence of wheezing in offspring during preschool years | ||

| Survey | Pairs of mothers with asthma and their children exposed to paracetamol | 34 | ||||||||||

| (1) ≥1 | Non-asthmatic mothers with exposure: | |||||||||||

| in pregnancy | 901 | |||||||||||

| (2) ≥1/month | N/R | ≥1 | N/R | |||||||||

| pregnancy | ≥1/m | |||||||||||

| Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||||

| Asthmatic mothers without exposure: | ||||||||||||

| Controls | 31 | |||||||||||

| Pairs of mothers with asthma and their children never exposed to paracetamol | Non-asthmatic mothers without exposure: | |||||||||||

| 775 | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Golding 2020 | PC | Paracetamol exposure and childhood behavioral and cognitive outcomes | Cases | Cases | N/R | 18–32 | Paracetamol | Cognitive and behavior outcomes | 0.5–17 | Prenatal paracetamol exposure is associated with child attention and hyperactivity and conduct problems in boys | ||

| [27] | Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | 5279 | ||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||||

| Controls | Controls | N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||

| Mother–child pairs without paracetamol exposure | 6, 746 | |||||||||||

| Ji 2018 [25] | PC | Association between maternal | Cases | Above median | <35: | N/R | Paracetamol | ADHD, ASD and other DDs | 7 | Maternal plasma biomarkers of paracetamol are | ||

| plasma | Mother–child pairs with maternal paracetamol biomarkers of | 668 | 965 | associated with ↑ risk of ADHD | ||||||||

| biomarkers of paracetamol and ADHD in offspring | (1) above median | Below median | ≥35: | |||||||||

| (2) below median | 630 | 215 | ||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Controls | Controls | |||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs with maternal paracetamol biomarkers of | 1062 | |||||||||||

| “no detection” | ||||||||||||

| Bakkeheim | PC | Paracetamol exposure and allergic disease in school-aged children | Cases | T1: 31 | N/R | T1 and T2 | Paracetamol | Primary: current asthma, | 10 | Paracetamol exposure in pregnancy was associated with allergic rhinitis, but not with asthma or allergic sensitization | ||

| 2011 [44] | Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | allergic sensitization, allergic rhinitis | ||||||||||

| T2/T3: 32 | Secondary: | |||||||||||

| history of asthma, | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | current wheeze, | |||||||||

| FeNO > 16.7 (ppb), | ||||||||||||

| Mild-to-moderate bronchial hyper-responsiveness, | ||||||||||||

| Controls | 972 | Other pharmacotherapy | severe bronchial hyper-responsiveness | |||||||||

| Mother–child pairs without paracetamol exposure | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Piler 2018 [37] | PC | Association between paracetamol exposure and asthma in offspring. | Cases | 170 | Cases: | <20 | Paracetamol | Asthma | 3, 5, 7 and 11 | The combination of prenatal and postnatal paracetamol exposure leads to higher risk of asthma development | ||

| Mother–child | <19: 0.8% | |||||||||||

| pairs with exposure to paracetamol | 20–24: 1.2% | |||||||||||

| 25–30: 1.5% | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| >31: 2.2% | ||||||||||||

| Controls | No paracetamol exposure: 3324 | Controls: | Other pharmacotherapy | |||||||||

| Mother–child pairs | paracetamol and aspirin exposure: 97 | <18.5 | ||||||||||

| (1) without paracetamol exposure | aspirin exposure: 532 | 18.5–24.9: | ||||||||||

| (2) with exposure to paracetamol and aspirin | <19: 41.6% | |||||||||||

| (3) with exposure to aspirin | 20–24: 35.1% | |||||||||||

| 25–30: 25.0% | ||||||||||||

| >31: 30.9% | ||||||||||||

| Aspirin | Aspirin | Aspirin | ||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Shaheen 2002 [49] | LC | Association between paracetamol use and risk of wheezing and eczema | Cases | 9400 | N/R | <20 | Paracetamol | Wheezing, eczema | Wheezing: 3.9 | Frequent use of paracetamol in late pregnancy may ↑ the risk of wheezing in the offspring | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | ||||||||||||

