Caregivers’ Experience of End-of-Life Stage Elderly Patients: Longitudinal Qualitative Interview

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Samples

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Analysis

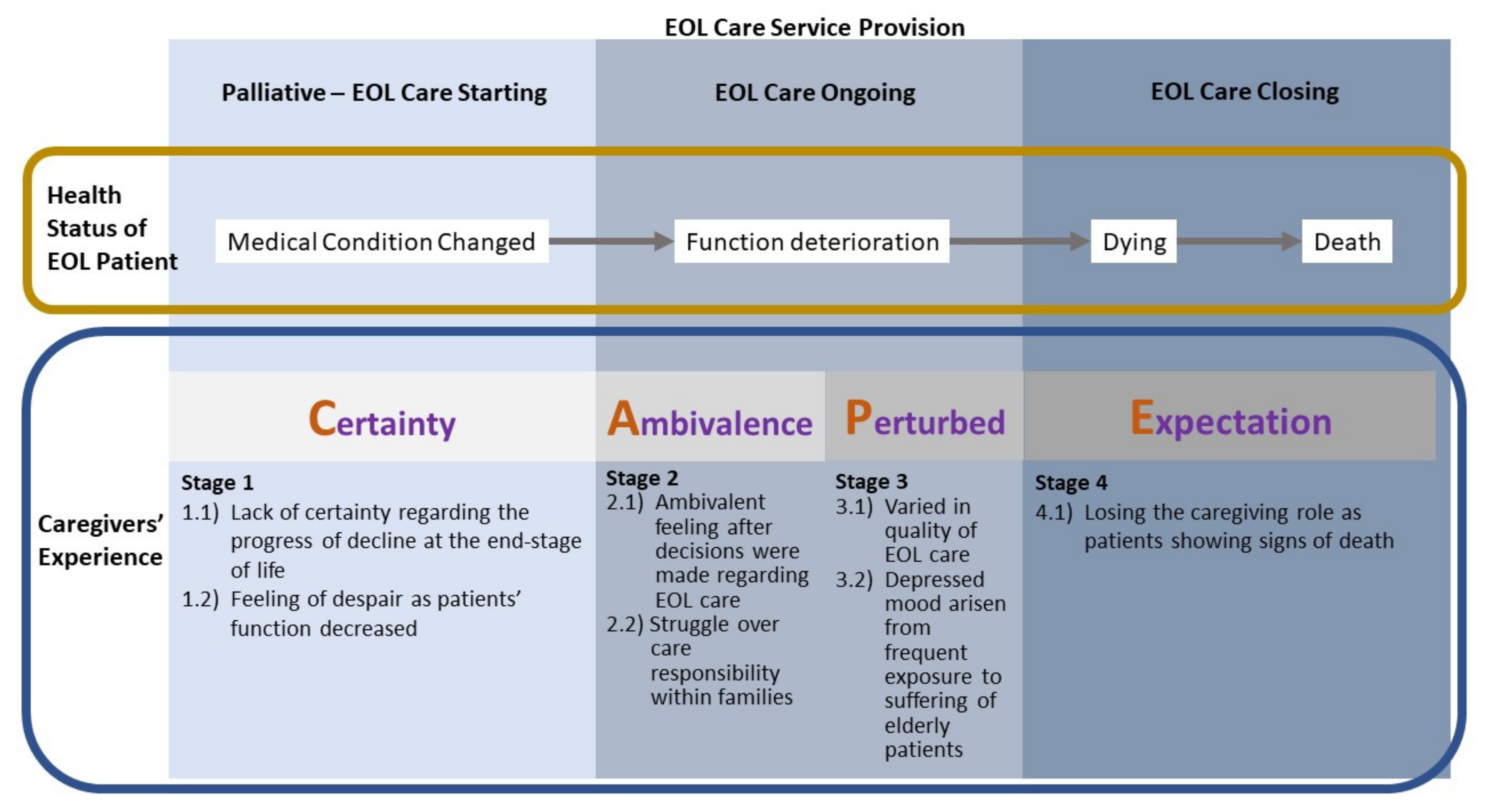

3. Findings

3.1. Stage 1 Certainty

3.1.1. Lack of Certainty Regarding the Progress of Decline at the End-Stage of Life

I used to go along with him when he was required to be sent to the hospital by ambulance, but recently, I could not. I felt like I was out of control!…Everything is fast…sudden. Because of the unknown… I felt scared whenever I received the phone call…(Case 7)

3.1.2. Feeling of Despair as Patients’ Function Decreased

My husband has lost both emotional and physical feelings because of the pain. The skin on his ear is no longer intact. There are wounds here and there with reddish coloured skin patches. Every time I return home after visiting him at the nursing home, I start to cry…!(Case 7)

