Factors Affecting Citizen Trust and Public Engagement Relating to the Generation and Use of Real-World Evidence in Healthcare

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Value of RWD

1.2. Challenges to the Implementation of RWE

- Methodological issues: Most health data are captured routinely to serve a narrow purpose. Despite guidelines regarding data management (e.g., the FAIR [Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable] Principles on data management) [9], there is no overall consensus on data collection for RWE studies. In addition, there is limited guidance outside of clinical trials or studies to specify the type of data that should be captured, i.e., minimal datasets in a routine clinical setting and the definition of clinically meaningful data. This lack of data standardization, completeness, quality assurance, and accessibility amounts to a serious limitation on comparison and pooling of data for different datasets and the usefulness of collected data for answering specific scientific and medical questions [4,10].

- Lack of harmonization between RWD collection systems: Deriving useful insights from the sharing of data between different centers or countries is possible only through data collection harmonization, data transparency, and endorsement of collection methods within individual countries and a common interest in answering a specific question with the collected data.

- Data-access and data-sharing limitations: Data sharing between countries is subject to further practical challenges, often because the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) impedes easy understanding of how to exchange data for research. Despite the harmonizing intentions of GDPR, significant variations remain at national levels in interpretations of this legislation.

- Limitations of regulatory agencies and HTAs/payers: Attitudes toward use of RWD vary across Europe, with differing degrees of acceptance for its different policy areas and differing expertise to critically assess its use in agencies’ decisions and recommendations [11]. Guidance provided by agencies often reflects the ideal end-stage for RWD, where data are available in sufficient quantities and are of sufficient quality. Efforts are needed to guide stakeholders in this learning healthcare ecosystem state to use what is available appropriately.

- Lack of citizen trust in data sharing: RWD can be obtained from either regional or national databases, where researchers can be granted access to the data, or from sponsored RWD studies, which require informed consent for data collection from participating patients. The former databases are obligated to ensure both data security and patient confidentiality. Widespread suspicion within the general population, a reluctance to surrender data to governments or multinational corporations, and concerns over cybersecurity hinder the sharing of patient data that could advance medical research. To circumvent these issues, patient involvement in the collection of RWD is crucial. The French COVID-19 Corona Tracker had a successful uptake, while German citizens were broadly resistant to their own country’s version. It is notable that the French model for data access provided patients with tangible outcomes from sharing their information, in a similar manner to the EU Patient Cancer Digital Centre/Platform, while the German system focused on tracking only and did not offer citizens much in terms of benefits or services.

