Prevalence, Risk Factors and Impacts Related to Mould-Affected Housing: An Australian Integrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A recent government inquiry into biotoxin-related illness reported impacts on health and economic well-being of occupants living in mould-affected housing [41].

2. Materials and Methods

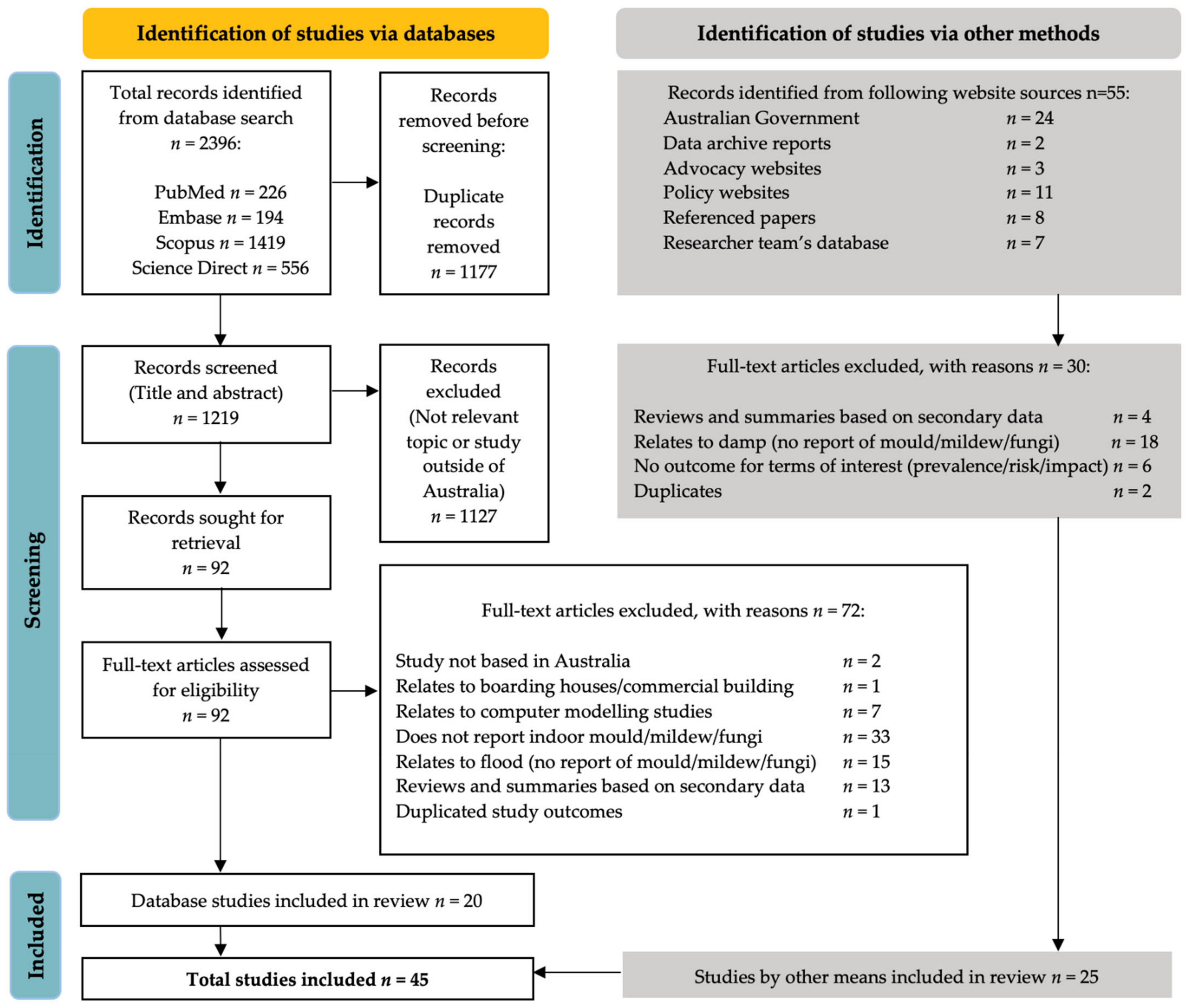

2.1. Literature Review Methodology

What is the current state of evidence on the prevalence, risk factors and impacts related to mould-affected housing in Australia?

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria and Quality Appraisal

2.3. Data Management and Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Profile of Included Literature

3.2. Study Topics Included in the Literature

3.3. Chronological Distribution of Included Literature

- The cessation of mould reporting by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- The investigation of indoor air quality in housing and biological data in relationship to health was mainly undertaken in the mid-1990s;

- There are three times more studies exploring socioeconomic factors/circumstance relating to housing conditions than that of epidemiological, clinical and health studies since 2007;

- As building regulations moved towards more energy efficient housing and bushfire housing safety requirements, building sciences, architecture, property, law and the building/mould industry start investigating interventions, defects and “root cause” of moisture-related building issues in built environment;

- There is a 22-year gap in capturing or reporting indoor mould in population-based housing studies. This may indicate an incorrect assumption, until relatively recently, that enhancements in building regulations had “fixed the problem” of mould in houses (and hence the perceived lack of need to collect this data). Alternatively, it may be an indication of the consequences of the funding restrictions placed on the data collection agency (and hence the inability to collect all of the data about housing that was previously funded).