I am feeling ok, this (deterioration) is part of the life process. What is important is that if she really has to go, she can pass away comfortably. It really doesn’t matter… it doesn’t concern me.(Case 4)

When you look after a baby, you are full of joy because (s)he is growing. However, when you look after your mother, you are very sad as you see her deteriorating day by day. Therefore, it’s different… you’re sorrowful while looking after your mother!(Case 4)

3.2. Stage 2 Ambivalence

3.2.1. Ambivalent Feeling after Decisions Were Made Regarding EOL Care

After all, I said to her, “We’re not trying to send you away (by causing death), but we just do not want you to suffer!” I cried immediately after I spoke to her!… When I looked at her, I wish she could leave (the world), but I would not want to because I miss her. I am so ambivalent!(Case 5)

After all, I’m still concerned whether I should present the form immediately (when my mom is admitted to the hospital)… in case my mom has low blood pressure, I wonder whether they (healthcare providers) would ask physicians if there is anything they could do or whether they might just simply leave her because we had signed the DNR form.(Case 14)

3.2.2. Struggle over Care Responsibility within Families

My friends asked me to relax and take a 1–2 days tour during which we could have some food. However, I would not feel at ease because what if something happened to him while I was away!… I would feel guilty for my dereliction of duty….(Case 12)

When I felt sick and could not even get out of bed, I still needed to get up anyway to take care of my mom! I felt very helpless at that moment but, I could not tell my brothers and sisters. I could not make any complaints to them.(Case 1)

Yes, I do have expectations, but I ended with disappointment… oh well, just let them be, they’re adults! Everyone has a family, and everyone has a job! I always tell myself that I’d do whatever I can. I would not care about others.(Case 5)

3.3. Stage 3 Perturbed

3.3.1. Varied in Quality of EOL Care

All nursing staff are employed from mainland China, and they have inadequate knowledge and very little compassion… For example, my helper told me that the bathroom was very dirty because the elderly sit on commode chairs when they shower, which meant that they often urinate at the same time… I cannot complain because after all, my mom requires their care. So I’m in a very difficult position.(Case 3)

My mom was readmitted to the A&E within less than 24 h, and because you are admitted to A&E again (instead of a convalescent hospital), they will treat it as a new episode. She had to go through the tests again, including X-ray, blood tests and other investigations, and this actually made her suffer!(Case 3)

The doctor even said to me, “I do not recognize this (EOL) programme. I’m here to cure patients and I do not think that your mom is sick enough to die soon!”(Case 9)

3.3.2. Depressed Mood Arisen from Frequent Exposure to Suffering of Elderly Patients

In fact, of those admitted to this ward…many of the elderly passed away…and most of them were very frail… They neither ate nor took care of themselves. In addition, they moaned sometimes. Seeing these things made me feel really uncomfortable.(Case 3)

While feeding her mother, our participant looked across the room at an old lady who was breathing heavily, with no one beside her. The daughter then turned around and looked at the researcher and said, “She’s going to die soon! Isn’t it depressing to see all these people around?”(Case 9)

3.4. Stage 4 Expectation

Losing the Caregiving Role as Patients Showing Signs of Death

I’m not sure whether my mom knew what she was doing. I want to buy her food, but she cannot eat. I wish to have a chat with her, but she cannot speak… I feel so much pain for her!(Case 5)