1.3. Coherence in EU Health Policy Making

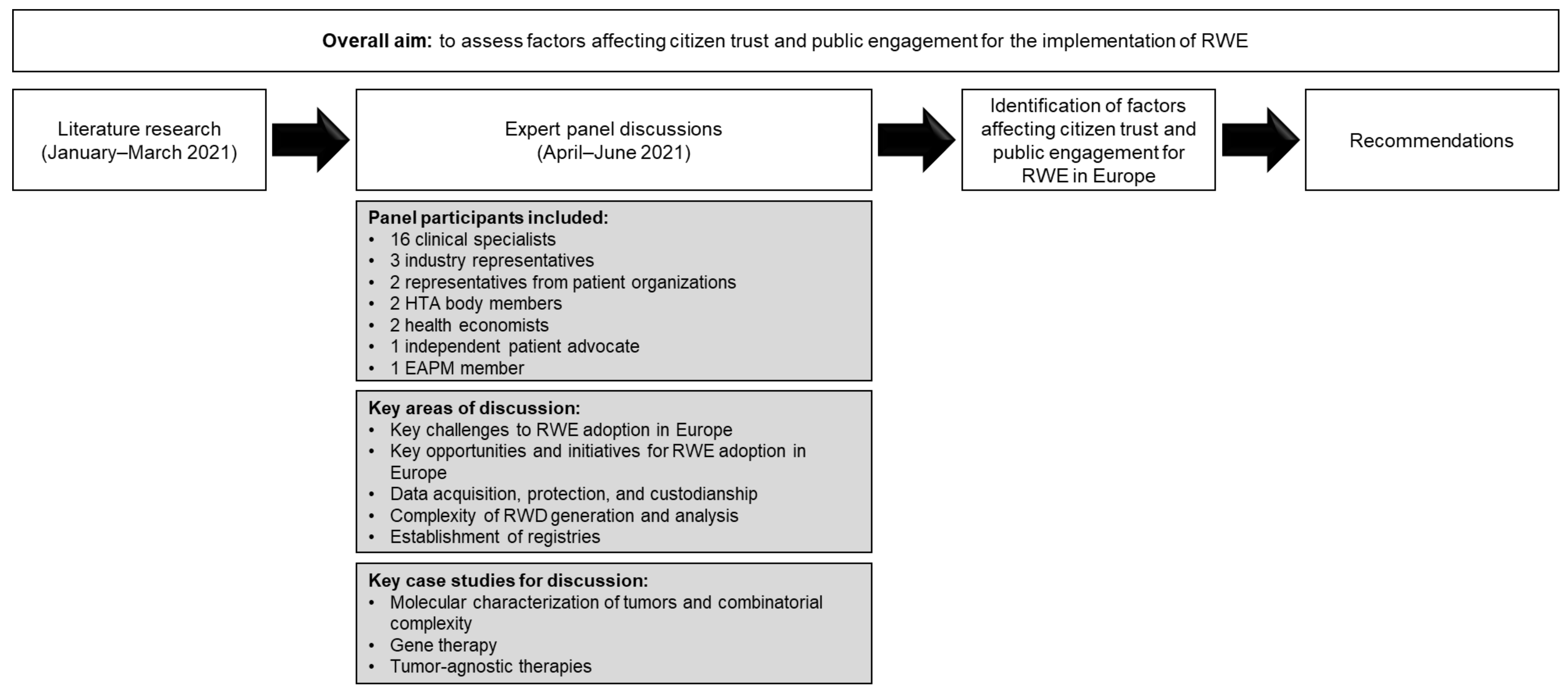

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Public Trust and Access to Data

3.2. Evidence Framework

3.3. Cross-Border Governance Framework to Facilitate RWE Decision-Making

3.4. Citizens—Improvements in Healthcare Decisions

4. Discussion

4.1. Health Policy within the EU

4.2. Recent and Upcoming Changes and Valuable Initiatives to Support RWE across Europe

4.2.1. Public Trust and Access to Data

| Initiative | Country | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | ||

| European Cancer Patient Digital Centre | Europe | Facilitates the uptake of digital technologies to maximize their potential in cancer care [28] |

| RWE4Decisions | Europe | Brings together multiple stakeholders (policy makers, HTAs, payers, regulatory agencies, patient groups, academics, and industry) to decide which types of RWD could be collected for informing decisions by healthcare systems, clinicians, and patients [29] |

| Pan-Cancer Global Registry (industry led) | Global | Collection of health data from patients across the world with different cancers |

| Enables Access to Data | ||

| Findata | Finland | Provides permits for access to patient-level data from different controllers and delivers these data to the user [26] |

| Health Data Hub | France | Covers the French National Health Data System (SNDS), which includes all the health data associated with a H-health insurance reimbursement from hospital treatments, doctors’ visits, participation in a research cohort, or an epidemiological/practice register [30] |

| Electronic Cross-Border Health Services | Select European countries but to be implemented across 25 EU countries by 2025 [27] | Allows sharing of patient summaries to doctors from other EU countries and permits pharmacists to dispense e-prescriptions to patients from other EU countries [27] |

| European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases (EJP RD) | 26 EU Member States, UK, Canada, and seven associated countries (Armenia, Georgia, Israel, Norway, Serbia, Switzerland, and Turkey) [31] | Supports research into rare diseases by offering funding, pooling data resources and tools, educating researchers, and accelerating translation of results into effective treatments [31] |

| European Health Data Space (EHDS) | EU | One of the priorities of the European Commission 2019–2025 is to promote better access to data from different sources (electronic health records, genomics data, patient registry data, etc.) to support healthcare delivery and for use in research and health policy making. The system will address three main issues: strong data governance, data quality and interoperability, and strong infrastructure [32] |

| Data Use/Evidence Generation | ||

| FinnGen | Finland | A study that combines genome information from Finnish biobanks with national healthcare registry data [33] |

| Drug Rediscovery Protocol (DRUP) study | The Netherlands | Assesses the efficacy and safety of commercially available, targeted anti-cancer drugs in patients with rare subgroups of cancers with actionable mutations [34] |

| Coverage with evidence development, e.g., the Cancer Drugs Fund | UK | Use of real-world data from interventions and relevant comparators from several sources to assess re-evaluation and funding of anti-cancer therapies [35] |