| 20–32 | Eczema: | |||||||||||

| 2.5 | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Controls | ||||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs | Other pharmacotherapy | |||||||||||

| (1) without paracetamol exposure | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| (2) with prenatal aspirin exposure | ||||||||||||

| Ernst 2019 [45] | LC | Association between paracetamol exposure and timing of pubertal development | Cases | 8606 | Cases: | <12 | Paracetamol | Pubertal development | 11.5 and q 6 ms until full sexual maturation or 18 | Prenatal paracetamol use may have long-term effects on female offspring pubertal development | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | 30.6 (4.4) | 13–24 | ||||||||||

| >25 | ||||||||||||

| Controls | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| 30.7 (4.4) | ||||||||||||

| Controls | Other pharmacotherapy | |||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs without paracetamol exposure | ||||||||||||

| 7216 | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Jedrychowski 2011 [39] | PC | Association between low exposure to paracetamol and eczema in early childhood and interaction with exposure to pollutants | Cases | Cases | 28.82 (3.39) | T1/ T2/T3 | Paracetamol | Eczema | 0.3–2 -> q 3 ms | Very small doses of paracetamol in pregnancy may affect the occurrence of eczema in early childhood, but only with co-exposure to high concentrations of fine particulate matter | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure in T1/T2/T3 | T1: 40 | |||||||||||

| T2: 40 | 2–5 -> q 6 ms | |||||||||||

| T3: 73 | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | T1: | ||||||||||

| 200 | ||||||||||||

| (500–1500) | ||||||||||||

| T2: | ||||||||||||

| 1600 | ||||||||||||

| (500–1100) | ||||||||||||

| T3: | ||||||||||||

| 2200 | ||||||||||||

| (500–8000) | ||||||||||||

| T1/T2/T3: 2600 | ||||||||||||

| (500–1600) | ||||||||||||

| Controls | Controls | Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs without paracetamol exposure in T1 or T2 or T3 | T1: 283 | |||||||||||

| T2: 283 | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| T3: 248 | ||||||||||||

| Vlenterie 2016 [28] | PSM | Association between | Cases | 20,749 | <25: 155 | N/R | Paracetamol | Psychomotor behavior/temperament problems | 1.5 | Long-term prenatal exposure to paracetamol associated with ↑ risk of motor milestone delay and impaired communication | ||

| Cohort | NDV impairment with exposure to paracetamol | Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | 25–29: | |||||||||

| 594 | ||||||||||||

| 30–34: | ||||||||||||

| 805 | ||||||||||||

| ≥35: 345 | ||||||||||||

| Controls | 30,451 | <25: 3069 | ||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs without paracetamol exposure | 25–29: | |||||||||||

| 10,183 | ||||||||||||

| 20–34: 11,87 | ||||||||||||

| >35: 5329 | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Fisher 2016 [46] | PC | Relationship between | Cases | <8 | Male: | 0, 0.25, 1, 1.5 and 2 | Prenatal paracetamol exposure during 8–14 weeks of gestation associated with shorter AGD | |||||

| paracetamol | Mother–male child pairs with paracetamol exposure | AGD, penile length, testicular descent distance, cryptorchidism | ||||||||||

| intake and male infant genital development | 14-Aug | Paracetamol | Female: AGD | |||||||||

| >14 | ||||||||||||

| 33.5 | 33.5 | 3 | ||||||||||

| (0.5–360.0). | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | |||||||||||

| Controls | ||||||||||||

| Mother–male child pairs without paracetamol exposure | Other pharmacotherapy | |||||||||||

| 456 | 33.5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||||||

| Lind 2017 [47] | PC | Association between analgesic exposure and AGD in offspring | Cases | Paracetamol exposure only: | 30.9 | T1/T2 | AGD | 0.25 | The negative association between prenatal analgesic exposure and AGD in male offspring suggests disruption of androgen action | |||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | 365 | Paracetamol | ||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Controls | No analgesic exposure: | |||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs with exposure to | 617 | |||||||||||