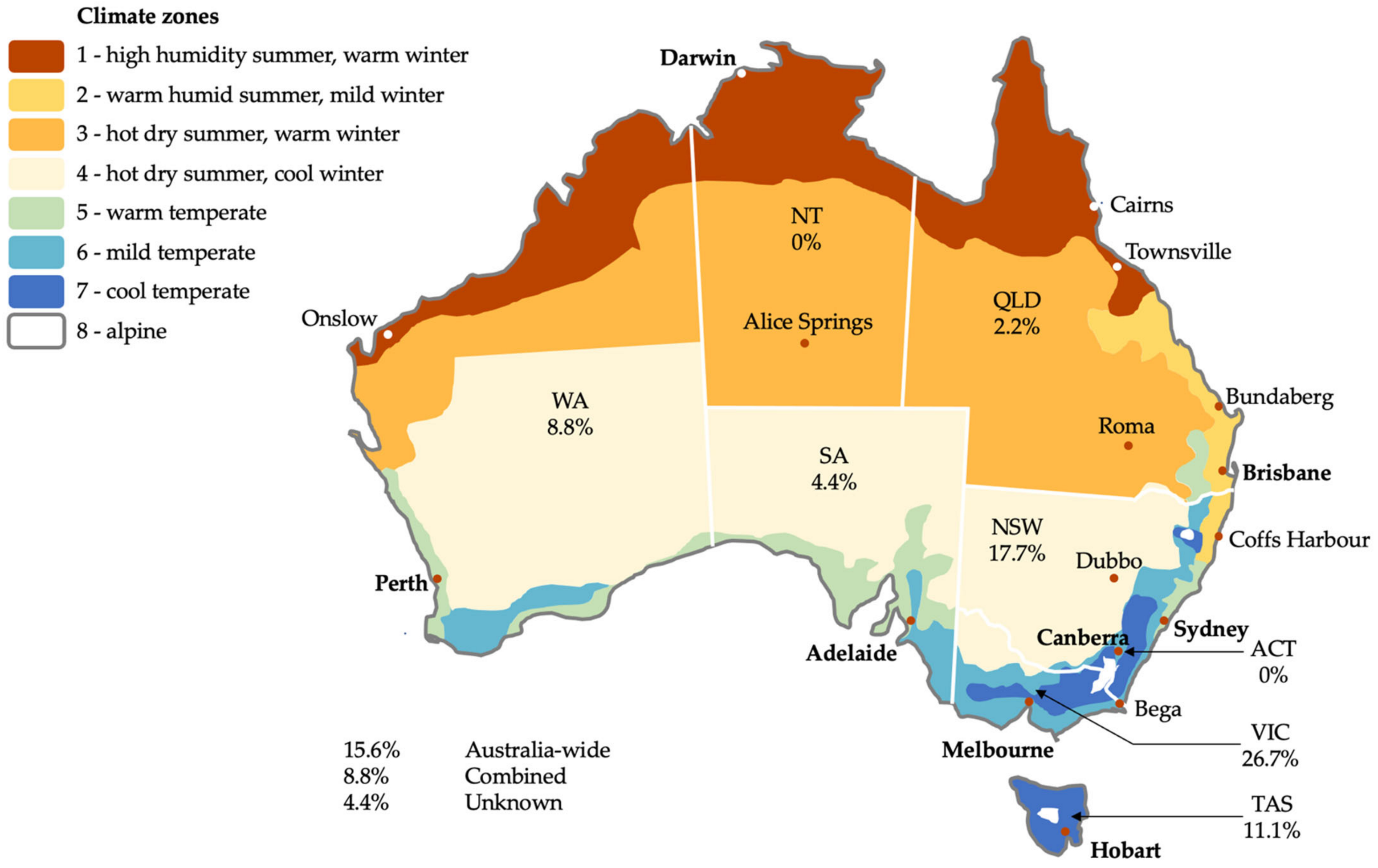

3.4. Geographical Location of Included Literature

4. Discussion

4.1. Climate and Risk of Indoor Mould

- Houses have subfloor ventilation and naturally ventilated roof spaces;

- The opening of windows to cool a home is common on warmer days;

- Residential buildings are not fully sealed or fully mechanically cooled or ventilated.

4.2. Housing Conditions and Risk of Indoor Mould

- The question does not allow for the variable “mould” in the answer?

- The variable is not statistically significant enough to be reported upon.

4.2.1. Housing Conditions, Rental Housing and Risk of Mould

4.2.2. Housing Conditions, COVID-19 Insights and Risk of Mould

4.3. Housing Conditions, Socioeconomic Circumstance and Risk of Mould

4.4. Building Characteristics and Risk of Mould

4.5. Occupant Behaviours and Risk of Mould

4.6. Prevalence of Indoor Mould Conditions in Australian Housing

4.7. Health Impacts Related to Reported Mould/Mildew/Fungi

4.8. Gaps and Implications for Research, Practice and Policy

- Implement national and climatical coverage of real-time data (temperature, available moisture, humidity) and “root cause” case study investigations for indoor mould in both older housing and code-compliant homes.

- Investigate the relationship between occupant behaviours, housing maintenance and the occurrence of indoor mould in poor-quality housing.

- Establish a national longitudinal housing condition survey that includes indoor mould, renovations and maintenance.

- To continue to use the question “Does this dwelling have any MAJOR building problems?” or similar in current longitudinal housing studies and report on the “mould” variable.

- Investigate the impact and characteristics of multiple-symptom health effects and their relationship to the biological components that are present in damp housing conditions.

“The precautionary principle, proposed as a new guideline in environmental decision making, has four central components: taking preventive action in the face of uncertainty; shifting the burden of proof to the proponents of an activity; exploring a wide range of alternatives to possibly harmful actions; and increasing public participation in decision making.”[125]

