Gender-Oriented Mental Health Prevention: A Reappraisal

Abstract

1. Introduction

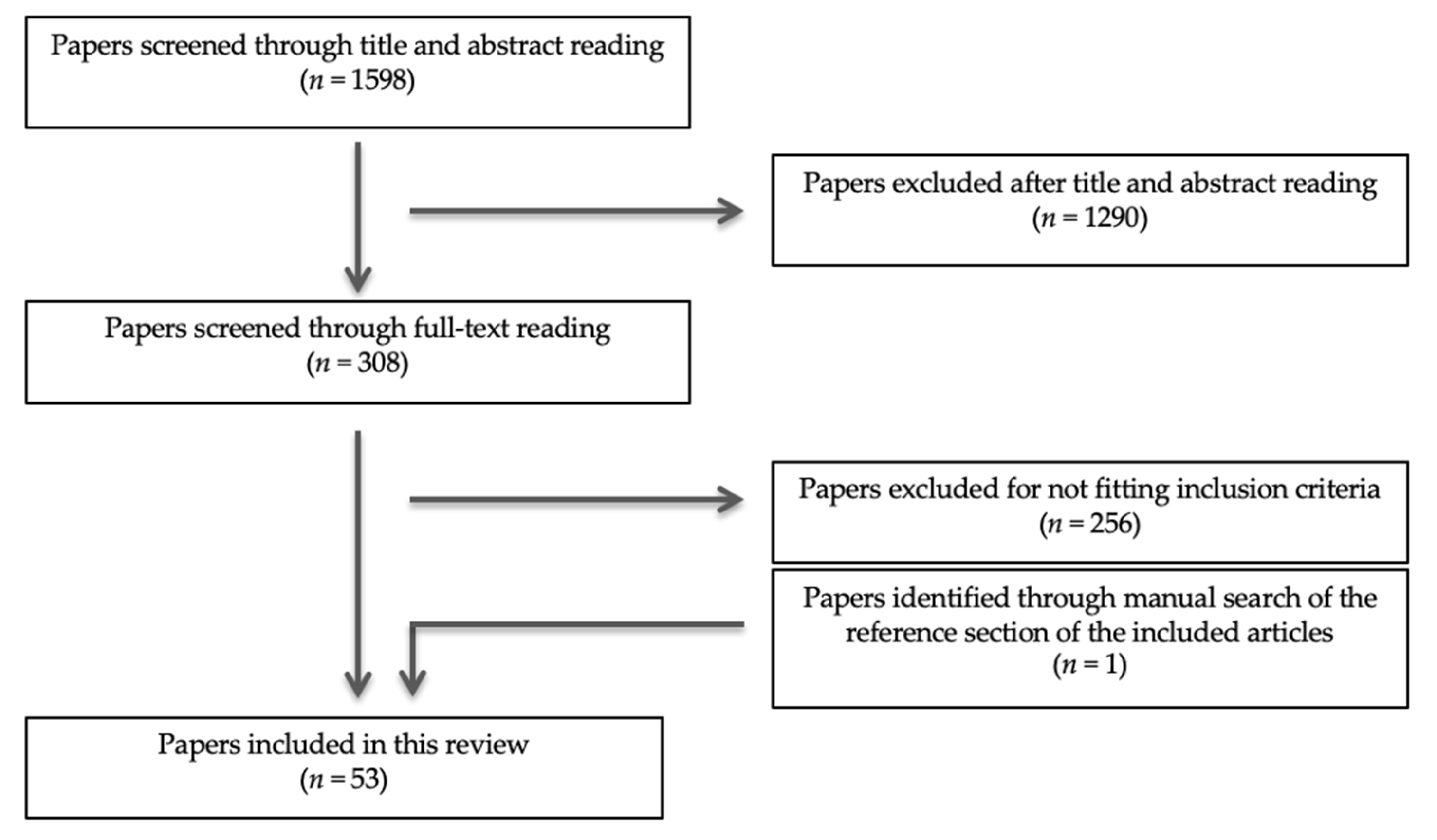

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Individual Factors

3.1.1. Childhood Adversities: Risk Factors and Long-Term Impact

3.1.2. At-Risk Children: Early Identification and Intervention

3.1.3. Gender-Oriented Prevention of Childhood Adversities

3.2. Familial Factors

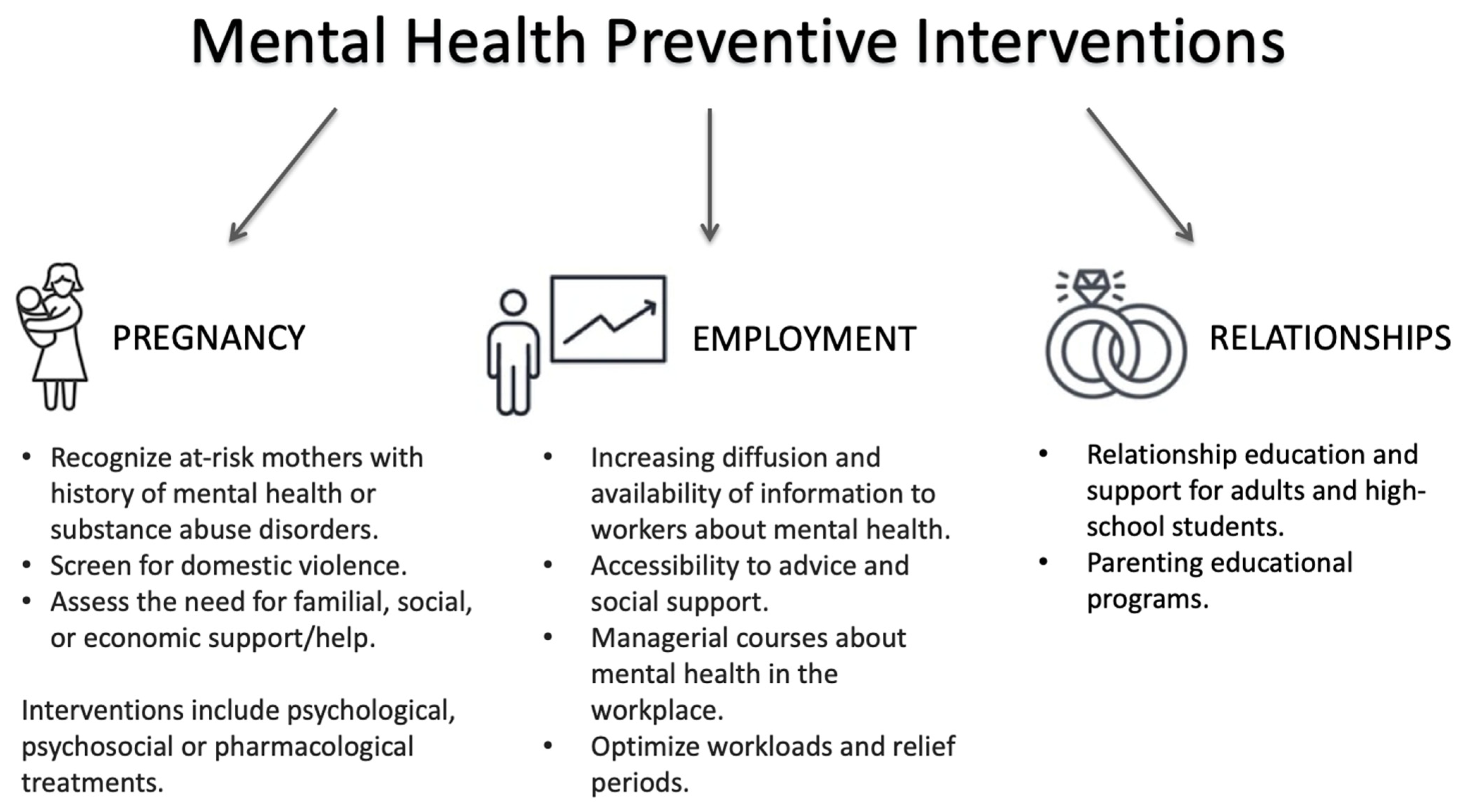

3.2.1. The Perinatal Period: A Sensitive Time in Life with Long-Lasting Effects

3.2.2. Detection of At-Risk Mothers

3.2.3. Availability of Effective Perinatal Interventions

3.2.4. Availability of an Organizational Framework for Interdisciplinary Interventions in Perinatal Health

3.3. Social Factors

3.3.1. Education

3.3.2. Employment

3.3.3. Relationships

3.4. Healthcare Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trivedi, J.K.; Tripathi, A.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Moussaoui, D. Preventive Psychiatry: Concept Appraisal and Future Directions. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2014, 60, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, T.S. The Effectiveness of Early Intervention: A Critical Review. J. Paediatr. Child Health 1992, 28, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Prevention of Mental Disorders. Effective Interventions and Policy Options; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Leavell, H.R.; Clark, E.G. Preventive Medicine for the Doctor in His Community: An Epidemiological Approach, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, J.; Scott, J. Concepts and Misconceptions Regarding Clinical Staging Models. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016, 41, E83–E84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C. Ultra-High-Risk Paradigm: Lessons Learnt and New Directions. Evid. Based. Ment. Health 2018, 21, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Khan, M.N.; Mahmood, W.; Patel, V.; Bhutta, Z.A. Interventions for Adolescent Mental Health: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2016, 49–60, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colizzi, M.; Lasalvia, A.; Ruggeri, M. Prevention and Early Intervention in Youth Mental Health: Is It Time for a Multidisciplinary and Trans-Diagnostic Model for Care? Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C. Early Intervention in Youth Mental Health: Progress and Future Directions. Evid.-Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Ebert, N.; Kurth, I.; Bacchus, C.; Overgaard, J. What Will Radiation Oncology Look like in 2050? A Look at a Changing Professional Landscape in Europe and Beyond. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietiläinen, E.; Roos, T.; Roos, O.; Rahkonen, S.; Heikkinen, K.; Seppä, H.; Ryynänen, J.P. Interactions of Smoking, Alcohol Use, Overweight and Physical Inactivity as Predictors of Cancer. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, cky214-053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosang, G.M.; Bhui, K. Gender Discrimination, Victimisation and Women’s Mental Health. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 682–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Martínez, T.; Robles, R. Preventing Transphobic Bullying and Promoting Inclusive Educational Environments: Literature Review and Implementing Recommendations. Arch. Med. Res. 2019, 50, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustard, J.F. Brain Development, Child Development–Adult Health and Well-Being and Paediatrics. Paediatr. Child Health 1999, 4, 519–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Maggi, S.; Irwin, L.J.; Siddiqi, A.; Hertzman, C. The Social Determinants of Early Child Development: An Overview. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2010, 46, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonagy, P.; Gergely, G.; Jurist, E.L.; Target, M. Attachment and Reflective Function: Their Role in Self-Organization. Affect Regul. Ment. Dev. Self 2018, 9, 23–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.E.; Levitt, P.; Nelson, C.A. How the Timing and Quality of Early Experiences Influence the Development of Brain Architecture. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.M.; Walker, S.P.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Andersen, C.T.; DiGirolamo, A.M.; Lu, C.; McCoy, D.C.; Fink, G.; Shawar, Y.R.; Shiffman, J.; et al. Early Childhood Development Coming of Age: Science through the Life Course. Lancet 2017, 389, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slopen, N.; Williams, D.R.; Fitzmaurice, G.M.; Gilman, S.E. Sex, Stressful Life Events, and Adult Onset Depression and Alcohol Dependence: Are Men and Women Equally Vulnerable? Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S.; Lankarani, M.M. Stressful Life Events and Risk of Depression 25 Years Later: Race and Gender Differences. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sege, R.D.; Amaya-Jackson, L.; Flaherty, E.G.; Idzerda, S.M.; Legano, L.A.; Leventhal, J.M.; Lukefahr, J.L.; Szilagyi, M.A.; Forkey, H.C.; Harmon, D.A.; et al. Clinical Considerations Related to the Behavioral Manifestations of Child Maltreatment. Pediatrics 2017, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, T.O.; MacMillan, H.L.; Boyle, M.; Taillieu, T.; Cheung, K.; Sareen, J. Child Abuse and Mental Disorders in Canada. CMAJ 2014, 186, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Li, Q.Y.; Liu, J.T.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Y.L.; Wang, C.Y. Childhood Trauma Associates with Clinical Features of Schizophrenia in a Sample of Chinese Inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 228, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, P.D.; Walker, J.L.; Rossouw, W.; Seedat, S.; Stein, D.J. Risk Indicators and Psychopathology in Traumatised Children and Adolescents with a History of Sexual Abuse. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 17, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devries, K.M.; Mak, J.Y.T.; Child, J.C.; Falder, G.; Bacchus, L.J.; Astbury, J.; Watts, C.H. Childhood Sexual Abuse and Suicidal Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e1331–e1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, A.M.; Ruzzi, V.; Patriciello, G.; Pellegrino, F.; Cascino, G.; Castellini, G.; Steardo, L.; Monteleone, P.; Maj, M. Parental Bonding, Childhood Maltreatment and Eating Disorder Psychopathology: An Investigation of Their Interactions. Eat. Weight Disord. 