| (1) analgesic | Paracetamol and other analgesic exposure: | Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||

| (2) paracetamol and other analgesic | 34 | |||||||||||

| (3) other analgesics | Other analgesics only: | |||||||||||

| 11 | ||||||||||||

| N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||

| Persky 2008 [40] | Cohort ** | Association between paracetamol exposure and wheezing and allergic symptoms | Cases | Early pregnancy: | 25.8 | T1: | Wheezing, wheezing/ | 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1 | Paracetamol use in middle to late but not early pregnancy may be related to respiratory symptoms | |||

| Mother–child pairs with exposure to paracetamol | 344 | [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] | 16–27 | Paracetamol | coughing emergency department visits, hospitalization, asthma | |||||||

| (1) early pregnancy | Middle-to-late pregnancy: | T2: 28–36 | ||||||||||

| (2) middle to late pregnancy | 342 | |||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Controls | ||||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs with | Aspirin: 9 | Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||

| (1) exposure to aspirin | Ibuprofen: 11 | |||||||||||

| (2) exposure to ibuprofen | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Petersen 2018 [34] | PC | Association between exposure to paracetamol, aspirin or ibuprofen and risk of CP in offspring | Cases | Total cohort | T1 | Overall CP, unilateral spastic CP | 1 to 6 | Children with T2 paracetamol exposure have ↑ risk of unilateral spastic CP | ||||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | ≤24: 19,318 | Paracetamol | ||||||||||

| 25–29: | T2 | |||||||||||

| 66,037 | ||||||||||||

| 91,015 | 30–34: | T3 | ||||||||||

| 70,268 | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| ≥35: | ||||||||||||

| 29,994 | ||||||||||||

| Controls | Aspirin: 5746 | |||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs with | ||||||||||||

| (1) aspirin exposure | ibuprofen: 7358 | Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||

| (2) ibuprofen exposure | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Rebordosa 2018[41] | PC | Association between paracetamol exposure and asthma/ wheezing | Cases | Cases | T1/T2/T3 | 18 month cohort: | Paracetamol | Asthma/ | 1.5 or 7 | Prenatal paracetamol exposure has moderate associations with asthma | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | 18 month cohort: | <24: | bronchitis; wheezing; hospitalization for asthma | |||||||||

| 54,530 | 5525 | . | ||||||||||

| 7 year cohort: | 25–29: | |||||||||||

| 9546 | 25,601 | |||||||||||

| 30–35: | ||||||||||||

| 25,076 | ||||||||||||

| ≥36: | ||||||||||||

| 10,147 | ||||||||||||

| 7 year cohort: | ||||||||||||

| <24: | ||||||||||||

| 1059 | ||||||||||||

| 25–29: | ||||||||||||

| 4732 | ||||||||||||

| 30–35: | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| 5041 | ||||||||||||

| >36: | ||||||||||||

| 1864 | ||||||||||||

| Controls | Other pharmacotherapy | |||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs without prenatal paracetamol exposure | Controls | N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||

| 18 month cohort: | ||||||||||||

| 30,129 | ||||||||||||

| 7 year cohort: | ||||||||||||

| 5981 | ||||||||||||

| Ystrom 2017 [29] | PC | Association between prenatal paracetamol exposure and ADHD in offspring | Cases | Cases: | N/R | 6 months before pregnancy | Paracetamol | ADHD | 3 years until diagnosis | Long-term prenatal paracetamol exposure is associated with ADHD | ||

| Mother–child pairs with prenatal paracetamol exposure | 52,707 | |||||||||||

| 0–4, 5–8, 9–12, 13–16, 17–20, 21–24, 25–28, | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| > 29, >30 | ||||||||||||

| Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||||

| Controls | Controls: | N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||

