Mobile Dating Applications and the Sexual Self: A Cluster Analysis of Users’ Characteristics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

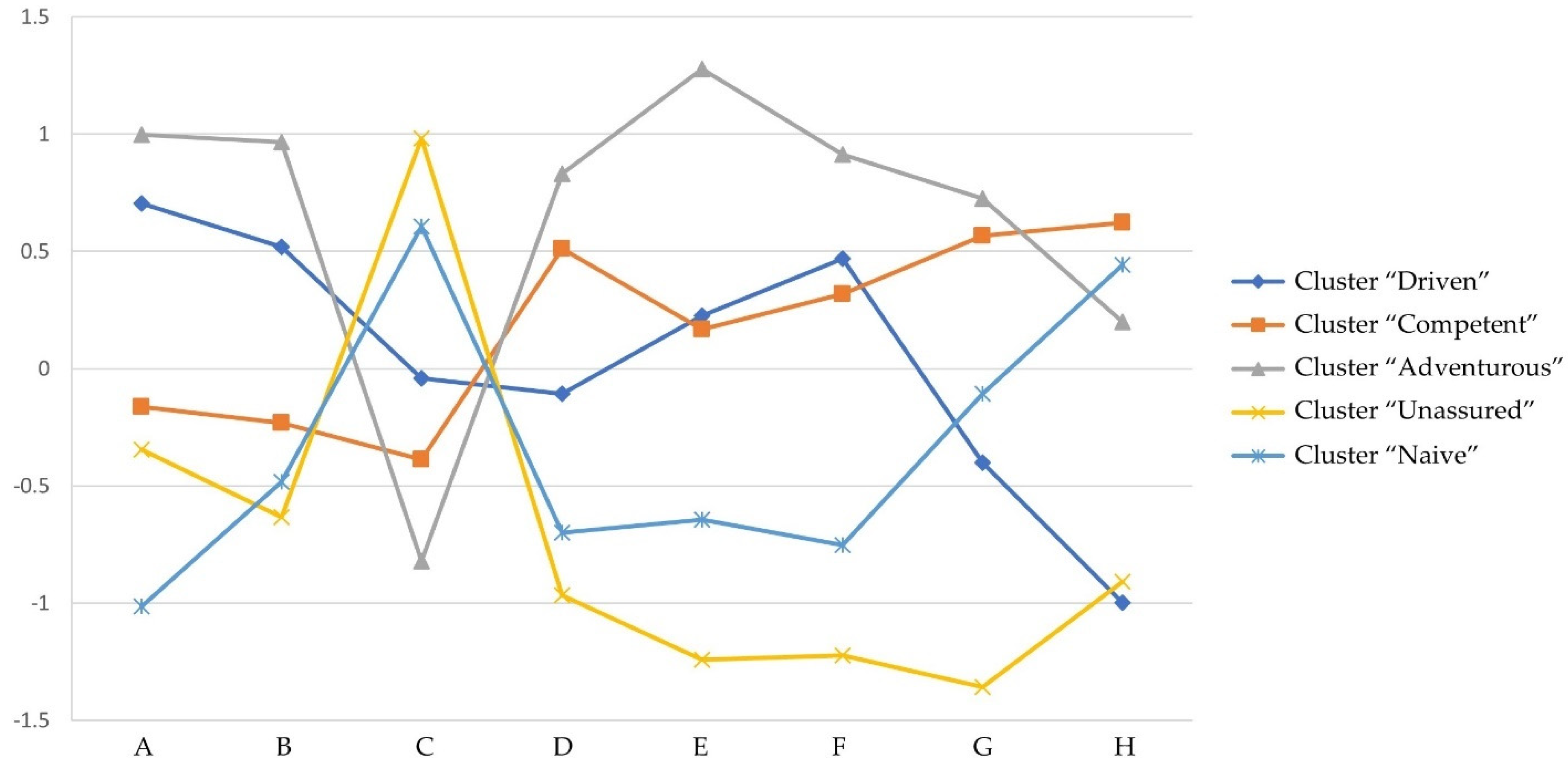

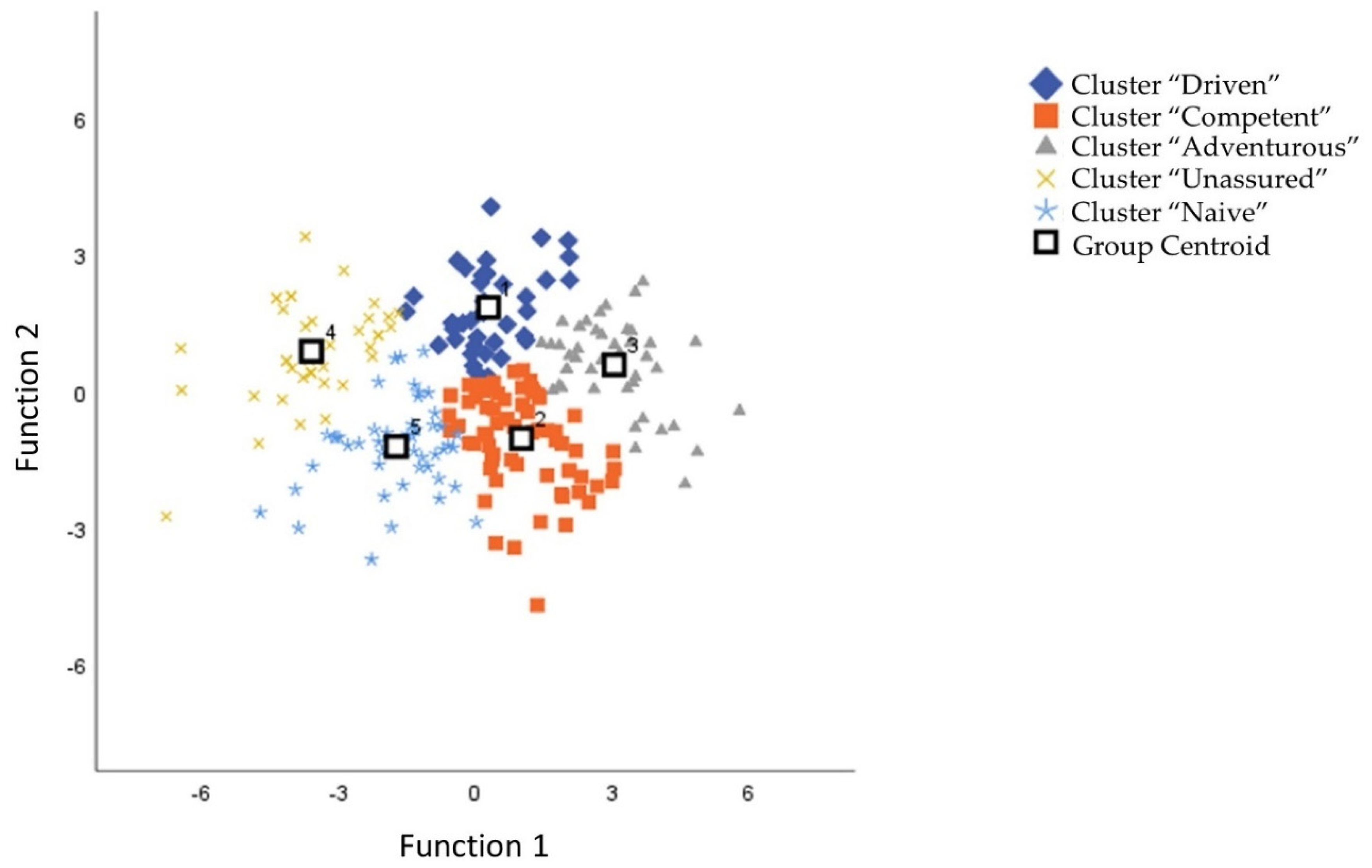

3.1. Cluster Analyses

3.2. Cluster Description

3.3. Cluster Comparisons

4. Discussion

4.1. Contribution

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J. Online Communication Among Adolescents: An Integrated Model of Its Attraction, Opportunities, and Risks. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 48, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petre, C.E. The relationship between Internet use and self-concept clarity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2021, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, L.R.; Magnusson, D. Stability and change in patterns of extrinsic adjustment problems. In Problems and Methods in Longitudinal Research: Stability and Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.M.; McClelland, S.I.; Clark, J.B.; Boylan, E.A. Phenomenological Research Methods in the Psychological Study of Sexuality; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, A.R.; Hoffman, L.; Wilcox, B.L. Sexual Self-Concept: Testing a Hypothetical Model for Men and Women. J. Sex Res. 2013, 51, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmel, M.S. The Sexual Self: The Construction of Sexual Scripts; Vanderbilt University Press: Nashville, TN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky, S.S.; Dekhtyar, O.; Cupp, P.K.; Anderman, E.M. Sexual Self-Concept and Sexual Self-Efficacy in Adolescents: A Possible Clue to Promoting Sexual Health? J. Sex Res. 2008, 45, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antičević, V.; Jokić-Begić, N.; Britvić, D. Sexual self-concept, sexual satisfaction, and attachment among single and coupled individuals. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 24, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potki, R.; Ziaei, T.; Faramarzi, M.; Moosazadeh, M.; Shahhosseini, Z. Bio-psycho-social factors affecting sexual self-concept: A systematic review. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5172–5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buzwell, S.; Rosenthal, D. Constructing a sexual self: Adolescents’ sexual self-perceptions and sexual risk-taking. J. Res. Adolesc. 1996, 6, 489–513. [Google Scholar]

