Acceptance Mindfulness-Trait as a Protective Factor for Post-Natal Depression: A Preliminary Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

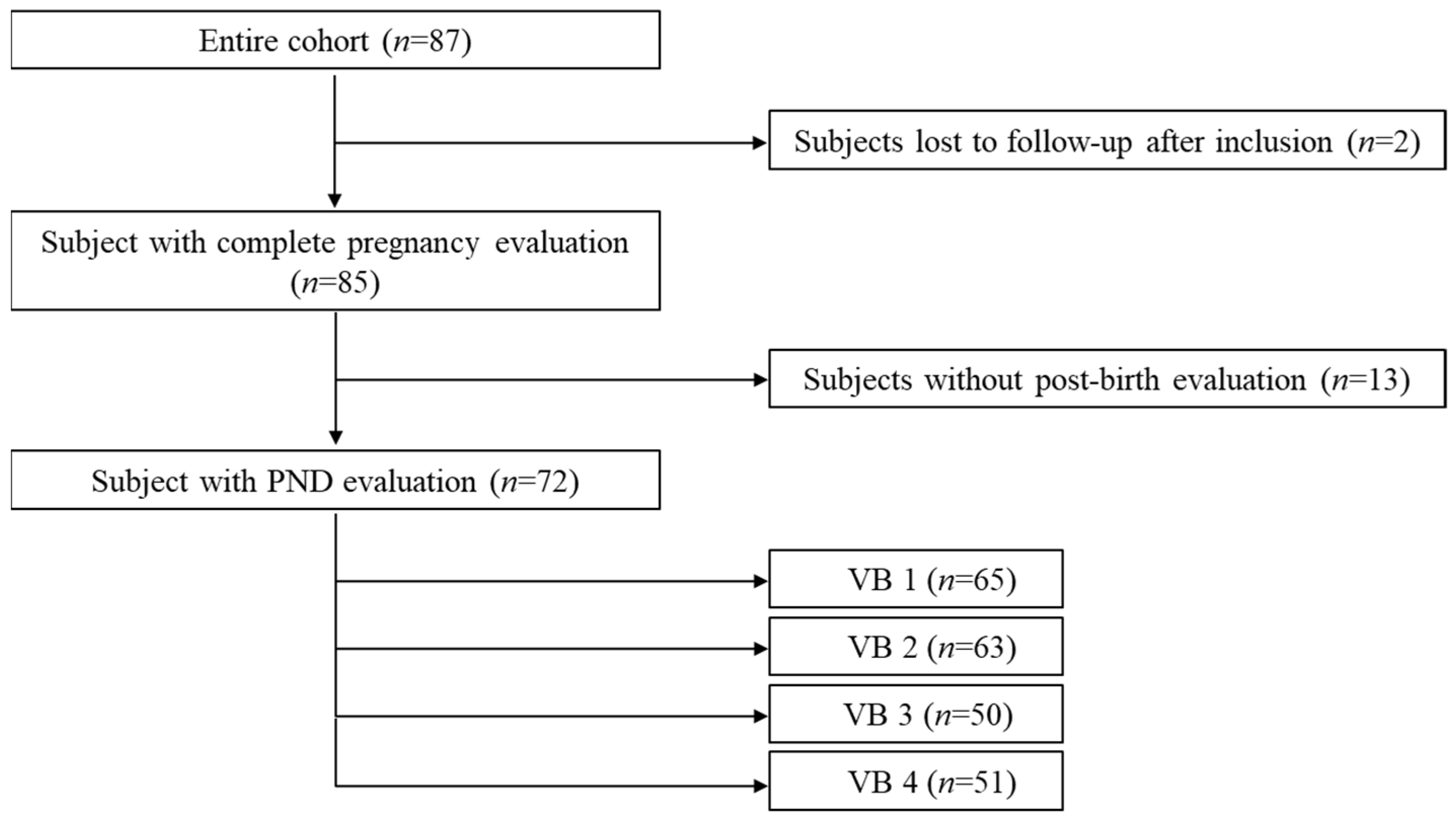

2.1. Participants

2.2. Protocole

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Data

2.3.2. Three Main Questionnaires

- For the PND status: PND was assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) with a screening cut-off >11 [41]. French validation showed good psychometric qualities [42]. The EPDS is a 10-item self-report questionnaire assessing the symptoms of depression and anxiety. Each self-descriptive statement about the 7 last days was evaluated using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no change from usual) to 3 (an important change from usual). It was fulfilled four times at VB1, VB2, VB3 and VB4.

- For the mindfulness evaluation: the 14-item, self-administered Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory short form (FMI short form) assessed mindfulness [25] developed for people without any background knowledge in mindfulness [25]. French validation showed good psychometric qualities [43]. It constitutes a consistent and reliable scale evaluating several important aspects of mindfulness, which indexes trait mindfulness as presence and nonjudgmental acceptance [25]. Each self-descriptive statement was evaluated using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Depending on the suggested time frame, state-and trait-like components could be assessed. In the present study, the short form was used for measuring MT. It was fulfilled once at VIN.

