Clinician Perspectives of Communication with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Managing Pain: Needs and Preferences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting and Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Quantitative Data—Cultural Awareness and Communication Needs Survey

2.4.2. Qualitative Data—Focus Groups

2.5. Researchers’ Characteristics and Reflexivity

3. Results

3.1. Cultural Awareness and Communication Needs Survey

3.1.1. Demographics of Participants

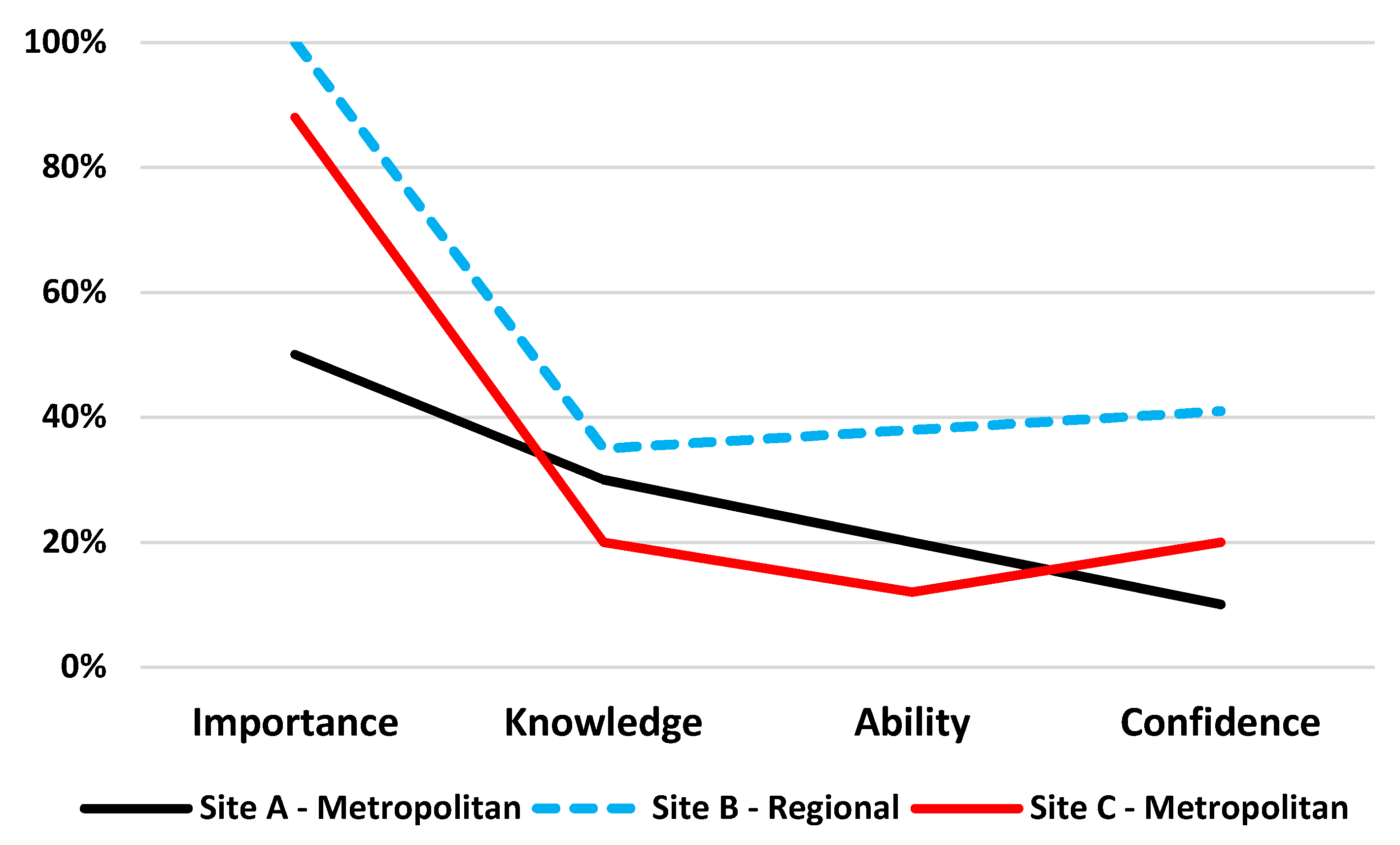

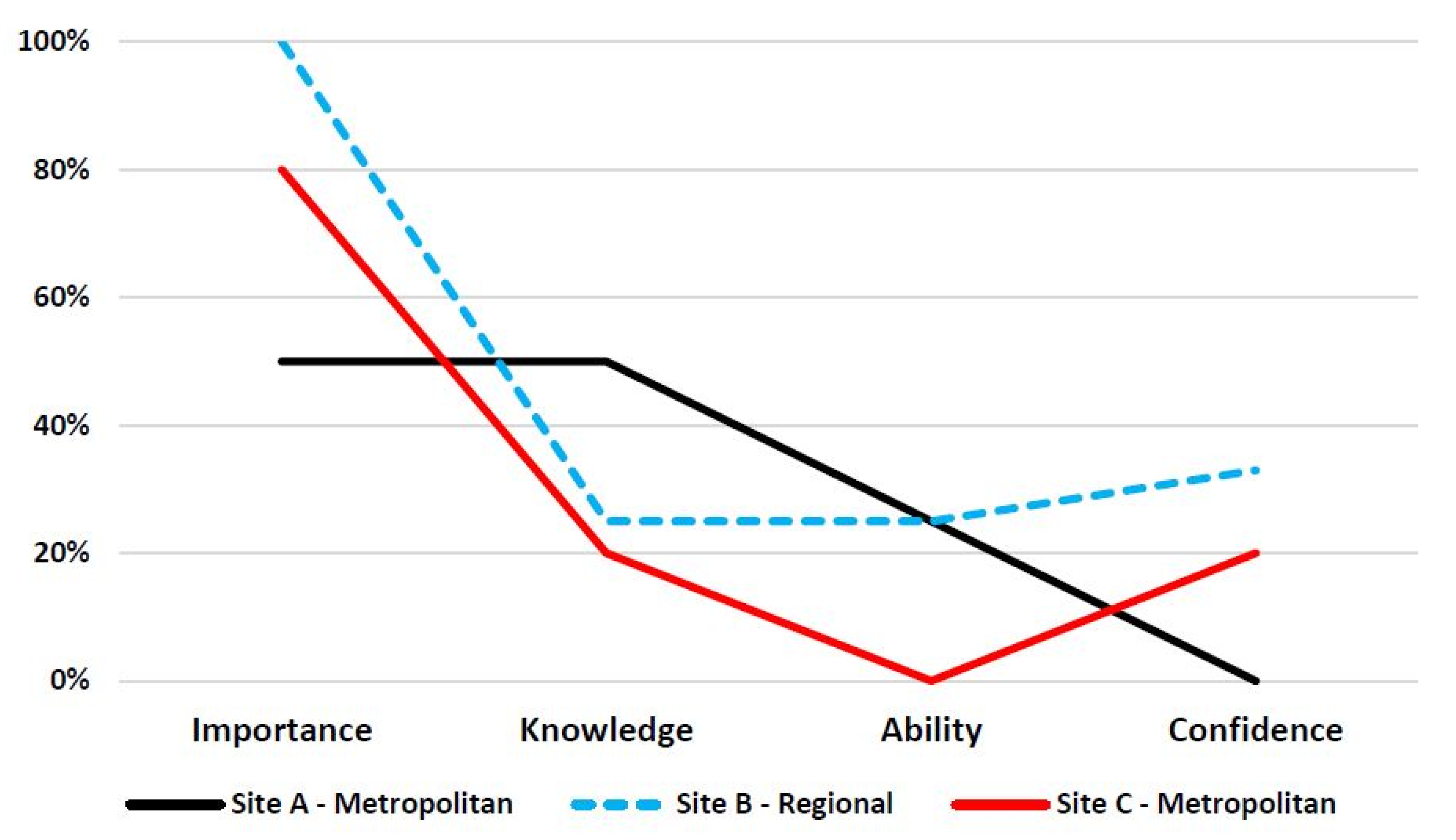

3.1.2. Communication Skills and Awareness Ratings

3.2. Focus Groups

3.2.1. Demographics of Participants

3.2.2. Findings

C8: “You can get caught up in your head worrying about being offensive or just using the wrong words or making a mistake that is the thing that causes them [Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients] to want to go somewhere else or not seek help at all”.(Clinician at a metropolitan service)

C4: “I don’t know if this is right or wrong but I wish someone had have told me that it’s okay to ask if somebody identifies [as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander] and where there family is or where they’re from and not be afraid to ask”.(Clinician at a metropolitan service)

C6: “I guess sometimes I feel like I assume what’s going to be okay to ask a female patient versus a male patient. Maybe if we were confident in that a little bit more I think that would you know I guess feel a little bit more competent and comfortable asking particular questions if we had a bit better understanding about what’s appropriate to ask I suppose”.(Clinician at the regional service)