| GetReal Institute | Europe | Facilitates collaboration between RWE stakeholders to help to overcome challenges related to its generation and use, as well as providing a platform to assess and improve RWE quality and provide education on best practices [36] |

| European Initiative to Understand Cancer (UNCAN) | EU | Use of Europe-wide data to improve understanding of cancer risk, screening, diagnosis, treatment, quality of life, etc. [37] |

| Data Collection/Data Use/Evidence Generation | ||

| National Health Service (NHS) Digital | UK | Organization responsible for managing and keeping national health data safe, as well as using it to improve understanding of health problems and to improve NHS services [38] |

| Data Analysis and Real World Interrogation Network (DARWIN) EU | EU | An EMA initiative, which aims to establish a catalog of high-quality, validated observational data that can be used in non-interventional studies to generate RWE to support regulatory decision-making [39] |

| Policy Making | ||

| German Genomics Initiative (genomDE) | Germany | Promotes the introduction of genomic sequencing into routine healthcare for combination with other relevant health data to guide treatment decisions [40] |

| Genomic Medicine Sweden (GMS) | Sweden | Promotes collaboration between different stakeholders to allow effective utilization of advanced technologies for high-quality genomic testing in routine clinical practice [41] |

| Engagement/Education | ||

| Innovative Partnership for Action Against Cancer (iPAAC) and Horizon 2020 Joint Action | 24 European countries | Work Package 6—Genomics in Cancer Control and Care: Aims to engage and educate citizens/healthcare professionals/policy makers regarding issues on the use of genomic information in healthcare [42] |

4.2.2. Evidence Framework

4.2.3. Cross-Border Governance Framework to Facilitate RWE Decision-Making

4.2.4. Citizens—Improvements in Healthcare Decisions

4.3. Key Recommendations to Support the Use of RWE-Based Studies across Europe

- To develop consensus guidelines to standardize RWD generation and use. This should include best practice to shape methodology, analysis, and reporting of RWD and RWE, data sharing according to GDPR, and assessment of the clinical utility of RWD generation. Health data must be secure, provide a high level of quality, and ensure interoperability.