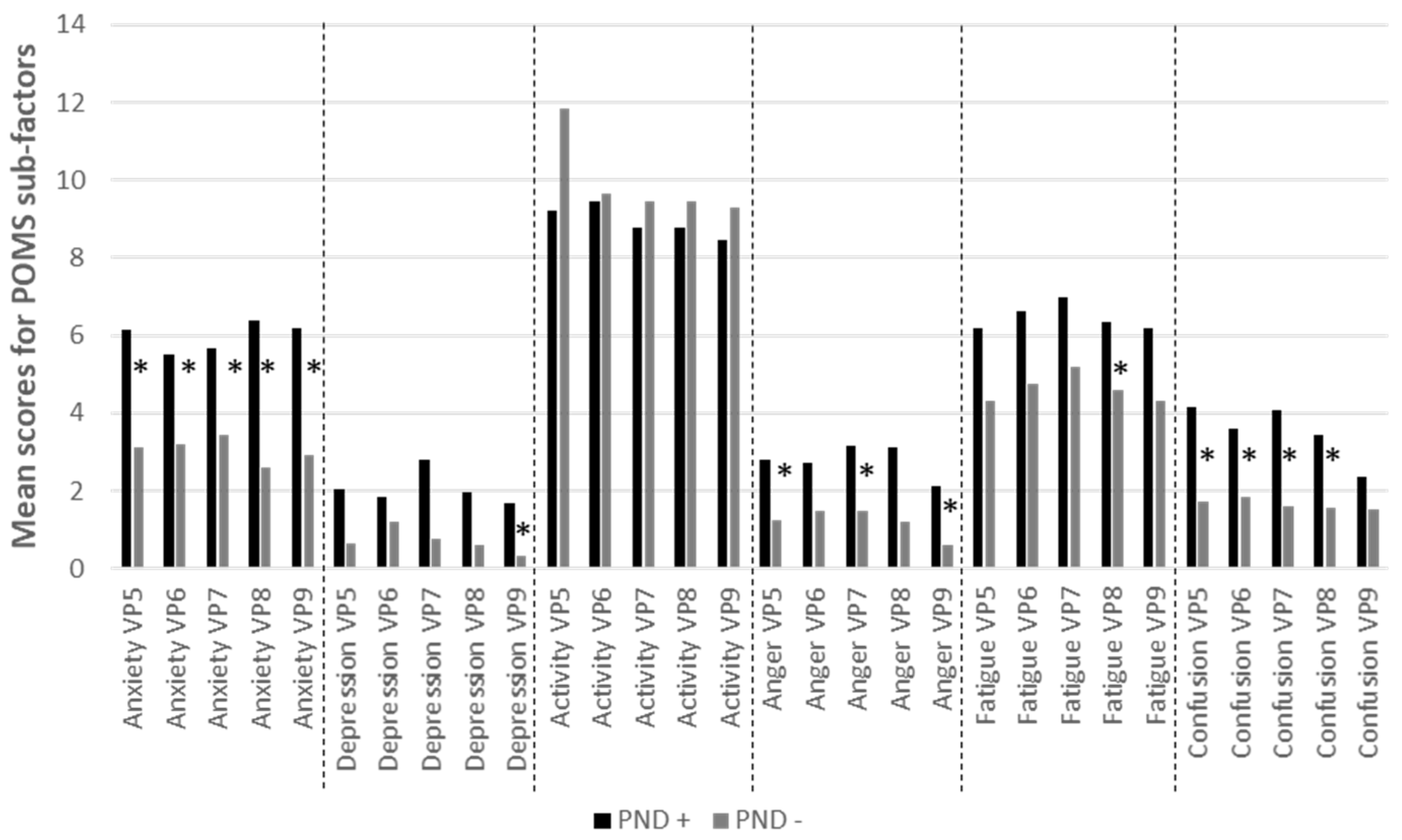

- For the mood follow-up: The mood was evaluated at the beginning of both sessions using an abbreviated version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) [44]. French version replicated the English initial validation [45]. Abbreviated version of the POMS consisted in an adjective checklist of 37 items rated on a five-point scale that ranges from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The subjects were asked to answer according to their present mood. Six factors were then calculated: anxiety-tension, depression-dejection, anger-hostility, fatigue-inertia, vigor-activity and confusion-bewilderment. It was fulfilled during the pregnancy from VI to VP9, unless the woman gave birth before 9 months of pregnancy. Given that pregnancy produce a multitude of affective changes, the use of multidimensional mood model (not only positive or negative), as the POMS does, appears relevant.