As I observed that her condition was getting worse, I felt that she was leaving us soon. I got more sensitive to everything surrounding her. They (memories) come and go like a flash!… There are things I wish I could have done with her…!(Case 3)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martín, J.M.; Olano-Lizarraga, M.; Saracíbar-Razquin, M. The experience of family caregivers caring for a terminal patient at home: A research review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 64, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belasco, A.; Barbosa, D.; Bettencourt, A.R.; Diccini, S.; Sesso, R. Quality of life of family caregivers of elderly patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2006, 48, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzuya, M.; Enoki, H.; Hasegawa, J.; Izawa, S.; Hirakawa, Y.; Shimokata, H.; Akihisa, I. Impact of caregiver burden on adverse health outcomes in community-dwelling dependent older care recipients. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenmakers, B.; Buntinx, F.; Delepeleire, J. Factors determining the impact of care-giving on caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. A systematic literature review. Maturitas 2010, 66, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil, K.; Thabane, L.; Foster, G.; Bédard, M. Gender differences among Canadian spousal caregivers at the end of life. Health Soc. Care Community 2009, 17, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grov, E.K.; Fosså, S.D.; Sørebø, Ø.; Dahl, A.A. Primary caregivers of cancer patients in the palliative phase: A path analysis of variables influencing their burden. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 2429–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monin, J.K.; Schulz, R. Interpersonal effects of suffering in older adult caregiving relationships. Psychol. Aging 2009, 24, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirst, M. Trends in informal care in Great Britain during the 1990s. Health Soc. Care Community 2001, 9, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, J.M.; Kramer, B.J. Family caregivers in palliative care. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2004, 20, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, A.Y.; Liu, C.F.F.; Szeto, Y. The difficulties faced by informal caregivers of patients with terminal cancer in Hong Kong and the available social support. Cancer Nurs. 2003, 26, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Office, Legislative Council Secretariat. Reserch Brief (Issue No. 1 2015-2016)—Challenges of Population Ageing; Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Hong Kong, China, 2015. Available online: https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/1516rb01-challenges-of-population-ageing-20151215-e.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Chui, E.W.T.; Chan, K.S.; Chong, A.M.L.; Ko, L.S.F.; Law, S.C.K.; Law, C.K.; Leung, E.M.F.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Lou, V.W.Q.; Ng, S.Y.T. Elderly Commission’s Study on Residential Care Services for the Elderly; The University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, China, 2009. Available online: https://www.elderlycommission.gov.hk/en/download/library/Residential%20Care%20Services%20-%20Final%20Report(eng).pdf (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Chan, C.Y.; Cheung, G.; Martinez-Ruiz, A.; Chau, P.Y.K.; Wang, K.; Yeoh, E.K.; Wong, E.L.Y. Caregiving burnout of community-dwelling people with dementia in Hong Kong and New Zealand: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods (Applied Social Research Methods), 5th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, S.A.; Kendall, M.; Carduff, E.; Worth, A.; Harris, F.M.; Lloyd, A.; Cavers, D.; Grant, L.; Sheikh, A. Use of serial qualitative interviews to understand patients’ evolving experiences and needs. BMJ 2009, 339, b3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, K.; Wilson, J.A. GSF Team—National Glod Standards Framwork Centre in End of Life Care. In The Gold Standards Framework Prognostic Indicator Guidance (PIG), 6th ed.; 2016; Available online: https://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/PIG/NEW%20PIG%20-%20%20%2020.1.17%20KT%20vs17.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Lowers, J.; Scardaville, M.; Hughes, S.; Preston, N.J. Comparison of the experience of caregiving at end of life or in hastened death: A narrative synthesis review. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.A. Family members’ experiences with decision making for incompetent patients in the ICU: A qualitative study. Am. J. Crit. Care 1998, 7, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, T.; Twinn, S.; Yan, E. The attitudes of Chinese family caregivers of older people with dementia towards life sustaining treatments. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 58, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilden, V.P.; Tolle, S.W.; Nelson, C.A.; Fields, J. Family decision-making to withdraw life-sustaining treatments from hospitalized patients. Nurs. Res. 2001, 50, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.Y.; Siminoff, L.A. The role of the family in treatment decision making by patients with cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2003, 30, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lo, B.; Quil, T.; Tulsky, J. Discussing palliative care with patients. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 130, 744–749. [Google Scholar]