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Dampness and Mould. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/164348 (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Omebeyinje, M.H.; Adeluyi, A.; Mitra, C.; Chakraborty, P.; Gandee, G.M.; Patel, N.; Verghese, B.; Farrance, C.E.; Hull, M.; Basu, P.; et al. Increased prevalence of indoor: Aspergillus and penicillium species is associated with indoor flooding and coastal proximity: A case study of 28 moldy buildings. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2021, 23, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U. Prevalence of dampness and mold in European housing stock. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norbäck, D.; Zock, J.P.; Plana, E.; Heinrich, J.; Tischer, C.; Jacobsen Bertelsen, R.; Sunyer, J.; Künzli, N.; Villani, S.; Olivieri, M.; et al. Building dampness and mold in European homes in relation to climate, building characteristics and socio-economic status: The European community respiratory health survey ECRHS II. Indoor Air 2017, 27, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnbjornsdottir, M.I. Prevalence and incidence of respiratory symptoms in relation to indoor dampness: The RHINE study. Thorax 2006, 61, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornehag, C.G.; Sundell, J.; Sigsgaard, T. Dampness in buildings and health (DBH): Report from an ongoing epidemiological investigation on the association between indoor environmental factors and health effects among children in Sweden. Indoor Air 2004, 14, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sundell, J. On associations between housing characteristics, dampness and asthma and allergies among children in northeast Texas. Indoor Built Environ. 2013, 22, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkeley Lab. Prevalence of Building Dampness. Available online: https://iaqscience.lbl.gov/prevalence-building-dampness (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Ingham, T.; Keall, M.; Jones, B.; Aldridge, D.R.T.; Dowell, A.C.; Davies, C.; Crane, J.; Draper, J.B.; Bailey, L.O.; Viggers, H.; et al. Damp mouldy housing and early childhood hospital admissions for acute respiratory infection: A case control study. Thorax 2019, 74, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden-Chapman, P.; Matheson, A.; Crane, J.; Viggers, H.; Cunningham, M.; Blakely, T.; Cunningham, C.; Woodward, A.; Saville-Smith, K.; O’Dea, D.; et al. Effect of insulating existing houses on health inequality: Cluster randomised study in the community. BMJ 2007, 334, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa. One in Five Homes Damp. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/one-in-five-homes-damp (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Cai, J.; Liu, W.; Hu, Y.; Zou, Z.; Shen, L.; Huang, C. Associations between home dampness-related exposures and childhood eczema among 13,335 preschool children in Shanghai, China: A cross-sectional study. Environ. Res. 2016, 146, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Huang, C.; Hu, Y.; Zou, Z.; Shen, L.; Sundell, J. Associations of building characteristics and lifestyle behaviors with home dampness-related exposures in Shanghai dwellings. Build. Environ. 2015, 88, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Li, B.; Yu, W.; Wang, H.; Du, C.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Deng, Q.; Yang, X.; et al. Household dampness-related exposures in relation to childhood asthma and rhinitis in China: A multicentre observational study. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinmayr, G.; Gehring, U.; Genuneit, J.; Büchele, G.; Kleiner, A.; Siebers, R.; Wickens, K.; Crane, J.; Brunekreef, B.; Strachan, D.P. Dampness and moulds in relation to respiratory and allergic symptoms in children: Results from phase two of the international study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC phase two). Clin. Exp. Allergy 2013, 43, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswathy, M.; Venugopal, V.; Kindo, A.J.; Thyagarajan, R. Housing characteristics in developing countries as important determinants of household indoor dampness and mould. Indian J. Environ. Prot. 2019, 39, 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Prapamontol, T.; Norbäck, D.; Thongjan, N.; Suwannarin, N.; Somsunun, K.; Ponsawansong, P.; Khuanpan, T.; Kawichai, S.; Naksen, W. Associations between indoor environment in residential buildings in wet and dry seasons and health of students in upper northern Thailand. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 2252–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board, B.C.; Dewsbury, M.; Law, T.; Potgieter, J.; Fitz-Gerald, D.; Mccomish, B.; Chandler, T.; Soudan, A. Scoping Study of Condensation in Residential Buildings—Appendix. Available online: https://www.abcb.gov.au/sites/default/files/resources/2020//Scoping_Study_of_Condensation_in_Residential_Buildings_Appendices.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Major, J.L.; Boese, G.W. Cross section of legislative approaches to reducing indoor dampness and mold. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2017, 23, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfar-Barnard, L.; Bennett, J.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Jacobs, D.E.; Ormandy, D.; Cutler-Welsh, M.; Preval, N.; Baker, M.G.; Keall, M. Measuring the effect of housing quality interventions: The case of the New Zealand “Rental warrant of fitness”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Lester, L.; Beer, A.; Bentley, R. An Australian geography of unhealthy housing. Geogr. Res. 2019, 57, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R.A.; Taylor, T.; Fleming, L.E.; Morrissey, K.; Morris, G.; Wigglesworth, R. Making the case for “Whole system” Approaches: Integrating public health and housing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keall, M.; Baker, M.G.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Cunningham, M.; Ormandy, D. Assessing housing quality and its impact on health, safety and sustainability. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2010, 64, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, W.J. Review of some effects of climate change on indoor environmental quality and health and associated no-regrets mitigation measures. Build. Environ. 2015, 86, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antova, T.; Pattenden, S.; Brunekreef, B.; Heinrich, J.; Rudnai, P.; Forastiere, F.; Luttmann-Gibson, H.; Grize, L.; Katsnelson, B.; Moshammer, H. Exposure to indoor mould and children’s respiratory health in the PATY study. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2008, 62, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlimann, A.C.; Warren-Myers, G.; Browne, G.R. Is the australian construction industry prepared for climate change? Build. Environ. 2019, 153, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, K.; Charles-Guzman, K.; Wheeler, K.; Abid, Z.; Graber, N.; Matte, T. Health effects of coastal storms and flooding in urban areas: A review and vulnerability assessment. J. Environ. Public Health 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardoulakis, S.; Dimitroulopoulou, C.; Thornes, J.; Lai, K.-M.; Taylor, J.; Myers, I.; Heaviside, C.; Mavrogianni, A.; Shrubsole, C.; Chalabi, Z.; et al. Impact of climate change on the domestic indoor environment and associated health risks in the UK. Environ. Int. 2015, 85, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencastro, J.; Fuertes, A.; Fox, A.; de Wilde, P. The impact of defects on energy performance of buildings: Quality management in social housing developments. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 4357–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price Waterhouse Coopers (PwC). Department of Building and Housing: Weathertightness—Estimating the Cost. Available online: https://www.interest.co.nz/sites/default/files/PWC-leakyhomesreport.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Richardson, B.A. Defects and Deterioration in Buildings, 2nd ed.; Spon Press: London, UK, 2001; ISBN 041925210X. [Google Scholar]