2020, 25, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshesha, L.Z.; Abrantes, A.M.; Anderson, B.J.; Blevins, C.E.; Caviness, C.M.; Stein, M.D. Marijuana Use Motives Mediate the Association between Experiences of Childhood Abuse and Marijuana Use Outcomes among Emerging Adults. Addict. Behav. 2019, 93, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensley, L.; Van Eenwyk, J.; Simmons, K.W. Childhood Family Violence History and Women’s Risk for Intimate Partner Violence and Poor Health. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2003, 25, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; Wade, M.; Plamondon, A.; Vaillancourt, K.; Jenkins, J.M.; Shouldice, M.; Benoit, D. Course of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms during the Transition to Parenthood for Female Adolescents with Histories of Victimization. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioux, S.; Wood, J.N.; Fakeye, O.; Luan, X.; Localio, R.; Rubin, D.M. Longitudinal Association of County-Level Economic Indicators and Child Maltreatment Incidents. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 2202–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, E.J.; Gelaye, B.; Bain, P.; Rondon, M.B.; Borba, C.P.C.; Henderson, D.C.; Williams, M.A. A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials of Interventions Designed to Decrease Child Abuse in High-Risk Families. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 65, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Davis, H.; McIntosh, E.; Jarrett, P.; Mockford, C.; Stewart-Brown, S. Role of Home Visiting in Improving Parenting and Health in Families at Risk of Abuse and Neglect: Results of a Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial and Economic Evaluation. Arch. Dis. Child. 2007, 92, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuMont, K.; Mitchell-Herzfeld, S.; Greene, R.; Lee, E.; Lowenfels, A.; Rodriguez, M.; Dorabawila, V. Healthy Families New York (HFNY) Randomized Trial: Effects on Early Child Abuse and Neglect. Child Abus. Negl. 2008, 32, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence. 2019; pp. 1–40. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/preventingACES.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- McNeil, H.J.; Holland, S.S. A Comparative Study of Public Health Nurse Teaching in Groups and in Home Visits. Am. J. Public Health 1972, 62, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- de Camps Meschino, D.; Philipp, D.; Israel, A.; Vigod, S. Maternal-Infant Mental Health: Postpartum Group Intervention. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, L.K.; Skavenski, S.; Kane, J.C.; Mayeya, J.; Dorsey, S.; Cohen, J.A.; Michalopoulos, L.T.M.; Imasiku, M.; Bolton, P.A. Effectiveness of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy among Trauma-Affected Children in Lusaka, Zambia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.A.; Mannarino, A.P.; Perel, J.M.; Staron, V. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Combined Trauma-Focused CBT and Sertraline for Childhood PTSD Symptoms. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 46, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellsberg, M.; Arango, D.J.; Morton, M.; Gennari, F.; Kiplesund, S.; Contreras, M.; Watts, C. Prevention of Violence against Women and Girls: What Does the Evidence Say? Lancet 2015, 385, 1555–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, H.L.; Jamieson, E.; Wathen, C.N.; Boyle, M.H.; Walsh, C.A.; Omura, J.; Walker, J.M.; Lodenquai, G. Development of a Policy-Relevant Child Maltreatment Research Strategy. Milbank Q. 2007, 85, 337–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagman, J.A.; Gray, R.H.; Campbell, J.C.; Thoma, M.; Ndyanabo, A.; Ssekasanvu, J.; Nalugoda, F.; Kagaayi, J.; Nakigozi, G.; Serwadda, D.; et al. Effectiveness of an Integrated Intimate Partner Violence and HIV Prevention Intervention in Rakai, Uganda: Analysis of an Intervention in an Existing Cluster Randomised Cohort. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2015, 3, e23–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.R.; Montgomery, S.B. India’s Distorted Sex Ratio: Dire Consequences for Girls. J. Christ. Nurs. 2016, 33, E7–E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, M.W.; Mc Cabe, J.E. Postpartum Depression: Current Status and Future Directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- das Carvalho, J.M.N.; Gaspar, M.F.R.F.; Cardoso, A.M.R. Challenges of Motherhood in the Voice of Primiparous Mothers: Initial Difficulties. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2017, 35, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deater-Deckard, K. Parenting Stress and Child Adjustment: Some Old Hypotheses and New Questions. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 1998, 5, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.M.; Molyneaux, E.; Dennis, C.L.; Rochat, T.; Stein, A.; Milgrom, J. Non-Psychotic Mental Disorders in the Perinatal Period. Lancet 2014, 384, 1775–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L.; Chung-Lee, L. Postpartum Depression Help-Seeking Barriers and Maternal Treatment Preferences: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Birth 2006, 33, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guille, C.; Newman, R.B. Treatment of Peripartum Mental Health Disorders: An Essential Element of Prenatal Care. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. 2018, 45, xv–xvi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, K.; Nissim, G.; Vaccaro, S.; Harris, J.L.; Lindhiem, O. Association between Maternal Depression and Maternal Sensitivity from Birth to 12 Months: A Meta-Analysis. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2018, 20, 578–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; Gaffan, E.A. Effects of Early Maternal Depression on Patterns of Infant-Mother Attachment: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2000, 41, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Pawlby, S.; Plant, D.T.; King, D.; Pariante, C.M.; Knapp, M. Perinatal Depression and Child Development: Exploring the Economic Consequences from a South London Cohort. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarcheski, A.; Mahon, N.E.; Yarcheski, T.J.; Hanks, M.M.; Cannella, B.L. A Meta-Analytic Study of Predictors of Maternal-Fetal Attachment. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J. Giving Kids a Fair Chance; Boston Review Books; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; 137p. [Google Scholar]