2.3.3. Four Questionnaires for the General Psychological Functioning

- Cloninger’s Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised (TCI-R) short-version is a 56 items self-report questionnaire with 5-grade Likert scale responses ranging from definitely false to true [46,47,48]. It is intended to assess the individual differences of the four temperaments (Harm Avoidance, Novelty Seeking, Reward Dependence and Persistence) and three character higher-order dimensions (Self-Directedness, Cooperativeness and Self- Transcendence). Each higher order dimension is further divided into sub-scales. It is considered as a useful instrument to assess Cloninger’s model of the 7 dimensions of personality in non-clinical samples [46,47,48].

- Anxiety-trait level was assessed using the French version of the Spielberger State-Trait-Anxiety Inventory (S-STAI; [49,50]). The 20 items of the trait subscale ask subjects to indicate the intensity of their anxiety in general. In this study and the sample was categorized in three groups according to their score [36]: women with a high score (score > 65), women with a middle score of trait-anxious-trait (56 < score ≤ 65), and women with a low score (score < 56).

- The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS, [51,52]) covers both hedonic constructs including the subjective experience of happiness and life satisfaction, and eudaemonic constructs addressing psychological functioning and self-realization in the previous two weeks [51]. It comprises 14 items and responses are made on a 5-point scale ranging from “none of the time” to “all of the time”. The scale is suitable for monitoring mental well-being in healthy populations as it shows few ceiling or floor effects [51].

- The Symptom Checklist-90 revised (SCL90R, [53]), is a common mental health evaluation tool used to assess psychological problems. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (extremely”) based on how much an individual was bothered by each item in the last weeks. Five symptoms’ dimensions were evaluated: somatization—, obsessive-compulsive—OC, interpersonal sensitivity—IS, depression—D, and anxiety—A.

- Four homemade analogic visual scales (from 0 “very bad/low” to 10 “very good/high”) were used for quality of life assessment: (1) ”in the past month, how would you rate the quality of your sleep?”, (2) “in the past month, how would you rate your stress level at work?”, (3) “ in the past month, how would you rate your level of stress at home?” and (4) “in the past month, how would you rate your level of apprehension about giving birth?”

2.3.4. Four Questionnaires for the Specific Pregnancy and Delivery Psychological Functioning

- The Prenatal Attachment Inventory (PAI, [54]) is a 21 items questionnaire for expectant mothers which assess maternal-fetal attachment defined as the strength of mothers’ emotional ties with the fetus (and also known as prenatal bonding. It captures variability in expectant mothers’ behaviours, cognitions and emotions towards the fetus, which appear important for positive prenatal health practices [55]. Expectant women were asked to assess how often they engaged in specific thoughts or behaviours towards the fetus on a 4-point scale (1 « almost never » to 4 « almost always »).

- The Questionnaire de Dépistage Anténatal du risque de Dépression du Postpartum (DAD-P; postpartum Depression Risk Screening Questionnaire), previously named le Questionnaire de Genève, was used to detect women at risk to develop PND already during pregnancy [56]. It is based on 10 items, six for screening, and four supplementary items for optimizing the screening leading to several screening strategies, depending on whether broad or targeted screening is.

- The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is a 12 items questionnaire assessing the perceived social support from three sources: Family, Friends, and a Significant Other [57]. A seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (7)” was used with a total score obtained by adding the score for each statement, divided by the total number of statements. It was validated for expectant women [58].

- The Labour Agentry Scale (LAS) is a 29 items instrument measuring expectancies and experiences of personal control during childbirth [59]. It consists of short affirmative statements (e.g., ‘I felt confident’ and ‘I felt tense’). Women were asked to rate each statement on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (representing rarely) to 7 (representing almost always).

2.3.5. Three Questionnaires for Delivery Trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- The traumatic event scale (TES) was a 21 items questionnaire developed in accordance with DSM-IV criteria for the PTSD syndrome and comprises all the DSM-IVR symptoms and criteria of PTSD [60,61]. The TES was divided on two parts: the part one (TES 1) quantifies frequency and severity of single posttraumatic stress symptoms focusing on childbird; part two (TES 2) assesses how each of the 21 symptoms impacts the daily quality of life.

- The Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire (PDEQ) is 10-items self-questionnaire assessing peritraumatic dissociation that occurred at the time of a trauma [62,63]. Dissociation is well-recognized as a risk factor for developing PTSD. A five-point Likert-type scale ranging from “not true (1)” to “totally true (5)” was used. A score greater than or equal to 22 attests to the presence of clinically significant peri-traumatic dissociation [64].