- Paevere, P.; Nguyen, M. Nailplate backout—Is it a problem in plated timber trusses? In Proceedings of the 10th World Conference on Timber Engineering, Miyazaki, Japan, 2–5 June 2008; Volume 3, pp. 1191–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Mainey, A.; Gilbert, B.P.; Redman, A.; Gunalan, S.; Bailleres, H. Time dependent moisture driven backout of nailplates: Experimental investigations and numerical predictions. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2021, 79, 1589–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox-Ganser, J.M. Indoor dampness and mould health effects—Ongoing questions on microbial exposures and allergic versus nonallergic mechanisms. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 1478–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, W.J.; Eliseeva, E.A.; Mendell, M.J. Association of residential dampness and mold with respiratory tract infections and bronchitis: A meta-analysis. Environ. Health 2010, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendell, M.J.; Mirer, A.G.; Cheung, K.; Tong, M.; Douwes, J. Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness-related agents: A review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thacher, J.D.; Gruzieva, O.; Pershagen, G.; Melén, E.; Lorentzen, J.C.; Kull, I.; Bergström, A. Mold and dampness exposure and allergic outcomes from birth to adolescence: Data from the BAMSE cohort. Allergy 2017, 72, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, E.; Lester, L.H.; Bentley, R.; Beer, A. Poor housing quality: Prevalence and health effects. J. Prev. Interv. Commun. 2016, 44, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewsbury, M.; Law, T.; Potgieter, J.; Fitz-Gerald, D.; McComish, B.; Chandler, T.; Soudan, A. Scoping Study of Condensation in Residential Buildings: Final Report (23 September 2016) (for the Australian Building Codes Board). 2016. Available online: https://www.abcb.gov.au/sites/default/files/resources/2020/Scoping_Study_of_Condensation_in_Residential_Buildings.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Garrett, M.H.; Rayment, P.R.; Hooper, M.A.; Abramson, M.J.; Hooper, B.M. Indoor airborne fungal spores, house dampness and associations with environmental factors and respiratory health in children. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1998, 28, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commonwealth of Australia. House of representatives standing committee on health aged care and sport. In Report on the Inquiry into Biotoxin-Related Illnesses in Australia; Parliament of Australia: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2018. Available online: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportrep/024194/toc_pdf/ReportontheInquiryintoBiotoxin-relatedIllnessesinAustralia.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Dewsbury, M.; Law, T.; Henderson, A.D. Investigation of Destructive Condensation in Australian Cool-Temperate Buildings: Final Report. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301894751_Final_report_-_Investigation_of_destructive_condensation_in_Australian_cool-temperate_buildings (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Brambilla, A.; Gasparri, E. Mould growth models and risk assessment for emerging timber envelopes in Australia: A comparative study. Buildings 2021, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, A.; Gasparri, E. Hygrothermal behaviour of emerging timber-based envelope technologies in australia: A preliminary investigation on condensation and mould growth risk. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.; Dewsbury, M.; Douwes, J. Has a singular focus of building regulations created unhealthy homes. Arch. Sci. Rev. 2019, 63, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Daniel, L. Rental Insights: A COVID-19 Collection. Available online: https://www.ahuri.edu.au/sites/default/files/migration/documents/Rental-Insights-A-COVID-19-Collection.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Choice; National Shelter; The National Assoication of Tenant Organisations (NATO); Martin, C. Disrupted: The Consumer Experience of Renting in Australia. Available online: https://www.shelterwa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Disrupted-2018ReportbyCHOICENationalShelterandNATO.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Andersen, M.J.; Williamson, A.B.; Fernando, P.; Wright, D.; Redman, S. Housing conditions of urban households with aboriginal children in NSW Australia: Tenure type matters. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Measuring the Impacts of COVID-19, Mar–May 2020. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/measuring-impacts-covid-19-mar-may-2020 (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, July 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/household-impacts-covid-19-survey/latest-release#emotional-and-mental-wellbeing (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Noble, H.; Smith, J. Reviewing the literature: Choosing a review design. Evid. Based Nurs. 2018, 21, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C. An overview of the integrative research review. Prog. Transplant. 2005, 15, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toronto, C.E.; Remington, R. A Step-by-Step Guide to Conducting an Integrative Review, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-37504-1. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, L.; Takahashi, R. A Resource for Developing an Evidence Synthesis Report for Policy-Making. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK453541/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK453541.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018, User Guide. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Tyndall, J. AACODS Checklist for Appraising Grey Literature. Available online: https://dspace.flinders.edu.au/xmlui/bitstream/handle/2328/3326/AACODS_Checklist.pdf;jsessionid=A9241274C90700E1A8E77D8534BC8788?sequence=4 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Bower, M.; Buckle, C.; Rugel, E.; Donohoe-Bales, A.; McGrath, L.; Gournay, K.; Barrett, E.; Phibbs, P.; Teesson, M. ‘Trapped’, ‘anxious’ and ‘traumatised’: COVID-19 intensified the impact of housing inequality on Australians’ mental health. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2021, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choice; National Shelter. Unsettled: Life in Australia’s Private Rental Market. 2016. Available online: http://shelter.org.au/site/wp-content/uploads/The-Australian-Rental-Market-Report-Final-Web.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Johnston, S.C.; Staines, D.R.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S.M. Epidemiological characteristics of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis in Australian patients. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 8, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4182.0—Housing Characteristics, Costs and Conditions, Australia, 1994; Commonwealth of Australia; 1996; pp. 1–66. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4182.01994?OpenDocument (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Victorian Council of Social Service (VCOSS). Decent Not Dodgy. “Secret Shopper” Survey. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2010-07/apo-nid22132.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Matheson, M.; Abramson, M.J.; Dharmage, S.C.; Forbes, A.B.; Raven, J.M.; Thien, F.C.K.; Walters, E.H. Changes in indoor allergen and fungal levels predict changes in asthma activity among young adults. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2005, 35, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmage, S.; Bailey, M.; Raven, J.; Abeyawickrama, K.; Cao, D.; Guest, D.; Rolland, J.; Forbes, A.; Thien, F.; Abramson, M.; et al. Mouldy houses influence symptoms of asthma among atopic individuals. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2002, 32, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmage, S.; Bailey, M.; Raven, J.; Mitakakis, T.; Cheng, A.; Guest, D.; Rolland, J.; Forbes, A.; Thien, F.; Abramson, M.; et al. Current indoor allergen levels of fungi and cats, but not house dust mites, influence allergy and asthma in adults with high dust mite exposure. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Robertson, H.J. Built form and health. Indoor Environ. 1992, 1, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmage, S.; Bailey, M.; Raven, J.; Cheng, A.; Rolland, J.; Thien, F.; Forbes, A.; Abramson, M.; Walters, E.H. Residential characteristics influence der p 1 levels in homes in Melbourne, Australia. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1999, 29, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmage, S.; Bailey, M.; Raven, J.; Mitakakis, T.; Thien, F.; Forbes, A.; Guest, D.; Abramson, M.; Walters, E.H. Prevalence and residential determinants of fungi within homes in Melbourne, Australia. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1999, 29, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, M.H.; Hooper, B.M.; Hooper, M.A. Indoor environmental factors associated with house-dust-mite allergen (der p 1) levels in south-eastern Australian houses. Allergy 1998, 53, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godish, D.; Godish, T.; Hooper, B.; Hooper, M.; Cole, M. Airborne mould levels and related environmental factors in Australian houses. Indoor Built Environ. 1996, 5, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willand, N.; Maller, C.; Ridley, I. Addressing health and equity in residential low carbon transitions—Insights from a pragmatic retrofit evaluation in Australia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 53, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalar, P.; Novak, M.; de Hoog, G.S.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Dishwashers—A man-made ecological niche accommodating human opportunistic fungal pathogens. Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crommelin, L.; Thompson, S.; Easthope, H.; Loosemore, M.; Yang, H.; Buckle, C.; Randolph, B. Cracks in the Compact City: Tackling Defects in Multi-Unit Strata Housing. Final Project Report. 2021. Sydney, Australia. Available online: https://cityfutures.ada.unsw.edu.au//research/projects/defects-strata/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Kempton, L.; Kokogiannakis, G.; Cooper, P. Mould risk evaluations in residential buildings via site audits and longitudinal monitoring. Build. Environ. 2021, 191, 107584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihrshahi, S.; Marks, G.; Vanlaar, C.; Tovey, E.; Peat, J. Predictors of high house dust mite allergen concentrations in residential homes in Sydney. Allergy 2002, 57, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, D.H.; Rogers, P. Allergic alveolitis due to wood-rot fungi. Allergy Proc. 1991, 12, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.J.; Williamson, A.B.; Fernando, P.; Redman, S.; Vincent, F. “There’s a housing crisis going on in Sydney for aboriginal people”: Focus group accounts of housing and perceived associations with health. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.J.; Skinner, A.; Williamson, A.B.; Fernando, P.; Wright, D. Housing conditions associated with recurrent gastrointestinal infection in urban aboriginal children in NSW, Australia: Findings from SEARCH. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2018, 42, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, S.; Pignatta, G.; Paolini, R.; Synnefa, A.; Santamouris, M. An extensive study on the relationship between energy use, indoor thermal comfort, and health in social housing: The case of the New South Wales, Australia. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Bari, Italy, 1 September 2019; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 609, p. 042067. [Google Scholar]

