Citizens’ Perceptions of Landscape Changes and Their Driving Forces: Evidence from Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- I.

- Is the level of change in the landscape across municipalities at a similar level? What factors have influenced this?

- II.

- How are changes in the landscape perceived? Do perceptions of the same types of landscape changes differ in those two municipalities?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Area

2.2. Identification of Landscape Changes

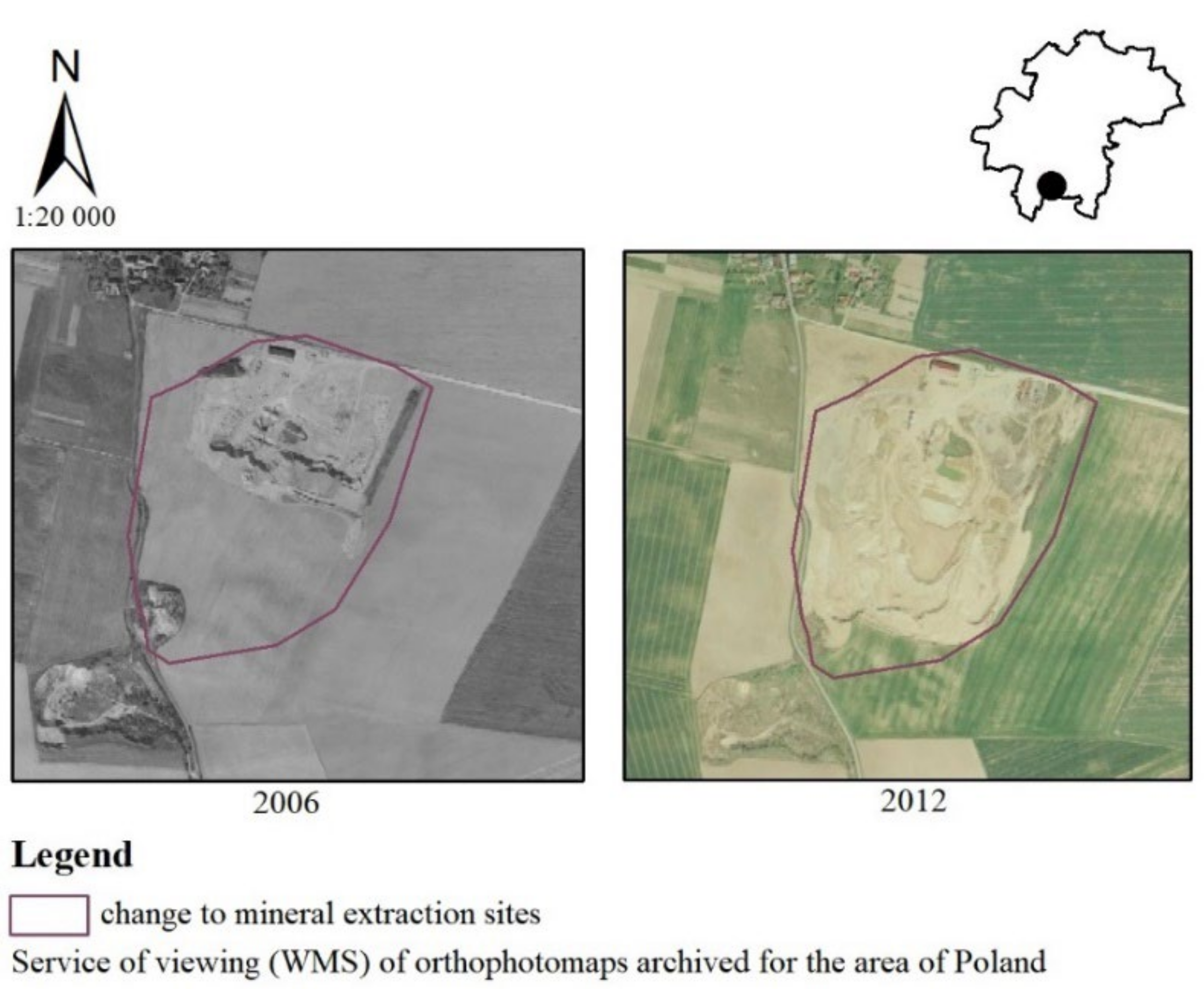

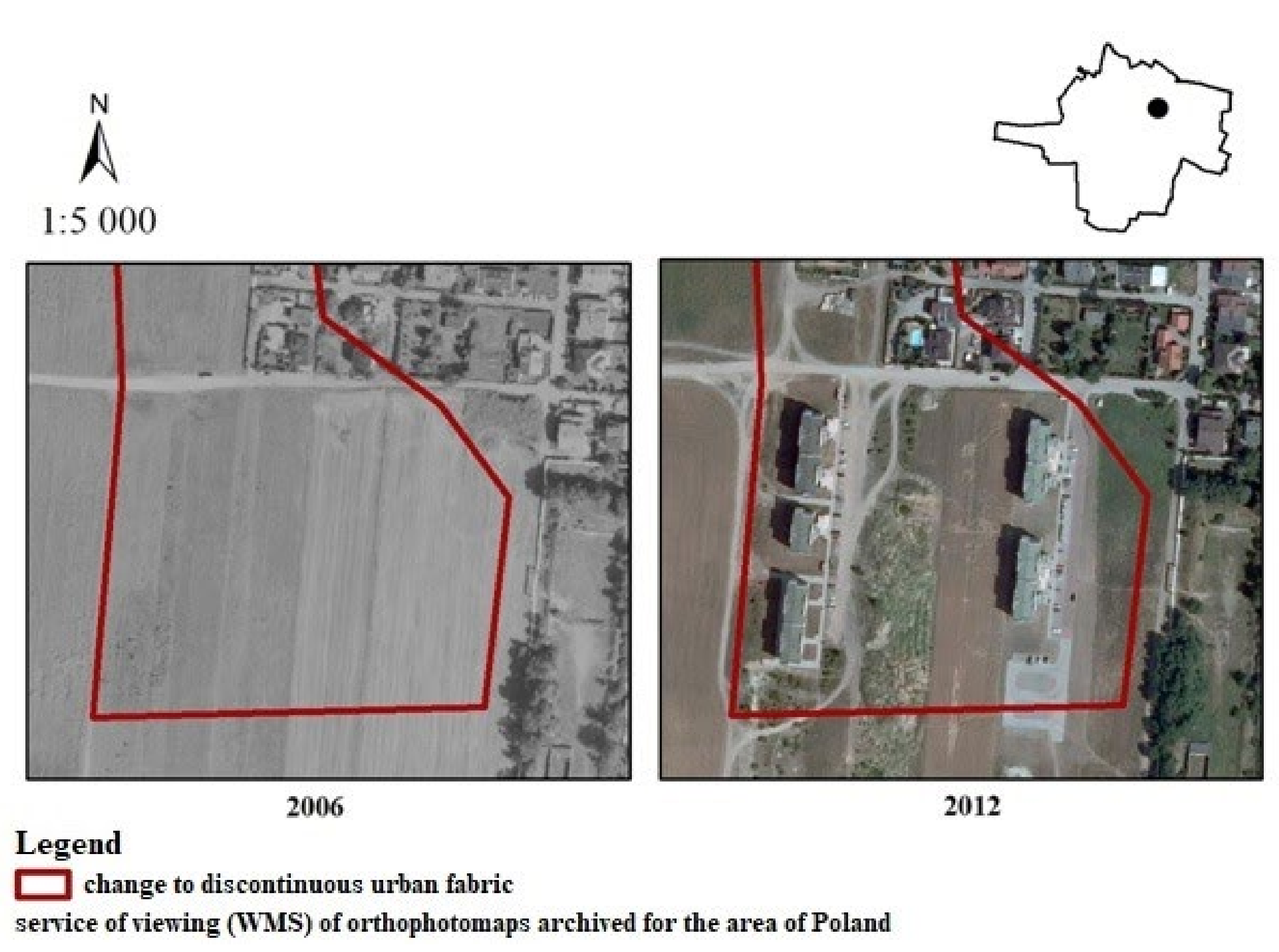

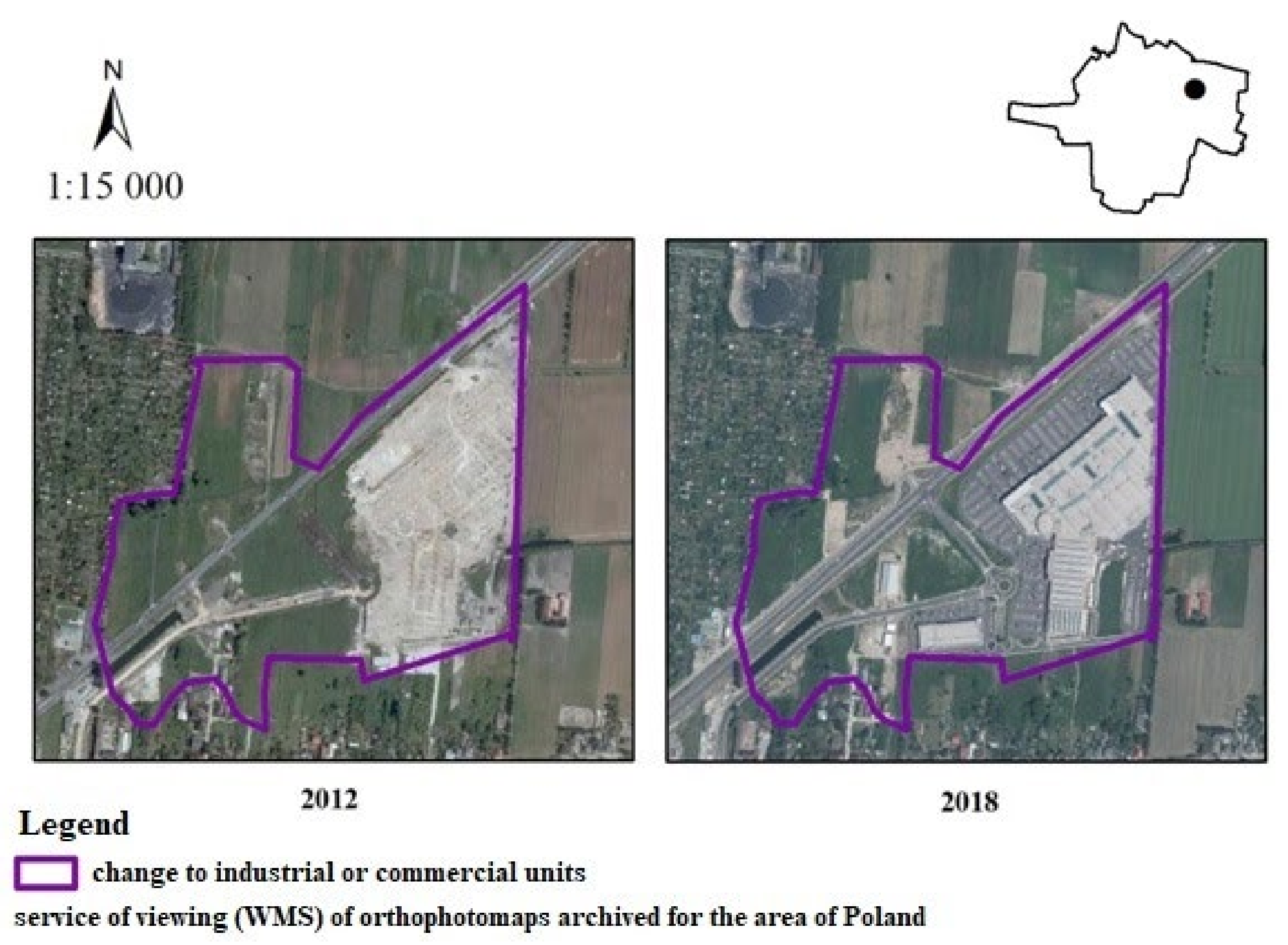

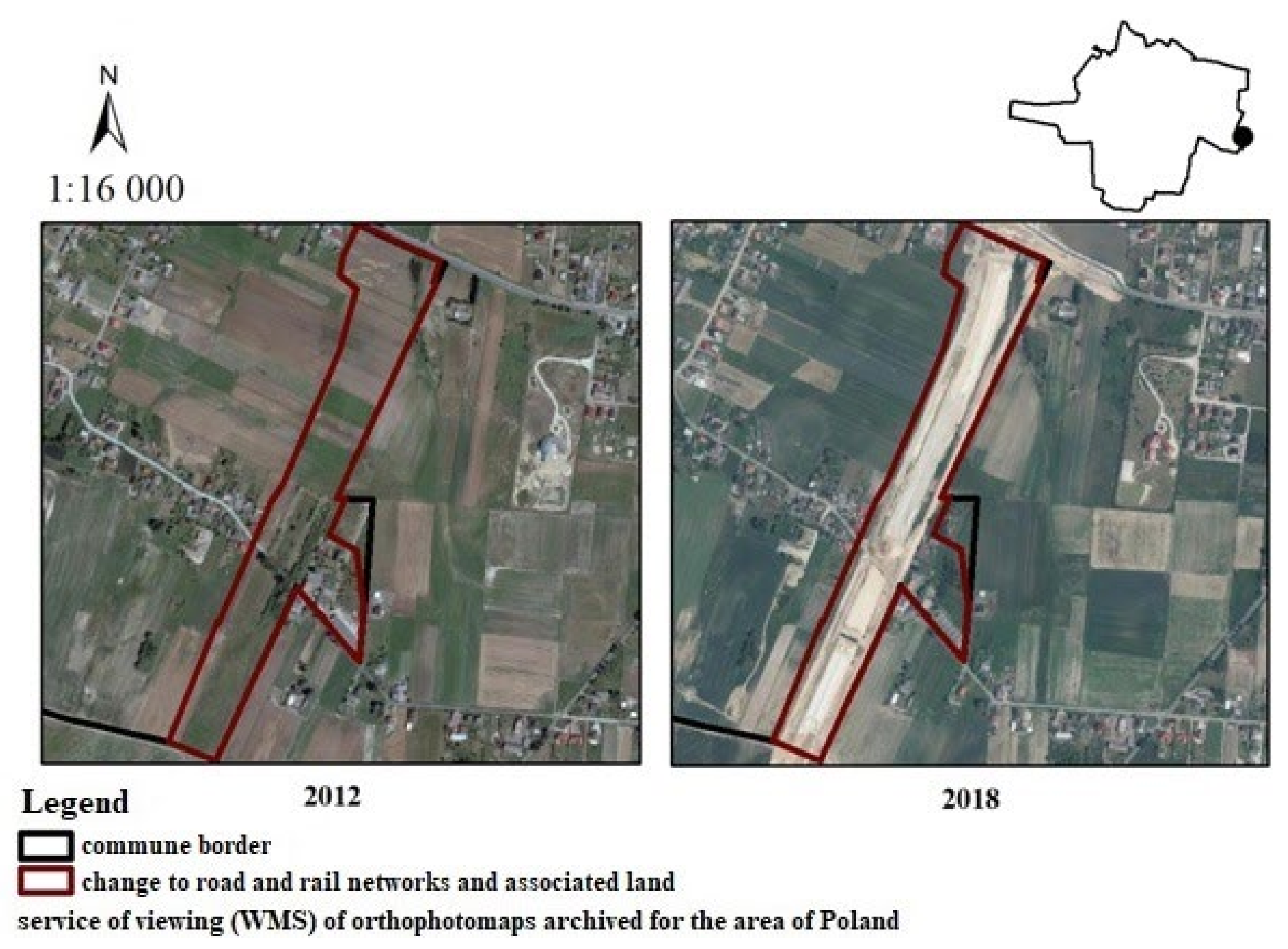

2.2.1. Research Procedure and Data

2.2.2. First Stage: Identification of the Main Landscape Changes

- (1)

- conversion of arable land for urban development;

- (2)

- conversions of arable land for commerce and services;