- The traumatic impact of childbirth questionnaire (ITA) assesses the recollection of experience during labour and delivery. It is constituted first, by 18 items rated from 1 to 7 (ITA-1), then, by 14 items rated from 1 to 6(ITA-2). This specific questionnaire has not yet been validated.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population

3.2. PND

3.3. Risk Factors for the PND

3.4. Mood Evolution during the Pregnancy According to PND Status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martínez-Borba, V.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Osma, J.; Andreu-Pejó, L. Predicting Postpartum Depressive Symptoms from Pregnancy Biopsychosocial Factors: A Longitudinal Investigation Using Structural Equation Modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woody, C.A.; Ferrari, A.J.; Siskind, D.J.; Whiteford, H.A.; Harris, M.G. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 219, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Maternal Mental Health and Child Development in Low and Middle-Income Countries. 2008. Available online: www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/mmh_jan08_meeting_report.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Slomian, J.; Honvo, G.; Emonts, P.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health 2019, 15, 1745506519844044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moraes, G.P.; Lorenzo, L.; Pontes, G.A.; Montenegro, M.C.; Cantilino, A. Screening and diagnosing postpartum depression: When and how? Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2017, 39, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Loomans, E.M.; van Dijk, A.E.; Vrijkotte, T.G.; van Eijsden, M.; Stronks, K.; Gemke, R.J.; Van den Bergh, B.R. Psychosocial stress during pregnancy is related to adverse birth outcomes: Results from a large multi-ethnic community-based birth cohort. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meltzer-Brody, S.; Howard, L.M.; Bergink, V.; Vigod, S.; Jones, I.; Munk-Olsen, T.; Honikman, S.; Milgrom, J. Postpartum psychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, S.S.H.; Zijlmans, M.A.C.; Cillessen, A.H.N.; De Weerth, C. Maternal prenatal and early postnatal distress and child stress responses at age 6. Stress 2019, 22, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/lit_review_postpartum_depression.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Walsh, K.; Mccormack, C.A.; Webster, R.; Pinto, A.; Lee, S.; Feng, T.; Krakovsky, H.S.; O’Grady, S.M.; Tycko, B.; Champagne, F.A.; et al. Maternal prenatal stress phenotypes associate with fetal neurodevelopment and birth outcomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23996–24005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, D.E.; Vigod, S.N. Postpartum Depression: Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Emerging Therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 2019, 70, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldar, E.; Rutledge, R.B.; Dolan, R.J.; Niv, Y. Mood as Representation of Momentum. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raoult, C.M.C.; Moser, J.; Gygax, L. Mood as Cumulative Expectation Mismatch: A Test of Theory Based on Data from Non-verbal Cognitive Bias Tests. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wong, M.Y. Towards a theory of mood function. Philos. Psychol. 2016, 29, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreher, J.B.; Schwartz, J.B. Overtraining syndrome: A practical guide. Sports Health 2012, 4, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vrijkotte, S.; Roelands, B.; Pattyn, N.; Meeusen, R. The Overtraining Syndrome in Soldiers: Insights from the Sports Domain. Mil. Med. 2019, 184, e192–e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorenson, D.L. Uncertainty in pregnancy. Naacog’s Clin. Issues Perinat. Women’s Health Nurs. 1990, 1, 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sevil Degirmenci, S.; Kosger, F.; Altinoz, A.E.; Essizoglu, A.; Aksaray, G. The relationship between separation anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in pregnant women. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 2927–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperry, S.H.; Walsh, M.A.; Kwapil, T.R. Emotion dynamics concurrently and prospectively predict mood psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 261, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bei, B.; Coo, S.; Trinder, J. Sleep and Mood during Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Sleep Med. Clin. 2015, 10, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillerer, K.M.; Neumann, I.D.; Slattery, D.A. From stress to postpartum mood and anxiety disorders: How chronic peripartum stress can impair maternal adaptations. Neuroendocrinology 2012, 95, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are; Hyperion Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, P.; Niemann LSchmidt, S.; Walach, H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 57, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.; Jha APDunne, J.D.; Saron, C.D. Investigating the Phenomenological Matrix of Mindfulness-related Practices from a Neurocognitive Perspective. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 632–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walach, H.; Buchheld, N.; Buttenmüller, V.; Kleinknecht, N.; Schmidt, S. Measuring mindfulness—the Freiburg mindfulness inventory (FMI). Pers. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.M.; Feldman, G. Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 11, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, L.; Toney, L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hanley, A.W.; Garland, E.L. The mindful personality: A meta-analysis from a cybernetic perspective. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1456–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhofer, T.; Duggan, D.S.; Griffith, J.W. Dispositional mindfulness moderates the relation between neuroticism and depressive symptoms. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 958–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giluk, T.L. Mindfulness, Big Five personality, and affect: A meta-analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsbosch, L.P.; Boekhorst, M.G.B.M.; Potharst, E.S.; Pop, V.J.M.; Nyklíček, I. Trait mindfulness during pregnancy and perception of childbirth. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2021, 24, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2006, 10, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, J.; Baer, R.A. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 31, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Sawyer, A.T.; Witt, A.A.; Oh, D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 78, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenthaler, L.; Turba, J.D.; Tran, U.S. Emotion regulation mediates the associations of mindfulness on symptoms of depression and anxiety in the general population. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hall, H.G.; Beattie, J.; Lau, R.; East, C.; Anne Biro, M. Mindfulness and perinatal mental health: A systematic review. Women Birth 2016, 29, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matvienko-Sikar, K.; Lee, L.; Murphy, G.; Murphy, L. The effects of mindfulness interventions on prenatal well-being: A systematic review. Psychol. Health 2016, 31, 1415–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Q.; Bazzano, A.N.; Cao, F. Effectiveness of Smartphone-Based Mindfulness Training on Maternal Perinatal Depression: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhouse, H.; Mercuri, K.; Judd, F.; Brown, S.J. Antenatal mindfulness intervention to reduce depression, anxiety and stress: A pilot randomised controlled trial of the MindBabyBody program in an Australian tertiary maternity hospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guedeney, N.; Fermanian, J. Validation study of the French Version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): New results about use and psychometric properties. Eur. Psychiatry 1998, 13, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trousselard, M.; Steiler, D.; Raphel, C.; Cian, C.; Duymedjian, R.; Claverie, D.; Canini, F. Validation of a French version of the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory-short version: How mindfulness deals with the stress in a working middle-aged opulation. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2010, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shacham, S. A shortened version of profile of mood states. J. Pers. Assess. 1983, 47, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillion, L.; Gagnon, P. French Adaptation of the Shortened Version of the Profile of Mood States. Psychol. Rep. 1999, 84, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloninger, C.R.; Svrakic, D.M.; Przybeck, T.R. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1993, 50, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloninger, C.R.; Svrakic, N.M.; Svrakic, D.M. The Role of personality self-organization in development of mental order and disorder. Dev. Psychopathol. 1997, 9, 881–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, A.; Serra-Grabulosa, J.M.; Natale, V. A reduced Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-56). Psychometric properties in a non-clinical sample. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C. Manual for the State-Trait-Anxiety Inventory: STAI (Form Y); Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Smith, L.H. Anxiety (drive), stress, and serial-position effects in serial-verbal learning. J. Exp. Psychol. 1966, 72, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trousselard, M.; Canini, F.; Dutheil, F.; Claverie, D.; Fenouillet, F.; Naughton, G.; Steward-Brown, S.; Franck, N. Investigating well-being in healthy population and schizophrenia with the WEMWBS. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 245, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Lipman, R.S.; Rickels, K.; Uhlenhuth, E.H.; Covi, L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behav. Sci. 1974, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, M.E. Development of the Prenatal Attachment Inventory. West J. Nurs. Res. 1993, 15, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, S.; Hughes, C. Great expectations? Do mothers’ and fathers’ prenatal thoughts and feelings about the infant predict parent-infant interaction quality? A meta-analytic review. Dev. Rev. 2018, 48, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righetti-Veltema, M.; Conne-Perréard, E.; Bousquet, A.; Manzano, J. Construction et validation multicentrique d’un questionnaire prépartum de dépistage de la dépression postpartum. Psychiatr. Enfant. 2007, 49, 513–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denis, A.; Callahan, S.; Bouvard, M. Evaluation of the French version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support during the postpartum period. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodnett, E.D.; Simmons-Tropea, D.A. The Labour Agentry Scale: Psychometric properties of an instrument measuring control during childbirth. Res. Nurs. Health 1987, 10, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijma, K.; Söderquist, J.; Wijma, B. Posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth: A cross sectional study. J. Anxiety Disord. 1997, 11, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; Autho: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Marmar, C.R.; Weiss, D.S.; Metzler, T.J. The Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; Wilson, J.P., Marmar, C.R., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 412–428. [Google Scholar]