C11: “I think a local context of history is really useful and just understanding and fleshing out your comments that you’ve made about, “It’s not our culture that makes us sick”, what that means and you know the facts of history and politics and why we are where we are. I find those things as you say confronting but really important to put out there in the middle and acknowledged”.(Clinician at the regional service)

C1: “I think forming that relationship with your health workforce; your Indigenous health workforce is really key as well. Because some of those health workers and some of those liaison officers are actually traditional owners and they hold a community authority, which is really valuable in terms of connecting with our consumers and clients”.(Clinician at a metropolitan service)

C6: “Like one thing that I like I think and this is going back ages ago was that, and I might be wrong, that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders don’t like to come to hospital because there’s that fear that if they don’t go back home, is that right? Then their spirit doesn’t rest? Or is that not right?”.(Clinician at the metropolitan service)

C9: “I feel like trying to bridge that gap between what I know clinically works for trauma and I’m labelling it as trauma because pain is so intimately connected to that. But I guess coming back to what I was saying earlier and what you were explaining about is that there’s parts that I will never be capable of working with maybe on that. And I don’t know where else to refer those people to, I don’t know. I want to be able to give a recommendation but all I know is mental health and I know that doesn’t cut it and it’s so frustrating because that is what will help their pain. I don’t know if that’s, I don’t know how to answer that”.(Clinician at a metropolitan service)

C14: “We use a lot of metaphors for educating people about pain and it could be good to kind of develop some ideas to make them a little bit more culturally appropriate and more engaging for the Indigenous population”.(Clinician at a metropolitan service)

C7: “For example this patient said, “I was bullied in school because I was a blackfella” so I was like, “Aaah so…”. I didn’t know, I didn’t know what that meant until later on when someone else said, “Why didn’t you pick up on that?” I was like, “I didn’t know””.(Clinician at a metropolitan service)

C9: “One size fits all is probably not going to address everyone’s needs. Because although we all work together we all have different training backgrounds and different experience backgrounds so I would think that a mixture of opportunities where people identify what particular skill they want to… skills or knowledge”.(Clinician at a metropolitan service)

C9: “So reflecting on perhaps some people are very confident in their communication style and clinical information gathering but are not sure you know “How do I bring in services practically?” all those sorts of things. Whereas other people might be like, “Oh well I’m really confident to ask Indigenous Liaison to come along but then how do I adapt my interpersonal skills?””.(Clinician at a metropolitan service)

C10: “You know in an online module and things like that, your click-through, I don’t think that I have got as much out of the online modules as compared to when I’ve sat in an interactive classroom set up by the gentleman sitting two seats over from me”.(Clinician at a regional service)

C9: “like it’s always nice to mix things together but obviously with learning it needs to be relevant to the role”.(Clinician at a regional service)

C5: “I think it should be a kind of mixture because you’re going to have mixed personalities, introverted and extraverted and for some people complete interactive workshop is going to be boring for example for myself if it would be completely interactive and no didactic talk”.(Clinician at a regional service)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Melzack, R. From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain 1999, 82 (Suppl. 6), S121–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittinty, M.M.; McNeil, D.W.; Jamieson, L.M. Limited evidence to measure the impact of chronic pain on health outcomes of Indigenous people. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 107, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Chronic Pain in Australia; Cat. no. PHE 267; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Honeyman, P.T.; Jacobs, E.A. Effects of culture on back pain in Australian aboriginals. Spine 1996, 21, 841–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, A.M.; Cross, M.J.; Hoy, D.G.; Sanchez-Riera, L.; Blyth, F.M.; Woolf, A.D.; March, L. Musculoskeletal Health Conditions Represent a Global Threat to Healthy Aging: A Report for the 2015 World Health Organization World Report on Ageing and Health. Gerontologist 2016, 56 (Suppl. 2), S243–S255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jimenez, N.; Garroutte, E.; Kundu, A.; Morales, L.; Buchwald, D. A review of the experience, epidemiology, and management of pain among American Indian, Alaska Native, and Aboriginal Canadian peoples. J. Pain 2011, 12, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, I.B.; Bunzli, S.; Mak, S.; Green, C.; Goucke, R. The unmet needs of Aboriginal Australians with musculoskeletal pain: A mixed method systematic review. Arthritis Care Res. 2017, 70, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Government Department of Health. National Strategic Action Plan for Pain Management; Australian Government Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- International Pain Summit of the International Association for the Study of Pain. Declaration of Montreal: Declaration that access to pain management is a fundamental human right. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharm. 2011, 25, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Pain Summit Initiative. National Pain Strategy; National Pain Summit Initiative: Canberra, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, M. James Cook Unversity, Singapore. 2017; Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Davy, C.; Harfield, S.; McArthur, A.; Munn, Z.; Brown, A. Access to primary health care services for Indigenous peoples: A framework synthesis. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, I.; Coffin, J.; Bullen, J.; Barnabe, C. Opportunities and challenges for physical rehabilitation with indigenous populations. Pain Rep. 2020, 5, e838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, C.; Stevens, J. Post operative pain experiences of central Australian aboriginal women. What do we understand? Aust. J. Rural. Health 2004, 12, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrigan, V.; Lewis, N.; Cass, A.; Hefler, M.; Ralph, A.P. “How can I do more?” Cultural awareness training for hospital-based healthcare providers working with high Aboriginal caseload. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, L.; Rolan, P. A systematic review of western medicine’s understanding of pain experience, expression, assessment, and management for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Pain Rep. 2019, 4, e764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queensland Health. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Capability Framework 2010–2033; Queensland Health: Brisbane, Australia, 2010.