- Belay, S.; Astatkie, A.; Emmelin, M.; Hinderaker, S.G. Intimate Partner Violence and Maternal Depression during Pregnancy: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Parys, A.S.; Verhamme, A.; Temmerman, M.; Verstraelen, H. Intimate Partner Violence and Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Interventions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazmararian, J.A.; Petersen, R.; Spitz, A.M.; Goodwin, M.M.; Saltzman, L.E.; Marks, J. Violence and Reproductive Health: Current Knowledge and Future Research Directions. Matern. Child Health J. 2000, 4, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devries, K.M.; Kishor, S.; Johnson, H.; Stöckl, H.; Bacchus, L.J.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Watts, C. Intimate Partner Violence during Pregnancy: Analysis of Prevalence Data from 19 Countries. Reprod. Health Matters 2010, 18, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.E.; MacMillan, H.; Wathen, N. Intimate Partner Violence. Can. J. Psychiatry 2013, 58, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.C. Health Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence. Lancet 2002, 359, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.; Brody, D.; Hamilton, Z. Risk Factors for Domestic Violence during Pregnancy: A Meta-Analytic Review. Violence Vict. 2013, 28, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.; Levitt, C.; Wong, S.; Kaczorowski, J. Systematic Review of the Literature on Postpartum Care: Effectiveness of Postpartum Support to Improve Maternal Parenting, Mental Health, Quality of Life, and Physical Health. Birth 2006, 33, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarestrup, A.K.; Skovgaard Væver, M.; Petersen, J.; Røhder, K.; Schiøtz, M. An Early Intervention to Promote Maternal Sensitivity in the Perinatal Period for Women with Psychosocial Vulnerabilities: Study Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.R.; Records, K.; Low, L.K.; Alhusen, J.L.; Kenner, C.; Bloch, J.R.; Premji, S.S.; Hannan, J.; Anderson, C.M.; Yeo, S.; et al. Promotion of Maternal–Infant Mental Health and Trauma-Informed Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JOGNN-J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2020, 49, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Schmeid, V.; Lupton, S.J.; Austin, M.P.; Matthey, S.M.; Kemp, L.; Meade, T.; Yeo, A.E. Measuring Perinatal Mental Health Risk. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2012, 15, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhouse, H.; Gartland, D.; Mensah, F.; Brown, S.J. Maternal Depression from Early Pregnancy to 4 Years Postpartum in a Prospective Pregnancy Cohort Study: Implications for Primary Health Care. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 122, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josefsson, A.; Sydsjö, G. A Follow-up Study of Postpartum Depressed Women: Recurrent Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Child Behavior after Four Years. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2007, 10, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukatu, N.; Clare, C.A.; Brulja, M. Postpartum Depression Screening Tools: A Review. Psychosomatics 2018, 59, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöckl, H.; Hertlein, L.; Himsl, I.; Ditsch, N.; Blume, C.; Hasbargen, U.; Friese, K.; Stöckl, D. Acceptance of Routine or Case-Based Inquiry for Intimate Partner Violence: A Mixed Method Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, N.A.; Lewis-O’connor, A. Screening for Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy. Rev Obs. Gynecol. 2013, 6, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renker, P.R.; Tonkin, P. Women’s Views of Prenatal Violence Screening: Acceptability and Confidentiality Issues. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisner, K.L.; Wheeler, S.B. Prevention of Recurrent Postpartum Major Depression. Psychiatr. Serv. 1994, 45, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, K.L.; Perel, J.M.; Peindl, K.S. Prevention of Recurrent Postpartum Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2001, 3, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichel, D.A.; Cohen, L.S.; Robertson, L.M.; Ruttenberg, A.; Rosenbaum, J.F. Prophylactic Estrogen in Recurrent Postpartum Affective Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 1995, 38, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, K. Postnatal Depression and Prophylactic Progesterone. Br. J. Fam. Plann. 1994, 19, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, K. Progesterone or Progestogens? Br. Med. J. 1976, 2, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lawrie, T.A.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; De Jager, M.; Berk, M.; Paiker, J.; Viljoen, E. A Double-Blind Randomised Placebo Controlled Trial of Postnatal Norethisterone Enanthate: The Effect on Postnatal Depression and Serum Hormones. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1998, 105, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, B.; Oretti, R.; Lazarus, J.; Parkes, A.; John, R.; Richards, C.; Newcombe, R.; Hall, R. Randomised Trial of Thyroxine to Prevent Postnatal Depression in Thyroid-Antibody-Positive Women. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, B.; Fung, H.; Johns, S.; Kologlu, M.; Bhatti, R.; McGregor, A.M.; Richards, C.J.; Hall, R. Transient Post-Partum Thyroid Dysfunction and Postnatal Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 1989, 17, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente, A.M.; Jensen, C.L.; Voigt, R.G.; Fraley, J.K.; Berretta, M.C.; Heird, W.C. Effect of Maternal Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation on Postpartum Depression and Information Processing. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 188, 1348–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbeln, J.R. Fish Consumption and Major Depression. Lancet 1998, 351, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison-Hohner, J.; Coste, S.; Dorato, V.; Curet, L.B.; McCarron, D.; Hatton, D. Prenatal Calcium Supplementation and Postpartum Depression: An Ancillary Study to a Randomized Trial of Calcium for Prevention of Preeclampsia. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2001, 3, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thys-Jacobs, S.; Alvir, M.A.J. Calcium-Regulating Hormones across the Menstrual Cycle: Evidence of a Secondary Hyperparathyroidism in Women with PMS. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995, 80, 2227–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battle, C.L.; Salisbury, A.L.; Schofield, C.A.; Ortiz-Hernandez, S. Perinatal Antidepressant Use: Understanding Women’s Preferences and Concerns. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2013, 19, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnick, C.; Johnson, S.L.; Miller, I.W.; Pearlstein, T.; Howard, M. Postpartum Depression in Women Receiving Public Assistance: Pilot Study of an Interpersonal-Therapy-Oriented Group Intervention. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, L.L. Prevention of Postpartum Depression in a High Risk Sample; Department of Psychology, University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Saisto, T.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Nurmi, J.E. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Intervention in Fear of Childbirth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 98, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabrol, H.; Teissedre, F.; Saint-Jean, M.; Teisseyre, N.; Rogé, B.; Mullet, E. Prevention and Treatment of Post-Partum Depression: A Controlled Randomized Study on Women at Risk. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavender, T.; Walkinshaw, S.A. Can Midwives Reduce Postpartum Psychological Morbidity? A Randomized Trial. Birth 1998, 25, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, R.; Lumley, J.; Donohue, L.; Potter, A.; Waldenström, U. Randomised Controlled Trial of Midwife Led Debriefing to Reduce Maternal Depression after Operative Childbirth. BMJ 2000, 321, 1043–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priest, S.R.; Henderson, J.; Evans, S.F.; Hagan, R. Stress Debriefing after Childbirth: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Med. J. Aust. 2003, 178, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.E.; Gordon, K.K. Social Factors in Prevention of Postpartum Emotional Problems. Obs. Gynecol. 1960, 15, 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, S.A.; Leverton, T.J.; Sanjack, M.; Turner, H.; Cowmeadow, P.; Hopkins, J.; Bushnell, D. Promoting Mental Health after Childbirth: A Controlled Trial of Primary Prevention of Postnatal Depression. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 39, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamp, G.E.; Williams, A.S.; Crowther, C.A. Evaluation of Antenatal and Postnatal Support to Overcome Postnatal Depression: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Birth 1995, 22, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugha, T.S.; Wheatley, S.; Taub, N.A.; Culverwell, A.; Friedman, T.; Kirwan, P.; Jones, D.R.; Shapiro, D.A. Pragmatic Randomized Trial of Antenatal Intervention to Prevent Post-Natal Depression by Reducing Psychosocial Risk Factors. Psychol. Med. 2000, 30, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buist, A.; Westley, D.; Hill, C. Antenatal Prevention of Postnatal Depression. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 1999, 1, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolman, W.L.; Chalmers, B.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Nikodem, V.C. Postpartum Depression and Companionship in the Clinical Birth Environment: A Randomized, Controlled Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993, 168, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikodem, V.C.; Nolte, A.G.; Wolman, W.