- Birmes, P.; Brunet, A.; Benoit, M.; Defer, S.; Hatton, L.; Sztulman, H.; Schmitt, L. Validation of the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire self-report version in two samples of French-speaking individuals exposed to trauma. Eur. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmes, P.; Carreras, D.; Ducassé, J.-L.; Charlet, J.-P.; Warner, B.A.; Lauque, D.; Schmitt, L. Peritraumatic Dissociation, Acute Stress, and Early Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Victims of General Crime. Can. J. Psychiatry 2001, 46, 649–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohls, N.; Sauer, S.; Walach, H. Facets of mindfulness–Results of an online study investigating the Freiburg mindfulness inventory. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menges, J.; Caltabiano, M. The effect of mindfulness on academinc self-efficcacy: A randomosed controlled trial. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Couns. 2019, 4, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Neff, K. Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy Attitude Toward Oneself. Self Identity 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arch, J.J.; Brown, K.W.; Dean, D.J.; Landy, L.N.; Brown, K.; Laudenslager, M.L. Self-compassion training modulates alpha-amylase, heart rate variability, and subjective responses to social evaluative threat in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 42, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, L.; Bryant, C.; Brown, V.; Bei, B.; Judd, F. Self-compassion, attitudes to ageing and indicators of health and well-being among midlife women. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.; Klibert, J.J.; Tarantino, N.; Lamis, D.A. Savouring and Self-compassion as Protective Factors for Depression: Protective Factors for Depression. Stress Health 2017, 33, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, S.; Walach, H.; Schmidt, S.; Hinterberger, T.; Horan, M.; Kohls, N. Implicit and explicit emotional behavior and mindfulness. Conscious. Cogn. 2011, 20, 1558–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, E.J.; Fawcett, J.M.; Mazmanian, D. Risk of obsessive compulsive disorder in pregnant and postpartum women: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Sommerdyk, C. Obsessive–compulsive disorder in the postpartum period: Diagnosis, differential diagnosis and management. Women’s Health 2015, 11, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Findley, D.B.; Leckman, J.F.; Katsovich, L.; Lin, H.; Zhang, H.; Grantz, H.; Otka, J.; Lombroso, P.J.; King, R.A. Development of the Yale Children’s Global Stress Index (YCGSI) and its application in children and adolescents with Tourette’s syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, J.; Cervera, M.; Osejo, E.; Salamero, M. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in childhood and adolescence: A clinical study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1992, 33, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, G.M. The overlap between anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 17, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.S.; Chu, C.; Gollan, J.; Gossett, D.R. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms during the postpartum period. A prospective cohort. J. Reprod. Med. 2013, 58, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Broekhoven, K.E.M.; Karreman, A.; Hartman, E.E.; Lodder, P.; Endendijk, J.J.; Bergink, V.; Pop, V.J.M. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder symptoms as a risk factor for postpartum depressive symptoms. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2019, 22, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barcaccia, B.; Tenore, K.; Mancini, F. Early childhood experiences shaping vulnerability to Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2015, 12, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Yorulmaz, O.; Gençöz, T.; Woody, S. Vulnerability factors in OCD symptoms: Cross-cultural comparisons between Turkish and Canadian samples. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2010, 17, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, C.; Hall, G.; Soares, C.N.; Steiner, M. Physiological stress response in postpartum women with obsessive—Compulsive disorder: A pilot study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musser, E.D.; Ablow, J.C.; Measelle, J.R. Predicting maternal sensitivity: The roles of postnatal depressive symptoms and parasympathetic dysregulation. Infant Ment. Health J. 2012, 33, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Balsamo, M. Anger and depression: Evidence of a possible mediating role for rumination. Psychol. Rep. 2010, 106, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascenzo, N.; Collard, J.J. Anger, forgiveness, and depression in the postnatal experience. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 2018, 13, 689–698. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, A.; Laganà, A.S.; Leonardi, V.; Greco, D.; Merlino, M.; Vitale, S.G.; Triolo, O.; Zoccali, R.A.; Muscatello, M.R.A. Inside–out: The role of anger experience and expression in the development of postpartum mood disorders. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2018, 31, 3033–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.H.; Hall, W.A. Anger in the context of postnatal depression: An integrative review. Birth 2018, 45, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobe, H.; Kita, S.; Hayashi, M.; Umeshita, K.; Kamibeppu, K. Mediating effect of resilience during pregnancy on the association between maternal trait anger and postnatal depression. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 102, 152190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Velting, D.; et al. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, S.M.; Garofalo, C.; Velotti, P. Emotion regulation, mindfulness, and alexithymia: Specific or general impairments in sexual, violent, and homicide offenders? J. Crim. Justice 2018, 58, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C.; Gillespie, S.M.; Velotti, P. Emotion regulation mediates relationships between mindfulness facets and aggression dimensions. Aggress. Behav. 2020, 46, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cludius, B.; Mannsfeld, A.K.; Schmidt, A.F.; Jelinek, L. Anger and aggressiveness in obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and the mediating role of responsibility, non-acceptance of emotions, and social desirability. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 271, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J.; Lipworth, L.; Burney, R. The Clinical Use of Mindfulness Meditation for the Self-Regulation of Chronic Pain. J. Behav. Med. 1985, 8, 163–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A.; Serretti, A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: A review and meta-analysis. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009, 15, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnberg, G.; Nissen, E.; Niemi, M. What is learned from Mindfulness Based Childbirth and Parenting Education?—Participants’ experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations preliminary results. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1982, 4, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Z.V.; Williams, J.M.G.; Teasdale, J.D. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; p. 351. [Google Scholar]