- Craig, K.D. The social communication model of pain. Can. Psychol. 2009, 50, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amery, R. Recognising the communication gap in Indigenous health care. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 207, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, I.; O’Sullivan, P.; Coffin, J.; Mak, D.B.; Toussaint, S.; Straker, L. ‘I can sit and talk to her’: Aboriginal people, chronic low back pain and healthcare practitioner communication. Aust. Fam. Physician 2014, 43, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strong, J.; Nielsen, M.; Williams, M.; Huggins, J.; Sussex, R. Quiet about pain: Experiences of Aboriginal people in two rural communities. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2015, 23, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, A.L.; Fromme, E.K.; Meier, D.E. Training Clinicians with Communication Skills Needed to Match Medical Treatments to Patient Values. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, S435–S441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gupta, A. The importance of good communication in treating patients’ pain. AMA J. Ethics 2015, 17, 265–267. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, S.G.; Matthias, M.S. Patient-Clinician Communication About Pain: A Conceptual Model and Narrative Review. Pain Med. 2018, 19, 2154–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, I.; Green, C.; Bessarab, D. ‘Yarn with me’: Applying clinical yarning to improve clinician-patient communication in Aboriginal health care. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2016, 22, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). The National Scheme’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Cultural Safety Strategy 2020–2025. Available online: https://nacchocommunique.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-cultural-health-and-safety-strategy-2020-2025-1.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cultural Safety in Health Care for Indigenous Australians: Monitoring Framework. Cat.no. IHW 222. Canberra: AIHW. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/cultural-safety-health-care-framework (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Lin, I.; Flanangan, W. Clinical Yarning Education Project Team: Clinical Yarning Education-Development and Preliminary Evaluation of Blended Learning Program to Improve Clinical Communication in Aboriginal Health Care-Final Report; Western Australian Centre for Rural Health (WACRH), University of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ayn, C.; Robinson, L.; Matthews, D.; Andrews, C. Attitudes of dental students in a Canadian university towards communication skills learning. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 24, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, A.; Baldwin, C.; Reidlinger, D.P.; Whelan, K. Communication skills teaching for student dietitians using experiential learning and simulated patients. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet 2020, 33, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moral, R.R.; Garcia de Leonardo, C.; Caballero Martinez, F.; Monge Martin, D. Medical students’ attitudes toward communication skills learning: Comparison between two groups with and without training. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2019, 10, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thorne, S.; Kirkham, S.R.; MacDonald-Emes, J. Interpretive Description: A Noncategorical Qualitative Alternative for Developing Nursing Knowledge. Res. Nurs. Health 1997, 20, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S.; Kirkham, S.R.; O’Flynn-Magee, K. The Analytic Challenge in Interpretive Description. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2004, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bree, R.; Gallagher, G. Using Microsoft Excel to code and thematically analyse qualitative data: A simple, cost-effective approach. AISHE 2016, 8, 2811–28114. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maguire, M.; Delahunt, B. Doing thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE 2017, 9, 3351–33514. [Google Scholar]