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Hofmeyr, G.J. Companionship by a Lay Labour Supporter to Modify the Clinical Birth Environment: Long-Term Effects on Mother and Child. Curationis 1998, 21, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, N.P.; Walton, D.; McAdam, E.; Derman, J.; Gallitero, G.; Garrett, L. Effects of Providing Hospital-Based Doulas in Health Maintenance Organization Hospitals. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 93, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodnett, E.D.; Lowe, N.K.; Hannah, M.E.; Willan, A.R.; Stevens, B.; Weston, J.A.; Ohlsson, A.; Gafni, A.; Muir, H.A.; Myhr, T.L.; et al. Effectiveness of Nurses as Providers of Birth Labor Support in North American Hospitals: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 288, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, K.L.; Fraser, J.A.; Dadds, M.R.; Morris, J. Promoting Secure Attachment, Maternal Mood and Child Health in a Vulnerable Population: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2000, 36, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, K.L.; Fraser, J.A.; Dadds, M.R.; Morris, J. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Nurse Home Visiting to Vulnerable Families with Newborns. J. Paediatr. Child Health 1999, 35, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, C.J.; Spiby, H.; Stewart, P.; Walters, S.; Morgan, A. Costs and Effectiveness of Community Postnatal Support Workers: Randomised Controlled Trial. Br. Med. J. 2000, 321, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.; Glazener, C.; Murray, G.D.; Taylor, G.S. A Two-Centred Pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trial of Two Interventions of Postnatal Support. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2002, 109, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, J.A.; Mendelson, T.; Tandon, S.D.; Perry, D.F. A Systematic Review of Home-Based Interventions to Prevent and Treat Postpartum Depression. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2009, 12, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, N.; Reid, M.; Cheyne, H.; Holmes, A.; Mcginley, M.; Turnbull, D.; Smith, L.N. Impact of Midwife-Managed Care in the Postnatal Period: An Exploration of Psychosocial Outcomes. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 1997, 15, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldenström, U.; Brown, S.; McLachlan, H.; Forster, D.; Brennecke, S. Does Team Midwife Care Increase Satisfaction with Antenatal, Intrapartum, and Postpartum Care? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Birth 2000, 27, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, M.N.; Siddle, K.; Warwick, C. Can We Prevent Postnatal Depression? A Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess the Effect of Continuity of Midwifery Care on Rates of Postnatal Depression in High-Risk Women. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2003, 13, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Linnane, J.; Roberts, J.; Starrenburg, S.; Hinson, J.; Dibley, L. IDentify, Educate and Alert (IDEA) Trial: An Intervention to Reduce Postnatal Depression. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2003, 110, 842–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwint, J.R.; Wilson, M.H.; Duggan, A.K.; Mellits, E.D.; Baumgardner, R.A.; DeAngelis, C. Do Postpartum Nursery Visits by the Primary Care Provider Make a Difference? Pediatrics 1991, 88, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, J.; Lumley, J.; Chondros, P.; Young, D. Does an Early Postnatal Check-up Improve Maternal Health: Results from a Randomised Trial in Australian General Practice. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1998, 105, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, T.; Nagata, S.; Hasegawa, M.; Nomura, J.; Kumar, R. Effectiveness of Antenatal Education about Postnatal Depression: A Comparison of Two Groups of Japanese Mothers. J. Ment. Health 1998, 7, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heh, S.S.; Fu, Y.Y. Effectiveness of Informational Support in Reducing the Severity of Postnatal Depression in Taiwan. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 42, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B.A.; Muller, R.; Bradley, B.S. Perinatal Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Antenatal Education Intervention for Primiparas. Birth 2001, 28, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorant, V.; Deliège, D.; Eaton, W.; Robert, A.; Philippot, P.; Ansseau, M. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Depression: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 157, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermakova, P.; Pikhart, H.; Kubinova, R.; Bobak, M. Education as Inefficient Resource against Depressive Symptoms in the Czech Republic: Cross-Sectional Analysis of the HAPIEE Study. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Lacruz, M.; Gil-Lacruz, A.I.; Gracia-Pérez, M.L. Health-Related Quality of Life in Young People: The Importance of Education. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, C.E.; Mirowsky, J. Sex Differences in the Effect of Education on Depression: Resource Multiplication or Resource Substitution? Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 1400–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, C.E.; Mirowsky, J. The Interaction of Personal and Parental Education on Health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaan, B. The Interaction of Family Background and Personal Education on Depressive Symptoms in Later Life. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 102, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigaiani, Y.; Zoccante, L.; Zocca, A.; Arzenton, A.; Menegolli, M.; Fadel, S.; Ruggeri, M.; Colizzi, M. Adolescent Lifestyle Behaviors, Coping Strategies and Subjective Wellbeing during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Student Survey. Healthcare 2020, 8, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, E.A.; Connelly, C.D.; Thomas-Jones, D.; Eggert, L.L. School Difficulties and Co-Occurring Health Risk Factors: Substance Use, Aggression, Depression, and Suicidal Behaviors. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2013, 26, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligier, F.; Giguère, C.E.; Notredame, C.E.; Lesage, A.; Renaud, J.; Séguin, M. Are School Difficulties an Early Sign for Mental Disorder Diagnosis and Suicide Prevention? A Comparative Study of Individuals Who Died by Suicide and Control Group. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, C.; Godderis, R.; Hua, J.; McEwan, K.; Wong, W. Preventing and Treating Anxiety Disorders in Children and Youth. A Research Report Prepared for the British Columbia Ministry of Children and Family Development. 2004. Volume 1. Available online: https://childhealthpolicy.ca/wp-content/themes/chpc/pdf/RR-5-04-full-report.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Eurostat. Employment-Annual Statistics. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/11156668/3-30072020-AP-EN.pdf/1b69a5ae-35d2-0460-f76f-12ce7f6c34be (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Paul, K.I.; Moser, K. Unemployment Impairs Mental Health: Meta-Analyses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahoda, M. Employment and Unemployment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist, S.; Burström, B.; Backhans, M.C. Increasing Health Inequalities between Women in and out of Work-The Impact of Recession or Policy Change? A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study in Stockholm County, 2006 and 2010. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydsten, A.; Hammarström, A.; San Sebastian, M. Health Inequalities between Employed and Unemployed in Northern Sweden: A Decomposition Analysis of Social Determinants for Mental Health. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarström, A.; Gustafsson, P.E.; Janlert, U.; Strandh, M.; Virtanen, P. It’s No Surprise! Men Are Not Hit More than Women by the Health Consequences of Unemployment in the Northern Swedish Cohort. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novo, M.; Hammarström, A.; Janlert, U. Do High Levels of Unemployment Influence the Health of Those Who Are Not Unemployed? A Gendered Comparison of Young Men and Women during Boom and Recession. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burström, B.; Nylén, L.; Barr, B.; Clayton, S.; Holland, P.; Whitehead, M. Delayed and Differential Effects of the Economic Crisis in Sweden in the 1990s on Health-Related Exclusion from the Labour Market: A Health Equity Assessment. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2431–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetzler, A.; Melén, D.; Bjerstedt, D. Sjuk-Sverige: Försäkringskassan, Rehabilitering Och Utslagning Från Arbetsmarknaden. Brutus Östlings Bokförlag Symposion. 2005. Available online: https://portal.research.lu.se/en/publications/sjuk-sverige-f%C3%B6rs%C3%A4kringskassan-rehabilitering-och-utslagningen-fr (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Bayer, P.B. Mutable Characteristics and the Definition of Discrimination Under Title VII. 20 U.C. Davis L. Rev 1986, 20, 769–882. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe, E.A.; Richman, L.S. Perceived Discrimination and Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.; Mickelson, K.; Williams, D. The Prevalence, Distribution, and Mental Health Correlates of Perceived Discrimination in the United States. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1999, 40, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.K.; Sim, J.; Kim, Y.; Yun, B.Y.; Yoon, J.H. Multidimensional Gender Discrimination in Workplace and Depressive Symptoms. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Keyes, K.M. Responses to Discrimination and Psychiatric Disorders among Black, Hispanic, Female, and Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UE (EIGE). Gender Equality Index 2015. Measuring Gender Equality in the European Union 2005-2012; EIGE: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2015; ISBN 9789292186913. [Google Scholar]