- Aboujaoude, E. Virtually You: The Dangerous Powers of the E-Personality; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sumter, S.R.; Vandenbosch, L. Dating gone mobile: Demographic and personality-based correlates of using smartphone-based dating applications among emerging adults. New Media Soc. 2018, 21, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barrada, J.; Castro, Á. Tinder Users: Sociodemographic, Psychological, and Psychosexual Characteristics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochat, L.; Bianchi-Demicheli, F.; Aboujaoude, E.; Khazaal, Y. The psychology of “swiping”: A cluster analysis of the mobile dating app Tinder. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevi, B. The Dark Side of Tinder. J. Individ. Differ. 2019, 40, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, G.; Robilotta, A.; Fontanesi, L.; Sansone, A.; D’Antuono, L.; Limoncin, E.; Nimbi, F.; Simonelli, C.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Siracusano, A.; et al. Sexological Aspects Related to Tinder Use: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Sex. Med. Rev. 2020, 8, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.; Morahan-Martin, J.; Mathy, R.M.; Maheu, M. Toward an Increased Understanding of User Demographics in Online Sexual Activities. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2002, 28, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaughnessy, K.; Byers, E.S.; Walsh, L. Online Sexual Activity Experience of Heterosexual Students: Gender Similarities and Differences. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010, 40, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.J.; Finkelhor, D.; Wolak, J. The Exposure of Youth to Unwanted Sexual Material on the Internet: A National Survey of Risk, Impact, and Prevention. Youth Soc. 2003, 34, 330–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P.M. Adolescents’ Exposure to Sexually Explicit Internet Material and Sexual Preoccupancy: A Three-Wave Panel Study. Media Psychol. 2008, 11, 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koletić, G. Longitudinal associations between the use of sexually explicit material and adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors: A narrative review of studies. J. Adolesc. 2017, 57, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boies, S.C.; Cooper, A.; Osborne, C.S. Variations in Internet-Related Problems and Psychosocial Functioning in Online Sexual Activities: Implications for Social and Sexual Development of Young Adults. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2004, 7, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wéry, A.; Canale, N.; Bell, C.; Duvivier, B.; Billieux, J. Problematic online sexual activities in men: The role of self-esteem, loneliness, and social anxiety. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais-Lecours, S.; Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P.; Sabourin, S.; Godbout, N. Cyberpornography: Time Use, Perceived Addiction, Sexual Functioning, and Sexual Satisfaction. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Puertas, L.; Hernández, V.M.; Gutierrez-Puertas, V.; Granados-Gámez, G.; Rodríguez-García, M.C.; Aguilera-Manrique, G. Online sexual activities among university students: Relationship with sexual satisfaction. An. Psicol./Ann. Psychol. 2019, 36, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaughnessy, K.; Byers, E.S.; Clowater, S.L.; Kalinowski, A. Self-Appraisals of Arousal-Oriented Online Sexual Activities in University and Community Samples. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2013, 43, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, K.Y.A.; Green, A.S.; Smith, P. Demarginalizing the sexual self. J. Sex Res. 2001, 38, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumter, S.; Vandenbosch, L.; Ligtenberg, L. Love me Tinder: Untangling emerging adults’ motivations for using the dating application Tinder. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, E.S.; Shaughnessy, K. Attitudes toward online sexual activities. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2014, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wéry, A.; Billieux, J. Online sexual activities: An exploratory study of problematic and non-problematic usage patterns in a sample of men. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, N.; Mohseni, M.R. Are Online Sexual Activities and Sexting Good for Adults’ Sexual Well-Being? Results From a National Online Survey. Int. J. Sex. Health 2018, 30, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yue, C.; Zheng, L. Influence of online sexual activity (OSA) perceptions on OSA experiences among individuals in committed relationships: Perceived risk and perceived infidelity. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2019, 35, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.L. Revised Adult Attachment Scale. Behav. Ther. 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulhofer, A.; Buško, V.; Brouillard, P. The New Sexual Satisfaction Scale and its short form. In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures; Fisher, T.D., Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Davis, S.L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 530–532. [Google Scholar]

- JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.14.1). Computer Software. 2020. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grov, C.; Gillespie, B.J.; Royce, T.; Lever, J. Perceived Consequences of Casual Online Sexual Activities on Heterosexual Relationships: A U.S. Online Survey. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010, 40, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, M.W.; Månsson, S.-A.; Daneback, K. Prevalence, Severity, and Correlates of Problematic Sexual Internet Use in Swedish Men and Women. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2011, 41, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciocca, G.; Pelligrini, F.; Mollaioli, D.; Limoncin, E.; Sansone, A.; Colonnello, E.; Jannini, E.A.; Fontanesi, L. Hypersexual behavior and attachment styles in a non-clinical sample: The mediation role of depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jore, J.; Green, B.; Adams, K.; Carnes, P. Attachment Dysfunction and Relationship Preoccupation. Sex. Addict. Compuls. 2016, 23, 56–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanou, C.; McCabe, M.P. Adult Attachment and Sexual Functioning: A Review of Past Research. J. Sex. Med. 2012, 9, 2499–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.L.; Pioli, M.; Levitt, A.; Talley, A.E.; Micheas, L.; Collins, N.L. Attachment styles, sex motives, and sexual behavior. In Dynamics of Romantic Love: Attachment, Caregiving, and Sex; Mikulincer, M., Goodman, G.S., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 243–274. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, D.; Shaver, P.R.; Widaman, K.F.; Vernon, M.L.; Follette, W.C.; Beitz, K.; Davis, D.; Shaver, P.R.; Widaman, K.F.; Vernon, M.L.; et al. “I can’t get no satisfaction”: Insecure attachment, inhibited sexual communication, and sexual dissatisfaction. Pers. Relatsh. 2006, 13, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, K.M.; Dunkley, C.R.; Dang, S.S.; Gorzalka, B.B. Sexuality and romantic relationships: Investigating the relation between attachment style and sexual satisfaction. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2016, 31, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roșca, A.C.; Mateizer, A. Tulburările de atașament. In Abordarea Psihologică a Adopției și Asistenței Maternale. Polirom; Enea, V., Ed.; Editura Polirom: Iasi, Romania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, C.-I.; Roşca, A.C.; Mateizer, A. Job Crafting and Performance in Firefighters: The Role of Work Meaning and Work Engagement. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roșca, A.C.; Ciuraru, A.C. The Influence of Emotional Intelligence on Anxiety and Defense Mechanisms of People Diagnosed with Glaucoma. Rom. J. Exp. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 8, 415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Roșca, A.; Burtăverde, V.; Dan, C.-I.; Mateizer, A.; Petrancu, C.; Iriza, A.; Ene, C. The Dark Triad Traits of Firefighters and Risk-Taking at Work. The Mediating Role of Altruism, Honesty, and Courage. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roșca, A.C.; Mateizer, A.; Dan, C.-I.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands and Exhaustion in Firefighters: The Moderating Role of Work Meaning. A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | 1. Driven | 2. Competent | 3. Adventurous | 4. Unassured | 5. Naive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 40 | n = 73 | n = 45 | n = 39 | n = 47 | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Arousal | 35.8 (4.99) 2,4,5 | 29.5 (5.24) 1,3,5 | 37.93 (4.05) 2,4,5 | 28.17 (5.73) 1,3,5 | 23.3 (5.9) 1,2,3,4 |