- Mészáros, D.; Burgess, J.; Walters, E.H.; Johns, D.; Markos, J.; Giles, G.; Hopper, J.; Abramson, M.; Dharmage, S.C.; Matheson, M. Domestic airborne pollutants and asthma and respiratory symptoms in middle age. Respirology 2014, 19, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsonby, A.-L.; Couper, D.; Dwyer, T.; Carmichael, A.; Kemp, A.; Cochrane, J. The relation between infant indoor environment and subsequent asthma. Epidemiology 2000, 11, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper, D.; Ponsonby, A.L.; Dwyer, T. Determinants of dust mite allergen concentrations in infant bedrooms in Tasmania. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1998, 28, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, T.; Dewsbury, M. The unintended consequence of building sustainably in Australia. In Sustainable Development Research in the Asia-Pacific Region. World Sustainability Series; Leal, F.W., Rogers, J., Iyer-Raniga, U., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 525–547. ISBN 978-3-319-73293-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Spickett, J.; Lee, A.H.; Rumchev, K.; Stick, S. Household hygiene practices in relation to dampness at home and current wheezing and rhino-conjunctivitis among school age children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2005, 16, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midson, W.; Cheong, C.; Neumeister-Kemp, H.; White, K. Indoor air quality problems as a result of installing split system HVAC units in mass housing accommodations. In Proceedings of the 10th International Healthy Buildings Conference, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 8–13 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, C.; Neumeister-Kemp, H.G.; Kemp, P.C. Hot water extraction in carpeted homes in western Australia: Effect on airborne fungal spora. In Proceedings of the 14th International Union of Air Pollution Prevention and Environmental Protection Associations (IUAPPA) World Congress 2007, 18th Clean Air Society of Australia and New Zealand (CASANZ) Conference, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 9–13 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, C.D.; Neumeister-Kemp, H.G.; Dingle, P.W.; Hardy, G.S.J. Intervention study of airborne fungal spora in homes with portable HEPA filtration units. J. Environ. Monit. 2004, 6, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziersch, A.; Walsh, M.; Due, C.; Duivesteyn, E. Exploring the relationship between housing and health for refugees and asylum seekers in south Australia: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziersch, A.; Due, C.; Walsh, M.; Arthurson, K. Belonging Begins at Home: Housing, Social Inclusion and Health and Wellbeing for People from Refugee and Asylum Seeking Backgrounds; Flinders Press: Bedford Park, SA, Australia, 2017; ISBN 9780648146018. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, K.K.; Chang, A.B.; Anderson, J.; Arnold, D.; Goyal, V.; Dunbar, M.; Otim, M.; O’Grady, K.-A.F. The incidence and short-term outcomes of acute respiratory illness with cough in children from a socioeconomically disadvantaged urban community in Australia: A community-based prospective cohort study. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, H.J. Spatial characteristics of southeast australian housing linked with allergic complaint. Build. Environ. 2001, 36, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Daniel, L.; Bentley, R.; Pawson, H.; Stone, W.; Rajagopalan, P.; Hulse, K.; Beer, A.; London, K.; Zillante, G.; et al. The Australian Housing Conditions Dataset: Technical Report; The University of Adelaide—Healthy Cities Research: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2018; pp. 1–28. Available online: https://dataverse.ada.edu.au/file.xhtml?fileId=9876&version=1.0 (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Johnston, N.; Reid, S. An Examination of Building Defects in Residential Multi-Owned Properties. Available online: https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/831217/Examining-Building-Defects-Research-Report-S-Reid-N-Johnston.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Saltos, N.; Saunders, N.A.; Bhagwandeen, S.B.; Jarvie, B. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis in a mouldy house. Med. J. Aust. 1982, 2, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S. ANRES: A Snapshot of Living with Environmental Sensitivities in Australia in 2019. Available online: https://anres.org/2019-anres-data-update/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Trewin, D. Australian Housing Survey—Housing Characteristics, Costs and Conditions, Cat No. 4182.0. 1999. Available online: https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/D9B696BEE455C74CCA2569890002D180/$File/41820_1999.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Law, T. An increasing resistance to increasing resistivity. Arch. Sci. Rev. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABCB. Handbook: Condensation in Buildings. Available online: https://www.abcb.gov.au/sites/default/files/resources/2020//Handbook_Condensation_in_Buildings_2019.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 1301.0-Year Book Australia, 2004: How Many People Live in Australia’s Coastal Areas? Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/previousproducts/1301.0feature%20article32004 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Adams, R.I.; Bhangar, S.; Dannemiller, K.C.; Eisen, J.A.; Fierer, N.; Gilbert, J.A.; Green, J.L.; Marr, L.C.; Miller, S.L.; Siegel, J.A.; et al. Ten questions concerning the microbiomes of buildings. Build. Environ. 2016, 109, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendell, M.J.; Macher, J.M.; Kumagai, K. Measured moisture in buildings and adverse health effects: A review. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Meteorology (BOM). Average 9am and 3pm Relative Humidity. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/jsp/ncc/climate_averages/relative-humidity/index.jsp (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Brambilla, A.; Sangiorgio, A. Mould growth in energy efficient buildings: Causes, health implications and strategies to mitigate the risk. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2020, 132, 110093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Beer, A.; Zillante, G.; London, K.; Bentley, R.; Hulse, K.; Pawson, H.; Randolph, B.; Stone, W.; Rajagopolan, P. Housing Questionnaire June 2016: 1 ADA.Questionnaire.01422. Available online: https://dataverse.ada.edu.au/file.xhtml?fileId=9875&version=1.0 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Home Ownership and Housing Tenure. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/home-ownership-and-housing-tenure (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Braubach, M.; Jacobs, D.E.; Ormandy, D. Environmental Burden of Disease Associated with Inadequate Housing: Methods for Quantifying Health Impacts of Selected Housing Risks in the WHO European Region. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/142077/e95004.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Kanchongkittiphon, W.; Mendell, M.J.; Gaffin, J.M.; Wang, G.; Phipatanakul, W. Indoor environmental exposures and exacerbation of asthma: An update to the 2000 review by the institute of medicine. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, T.; Stanojevic, S.; Moores, G.; Gershon, A.S.; Bateman, E.D.; Cruz, A.A.; Boulet, L.-P. Global asthma prevalence in adults: Findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). National Asthma Indicators—An Interactive Overview. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/asthma-monitoring-based-on-current-indicators/contents/indicators/indicator-10-costs-of-asthma (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Asthma. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/asthma/contents/asthma (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Gasparri, E.; Brambilla, A.; Aitchison, M. Hygrothermal analysis of timber-based external walls across different Australian climate zones. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering, Seoul, Korea, 20–23 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, S.; Dewsbury, M.; Watson, P.; Lovell, H. A Bio-hygrothermal analysis of typical australian residential wall systems. In Proceedings of the 54th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association (ANZAScA), Auckland, New Zealand, 26 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla, A.; Gasparri, E.; Aitchison, M. Building with timber across australian climatic contexts: A hygrothermal analysis. In Proceedings of the 52nd International Conference of the Architectural Science Association (ANZAScA), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 28 November–1 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dewsbury, M.; Law, T.; Henderson, A.D. Investigation of Destructive Condensation in Australian Cool Temperate Buildings Appendix 1: Case Study House 1. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301895039_Investigation_of_destructive_condensation_in_Australian_cool-temperate_buildings_Appendix_1 (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Dewsbury, M.; Law, T.; Henderson, A.D. Investigation of Destructive Condensation in Australian Cool Temperate Buildings Appendix 2: Case Study House 2. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301894762_Investigation_of_destructive_condensation_in_Australian_cool-temperate_buildings_Appendix_2 (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Dewsbury, M.; Law, T.; Henderson, A.D. Investigation of Destructive Condensation in Australian Cool Temperate Buildings Appendix 3: Case Study House 3. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301894764_Investigation_of_destructive_condensation_in_Australian_cool-temperate_buildings_Appendix_3 (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; AlWaer, H.; Omrany, H.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Alalouch, C.; Clements-Croome, D.; Tookey, J. Sick building syndrome: Are we doing enough? Archit. Sci. Rev. 2018, 61, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuuminen, T.; Lohi, J. Immunological and toxicological effects of bad indoor air to cause dampness and mold hypersensitivity syndrome. AIMS Allergy Immunol. 2018, 2, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuuminen, T. The roles of autoimmunity and biotoxicosis in sick building syndrome as a “starting point” for irreversible dampness and mold hypersensitivity syndrome. Antibodies 2020, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, R.C.; House, D.; Ryan, J.C. Structural brain abnormalities in patients with inflammatory illness acquired following exposure to water-damaged buildings: A volumetric MRI study using neuroquant®. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2014, 45, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, C.; Pahl, S.; Jones, R.V.; Fuertes, A. “Damp in bathroom. damp in back room. It’s very depressing!” exploring the relationship between perceived housing problems, energy affordability concerns, and health and well-being in UK social housing. Energy Policy 2017, 106, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R.A.; Le Cocq, K.; Nikolaou, V.; Osborne, N.J.; Thornton, C.R. Identifying risk factors for exposure to culturable allergenic moulds in energy efficient homes by using highly specific monoclonal antibodies. Environ. Res. 2016, 144, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrubsole, C.; Macmillan, A.; Davies, M.; May, N. 100 unintended consequences of policies to improve the energy efficiency of the UK housing stock. Indoor Built Environ. 2014, 23, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braubach, M.; Savelsberg, J.; Social Inequalities and Their Influence on Housing Risk Factors and Health. A Data Report Based on the WHO LARES Database. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/113260/E92729.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Housing and Health Guidelines. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550376 (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Kriebel, D.; Tickner, J.; Epstein, P.; Lemons, J.; Levins, R.; Loechler, E.L.; Quinn, M.; Rudel, R.; Schettler, T.; Stoto, M. The precautionary principle in environmental science. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Grey Literature | Agency/Group | Website Link |