- (3)

- conversion of meadow and pasture for urban development;

- (4)

- conversion of arable land for communication areas;

- (5)

- conversion of arable land for airport areas, and

- (6)

- conversion of arable land for mineral extraction sites.

2.2.3. Second Stage: Identification of the Character of Landscape Changes

2.2.4. Third Stage: Identification of Driving Forces

Online Survey

Direct Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Identification of the Main Landscape Changes

3.2. Identification of the Character of Landscape Changes

3.3. Identification of Driving Forces

3.3.1. The Impact of the Changes on Landscape Perception

3.3.2. Proximate and Underlying Driving Forces

3.3.3. Interview Analysis

Ostrów Wielkopolski

- Urban development

“The biggest change is the emergence of residential development; practically at every step, a new house or block of flats is being built.”(Interviewee 4, aged 54)

“The biggest changes were the expansion of multi-family and single-family housing developments on the outskirts of the city. I think this was caused by changes in land use, or favorable purchase prices and costs to convert agricultural land for development.”(Interviewee 5, aged 23)

“On the estate where I live, many new single-family houses are being built. But for me, it is a positive change.”(Interviewee 2, aged 60)

“A new block of flats was built next to my block, in a place where nobody expected it. It fits in nicely, but there could be some place with greenery there because there is not enough of it in the city.”(Interviewee 1, aged 57)

- Industrial and commercial development

“The gallery and the ring road are big investments. I think they brought a lot of conveniences and jobs to the city, as far as the gallery is concerned.”(Interviewee 2, aged 60)

“A positive change, for sure, was the construction of the gallery. Thanks to it, a new road was built which connected my place of residence with the exit to, for example, the main street in the city and the road to Kalisz.”(Interviewee 3, aged 61)

“The only disadvantage is that the construction of the mall eliminates many of the stores in the city center, so you have to drive to the mall.”(Interviewee 1, aged 57)

- Development of road infrastructure

“For me, an important change was the construction of the ring road. I think it was needed here because it reduced traffic jams in the city and accidents. I live by the main road in the city. Thanks to the ring road, the noise was reduced. Previously, it was unbearable with open windows.”(Interviewee 1, aged 57)