- Trades Union Congress Still Just a Bit of Banter? Sexual Harassment in the Workplace. 2016. Available online: https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/SexualHarassmentreport2016.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Moss-Racusin, C.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Brescoll, V.L.; Graham, M.J.; Handelsman, J. Science Faculty’s Subtle Gender Biases Favor Male Students. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16474–16479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, K.W.; Hankivsky, O.; Bates, L.M. Gender and Health: Relational, Intersectional, and Biosocial Approaches. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1661–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shippee, T.P.; Wilkinson, L.R.; Schafer, M.H.; Shippee, N.D. Long-Term Effects of Age Discrimination on Mental Health: The Role of Perceived Financial Strain. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2019, 74, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification. 2008. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/1292.0.55.0052008?OpenDocument (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Tynan, R.J.; Considine, R.; Rich, J.L.; Skehan, J.; Wiggers, J.; Lewin, T.J.; James, C.; Inder, K.; Baker, A.L.; Kay-Lambkin, F.; et al. Help-Seeking for Mental Health Problems by Employees in the Australian Mining Industry. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidler, Z.E.; Dawes, A.J.; Rice, S.M.; Oliffe, J.L.; Dhillon, H.M. The Role of Masculinity in Men’s Help-Seeking for Depression: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 49, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addis, M.E.; Mahalik, J.R. Men, Masculinity, and the Contexts of Help Seeking. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åhs, A.; Burell, G.; Westerling, R. Care or Not Care-That Is the Question: Predictors of Healthcare Utilisation in Relation to Employment Status. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 19, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battams, S.; Roche, A.M.; Fischer, J.A.; Lee, N.K.; Cameron, J.; Kostadinov, V. Workplace Risk Factors for Anxiety and Depression in Male-Dominated Industries: A Systematic Review. Heal. Psychol. Behav. Med. 2014, 2, 983–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.; White, A.; Gough, B.; Robinson, M.; Seims, A.; Raine, G.; Hanna, E. Promoting Mental Health and Wellbeing with Men and Boys: What Works? In Project Report; Centre for Men’s Health, Leeds Beckett University: Leeds, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-907240-41-6. Available online: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/1508/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Lee, N.K.; Roche, A.; Duraisingam, V.; Fischer, J.A.; Cameron, J. Effective Interventions for Mental Health in Male-Dominated Workplaces. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2014, 19, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, H.; Bebbington, P.; Brugha, T.; Jenkins, R.; McManus, S.; Stansfeld, S. Job Insecurity, Socio-Economic Circumstances and Depression. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne, A.D.; Keegel, T.; Louie, A.M.; Ostry, A.; Landsbergis, P.A. A Systematic Review of the Job-Stress Intervention Evaluation Literature, 1990–2005. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2007, 13, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, C.L.; Bottorff, J.L.; Jones-Bricker, M.; Oliffe, J.L.; DeLeenheer, D.; Medhurst, K. Men’s Mental Health Promotion Interventions: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Mens Health 2017, 11, 1823–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilderbeck, A.C.; Farias, M.; Brazil, I.A.; Jakobowitz, S.; Wikholm, C. Participation in a 10-Week Course of Yoga Improves Behavioural Control and Decreases Psychological Distress in a Prison Population. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirokawa, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Tsuchiya, M.; Kawakami, N. Effects of a Stress Management Program for Hospital Staffs on Their Coping Strategies and Interpersonal Behaviors. Ind. Health 2012, 50, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarman, L.; Martin, A.; Venn, A.; Otahal, P.; Sanderson, K. Does Workplace Health Promotion Contribute to Job Stress Reduction? Three-Year Findings from Partnering Healthy@Work. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Kaneyoshi, A.; Yokota, A.; Kawakami, N. Effects of a Worker Participatory Program for Improving Work Environments on Job Stressors and Mental Health among Workers: A Controlled Trial. J. Occup. Health 2008, 50, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K. Has the Future of Marriage Arrived? A Contemporary Examination of Gender, Marriage, and Psychological Well-Being. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003, 44, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, J. Structures and Processes of Social Support. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1988, 14, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Butterfield, R. Social Control in Marital Relationships: Effect of One’s Partner on Health Behaviors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gove, W.R.; Style, C.B.; Hughes, M. The Effect of Marriage on the Well-Being of Adults. J. Fam. Issues 1990, 11, 4–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohschein, L.; McDonough, P.; Monette, G.; Shao, Q. Marital Transitions and Mental Health: Are There Gender Differences in the Short-Term Effects of Marital Status Change? Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.W. Revisiting the Relationships among Gender, Marital Status, and Mental Health. Am. J. Sociol. 2002, 107, 1065–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.M.; Subaiya, L.; Kahn, J.R. The Gender Gap in the Economic Well-Being of Nonresident Fathers and Custodial Mothers. Demography 1999, 36, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ooms, T.; Bouchet, S.; Parke, M. Beyond Marriage Licenses: Efforts to Strengthen Marriage and Two-Parent Families. Cent. Law Soc. Policy Washington DC 2004, 53, 440–447. [Google Scholar]