- Kaptchuk, T.J.; Kelley, J.M.; Conboy, L.A.; Davis, R.B.; Kerr, C.E.; Jacobson, E.E.; Kirsch, I.; Schyner, R.N.; Nam, B.H.; Nguyen, L.T.; et al. Components of placebo effect: Randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ 2008, 336, 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cass, A.; Lowell, A.; Christie, M.; Snelling, P.L.; Flack, M.; Marrnganyin, B.; Brown, I. Sharing the true stories: Improving communication between Aboriginal patients and healthcare workers. Med. J. Aust. 2002, 176, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Degrie, L.; Gastmans, C.; Mahieu, L.; Dierckx de Casterle, B.; Denier, Y. How do ethnic minority patients experience the intercultural care encounter in hospitals? a systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Med. Ethics 2017, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Horvat, L.; Horey, D.; Romios, P.; Kis-Rigo, J. Cultural Competence Education for Health Professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 5, CD009405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCalman, J.; Jongen, C.; Bainbridge, R. Organisational systems’ approaches to improving cultural competence in healthcare: A systematic scoping review of the literature. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denniston, C.; Molloy, E.; Nestel, D.; Woodward-Kron, R.; Keating, J.L. Learning outcomes for communication skills across the health professions: A systematic literature review and qualitative synthesis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fallowfield, L.J.; Jenkins, V.A.; Beveridge, H.A. Truth may hurt but deceit hurtsmore: Communication in palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2002, 16, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, E.A.; Kurtz, S.; Slade, D.; Longmaid, H.E., III; Ho, M.J.; Pun, J.K.; Eggins, S.; Branch, W.T., Jr. The International Charter for Human Values in Healthcare: An interprofessional global collaboration to enhance values and communication in healthcare. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 96, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shahid, S.; Durey, A.; Bessarab, D.; Aoun, S.M.; Thompson, S.C. Identifying barriers and improving communication between cancer service providers and Aboriginal patients and their families: The perspective of service providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Queensland Govermment. The Health of Queenslanders 2020. Report of the Chief Health Officer Queensland. Available online: https://public.tableau.com/views/populationprofile/cover?:embed=y&:display=no&:showShareOptions=false&:showVizHome=no (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Little, P.; White, P.; Kelly, J.; Everitt, H.; Gashi, S.; Bikker, A.; Mercer, S. Verbal and non-verbal behaviour and patient perception of communication in primary care: An observational study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 65, e357–e365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kruske, S.; Kildea, S.; Barclay, L. Cultural safety and maternity care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Women Birth 2006, 19, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shannon, C. Social and cultural differences affect medical treatment. Aust. Fam. Physician 1994, 23, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, N.K.; Lam, P.; Castillo, E.G.; Weiss, M.G.; Diaz, E.; Alarcon, R.D.; van Dijk, R.; Rohlof, H.; Ndetei, D.M.; Scalco, M.; et al. How Do Clinicians Prefer Cultural Competence Training? Findings from the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview Field Trial. Acad. Psychiatry 2016, 40, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardes, C.M.; Ratnasekera, I.U.; Kwon, J.H.; Somasundaram, S.; Mitchell, G.; Shahid, S.; Meiklejohn, J.; O’Beirne, J.; Valery, P.C.; Powell, E. Contemporary Educational Interventions for General Practitioners (GPs) in Primary Care Settings in Australia: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, M.; Simpson-Young, V.; Paton, R.; Zuo, Y. How do GPs want to learn in the digital era? Aust. Fam. Physician 2014, 43, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristics and Previous Training | N = 64 | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Study site | ||

| A—Metropolitan | 10 | 16 |

| B—Regional | 29 | 45 |

| C—Metropolitan | 25 | 39 |

| Age 1 | ||

| 21–40 years | 32 | 50 |

| 41–60 years | 25 | 39 |

| 61–80 years | 5 | 8 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 20 | 31 |

| Female | 43 | 67 |

| Other | 1 | 2 |

| Indigenous status | ||

| Indigenous | 2 | 3 |

| Non-Indigenous | 62 | 97 |

| Profession | ||

| Medical doctors (pain medicine specialist, registrar, psychiatrist, GP senior medical officer) | 26 | 41 |

| Nursing Staff (registered nurse, clinical nurse, nurse navigator, enrolled nurse) | 13 | 20 |

| Physiotherapist | 9 | 14 |

| Psychologist | 9 | 14 |

| Pharmacist | 1 | 2 |

| Occupational Therapist | 6 | 9 |

| Previous cultural training | ||

| Yes | 47 | 73 |

| No | 17 | 27 |

| If previous cultural training—type of training | ||

| Queensland Health mandatory cultural awareness training/education packages | 32 | 68 |