“For me, the ring road is particularly burdensome as I can hear quite a lot of noise.”(Interviewee 3, aged 61)

“I miss new bicycle paths and places with greenery in the city as well as sports recreation places.”(Interviewee 4, aged 54)

Kąty Wrocławskie

- Settlement growth

“Smolec is an example of I don’t know what, it’s just a tragedy, for me. It’s a tragedy. How it’s built there, I don’t know if anyone has oversight over it at all.”(Interviewee 1, aged 75)

“They made such a kolkhoz. Around Smolec and there, in the direction of Kąty Wrocławskie, Wrocław is simply moving with the housing industry.”(Interviewee 4, aged 75)

“The fact that buildings are being erected in the so-called utility fields is a good thing. (…) No development has a negative effect; on the contrary, its absence would have a negative effect.”(Interviewee 2, aged 23)

“Do I know, what drew people here to these Kąty Wrocławskie is a wonder. It just makes me wonder. If I didn’t have to live here, I wouldn’t live in Kąty Wrocławskie. That’s why I always say to my husband, what do these people see in these parts, nothing is happening here. The swimming pool is closed all the time, constantly, there is no alternative for the youth. I myself would like to know what attracts them here. Maybe the prices, maybe it’s cheaper. I have the impression that this is the only thing that can attract people here. The proximity of the big city of Wrocław, people commute somewhere there.”(Interviewee 3, aged 47)

“People run away from Wrocław to have peace and quiet. Although, I don’t know if it’s peaceful in Smolec, where one person sits on top of another.”(Interviewee 4, aged 54)

- Development of road infrastructure

“If there was no bypass, we wouldn’t be talking about it because Wrocław would be blocked for good.”(Interviewee 4, aged 54)

“The A4 freeway is supposed to be the axis of development, but there is a problem with it because something is happening all the time, it is too narrow, too small, transit transport jams. A lot has been put on the railroad and it has been successful. This is really a proven element of railroads.”(Interviewee 4, aged 54)

“We, the residents of Smolec, would very much like there to be a ring road passing by Kąty and Kostomłoty. This is transit. If anything happens on the highway, we all feel it and it’s simply a tragedy.”(Interviewee 1, aged 75)

“A bypass of Kąty Wrocławskie would be absolutely necessary. Something like this would be useful, which would cause when A4 is blocked because there are accidents, Kąty Wrocławskie is a town in which cars drive all the time. They drive through the main street, there is also a school there. It is a nuisance for the residents.”(Interviewee 2, aged 23)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Types of driving force of landscape change |

| Political driving forces of landscape change |

| Spatial policy of the local authorities (local land-use plans) |

| Decisions of the local authorities (development conditions) |

| Local nature conservation agreements |

| Policy of the local authorities in the field of mining deposits |

| Policy of the local authorities in the field of alternative energy sources |

| Policy of the local authorities in the field of development of the local road network |

| Socio-economic driving forces of landscape change |

| Lower price levels in the local real estate market |

| Local taxes |

| The level of wealth of the municipality |

| Low unemployment in the commune |

| Proximity to place of work |

| Cultural driving forces of landscape change |

| Human population change |

| Demand for recreation and tourism equipment |

| Change in preferred place of residence (city or village) |

| The need to build second homes in recreation areas |

| Technological driving forces of landscape change |

| Local experimental investment |

| Natural/spatial driving forces of landscape change |

| Local climate change |

| Local extreme phenomena such as landslides, storms, etc. |

| Local topography |

| Soil conditions |

| Visual values |

| Values of existing spatial pattern |

| Closeness to the forest |

| Closeness to the protected area |

References

- Brandt, J.; Primdahl, J.; Reenberg, A. Rural land-use and dynamic forces—Analysis of ‘driving forces’ in space and time. In Land-Use Changes and Their Environmental Impact in Rural Areas in Europe; Krönert, R., Baudry, J., Bowler, I.R., Reenberg, A., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1999; pp. 81–102. ISBN 1 85070 047 8. [Google Scholar]