- Torke, A.M.; Garas, N.S.; Sexson, W.; Branch, W.T., Jr. Medical care at the end of life: Views of African American patients in an urban hospital. J. Palliat. Med. 2005, 8, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Krishna, L.; Kwee, A. Should patients and family be involved in “Do not resuscitate” decisions? Views of oncology and palliative care doctors and nurses. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2012, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, R.; List, S.; Epiphaniou, E.; Jones, H. How can informal caregivers in cancer and palliative care be supported? An updated systematic literature review of interventions and their effectiveness. Palliat. Med. 2012, 26, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P.L.; Aranda, S.; Hayman-White, K. A psycho-educational intervention for family caregivers of patients receiving palliative care: A randomized controlled trial. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2005, 30, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, M.M.; Newcomb, P. Self-efficacy and Stress Among Informal Caregivers of Individuals at End of Life. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2018, 20, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.L.Y.; Coulter, A.; Cheung, A.W.L.; Yam, C.H.K.; Yeoh, E.K.; Griffiths, S.M. Patient experiences with public hospital care: First benchmark survey in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med. J. 2012, 18, 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, E.L.Y.; Coulter, A.; Cheung, A.W.L.; Yam, C.H.K.; Yeoh, E.K.; Griffiths, S. Validation of inpatient experience questionnaire. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2013, 25, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.L.Y.; Coulter, A.; Hewitson, P.; Cheung, A.W.L.; Yam, C.H.K.; Lui, S.F.; Tam, W.W.W.; Yeoh, E.K. Patient experience and satisfaction with inpatient service: Development of short form survey instrument measuring the core aspect of inpatient experience. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, C.L.; Chui, E.W. Association between cultural factors and the caregiving burden for Chinese spousal caregivers of frail elderly in Hong Kong. Aging Ment. Health 2011, 15, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T.; Chan, A.C.M. Filial piety and psychological well-being in well older Chinese. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, P262–P269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.P.; Yi, C.C. Filial norms and intergenerational support to aging parents in China and Taiwan. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2011, 20 (Suppl. 1), S109–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skilbeck, J.; Seymour, J. Meeting complex needs: An analysis of Macmillan nurses’ work with patients. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2002, 8, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, L.; Stajduhar, K.; Toye, C.; Aoun, S.; Grande, G.; Todd, C. Home-based family caregiving at the end of life: A comprehensive review of published qualitative research (1998–2008). Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andershed, B. Relatives in end-of-lfe care: A systematic review of the literature the five last years, January 1999–February 2004. J. Clin. Nurs. 2006, 15, 1158–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Galan, A.M.; Ruiz-Fernandez, M.D.; Carmona-Rega, M.I.; Cabrera-Troya, J.; Ortíz-Amo, R.; Ibáñez-Masero, O. The Experiences of fami8ly caregivers at the end of life: Suffering, compassion satisfaction and support of health care professionals. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 21, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odgers, J.; Fitzpatricks, D.; Penney, W.; Wong, A.S. No one said he was dying: Families’ experiences of end-of-life care in an acute setting. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 35, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, E.L.Y.; Kiang, N.; Chung, R.Y.; Lau, J.; Chau, P.Y.K.; Wong, S.Y.D.; Woo, J.; Chan, E.Y.Y.; Yeoh, E.K. Quality of Palliative and End-Of-Life Care in Hong Kong: Perspectives of Healthcare Providers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.Y.; Wong, E.L.Y. Assessing Medical Students’ Confidence towards Provision of Palliative Care: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.Y.; Wong, E.L.Y. The Role Complexities in Advance Care Planning for End-of-Life Care-Nursing Students’ Perception of the Nursing Profession. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) | |

| N (%) | |

| Age | |

| 70–79 | 4 (28.6) |

| 80–89 | 4 (28.6) |

| 90+ | 6 (42.9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 2 (14.3) |

| Female | 12 (85.7) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 1 (7.1) |

| Married | 5 (35.7) |

| Widower/ Divorced | 8 (57.1) |

| Place of residence | |

| Home | 3 (21.4) |

| Nursing home | 11 (78.6) |

| (b) | |

| N (%) | |

| Age | |

| ≤49 | 3 (23.1) |

| 50–59 | 7 (53.8) |

| 60+ | 3 (23.1) |

| Relationship with care recipient | |

| Wife | 2 (14.3) |

| Daughter | 10 (71.4) |

| Son | 1 (7.1) |

| Godson | 1 (7.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 5 (38.5) |

| Married | 7 (53.8) |

| Education level | |

| Primary | 2 (15.4) |

| Secondary | 9 (69.2) |

| University | 2 (15.4) |

| Working status | |

| Unemployed | 1 (7.1) |

| Self-employed | 1 (7.1) |

| Housewife | 5 (35.7) |

| Employed | 7 (50) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, E.L.-Y.; Lau, J.Y.-C.; Chau, P.Y.-K.; Chung, R.Y.-N.; Wong, S.Y.-S.; Woo, J.; Yeoh, E.-K. Caregivers’ Experience of End-of-Life Stage Elderly Patients: Longitudinal Qualitative Interview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042101

Wong EL-Y, Lau JY-C, Chau PY-K, Chung RY-N, Wong SY-S, Woo J, Yeoh E-K. Caregivers’ Experience of End-of-Life Stage Elderly Patients: Longitudinal Qualitative Interview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042101

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Eliza Lai-Yi, Janice Ying-Chui Lau, Patsy Yuen-Kwan Chau, Roger Yat-Nork Chung, Samuel Yeung-Shan Wong, Jean Woo, and Eng-Kiong Yeoh. 2022. "Caregivers’ Experience of End-of-Life Stage Elderly Patients: Longitudinal Qualitative Interview" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042101

APA StyleWong, E. L.-Y., Lau, J. Y.-C., Chau, P. Y.-K., Chung, R. Y.-N., Wong, S. Y.-S., Woo, J., & Yeoh, E.-K. (2022). Caregivers’ Experience of End-of-Life Stage Elderly Patients: Longitudinal Qualitative Interview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042101