- The development of guidelines to allow consistent reporting of RWE-based studies in medical journals; few medical journals provide specific instructions for authors wishing to submit manuscripts on this type of study, leading to a lack of alignment in methods for conducting and reporting such data [45]. RWE-based studies that follow these guidelines should address payer and regulatory body concerns regarding the generation of RWE, thus aiding their incorporation into the value assessment pathway.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hechenbleikner, E.M.; Samarov, D.V.; Lin, E. Data explosion during COVID-19: A call for collaboration with the tech industry & data scrutiny. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 23, 100377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cave, A.; Kurz, X.; Arlett, P. Real-world data for regulatory decision making: Challenges and possible solutions for Europe. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 106, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Booth, C.M.; Karim, S.; Mackillop, W.J. Real-world data: Towards achieving the achievable in cancer care. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deverka, P.A.; Douglas, M.P.; Phillips, K.A. Use of real-world evidence in us payer coverage decision-making for next-generation sequencing-based tests: Challenges, opportunities, and potential solutions. Value Health 2020, 23, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, B.A.; Gajra, A.; Zettler, M.E.; Phillips, T.D.; Phillips, E.G., Jr.; Kish, J.K. Use of real-world evidence to support FDA approval of oncology drugs. Value Health 2020, 23, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- From Testing to Targeted Treatment Program (FT3). 3 Representative Working Groups to Co-Create and Deliver. Available online: https://www.fromtestingtotargetedtreatments.org/working-groups/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Kim, H.-S.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.H. Real-world evidence versus randomized controlled trial: Clinical research based on electronic medical records. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2018, 33, e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, P.; Bouharati, C.; Rambiritch, V.; Jose, N.; Karamchand, S.; Chilton, R.; Leisegang, R. Real-world evidence and product development: Opportunities, challenges and risk mitigation. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2021, 133, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dickson, D.; Johnson, J.; Bergan, R.; Owens, R.; Subbiah, V.; Kurzrock, R. The master observational trial: A new class of master protocol to advance precision medicine. Cell 2020, 180, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Makady, A.; Ten Ham, R.; de Boer, A.; Hillege, H.; Klungel, O.; Goettsch, W. GetReal Workpackage 1. Policies for use of real-world data in health technology assessment (HTA): A comparative study of six HTA agencies. Value Health 2017, 20, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Health Technology Assessment and Amending Directive 2011/24/EU. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018PC0051&from=EN (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Commission. European Health Union: Protecting the Health of Europeans and Collectively Responding to Cross-border Health Crises. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/promoting-our-european-way-life/european-health-union_en (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Franklin, P.K. Public health within the EU policy space: A qualitative study of Organized Civil Society (OCS) and the Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach. Public Health 2016, 136, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrouk, A.; Lacombe, D.; Meunier, F. Diverging EU health regulations: The urgent need for co ordination and convergence. J. Cancer Policy 2018, 17, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUR-Lex. Summaries of EU Legislation: Public Health. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/summary/chapter/29.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Union. Supporting Public Health in Europe. Available online: https://europa.eu/european-union/topics/health_en (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- McKinsey & Company. Personalized Medicines: The Path Forward. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotcom/client_service/pharma%20and%20medical%20products/pmp%20new/pdfs/mckinsey%20on%20personalized%20medicine%20march%202013.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Horgan, D.; Kent, A. EU health policy, coherence, stakeholder diversity and their impact on the EMA. Biomed. Hub. 2017, 2 (Suppl. 1), 481301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/non_communicable_diseases/docs/eu_cancer-plan_en.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Commission. Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/medicinal-products/pharmaceutical-strategy-europe_en (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Commission. Mission Area: Cancer. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe/missions-horizon-europe/cancer_en (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Commission. EU Health Policy: Overview. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/policies/overview_en (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO). Sixteen EU Member States Sign the Genomics Declaration [News Release]. Available online: https://www.esmo.org/oncology-news/archive/sixteen-eu-member-states-sign-the-genomics-declaration (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Empty on Enabling the Digital Transformation of Health and Care in the Digital Single Market; Empowering Citizens and Building a Healthier Society. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0233&rid=8 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Findata—Health and Social Data Permit Authority. Findata Website. Available online: https://findata.fi/en/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Commission. Electronic Cross-Border Health Services. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/ehealth/electronic_crossborder_healthservices_en (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Cancer Organisation. Digital Health Network. Available online: https://www.europeancancer.org/topic-networks/4:digital-health.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- RWE4Decisions. RWE4Decisions Website. Available online: https://rwe4decisions.com/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Health Data Hub. Health Data Hub FAQ. Available online: https://www.health-data-hub.fr/page/faq-english (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases (EJP RD). What Is EJP RD? Project Structure. Available online: https://www.ejprarediseases.org/what-is-ejprd/project-structure/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Commission. European Health Data Space. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/ehealth/dataspace_en (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM); University of Helsinki. FinnGen Website. Available online: https://www.finngen.fi/en (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Van der Velden, D.L.; Hoes, L.R.; van der Wijngaart, H.; van Berge Henegouwen, J.M.; van Werkhoven, E.; Roepman, P.; Schilsky, R.L.; de Leng, W.W.J.; Huitema, A.D.R.; Nuijen, B.; et al. The Drug Rediscovery protocol facilitates the expanded use of existing anticancer drugs. Nature 2019, 574, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS England. Appraisal and Funding of Cancer Drugs from July 2016 (Including the New Cancer Drugs Fund): A New Deal for Patients, Taxpayers and Industry. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/cdf-sop.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- GetReal Institute. GetReal Institute Website. Available online: https://www.getreal-institute.org/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Cancer Organisation. Interim Report of the Mission Board for Cancer. Available online: https://www.europeancancer.org/policy/13-policy/11-interim-report-of-the-mission-board-for-cancer (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- NHS Digital. Data. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Data Analysis and Real World Interrogation Network (DARWIN EU). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/how-we-work/big-data/data-analysis-real-world-interrogation-network-darwin-eu (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Federal Ministry of Health. The German Genomics Initiative—GenomDE. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/en/international/european-health-policy/genomde-en.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Genomic Medicine Sweden (GMS). Sweden’s Ambitious National Collaboration for Genomic Medicine. Available online: https://genomicmedicine.se/en/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Innovative Partnership for Action Against Cancer (iPAAC). Work Package 6—Genomics in Cancer Control and Care. Available online: https://www.ipaac.eu/en/work-packages/wp6/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS); Madiega, T. EU Guidelines on Ethics in Artificial Intelligence: Context and Implementation. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/640163/EPRS_BRI(2019)640163_EN.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM). DiGA Digital Health Applications. Available online: https://www.bfarm.de/EN/Medical-devices/Tasks/Digital-Health-Applications/_node.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Oehrlein, E.M.; Graff, J.S.; Perfetto, E.M.; Mullins, C.D.; Dubois, R.W.; Anyanwu, C.; Onukwugha, E. Peer-reviewed journal editors’ views on real-world evidence. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2018, 34, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| # | Framework | Public Trust and Access to Data | Evidence Framework | Cross-Border Governance Framework to Facilitate RWE Decision-Making | Citizens—Improvements in Healthcare Decisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Optimal | Transnational access to RWE according to applicable regulations and best practice guidance | Alignment of evidence needs to incentivize and ensure investment for innovative healthcare that can be delivered on a global scale and at a reduced cost for healthcare systems | Early dialogue with regulators, payers, and insurers, ad hoc infrastructure, guidelines, common global standards | Evidence exists to ensure rational allocation of resources for health and well-being; thus, improving healthcare system efficiencies |