- Seabrook, L.; McAlpine, C.; Fensham, R. Cattle, crops and clearing: Regional drivers of landscape change in the Bridglow Belt, Queensland, Australia, 1840–2004. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marucci, D. Landscape history as a planning tool. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 49, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgi, M.; Hersperger, A.M.; Scheenberger, N. Driving forces of landscape change—Current and new directions. Landsc. Ecol. 2004, 19, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheenberger, N.; Bürgi, M.; Hersperger, A.M.; Ewald, K.C. Driving forces and rates of landscape change as a promising combination for landscape change research—An application on the northern fringe of the Swiss Alps. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupková, L.; Bičík, I.; Jeleček, L. At the Crossroads of European Landscape Changes: Major Processes of Landscape Change in Czechia since the Middle of the 19th Century and Their Driving Forces. Land 2021, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Landscape change and the urbanization process in Europe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 67, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyła, K.; Kulczyk-Dynowska, A. Transformations of Tourist Functions in Urban Areas of the Karkonosze Mountains, IOP. Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 072001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skokanová, H.; Falťan, V.; Havlíček, M. Driving forces of main landscape change processes from past 200 years in Central Europe—differences between old democratic and post-socialist countries. Ekológia 2016, 35, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cegielska, K.; Noszczyk, T.; Kukulska, A.; Szylar, M.; Hernik, J.; Dixon-Gough, R.; Jombach, S.; Valánszki, I.; Kovács, K.F. Land use and land cover changes in post-socialist countries: Some observations from Hungary and Poland. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, K. Zmiany przestrzenne na obszarach wiejskich w Polsce w okresie transformacji i po wejściu do Unii Europejskiej. In Obszary Wiejskie—Wiejska Przestrzeń i Ludność, Aktywność Społeczna i Przedsiębiorczość; Heffner, K., Klemens, B., Eds.; Studia KPZK PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2016; Volume 167, pp. 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliszewski, A. Problems implementing the “National Program for Expanding of Forest Cover” following Poland’s accession to the European Union. For. Res. Pap. 2012, 73, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, P.; Solecka, I.; Mrozik, K. Forest Landscape Change and Preliminary Study on Its Driving Forces in Ślęża Landscape Park (Southwestern Poland) in 1883–2013. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bürgi, M.; Bieling, C.; von Hackwitz, K.; Kizos, T.; Liesovsky, J.; Martin, M.G.; McCarthy, S.; Müller, M.; Plieninger, T.; Printsmann, A. Processes and driving forces in changing cultural landscapes across Europe. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 32, 2097–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krajewski, P. Monitoring of Landscape Transformations within Landscape Parks in Poland in the 21st Century. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antrop, M. Background concepts for integrated landscape analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 77, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llauss, A.; Nogué, J. Indicators of landscape fragmentation: The case for combining ecological indices and the perceptive approach. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 15, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M.; Broberg, A.; Tzoulas, T.; Snabb, K. Towards contextually sensitive urban densification: Location-based softGIS knowledge revealing perceived residential environmental quality. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 113, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R.; Mellander, C.; Stolarick, K. Beautiful places: The role of perceived aesthetic beauty in community satisfaction. Reg. Stud. 2011, 45, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. The nature of the view from home psychological benefits. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerebel, A.; Gélinas, N.; Déry, S.; Voigt, B.; Munson, A. Landscape aesthetic modelling using Bayesian networks: Conceptual framework and participatory indicator weighting. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 185, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J. Stability of landscape perceptions in the face of landscape change. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1997, 37, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.F. Using spatial metrics to predict scenic perception in a changing landscape: Dennis, Massachusetts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevk, T.; Golobič, M. Contentious eye-catchers: Perceptions of landscapes changed by solar power plants in Slovenia. Renew. Energy 2020, 152, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rędzińska, K.; Szulczewska, B. Landscape in change as perceived by its residents: A case study of Wilanow West in Warsaw. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.N.; Rahman, M.M.; Jashimuddin, M.; Hossain, M.M.; Islam, K.; Al Faroque, M. Analyzing multi-temporal satellite imagery and stakeholders’ perceptions to have an insight into how forest co-management is changing the protected area landscapes in Bangladesh. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 101, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Puente, M.; Campos, M.; McCall, M.K.; Muñoz-Rojas, J. Places beyond maps; integrating spatial map analysis and perception studies to unravel landscape change in a Mediterranean mountain area (NE Spain). Appl. Geogr. 2014, 52, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J. Perceptions of landscape change in a rural British Columbia community. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 85, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aretano, R.; Petrosillo, I.; Zaccarelli, N.; Semeraro, T.; Zurlini, G. People perception of landscape change effects on ecosystem services in small Mediterranean islands: A combination of subjective and objective assessments. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 112, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twongyirwe, R.; Bithell, M.; Richards, K.S.; Rees, W.G. Do livelihood typologies influence local perceptions of forest cover change? Evidence from a tropical forested and non-forested rural landscape in western Uganda. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 50, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kleemann, J.; Baysal, G.; Bulley, H.N.; Fürst, C. Assessing driving forces of land use and land cover change by a mixed-method approach in north-eastern Ghana, West Africa. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 196, 411–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.J.; van Vliet, J.; Verburg, P.H. The peri-urbanization of Europe: A systematic review of a multifaceted process. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 196, 103733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, P.; Solecka, I.; Mastalska-Cetrera, B. Landscape change index as a tool for spatial analysis. J. IOP Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 072014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, N.; Wallner, A.; Hunziker, M. The change of European landscapes: Human-nature relationships, public attitudes towards rewilding, and the implications for landscape management in Switzerland. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2910–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.; Weber, D. Public Participation GIS: A new method for national park planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 102, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H. Stories remote sensing images can tell: Integrating remote sensing analysis with ethnographic research in the study of cultural landscapes. Hum. Ecol. 2003, 31, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H.; Sell, J.L.; Taylor, J.G. Landscape perception: Research, application and theory. Landsc. Plan. 1982, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Reed, P.; Raymond, C.M. Mapping place values: 10 lessons from two decades of public participation GIS empirical research. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 116, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Municipality | Region | Area (ha) | Population | Density per 1 km2 | Type of Commune | Main Landscape Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kąty Wrocławskie | Lower Silesia | 17,700 | 25,282 | 143 | urban–rural | Flat area bordering Wrocław with a predominantly agricultural landscape. Built-up areas prevail in the central part of the commune in the city and in the north-eastern part of the commune. |