- Hauge, L.J.; Stene-Larsen, K.; Grimholt, T.K.; Øien-ØDegaard, C.; Reneflot, A. Use of Primary Health Care Services Prior to Suicide in the Norwegian Population 2006-2015. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Patel, V. The Global Dissemination of Psychological Treatments: A Road Map for Research and Practice. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Green, J.G.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alhamzawi, A.O.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.; et al. Childhood Adversities and Adult Psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, M.J. Depression Is the Leading Cause of Disability around the World. JAMA 2017, 317, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Bairey Merz, N.; Barnes, P.J.; Brinton, R.D.; Carrero, J.J.; DeMeo, D.L.; De Vries, G.J.; Epperson, C.N.; Govindan, R.; Klein, S.L.; et al. Sex and Gender: Modifiers of Health, Disease, and Medicine. Lancet 2020, 396, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rask, K.; Åstedt-Kurki, P.; Paavilainen, E.; Laippala, P. Adolescent Subjective Well-Being and Family Dynamics. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2003, 17, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Serna, J.; Ronda-Pérez, E.; Artazcoz, L.; Moen, B.E.; Benavides, F.G. Gender Inequalities in Occupational Health Related to the Unequal Distribution of Working and Employment Conditions: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Dunsford, M.; Skagerberg, E.; Holt, V.; Carmichael, P.; Colizzi, M. Psychological Support, Puberty Suppression, and Psychosocial Functioning in Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 2206–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colizzi, M.; Costa, R.; Pace, V.; Todarello, O. Hormonal Treatment Reduces Psychobiological Distress in Gender Identity Disorder, Independently of the Attachment Style. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 3049–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colizzi, M.; Costa, R.; Todarello, O. Transsexual Patients’ Psychiatric Comorbidity and Positive Effect of Cross-Sex Hormonal Treatment on Mental Health: Results from a Longitudinal Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 39, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tool | No. of Items | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Childhood abuse | ||

| Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children/Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children (TSCC/TSCYC) | 20 | The clinical scales include PTS-Intrusion, PTS-Avoidance, PTS-Arousal, Sexual Concerns, Anxiety, Depression, Dissociation, and Anger/Aggression. |

| UCLA PTSD Reaction Index (UCLA PTSD-RI) | 12 | It includes parent-report and self-report versions. It asks individuals to identify the current most impairing event and asks questions about the child’s reactions during or directly after exposure to that event. Finally, it assesses PTSD symptom frequency on a 5-point Likert scale within the past month. |

| Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS) | 26 | Respondents indicate how often they experienced each symptom in the past month on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (5 or more times a week). |

| Perinatal mental health problems | ||

| Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA) | 35 | It identifies antenatal psychosocial risk factors that would lead to poor postnatal psychosocial outcomes. Questions are scored using a three-point tick-box system of ‘low’, ‘some’ and ‘high’. |

| Antenatal Risk Questionnaire (ANRQ) | 12 | It assesses the following psychosocial risk domains: emotional support from subject’smother in childhood, past history of depressed mood or mental illness and treatment received, perceived level of support available following the birth of the baby, partner emotional support, life stresses in the previous 12 months, personality style (anxious or perfectionistic traits) and history of abuse (emotional, physical and sexual). |

| Australian Routine Psychosocial Assessment (ARPA) | 12 | The tool assesses support, stressors, personality, mental health, childhood abuse, family violence and current mood. |

| Camberwell Assessment of Need—Mothers (CAN-M) | 26 | It covers the domains of accommodation, food, looking after the home, self-care, daytime activities, general physical health, pregnancy care, sleep, psychotic symptoms, psychological distress, information, safety to self, safety to child and others, substance misuse, company, intimate relationships, sexual health, violence and abuse, practical demands of childcare, emotional demands of childcare, basic education, telephone, transport, budgeting, benefits, language, culture and religion. Domains are assessed on a five-point Likert scale of importance (ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘essential’). |

| Contextual Assessment of Maternity Experience (CAME) | 3 | It explores recent life adversity or stressors, the quality of social support and key relationships including partner relationship, and maternal feelings towards pregnancy, motherhood and the baby. |

| Pregnancy risk questionnaire (PRQ) | 18 | It assesses mother’s attitude to her pregnancy, mother’s experience of parenting in childhood, history of physical or sexual abuse, history of depression, the impact of depression on psychosocial function, whether treatment was sought or recommended, presence of emotional support from partner and mother, presence of other supports, presence of stressors during pregnancy, trait anxiety, obsessional traits and self-esteem. A five-point Likert scale is used, from 1 ‘not at all’ to 5 ‘very much’. |

| Postnatal depression | ||

| Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) | 10 | It is the most widely tested screening tool for postnatal depression, although its sensitivity varies from 22% to 96%. Possible scores range from 0 to 30, with 11 and 13 being the most commonly used cut-offs to detect “probable” depression. It limits questions to feelings of sadness or anxiety, without screening for physical symptoms. Its reference period is narrow since it allows patients to report symptoms felt during the week before the assessment. |

| Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS) | 35 | It assesses Sleeping/Eating Disturbances, Anxiety/Insecurity, Emotional Lability, Cognitive Impairment, Loss of Self, Guilt/Shame, and Contemplating Harming Oneself. On completing the scale, a mother is asked to select a label from (1) to (5) to reflect her degree of disagreement or agreement, where (1) means strongly disagree and (5) means strongly agree. |

| Beck’s Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) | 21 | It measures the severity of depression with four response options ranging from 0 to 3 for each item, with a total maximum score for all items being 63. A score of 0–13 is considered minimal, 14–19 mild, 20–28 moderate, and 29–63 is considered severe depression. |

| General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12) | 12 | It has four response options and an overall rating from 0 to 12 used to assess mental health and psychological adjustment. |

| Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) | 20 | It is a Likert-format screening tool that asks respondents how often they experienced a particular symptom in the past week, where 0 represents “rarely or none of the time” and 3 represents “most or all of the time” (range 0–60). |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) | 9 | It assesses the experiencing of depressive symptoms over the last 14 days. Scores on the PHQ-9 range from 0 to 27 and are calculated by assigning scores of 0, 1, 2 or 3 to response categories of ‘not at all’, ‘several days’, ‘more than half the days’ or ‘nearly every day’, respectively and then summing up the scores. |

| Intimate partner violence | ||

| RADAR | 5 | It is an acronym-mnemonic that helps summarize key action steps that physicians should take in recognizing and treating patients affected by IPV. The tool includes (1) Routinely screening adult patients, (2) Asking direct questions, (3) Documenting your findings, (4) Assessing patient safety, and (5) Reviewing options and referrals. |