| Exploration | 34.57 (5.71) 2,4,5 | 29.02 (5.55) 1,3 | 37.88 (5.14) 2,4,5 | 26.02 (7.31) 2,3 | 25.5 (7.83) 1,3 |

| Anxiety | 19.37 (4.99) 3,4,5 | 17.26 (4.07) 3,4,5 | 14.62 (3.57) 1,2,4,5 | 25.61 (6.82) 1,2,3 | 23.31 (4.5) 1,2,3 |

| Self-esteem | |||||

| Attractiveness | 21.45 (3.62) 2,3,4,5 | 24.06 (2.15) 1,4,5 | 25.42 (3.36) 1,4,5 | 17.8 (3.94) 1,2,3 | 18.9 (3.14) 1,2,3 |

| Behavior | 20.9 (1.75) 3,4,5 | 20.71 (1.77) 3,4,5 | 24.28 (0.99) 1,2,4,5 | 16.17 (3.04) 1,2,3,5 | 18.1 (1.8) 1,2,3,4 |

| Conduct | 16.85 (2.02) 3,4,5 | 16.41 (1.84) 3,4,5 | 18.15 (1.58) 1,2,4,5 | 11.87 (1.97) 1,2,3,5 | 13.2 (2.3) 1,2,3,4 |

| Self-efficacy | |||||

| Assertive | 26.42 (3.73) 2,3,4 | 20.3 (2.53) 1,4,5 | 20.93 (2.58) 1,4,5 | 12.59 (2.71) 1,2,3,5 | 17.6 (2.55) 2,3,4 |

| Resistive | 21.85 (5.78) 2,3,5 | 32.87 (4.18) 1,3,4 | 30 (5.11) 1,2,4 | 22.46 (6.63) 2,3,5 | 31.6 (3.9) 1,4 |

| Variables | 1. Driven | 2. Competent | 3. Adventurous | 4. Unassured | 5. Naïve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 40 | n = 73 | n = 45 | n = 39 | n = 47 | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Frequency of app use | |||||

| Tinder | 2.4 (1.9) | 1.76 (1.29) | 2.17 (1.76) | 2.02 (1.58) | 1.8 (1.32) |

| 4 (2.33) | 3.72 (2.05) | 3.86 (2.1) | 3.59 (2.04) | 3.31 (2.18) | |

| App Motives | |||||

| Love | 15.95 (5.46) | 15.82 (5.31) | 16.8 (5.66) | 16.17 (5.38) | 15.19 (5.53) |

| Casual sex | 11.22 (4.2) 2,4,5 | 8.74 (4.14) 1,3 | 11.86 (4.77) 2,4,5 | 8.28 (3.99) 1,3 | 8.21 (3.58) 1,3 |

| Ease of communication | 14.62 (5.27) | 14.05 (5.26) | 12.8 (4.23) | 14.48 (4.29) | 13.91 (4.47) |

| Self-worth | 14.17 (4.74) | 13.27 (5.51) | 12.91 (6.31) | 14.17 (5.03) | 12.29 (5.59) |