| Mother–child pairs without paracetamol | 60,266 | |||||||||||

| Exposure | ||||||||||||

| Liew 2016 [30] | PC | Association between paracetamol exposure and behavior problems/HKDs in offspring. | Cases | Total Cohort: | 30.8 | Trimesters 1, 2 and 3 | Paracetamol | Behavior problems, | 5, 7 | Prenatal paracetamol exposure appears to be associated with increased risk of behavioral problems and HKDs | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | 1491 | −4.4 | HKDs | |||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Controls | 30.8 | |||||||||||

| Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs without prenatal paracetamol exposure | −4.2 | N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||

| Rifas-Shiman2020 [31] | PC | Association between paracetamol and ibuprofen exposure and executive function/behavior problems in offspring | 9.9 | Paracetamol | Executive function and behavior problems | 1, 8 | Prenatal exposure to paracetamol is associated with poorer executive function in children | |||||

| Cases | Total Cohort: | 32.2 | ||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | 1225 | −5.2 | ||||||||||

| 27.9 | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Controls | Other pharmacotherapy | |||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| (1) without paracetamol exposure | ||||||||||||

| (2) with ibuprofen exposure | ||||||||||||

| Streissguth,1987 [32] | PC | Association between paracetamol/ aspirin exposure and IQ/attention in offspring | Cases | Total Cohort: | N/R | 22 | Paracetamol | N/R | 4 | Prenatal paracetamol exposure was not associated with child IQ or attention | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | 1529 | |||||||||||

| Follow-up at 4 years: 421 | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| Controls | ||||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs | ||||||||||||

| (1) without paracetamol exposure | ||||||||||||

| (2) with aspirin exposure | ||||||||||||

| Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Thompson 2014 [33] | PC | Association between paracetamol use and ADHD in offspring | Cases | Cases | N/R | N/R | Paracetamol | ADHD | 7 and 11 | Prenatal paracetamol exposure increases risk of | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | (437) 49.8 | N/R | N/R | N/R | ADHD-like behaviors | |||||||

| Controls | Anti-inflammatory drugs: 11 | |||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs | −1.3 | Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||

| (1) without paracetamol exposure | Aspirin: 46 (5.3) | |||||||||||

| (2) with exposure to other drugs | Antacid: 151 | |||||||||||

| −17.4 | ||||||||||||

| Antibiotics: 204 | ||||||||||||

| −23.5 | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Magnus 2016 [42] | PC | Association between paracetamol exposure and asthma in offspring | Cases | Assessed at | <25: 1432 (30.1) | ≤18 | Paracetamol | Asthma | 3 and 7 years | Prenatal paracetamol exposure independently associated with asthma-related outcomes | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | 3 years: | 25–29: 4927 (27.8) | ≤30 | |||||||||

| 53,169 | 30–34: 5876 (27.8) | <6 months postpartum | ||||||||||

| Controls | 7 years: | ≥35: 2606 (27.3) | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||

| Mother–child pairs without prenatal paracetamol exposure | 25,394 | Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||

| <25: | ||||||||||||

| 1712 (36.0) | ||||||||||||

| 25–29: 6522 (36.8) | ||||||||||||

| 30–34: 7820 (37.0) | ||||||||||||

| ≥35: 3857 (40.4) | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| Sordillo 2015 [43] | PC | Association between antipyretic exposure and asthma in offspring | Cases | 992 | 32.2 | Pregnancy | Paracetamol | Wheeze, asthma, | 3–5, 7–10 | Adjustment for respiratory infections in early life substantially diminished associations between infant antipyretics and early childhood asthma | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | −5.2 | allergen sensitization | ||||||||||

| N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||

| Controls | Without paracetamol exposure: 430 | |||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs | ||||||||||||

| (1) without paracetamol exposure | With ibuprofen exposure: | |||||||||||

| (2) with ibuprofen exposure | 247 | Alternative pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||

| N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||

| Snijder,2011 [48] | PC | Association between analgesic exposure and cryptorchidism/hypospadias | Cases | 2388 | 29.96 | Periconception; | Paracetamol | Cryptorchidism, hypospadias | 2.5 | Prenatal exposure to paracetamol | ||

| Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | −75 | −5.24 | increases risk of cryptorchidism in offspring | |||||||||

| <14 WGA; | ||||||||||||

| 14–22 WGA; | ||||||||||||

| 20–32 WGA | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Controls | NSAID: | |||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs with | 414 (13) | |||||||||||

| (1) No prenatal analgesic exposure | ||||||||||||

| (2) NSAID exposure | Other analgesic: 382 (12) | |||||||||||

| (3) other analgesics exposure | Other pharmacotherapy | |||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | ||||||||||

| Shaheen 2010 [36] | LC | Association of paracetamol | Cases | Total cohort 13,988 | 27.2 | <18–20 | Paracetamol | Wheezing, asthma, eczema, hay fever; | 7, 7.5 and 8.5 | Maternal antioxidant gene polymorphisms may modify the relation between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and childhood asthma | ||

| exposure and antioxidant genotypes on childhood asthma | Mother–child pairs with paracetamol exposure | −5 | 20–32 | lung function | ||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | atopy | |||||||||

| Controls | Other pharmacotherapy | |||||||||||

| Mother–child pairs without paracetamol exposure | N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||

| Study | Design | Aim | Population | Sample Size | GA(weeks) | BW (kg) | PNA at Exposure | Dose (mg/kg) and Interval | Duration | Cumulative Dose (mg/kg) | Outcomes | Assessment Time (years) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bauer, 2013[22] | Ecologic | Paracetamol use in early childhood and ASD | Cases 9 countries with data on circumcision and ASD after 1995 | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | Paracetamol | ASD | N/R | Country- and state- level correlations between indicators of prenatal and neonatal paracetamol exposure and ASD | ||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||||

| Controls 12 countries with data on circumcision and ASD before 1995 | Other pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||||

| N/R | N/R | N/R | |||||||||||

| Oncel 2017 [50] | RCT Follow-Up | The effects of paracetamol vs. ibuprofen on NDV outcomes | Cases Preterm infants with PDA on oral paracetamol | 30 | 28 (1.7) | 0.99 (0.21) | 2-3 | Paracetamol | NDV outcomes; hearing and vision | 1.5–2 | No evidence for significant difference in NDV outcomes for paracetamol vs. ibuprofen | ||

| 15, q 6 h | 3 | N/R | |||||||||||

| Controls Preterm infants with PDA on oral ibuprofen | 31 | 27.6 (1.9) | 0.98 (0.18) | Other pharmacotherapy | |||||||||

| Ibuprofen: 10, 5, 5, q 24 h. | 2 | N/R | |||||||||||

| Juujarvi, 2021 [51] | RCT Follow-Up | The effects of IV paracetamol and NDV outcome | Cases Preterm infants with PDA on IV paracetamol | 23 | 23 + 5 to 31 + 6 | 1.22 (0.43) | 1–4 | Paracetamol | NDV | 2 | No long-term adverse reactions of IV paracetamol | ||

| 20, 7.5, q 6 h | 4 | 126 | |||||||||||

| Controls Preterm infants with PDA on IV placebo | 21 | 23 + 5 to 31 + 6 | 1.12 (0.34) | Other pharmacotherapy Placebo or standard practice | |||||||||

| 0.45% saline | 4 | N/R | |||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patel, R.; Sushko, K.; van den Anker, J.; Samiee-Zafarghandy, S. Long-Term Safety of Prenatal and Neonatal Exposure to Paracetamol: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042128

Patel R, Sushko K, van den Anker J, Samiee-Zafarghandy S. Long-Term Safety of Prenatal and Neonatal Exposure to Paracetamol: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042128

Chicago/Turabian StylePatel, Ram, Katelyn Sushko, John van den Anker, and Samira Samiee-Zafarghandy. 2022. "Long-Term Safety of Prenatal and Neonatal Exposure to Paracetamol: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042128

APA StylePatel, R., Sushko, K., van den Anker, J., & Samiee-Zafarghandy, S. (2022). Long-Term Safety of Prenatal and Neonatal Exposure to Paracetamol: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042128