| 4 | European | Governance framework for transnational protected access to quality-controlled data allows for evidence to be developed and accepted according to the applicable regulations and requirements across EU and Member States. Governance framework is aligned with regulator and payer requirements | A mechanism to communicate on the use of RWE to increase public trust with studies; showing how its use supports clinical and reimbursement decisions and promotes innovation across the EU. This would allow improved use of RWE in healthcare systems | A framework for RWE utilization agreed through an EU health governance framework that follows common standards and evidence requirements to facilitate decision-making and prioritization of evidence challenges by regulators and payers | Better prevention, diagnostic, and treatment decisions across the EU. Improvements in patient and citizen QoL. Healthcare actors, patients, and citizens call for framework utilization to support the best use of RWE |

| 3 | National | Alignment with EU regulations and prioritization of evidence challenges across Member States. Early dialogue with regulators/payers | Data from national clinical centers and research institutions are accessible for RWE decision makers | Governance framework that facilitates the federation of national infrastructure to enable collection, use, and interpretation of data for clinical and reimbursement decisions | Patients and citizens benefit from RWE being shared at the national level and there is a standard for evidence alignment |

| 2 | Regional /Local | Alignment with national regulations and inter-regional sharing of data for RWE | Data from federated regional clinical centers and research institutions are accessible for RWE decision makers | Regional infrastructure to reuse genomics and health data for RWE decision-making is lacking | Patients and citizens benefit from RWE being shared and utilized at the regional level |

| 1 | Elementary stage | Lack of alignment with regulation that prevents use of RWD or RWE. Lack of citizen trust leading to the absence of a system for RWE | Lack of methodology for an evidence framework to assess RWE. No agreed endpoints | No national infrastructure or governance available for adoption of RWE. No early dialogue between regulators and payers | No evidence is taken into consideration during patient diagnosis or treatment decision-making |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Horgan, D.; Borisch, B.; Cattaneo, I.; Caulfield, M.; Chiti, A.; Chomienne, C.; Cole, A.; Facey, K.; Hackshaw, A.; Hendolin, M.; et al. Factors Affecting Citizen Trust and Public Engagement Relating to the Generation and Use of Real-World Evidence in Healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031674

Horgan D, Borisch B, Cattaneo I, Caulfield M, Chiti A, Chomienne C, Cole A, Facey K, Hackshaw A, Hendolin M, et al. Factors Affecting Citizen Trust and Public Engagement Relating to the Generation and Use of Real-World Evidence in Healthcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031674

Chicago/Turabian StyleHorgan, Denis, Bettina Borisch, Ivana Cattaneo, Mark Caulfield, Arturo Chiti, Christine Chomienne, Amanda Cole, Karen Facey, Allan Hackshaw, Minna Hendolin, and et al. 2022. "Factors Affecting Citizen Trust and Public Engagement Relating to the Generation and Use of Real-World Evidence in Healthcare" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031674

APA StyleHorgan, D., Borisch, B., Cattaneo, I., Caulfield, M., Chiti, A., Chomienne, C., Cole, A., Facey, K., Hackshaw, A., Hendolin, M., Georges, N., Kalra, D., Tumienė, B., & von Meyenn, M. (2022). Factors Affecting Citizen Trust and Public Engagement Relating to the Generation and Use of Real-World Evidence in Healthcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031674