|---|---|---|

| Australian Government | Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) | www.abs.gov.au/ (accessed on 1 November 2021). |

| Australian Institute of Health Welfare (AIHW) | www.aihw.gov.au/ (accessed on 18 November 2021). | |

| Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) | www.abcb.gov.au (accessed on 5 November 2021). | |

| Data Archive | Australian Data Archive (ADA) | www.dataverse.ada.edu.au/ (accessed on 4 November 2021). |

| Advocacy websites | Housing advocacy group | www.shelter.org.au/ (accessed on 19 November 2021). |

| Environmental sensitivities advocacy group | www.anres.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2021). | |

| Policy websites | Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) | www.ahuri.edu.au/ (accessed on 8 November 2021). |

| Analysis, Policy & Observatory | www.apo.org.au/ (accessed on 1 November 2021). |

| Place | Mould | Housing | Risk/Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Mould | Hous *, House, Housing | Health |

| Fungi | Indoor | Well-being, Well-being | |

| Mildew | Home * | Cost * | |

| Condensation | Dwelling * | Impact * | |

| Flood * | Residen * | Hardship * | |

| “Water damage” | Residential | Economic * | |

| “Water damage” | Residence | Financial | |

| Damp * | Building * | Risk * | |

| Perception * |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Australian residential dwelling (detached and semi-detached single family homes, townhouses, units/apartments) | Houses or studies not based in Australia. Boarding houses or commercial buildings |

| Occupants (all ages), expert opinions or housing data (including biological) | Building computer modelling studies |

| Reports indoor mould/mildew/fungi | Does not report indoor mould/mildew/fungi |

| Data/information quantitative, qualitative, case studies relating to prevalence, risk factors or impact and reported indoor mould/mildew/fungi | No data or unclear outcome relating to prevalence, risk factors or impact for reported indoor mould/mildew/fungi |

| Any study design providing original data on housing conditions/occupants experiences or housing condition data from defects or insurance claims that are publicly available | Reviews and summaries based on secondary data |

| Full text available | Full text not available |

| Study Details | Study Categories | n (%) | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical distribution | Australia-wide | 7 (15.6%) | [39,46,47,57,58,59,60] | |

| Victoria (VIC) | 12 (26.7%) | [40,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71] | ||

| New South Wales (NSW) | 8 (17.7%) | [48,72,73,74,75,76,77,78] | ||

| Tasmania (TAS) | 5 (11.1%) | [42,79,80,81,82] | ||

| Western Australia (WA) | 4 (8.8%) | [83,84,85,86] | ||

| South Australia (SA) | 2 (4.4%) | [87,88] | ||

| Queensland (QLD) | 1 (2.2%) | [89] | ||

| Australian Capital Territory (ACT) | ||||

| Northern Territory (NT) | ||||

| Combinations: (VIC, TAS, NSW, QLD, SA, WA) | 4 (8.8%) | [41,90,91,92] | ||

| Unknown | 2 (4.4%) | [93,94] | ||

| Quantitative Non-randomised Studies 18 (40%) | Cohort Studies | 8 (17.8%) | [48,62,63,64,77,79,80,89] | |

| Cross-Sectional Studies | 7 (15.6%) | [66,67,68,69,74,81,83] | ||

| Case Control (houses) | 2 (4.4%) | [85,86] | ||

| Intervention Study (houses) | 1 (2.2%) | [84] | ||

| Quantitative Descriptive Studies 18 (40%) | Prevalence Studies | 8 (17.8%) | [46,47,58,61,65,71,90,94] | |

| Case Series (houses) | 3 (6.7%) | [42,73,82] | ||

| Cohort Studies | 3 (6.7%) | [40,59,78] | ||

| Cross-Sectional | 2 (4.4%) | [91,95] | ||

| Case Report (human) | 1 (2.2%) | [93] | ||

| Case Control (human) | 1 (2.2%) | [75] | ||

| Mixed Methods Studies 5 (11.1%) | Mixed Methods Studies | 2 (4.4%) | [57,70] | |

| Building Industry Reports | 3 (6.7%) | [39,72,92] | ||

| Qualitative Descriptive Studies 4 (8.9%) | Qualitative Descriptive Studies | 3 (6.7%) | [76,87,88] | |

| Government Inquiry Report | 1 (2.2%) | [41] | ||

| Study quality appraisal | Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, Significance Checklist (AACODS) n = 16 | n (%) | n (%) | Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT) n = 45 |

| * | ||||

| ** | 1 (6.3%) | 2 (4.4%) | * | |

| *** | 1 (2.2%) | ** | ||

| **** | 6 (13.3%) | *** | ||

| ***** | 1 (6.3%) | 15 (33.3%) | **** | |

| ****** | 14 (87.5%) | 21 (46.7%) | ***** | |

| Study Topics | Number (n = 45) n (%) | Subtopics | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building characteristics | 19 (42.2%) | Indoor biological data | [66,67,68,69,74,81] |

| Housing survey data | [60,91] | ||

| Housing defects and “root cause” | [39,42,72,73,82,92] | ||

| Indoor mould intervention | [70,71,84,85,86] | ||

| Health | 14 (31.1%) | Asthma, allergy, respiratory | [40,62,63,64,79,80,89] |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | [93] | ||

| Allergic alveolitis | [75] | ||

| Other | [41,59,65,90,94] | ||

| Housing conditions and socio-economic factors | 9 (20%) | Energy use and health | [78] |

| Health | [76,77,87,88] | ||

| Tenure | [47,48,58,61] | ||

| COVID-19 insights and housing conditions | 2 (4.4%) | Mental health | [57] |

| Renting | [46] | ||

| Occupant behaviours | 1 (2.2%) | Hygiene practices and health | [83] |

| Coverage of Climate Zones | Housing Conditions (n = 12) | Building Characteristics (n = 18) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Ref | n (%) | Ref | |

| All climate zones | 1 (5.6%) | [39] | ||

| 1—High humidity summer, warm winter | ||||

| 2—Warm humid summer, mild winter | ||||

| 3—Hot dry summer, warm winter | ||||

| 4—Hot dry summer, cool winter | ||||

| 5—Warm temperate | 1 (5.6%) | [75] | ||

| 5/6—Warm/mild temperate | 2 (16.7%) | [77,78] | 3 (16.7%) | [72,73,74] |

| 6—Mild temperate | 3 (25%) | [48,61,76] | 6 (33.3%) | [40,65,66,67,68,69] |

| 7—Cool temperate | 3 (16.7%) | [42,81,82] | ||

| 8—Alpine | ||||

| Unspecified study locations | 7 (58.3%) | [46,47,57,58,87,88,91] | 4 (22.2%) | [41,60,90,92] |

| Categories | Climate Zone | Risk Factors for Residential Indoor Mould/Mildew/Fungi | Level of Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor conditions | 5/6 | Hot walls compared to cooler room [73] | Y |

| 5/6 | Bedroom relative humidity levels RH > 80% [73] | Y | |

| 6 | High indoor humidity RH > 60% [40] | Y * | |

| 6 | RH equal > 70% [69] | Y * |

| Categories | Data Before 2002 | Data After 2003 | Risk Factors for Residential Indoor Mould/Mildew/Fungi | Level of Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing conditions | ||||

| Housing conditions | x | Poor housing conditions [75] | Y * | |

| x | Age of home >20 years (1992) [69], >10 years (1994) [60], >70 years (in 1991) [75] | Y *, Y, Y * | ||