| Ostrów Wielkopolski | Greater Poland | 4190 | 71,947 | 1717 | urban | Flat area with a historical city center, recreational areas and new housing estates in the northern part, and a shopping mall and transport hub in the north-eastern part. |

| Data Used for Analysis | Type of Data | Year | Database | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corine Land Cover | Shapefile | 2006, 2012, 2018 | CLC2006, CLC2012, CLC2018 | Copernicus Land Monitoring |

| Standard archive orthophoto map | Raster with georeference | 2006, 2012, 2018 | Polish geoportal, Infrastructure for Spatial Information | Central Office of Cartography and Geodesy |

| Corine Land Cover Classes | Kąty Wrocławskie | Ostrów Wielkopolski | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deviation in Period 2006–2012 (%) | Deviation in Period 2012–2018 (%) | Deviation in Period 2006–2012 (%) | Deviation in Period 2012–2018 (%) | |

| Discontinuous urban fabric | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Industrial or commercial units | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Road and rail networks and associated land | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Airport area | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mineral extraction sites | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Construction sites | 0.3 | −0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-irrigated arable land | −2 | −2 | −2 | −1 |

| Fruit trees and berry plantations | 0 | −0.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Pastures | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mixed forest | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Transitional woodland shrub | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Landscape Change Index | 6 | 4.9 | 5 | 2 |

| CLC Code | CLC Class | Kąty Wrocławskie | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2012 | 2018 | |||||

| Area (ha) | Area (%) | Area (ha) | Area (%) | Area (ha) | Area (%) | ||

| 1.1.2. | Discontinuous urban fabric | 1181.17 | 6.69 | 1395.49 | 7.90 | 1695.40 | 9.60 |

| 1.2.1. | Industrial or commercial units | 88.70 | 0.5 | 98.16 | 0.55 | 210.81 | 1.19 |

| 1.2.2. | Road and rail networks and associated land | - | - | 117.03 | 0.66 | 117.03 | 0.66 |

| 1.2.4. | Airport area | 38.23 | 0.22 | 47.44 | 0.27 | 47.44 | 0.27 |

| 1.3.1. | Mineral extraction sites | - | 53.12 | 0.30 | 53.12 | 0.30 | |

| 1.3.3. | Construction sites | 57.32 | 0.32 | - | |||

| 2.1.1. | Non-irrigated arable land | 12,882.13 | 72.92 | 12,557.25 | 71.09 | 12,177.13 | 68.93 |

| 2.2.2. | Fruit trees and berry plantations | 188.19 | 1.06 | 89.79 | 0.51 | 64.42 | 0.36 |

| 2.3.1. | Pastures | 125.13 | 0.71 | 125.13 | 0.71 | 125.13 | 0.71 |

| 2.4.2. | Complex cultivation patterns | 299.47 | 1.7 | 298.97 | 1.69 | 339.56 | 1.92 |

| 2.4.3. | Land principally occupied by agriculture with significant areas of natural vegetation | 513.77 | 2.91 | 452.62 | 2.56 | 460.16 | 2.60 |