| Cultural capability and safety lectures during university studies | 7 | 15 |

| Cultural awareness workshops (at Community Health Controlled Services and Remote Area Health Cops (RAHC)) | 5 | 11 |

| Not specified/unknown | 3 | 6 |

| Items | Study Site * | Score | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Low | Low | High | Very High | Combined Low | Moderate | Combined High | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1–2 | 3 | 4–5 | |||||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Perceived importance of communication training when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients | A | - | (-) | 2 | (20) | 4 | (40) | 1 | (10) | 2 | (20) | 3 | (30) | 5 | (50) |

| B | - | (-) | - | (-) | 8 | (28) | 21 | (72) | - | (-) | - | (-) | 29 | (100) | |

| C | - | (-) | 1 | (4) | 9 | (36) | 13 | (52) | 1 | (4) | 2 | (8) | 22 | (88) | |

| Total | - | (-) | 3 | (5) | 21 | (33) | 35 | (55) | 3 | (5) | 5 | (8) | 56 | (88) | |

| Perceived knowledge of how to effectively communicate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients | A | - | (-) | 2 | (20) | 3 | (30) | - | (-) | 2 | (20) | 5 | (50) | 3 | (30) |

| B | - | (-) | 1 | (3) | 8 | (28) | 2 | (7) | 1 | (3) | 18 | (62) | 10 | (35) | |

| C | 1 | (4) | 7 | (28) | 5 | (20) | - | (-) | 8 | (32) | 12 | (48) | 5 | (20) | |

| Total | 1 | (2) | 10 | (16) | 16 | (25) | 2 | (3) | 11 | (17) | 35 | (55) | 18 | (28) | |

| Perceived ability to communicate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients | A | - | (-) | - | (-) | 2 | (20) | - | (-) | - | (-) | 8 | (80) | 2 | (20) |

| B | - | (-) | - | (-) | 10 | (35) | 1 | (3) | - | (-) | 18 | (62) | 11 | (38) | |

| C | - | (-) | 4 | (16) | 3 | (12) | - | (-) | 4 | (16) | 18 | (72) | 3 | (12) | |

| Total | - | (-) | 4 | (6) | 15 | (23) | 1 | (2) | 4 | (6) | 44 | (69) | 16 | (25) | |

| Perceived confidence to communicate with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients | A | - | (-) | 1 | (10) | 1 | (10) | - | (-) | 1 | (10) | 8 | (80) | 1 | (10) |

| B | - | (-) | - | (-) | 11 | (38) | 1 | (3) | - | (-) | 17 | (59) | 12 | (41) | |

| C | - | (-) | 4 | (16) | 5 | (20) | - | (-) | 4 | (16) | 16 | (64) | 5 | (20) | |

| Total | - | (-) | 5 | (8) | 17 | (27) | 1 | (2) | 5 | (8) | 41 | (64) | 18 | (28) | |

| Occupation | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Nurse Navigator | 1 | 5 |

| Occupational Therapist | 4 | 20 |

| Pain Specialist | 6 | 30 |

| Physiotherapist | 2 | 10 |

| Psychiatrist | 1 | 5 |

| Psychologist | 3 | 15 |

| Registrar | 2 | 10 |

| GP Senior Medical Officer | 1 | 5 |

| Total | 20 | 100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernardes, C.M.; Ekberg, S.; Birch, S.; Meuter, R.F.I.; Claus, A.; Bryant, M.; Isua, J.; Gray, P.; Kluver, J.P.; Williamson, D.; et al. Clinician Perspectives of Communication with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Managing Pain: Needs and Preferences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031572

Bernardes CM, Ekberg S, Birch S, Meuter RFI, Claus A, Bryant M, Isua J, Gray P, Kluver JP, Williamson D, et al. Clinician Perspectives of Communication with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Managing Pain: Needs and Preferences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031572

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernardes, Christina M., Stuart Ekberg, Stephen Birch, Renata F. I. Meuter, Andrew Claus, Matthew Bryant, Jermaine Isua, Paul Gray, Joseph P. Kluver, Daniel Williamson, and et al. 2022. "Clinician Perspectives of Communication with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Managing Pain: Needs and Preferences" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031572

APA StyleBernardes, C. M., Ekberg, S., Birch, S., Meuter, R. F. I., Claus, A., Bryant, M., Isua, J., Gray, P., Kluver, J. P., Williamson, D., Jones, C., Houkamau, K., Taylor, M., Malacova, E., Lin, I., & Pratt, G. (2022). Clinician Perspectives of Communication with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Managing Pain: Needs and Preferences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031572