- Flaxman, P.E.; Bond, F.W. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in the Workplace. In Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches: Clinician’s Guide to Evidence Base and Applications; Baer, R.A., Ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1st Trimester | 2nd Trimester | 3rd Trimester | Delivery | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| Visit | VI | VP5 | VP6 | VP7 | VP8 | VP9 | VB1 | VB2 | VB3 | VB4 | ||||||||||||

| Pregnancy | Post-Birth | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion Visit VI First Trimester | Monthly Visit During Trimester 2 and 3 | Follow-Up Visit Post Delivery | |||||||||

| VP5 | VP6 | VP7 | VP8 | VP9 | VB1 | VB2 | VB3 | VB4 | |||

| Regulatory information | Notice—Consent form | x | |||||||||

| Keys-questionnaires | Socio-demographic information | x | |||||||||

| FMI | x | ||||||||||

| POMS | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| EPDS | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| General psychological functioning | TCI-R | x | |||||||||

| STAI | x | ||||||||||

| WEMWBM | x | ||||||||||

| SCL-90 | x | ||||||||||

| QoL | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Specific psychological pregnancy and delivery functioning | PAI | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| DAD-P | x | ||||||||||

| MSPSS | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| LAS | x | ||||||||||

| Trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaires | TES | x | |||||||||

| PDEQ | x | ||||||||||

| ITA | x | ||||||||||

| Duration of questionnaires (minutes) | 120 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.4 +/− 4.5 years (29.0–35.0) | ||

| Pregnancy Age at the Inclusion | 16.7 Weeks of Amenorrhea (WA) +/−2.0 WA (15.2–18.0 WA) | ||

| n | % | ||

| Site repartition | Paris | 43 | 50.6 |

| Bordeaux | 32 | 37.6 | |

| Metz | 10 | 11.8 | |

| Marital status | Couple | 81 | 96.4 |

| Couple but single living | 3 | 3.6 | |

| Geographical celibacy | 1 | 0.01 | |

| Missing data | 1 | 0.01 | |

| Historic of psychological care | Psychological support | 51 | 60 |

| No psychological support | 34 | 40 | |

| Number of children | No child | 57 | 67.9 |

| One child | 22 | 26.2 | |

| Two or more children | 6 | 6 | |

| Previous pregnancies | None | 48 | 56.5 |

| Previous pregnancy * | 15 | 17.6 | |

| Two or more pregnancies | 22 | 25.8 | |

| Type of pregnancy | Spontaneous | 79 | 92.9 |

| Medically assisted reproduction: | 6 | 7.1 | |

| Desired pregnancy | Yes | 74 | 88.1 |

| No | 10 | 11.9 | |

| Missing data | 1 | 0.01 | |

| Variables | DPN + Mean (SD) | DPN − Mean (SD) | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freiburg Mindfulness Questionnaire (FMI) | Presence | 17.5(3) | 18(2.6) | 0.52 |

| Acceptance | 19.6(3.1) | 212(3.5) | 0.003 | |

| Total | 37.1(5) | 40(5.3) | 0.03 | |

| Profile of Mood Scale (POMS) | Anxiety-tension | 6(5.5) | 3.8(3.8) | 0.08 |

| Anger-hostility | 3.2(3.7) | 1.8(3.7) | 0.11 | |

| Depression | 1.7(2.22) | 1.3(2.5) | 0.5 | |

| Fatigue-inertia | 5.5(4.7) | 5(3.8) | 0.63 | |

| Activity-vigor | 11.3(4.1) | 11.8(3.8) | 0.6 | |

| Confusion-bewilderment | 3(3) | 1.5(1.9) | 0.03 |

| Sessions | Variables * | Odds-Ratio | IC 95 % | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VI | FMI_acceptance | 0.9 | 0.66–0.93 | 0.003 |