| 3.1.3. | Broad-leaved forest | 105.17 | 0.6 | 110.67 | 0.63 | 110.67 | 0.63 |

| 3.1.3. | Mixed forest | 2219.04 | 12.56 | 2182.00 | 12.35 | 2184.13 | 12.36 |

| 3.2.4. | Transitional woodland shrub | 24.32 | 0.14 | 80.28 | 0.45 | 80.28 | 0.45 |

| CLC Code | CLC Class | Ostrów Wielkopolski | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2012 | 2018 | |||||

| Area (ha) | Area (%) | Area (ha) | Area (%) | Area (ha) | Area (%) | ||

| 1.1.1. | Continuous urban fabric | 57.76 | 1.38 | 57.76 | 1.38 | 57.76 | 1.38 |

| 1.1.2. | Discontinuous urban fabric | 1728.00 | 41.24 | 1775.00 | 42.36 | 1818.00 | 43.39 |

| 1.2.1. | Industrial or commercial units | 411.63 | 9.82 | 440.00 | 10.50 | 470.00 | 11.22 |

| 1.2.2. | Road and rail networks and associated land | 32.25 | 0.77 | 31.00 | 0.74 | 46.00 | 1.10 |

| 1.4.1. | Green urban areas | 25.62 | 0.61 | 25.62 | 0.61 | 25.62 | 0.61 |

| 1.4.2. | Sport and leisure facilities | 141.34 | 3.37 | 141.34 | 3.37 | 141.34 | 3.37 |

| 2.1.1. | Non-irrigated arable land | 884.57 | 21.11 | 806.00 | 19.24 | 740.00 | 17.66 |

| 2.3.1. | Pastures | 396.09 | 9.45 | 400.00 | 9.55 | 379.00 | 9.05 |

| 3.1.3. | Broad-leaved forest | 361.74 | 8.63 | 361.74 | 8.63 | 361.74 | 8.63 |

| 3.1.2. | Coniferous forest | 122.99 | 2.94 | 122.99 | 2.94 | 122.99 | 2.94 |

| 5.1.2. | Water bodies | 28.30 | 0.68 | 28.30 | 0.68 | 28.30 | 0.68 |

| Variable | Ostrów Wielkopolski | Kąty Wrocławskie | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | |

| Duration of living | ||||

| 1–5 years | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 5–15 years | 2 | 5 | 9 | 21 |

| 15–30 years | 20 | 48 | 11 | 26 |

| More than 30 years | 19 | 45 | 21 | 50 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| High school | 18 | 43 | 7 | 17 |

| Higher | 23 | 55 | 26 | 62 |

| Income level | ||||

| Lack of earnings | 2 | 5 | 4 | 10 |

| Low (around minimum wage) | 6 | 14 | 5 | 13 |

| Medium (below the national average) | 22 | 52 | 9 | 23 |

| High (over the national average) | 12 | 29 | 20 | 52 |

| Age | ||||

| Below 20 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 21–30 | 20 | 48 | 3 | 7 |

| 31–40 | 9 | 21 | 11 | 26 |

| 41–50 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 21 |

| 51–60 | 9 | 21 | 2 | 5 |

| Over 60 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Assessment of the level of landscape change | ||||

| Low | 9 | 21 | 6 | 14 |

| Medium | 18 | 43 | 12 | 29 |

| High | 15 | 36 | 24 | 57 |

| Age Group | Ostrów Wielkopolski | Kąty Wrocławskie | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents (%) | Census Data (%) | Respondents (%) | Census Data (%) | |

| Below 20 | 3 | 16 | 2 | 22 |

| 21–30 | 48 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 31–40 | 21 | 14 | 40 | 16 |

| 41–50 | 5 | 13 | 33 | 16 |

| 51–60 | 21 | 11 | 7 | 10 |

| Over 60 | 2 | 37 | 7 | 26 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solecka, I.; Krajewski, P.; Krzyżanek, A.; Garczyńska, A. Citizens’ Perceptions of Landscape Changes and Their Driving Forces: Evidence from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031688

Solecka I, Krajewski P, Krzyżanek A, Garczyńska A. Citizens’ Perceptions of Landscape Changes and Their Driving Forces: Evidence from Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031688

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolecka, Iga, Piotr Krajewski, Aleksandra Krzyżanek, and Ada Garczyńska. 2022. "Citizens’ Perceptions of Landscape Changes and Their Driving Forces: Evidence from Poland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031688

APA StyleSolecka, I., Krajewski, P., Krzyżanek, A., & Garczyńska, A. (2022). Citizens’ Perceptions of Landscape Changes and Their Driving Forces: Evidence from Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031688