| x | x | Leaking roof/ceiling [60], water intrusion [40,69], leaks [73] | Y, Y *, PY | |

| x | Water-damaged/collapsing wooden floorboards [75], cracks in cladding [40] | Y *, Y * | ||

| Building characteristics—Building, design, construction | ||||

| Construction | x | Exposing building materials to moisture during construction [41] | PY | |

| x | Building defects (various water/moisture/waterproofing related) [41,72,92] | PY, Y | ||

| Building envelope | x | Air-tightness in buildings, surface/interstitial condensation, thermal bridging, non-breathable wall wraps/foil wraps, unventilated walls [39,41,42,82,113,114,115] | PY, Y | |

| x | Use of timber framing and/or gypsum board [41] | PY | ||

| x | External walls adjoining unheated spaces [42,82,113,114,115] | Y | ||

| Roof | x | Blocked gutters/incorrect gutter installation [41] | PY | |

| Walls | x | Brick veneer [60] | Y | |

| x | Double brick [60,67] | Y *, Y | ||

| Foundation | x | Stumps [40] | Y * | |

| Drainage | x | Inappropriate external drainage [73] | PY | |

| Insulation | x | x | Limited or poorly installed insulation [49] | Y *, Y |

| Building layout | x | Higher number of bedrooms or bathrooms [90] | Y | |

| x | Airflow from bathrooms towards bedrooms [65,90] | Y | ||

| x | Inadequate building orientation and lack of breezes [65,90] | Y | ||

| Windows | x | Single glazed windows [70] | Y | |

| x | Poorly ventilated areas behind curtains [70] | Y | ||

| x | Lack of natural light [73] | PY | ||

| x | Limited ventilation through open windows [40] | Y * | ||

| Cooling/heating | x | Split-system air-conditioning units [41,84] | Y, PY | |

| x | No solid fuel fire [67] | Y * | ||

| x | Cold bedrooms [40] | Y * | ||

| Ventilation/air flow | x | x | Inadequate ventilation [41,73,83,92] | PY, Y, Y * |

| x | No bedroom ceiling fan, no kitchen exhaust fan, few extractor fans in wet areas [67] | Y * | ||

| non-structural | x | Carpets without professional cleaning [85] | Y | |

| x | Old carpets: 5 years or older [67] | Y * | ||

| Categories | Data Before 2002 | Data After 2003 | Risk Factors for Residential Indoor Mould/Mildew/Fungi | Level of Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupant behaviours | ||||

| Ventilation | x | Windows left open [67] | Y * | |

| x | Occupant unaware of their behaviours with condensation [39] | PY | ||

| x | Occupant reluctant to open windows and doors due to energy costs [39] | PY | ||

| x | Infrequent use of opening windows [40], infrequent natural ventilation [67] | Y * | ||

| x | Lack of opening windows [40] | Y * | ||

| Cleaning | x | Unclean plastic seals on a dishwasher doors [71] | Y * | |

| x | Failure to remove indoor mould growth [40] | Y * | ||

| x | Homes cleaned less [83], vacuuming > 1 week ago [67] | Y * | ||

| Pets | x | Presence of 1 cat or presence of 1 dog [67] | Y * | |

| Symptom/Illness | Sufficient Evidence for an Association by World Health Organization (WHO) [1] | Association | (n = 45) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Asthma in children [40] | Y * | 12 (26.7%) |

| Asthma [65,90] | Qual | ||

| Current asthma [79] | Y ** | ||

| Greater odds for an asthma attack in the last 12 months [62] | Y * | ||

| Increase in Peak Flow Variability (PFV) in asthmatics sensitised to fungi [63] | Y * | ||

| Exacerbation of asthma [76] | Qual | ||

| Wheeze | Wheeze [79] | Y ** | |

| Increase in wheeze [62] | Y | ||

| Cough | Cough [65,90] | Qual | |

| Respiratory | Acute respiratory illness with cough (ARIwC) in children [89] | Y | |

| Respiratory symptoms in children [40] | Y * | ||

| Respiratory problems/conditions [76,87] | Qual | ||

| Nocturnal chest tightness [79] | Y ** | ||

| Increased bronchial hyperreactivity (BHR) [64] | Y * | ||

| Clinical | Domestic allergic alveolitis [75] | Y * | |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis [93] | Y | ||

| Other symptom(s)/illness presentation | |||

| Allergy | Allergy in children [40] | Y * | 7 (15.6%) |

| Increase in allergy to fungi [62] | Y | ||

| Protective—Lower risk of allergy to fungi [64] | Y | ||

| Pollen and dust mite allergy [90] | Qual | ||

| Atopy | Atopy in children [40] | Y * | |

| Increase in atopy [62] | Y * | ||

| Gastrointestinal | Gastrointestinal infections in children [77] | Y * | |

| Mood/depression | Depression [57] | Y | |

| Sadness/depression [87] | Qual | ||

| Pain | Joint pain [87,90] | Qual | |

| Multiple-symptom presentation | |||

| Comorbidity | Biotoxin illness reported with multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS) [94] | Y | 5 (11.1%) |

| Biotoxin illness reported with tick-borne illness [94] | Y | ||

| ME/CFS | Moulds as a trigger for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) [59] | Y | |

| Biotoxin illness reported with ME/CFS [94] | Y | ||

| Multiple-symptom presentation | Chronic fatigue, pain, memory and concentration problems, disorientation, insomnia, gastrointestinal issues, sinus issues, fever, headaches and respiratory issues [41] | Qual | |

| Fatigue, bronchial complaints, hay fever, headaches, hyperactivity, hypersensitivity or allergy, mood change, sensitivity to foods, water and textiles, sinus complaints, loss of sense of smell, pollen and dust mite allergy, skin complaints (eczema, itching, inflammation) [65,90] | Qual |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coulburn, L.; Miller, W. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Impacts Related to Mould-Affected Housing: An Australian Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031854

Coulburn L, Miller W. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Impacts Related to Mould-Affected Housing: An Australian Integrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031854

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoulburn, Lisa, and Wendy Miller. 2022. "Prevalence, Risk Factors and Impacts Related to Mould-Affected Housing: An Australian Integrative Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031854

APA StyleCoulburn, L., & Miller, W. (2022). Prevalence, Risk Factors and Impacts Related to Mould-Affected Housing: An Australian Integrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031854