| FMI_total | 0.90 | 0.80–0.99 | 0.025 | |

| TCI_ Self-Directedness | 1.14 | 1.03–1.26 | 0.010 | |

| TCI_ Cooperativeness | 1.13 | 0.97–1.35 | 0.120 | |

| POMS_tension_anxiety | 1.11 | 1.00–1.25 | 0.050 | |

| POMS_ anger-hostility | 1.11 | 0.98–1.28 | 0.110 | |

| POMS_ confusion-bewilderment | 1.29 | 1.05–1.63 | 0.013 | |

| STAI-Trait | 0.034 | |||

| Very low | — | — | ||

| Low | 4.52 | 1.25–21.76 | 0.033 | |

| Middle | 8.87 | 1.80–54.92 | 0.011 | |

| High | 6.33 | 0.21–194.45 | 0.232 | |

| WEMWBS | 0.94 | 0.87–1.02 | 0.127 | |

| SCL_obsessive-compulsive, | 4.21 | 1.75–11.93 | 0.001 | |

| SCL_ interpersonal sensitivity | 2.57 | 1.03–7.34 | 0.042 | |

| SCL_depression | 3.21 | 1.39–8.67 | 0.005 | |

| SCL_anxiety | 2.32 | 1.00–6.20 | 0.050 | |

| SCL_hostility | 3.28 | 1.13–11.11 | 0.028 | |

| SCL_Phobic anxiety | 4.12 | 0.57–40.20 | 0.160 | |

| SCL_Paranoid ideation | 2.71 | 0.76–10.86 | 0.124 | |

| SCL_Psychoticism | 5.30 | 1.49–32.65 | 0.005 | |

| SCL_General Severity Index | 6.38 | 1.76–31.34 | 0.003 | |

| SCL_Positive Symptom Total | 1.04 | 1.01–1.08 | 0.012 | |

| SCL_, Positive Symptom Distress Index | 0.72 | 0.52–0.93 | 0.012 | |

| MSPSS_Friends | 0.70 | 0.41–1.16 | 0.165 | |

| MSPSS_total | 0.61 | 0.32–1.11 | 0.104 | |

| QoL_ level of stress at work | 1.16 | 1.01–1.38 | 0.038 | |

| Age | 0.93 | 0.82–1.03 | 0.178 | |

| History of psychological care | 0.006 | |||

| No | — | — | ||

| Yes | 4.06 | 1.50–11.62 | 0.006 | |

| Number of children | 0.018 | |||

| 0 | — | — | ||

| 1 | 0.30 | 0.06–1.07 | 0.086 | |

| More than 2 | 6.44 | 0.87–131.50 | 0.108 | |

| VG ** | POMS_tension_anxiety | 1.41 | 1.15–1.79 | <0.001 |

| Prenatal Attachment Inventory | 0.94 | 0.88–1.00 | 0.066 | |

| MSPSS_Friends | 0.67 | 0.38–1.12 | 0.128 | |

| MSPSS_total | 0.57 | 0.29–1.09 | 0.088 | |

| QoL_ quality of sleep | 0.77 | 0.58–0.98 | 0.037 | |

| QoL_level of stress at work | 1.25 | 1.02–1.56 | 0.029 | |

| QoL_level of stress at home | 1.49 | 1.15–2.01 | 0.002 | |

| PND Risk Screening Questionnaire | 0.175 | |||

| Having no risk | — | — | ||

| Having a risk | 3.47 | 0.57–23.78 | 0.180 | |

| VP1 | Traumatic event scale 1 | 1.16 | 0.99–1.39 | 0.068 |

| Traumatic event scale 2 | 1.31 | 1.12–1.62 | <0.001 | |

| ITA_1 | 1.07 | 1.03–1.12 | <0.001 | |

| ITA_2 | 1.09 | 1.03–1.18 | 0.003 | |

| Labour Agentry | 0.90 | 0.84–0.95 | <0.001 | |

| Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences | 0.001 | |||

| Score < 22 | — | — | ||

| Score ≥ 22 | 7.33 | 2.12–34.55 | 0.004 |

| Variables | OR * | CI 95% ** | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FMI_acceptance (VI) | 0.79 | 0.66–0.93 | 0.003 |

| SCL_obsessive-compulsive (VI) | 4.21 | 1.75–11.93 | 0.001 |

| Having an history of psychological care (VI) | 4.06 | 1.50–11.62 | 0.006 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tharwat, D.; Trousselard, M.; Fromage, D.; Belrose, C.; Balès, M.; Sutter-Dallay, A.-L.; Ezto, M.-L.; Hurstel, F.; Harvey, T.; Martin, S.; et al. Acceptance Mindfulness-Trait as a Protective Factor for Post-Natal Depression: A Preliminary Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031545

Tharwat D, Trousselard M, Fromage D, Belrose C, Balès M, Sutter-Dallay A-L, Ezto M-L, Hurstel F, Harvey T, Martin S, et al. Acceptance Mindfulness-Trait as a Protective Factor for Post-Natal Depression: A Preliminary Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031545

Chicago/Turabian StyleTharwat, Dahlia, Marion Trousselard, Dominique Fromage, Célia Belrose, Mélanie Balès, Anne-Laure Sutter-Dallay, Marie-Laure Ezto, Françoise Hurstel, Thierry Harvey, Solenne Martin, and et al. 2022. "Acceptance Mindfulness-Trait as a Protective Factor for Post-Natal Depression: A Preliminary Research" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031545

APA StyleTharwat, D., Trousselard, M., Fromage, D., Belrose, C., Balès, M., Sutter-Dallay, A.-L., Ezto, M.-L., Hurstel, F., Harvey, T., Martin, S., Vigier, C., Spitz, E., & Duffaud, A. M. (2022). Acceptance Mindfulness-Trait as a Protective Factor for Post-Natal Depression: A Preliminary Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031545