| Thrill of excitement | 6.12 (2.11) 5 | 5.26 (2.14) | 5.84 (2.4) 5 | 5.76 (1.85) | 4.59 (1.97) 1,3 |

| Trend | 8.17 (3.09) | 8.05 (3.09) | 8.2 (3.88) | 7.76 (2.55) | 6.95 (2.75) |

| No. of sex partners | 2.4 (2.93) 4,5 | 1.47 (1.41) 4,5 | 2.04 (2.54) 4,5 | 0.84 (0.74) 1,2,3 | 0.7 (0.6) 1,2,3 |

| OSAs | |||||

| Solitary | 10.72 (3.4) 2,4,5 | 7.52 (3.32) 1,3 | 11.31 (3.19) 2,4,5 | 7.56 (4.06) 1,3 | 8.08 (3.53) 1,3 |

| Partnered | 5.4 (2.63) 4 | 4.72 (2.08) | 5.75 (2.96) 4 | 3.87 (1.67) 1,3 | 4.17 (2.63) |

| Sexual satisfaction | |||||

| Ego-focused | 24.3 (3.5) 3,4,5 | 24.15 (4.39) 3,4,5 | 26.64 (4.08) 1,2,4,5 | 19.2 (5.76) 1,2,3 | 19.2 (6.6) 1,2,3 |

| Partner-focused | 21.3 (4.69) 5 | 23.5 (5.27) 4,5 | 24.44 (5.25) 4,5 | 18.76 (5.86) 2,3 | 17.8 (6.1) 1,2,3 |

| Attachment | |||||

| Anxiety | 3.06 (0.92) | 2.63 (1.09) 4 | 2.45 (0.98) 4,5 | 3.52 (1.08) 3 | 3.08 (1.06) 3 |

| Avoidance | 2.88 (0.54) | 2.73 (0.58) 4,5 | 2.78 (0.6) 4 | 3.22 (0.59) 2,3 | 3.03 (0.61) 2 |

| Style (%) | |||||

| Secure | 22.5 | 56.1 ** | 57.8 ** | 15.4 ** | 21.2 ** |

| Preoccupied | 30 | 15 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 23.4 |

| Fearful | 30 | 13.7 ** | 11.1 ** | 56.5 ** | 34 |

| Dismissive | 17.5 | 15 | 20 | 17.9 | 21.2 |

| Variables | 1. Driven | 2. Competent | 3. Adventurous | 4. Unassured | 5. Naïve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 40 | n = 73 | n = 45 | n = 39 | n = 47 | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Age | 27.22 (9.24) | 25.54 (9.26) | 27.02 (8.81) | 28.66 (10.71) | 27.25 (8.83) |

| (%) Gender M/F | 70/30 ** | 20.5/79.5 ** | 49/51 | 38.5/61.5 | 32/68 |

| (%) Relationship | |||||

| Single—inactive | 10 ** | 24.6 | 20 | 35.9 | 55.3 ** |

| Single—active | 17.5 | 16.4 | 15.5 | 7.7 | 6.4 |

| In a relationship | 72.5 | 58.9 | 64.5 | 56.4 | 38.3 ** |

| (%) Seeking online | 72.5 | 60.2 | 53.3 | 58.9 | 44.6 |

| (%) Cyber infidelity | 27.5 ** | 4.1 | 24.4 ** | 0 | 2.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mateizer, A.; Avram, E. Mobile Dating Applications and the Sexual Self: A Cluster Analysis of Users’ Characteristics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031535

Mateizer A, Avram E. Mobile Dating Applications and the Sexual Self: A Cluster Analysis of Users’ Characteristics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031535

Chicago/Turabian StyleMateizer, Alexandru, and Eugen Avram. 2022. "Mobile Dating Applications and the Sexual Self: A Cluster Analysis of Users’ Characteristics" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031535

APA StyleMateizer, A., & Avram, E. (2022). Mobile Dating Applications and the Sexual Self: A Cluster Analysis of Users’ Characteristics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031535