| HIITS | 5 | The tool asks a patient the following questions: How often does your partner physically hurt you, insult or talk down to you, threaten you with harm, and scream or curse at you? Each category is graded on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (frequently) and a sum of all the categories is generated. A total score of 10 or above is suggestive of IPV. |

| Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS) | 5 | It involves the following open-ended questions: 1. Have you ever been emotionally or physically abused by your partner or someone important to you? 2. Since I saw you last have you been hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise physically hurt by someone? If YES, by whom? Number of times? Nature of injury? 3. Since you have been pregnant, have you been hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise physically hurt by someone? If YES, by whom? Number of times? Nature of injury? 4. Within the past year has anyone made you do something sexual that you did not want to do? If YES, then who? 5. Are you afraid of your partner or anyone else? |

| Intervention | Author(s) | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Biological | ||

| Prophylactic medication in the postpartum with Nortriptyline | Wisner et al., 1994 Wisner et al., 2001 | In one study, prophylactic Nortryptiline appeared to be effective in reducing postpartum depression relapse at 12 weeks postpartum (Wisner et al., 1994), whereas the other study found no difference in depressive levels at 20 weeks postpartum between women taking the antidepressant versus controls (Wisner et al., 2001). |

| Prophylactic effect of estrogen and progesterone therapy in preventing postpartum depression | Sichel et al., 1995 Dalton et al., 1994 Dalton et al., 1976 Lawrie et al., 1998 | Results were promising for prophylactic estrogen therapy (Sichel et al., 1995) but highly inconsistent for prophylactic progesterone therapy, with two small studies showing a reduction in the postpartum depression recurrence rate (Dalton et al., 1994–1976) and another larger trial showing an increased risk of developing depressing symptoms in women taking part in progesterone therapy compared to controls (Lawrie et al., 1998). |

| Thyroid antibodies in the postpartum | Harris et al., 2002 | A small trial failed to show an effect in the occurrence of depression in thyroid-antibody-positive women taking thyroxine postpartum compared to thyroid-antibody-positive women taking a placebo. |

| Docosahexanoic Acid (DHA) in postpartum | Llorente et al., 2003 | A small trial did not show a significant effect on postpartum depression rates. |

| Calcium supplementation | Harrison-Hohner et al., 2001 | Promising effect in preventing postpartum depression in a small trial, since calcium metabolism is influenced by fluctuations in gonadal hormones that are exacerbated in the postpartum period. |

| Psychological | ||

| Interpersonal therapy | Zlotnick et al., 2001 Gorman et al., 2001 | Interpersonal therapy appeared to be effective in preventing depression compared to controls at four weeks postpartum, but this prophylactic effect was not maintained at 24 weeks postpartum (Gorman et al., 2001). |

| Cognitive-behavioral therapy | Chabrol et al., 2002 | One study showed that CBT is efficacious and well-accepted for post-partum depression |

| Midwife-led psychological debriefing | Lavender et al., 1998 Small et al., 2000 Priest et al., 2003 Gordon and Gordon, 1960 Elliott et al., 2000 | Midwife-led debriefing appeared to be effective in lowering anxiety and depression scores in the postnatal period (Lavender et al., 1998). In one study, women in the psychological debriefing group presented with less depressive symptoms at 3 weeks postpartum compared to controls (Small et al., 2000), in another study women in the experimental group showed higher levels of depressive symptoms at 24 weeks postpartum compared to controls (Priest et al., 2003), and in the remaining two studies no difference in depressive levels was found between treated woman and controls (Gordon and Gordon, 1960; Elliott et al., 2000). |

| Psychosocial | ||

| Antenatal classes | Stamp et al., 1995 Brugha et al., 2000 Buist et al., 1999 | Effective in preventing postpartum depression only in one trial (Stamp et al., 1995), whereas in two studies no differences were found in depressive levels between experimental and control groups (Brugha et al., 2000; Buist et al., 1999). |

| Intrapartum support | Wolman et al., 1993 Nikodem et al., 1998 Gordon et al., 1999 Hodnett et al., 2002 | Effective in preventing postpartum depression at 6 weeks but not at 1 year postpartum (Wolman et al., 1993; Nikodem et al., 1998), the positive effect at 6 weeks postpartum was not replicated in other studies (Gordon et al., 1999; Hodnett et al., 2002) |

| Interaction strategies | Armstrong et al., 1999 Armstrong et al., 2000 Morrell et al., 2000 Reid et al., 2002 | These include extensive nursing home visits (Armstrong et al., 1999–2000) or additional support provided by trained postpartum workers (Morrell et al., 2000; Reid et al., 2002). They showed a reduction in depressive levels at 6 weeks postpartum compared to controls, but these results were not maintained at follow-up assessments. |

| Intervention | Author(s) | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Antenatal classes | Webster et al., 2003 | A randomized controlled trial showed no differences in depression levels between experimental and control groups at 16 weeks postpartum. |

| Early postpartum appointments | Serwint et al., 1991 Gunn et al., 1998 | Appointments were delivered 2–6 weeks postpartum in order to prevent postpartum depression and appeared to be only slightly effective in reducing depressive levels compared to controls. |

| Educational strategies | Okano et al., 1998 Heh et al., 2003 Hayes et al., 2001 | In two trials they were successful in decreasing the severity of postpartum depression and the time between onset of depressive symptoms and seeking professional help (Okano et al., 1998; Heh et al., 2003). However, a larger trial failed to replicate the result (Hayes et al., 2001). |

| Intervention | Description |

|---|---|

| Couples and marriage education programs | Changing attitudes and dispeling myths about marriage and teach relationship skills, especially related to communication and conflict resolution for adults at various life stages: single, dating, engaged, newly married, marriage in crisis, and those who are remarried. |

| Relationship education for students | Teaching middle and high school students about skills for building successful relationships and marriages. |

| Fatherhood programs | Promoting the importance of fatherhood and helping fathers to become more involved with their children. They encompass job training and placement, child support payment assistance, peer support groups, parenting classes, legal assistance, and individual counseling. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Comacchio, C.; Antolini, G.; Ruggeri, M.; Colizzi, M. Gender-Oriented Mental Health Prevention: A Reappraisal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031493

Comacchio C, Antolini G, Ruggeri M, Colizzi M. Gender-Oriented Mental Health Prevention: A Reappraisal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031493

Chicago/Turabian StyleComacchio, Carla, Giulia Antolini, Mirella Ruggeri, and Marco Colizzi. 2022. "Gender-Oriented Mental Health Prevention: A Reappraisal" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031493

APA StyleComacchio, C., Antolini, G., Ruggeri, M., & Colizzi, M. (2022). Gender-Oriented Mental Health Prevention: A Reappraisal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031493