Health Care for People with Disabilities in the Unified Health System in Brazil: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

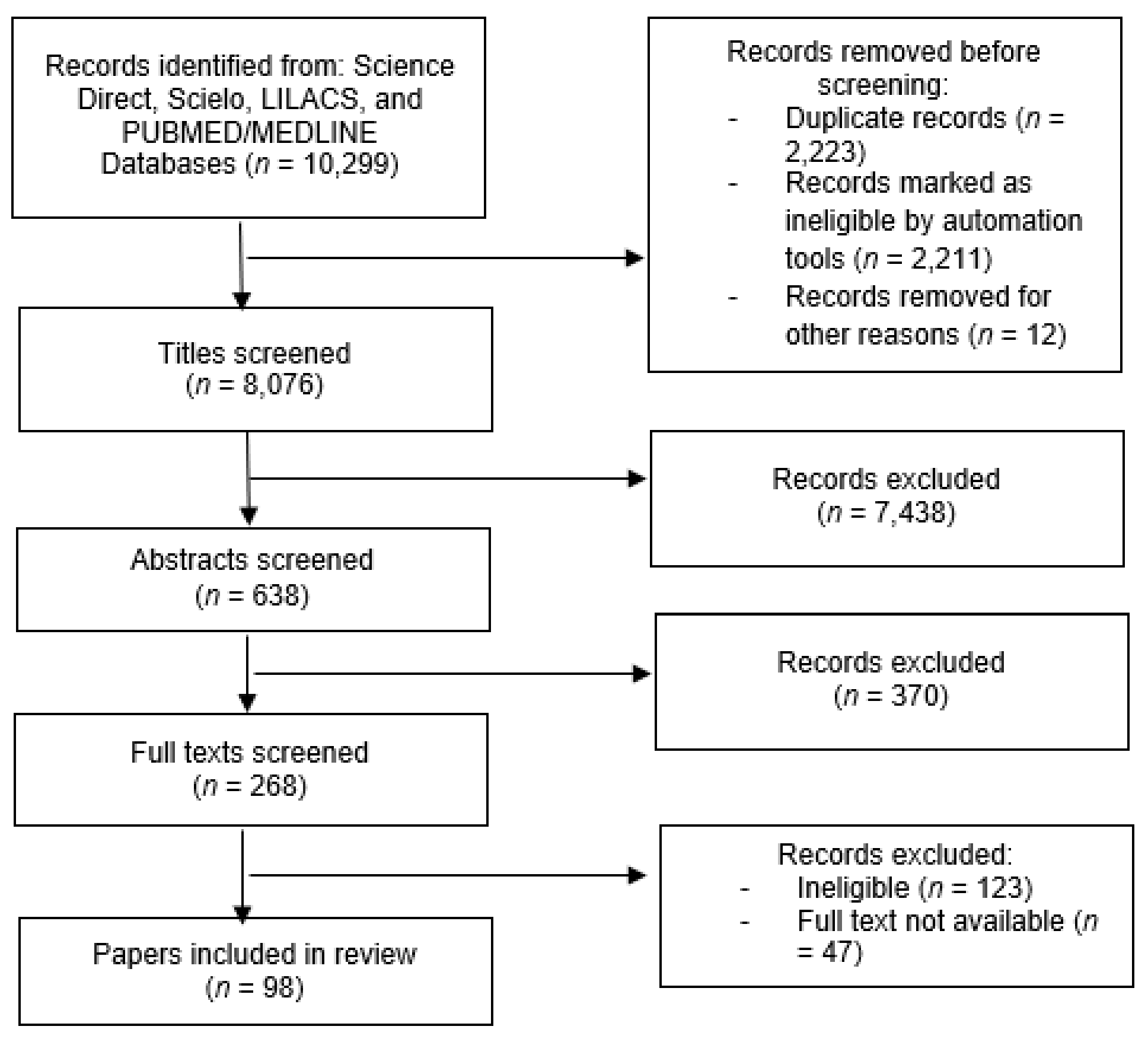

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. PNSPD Studies and Guidelines

3.3. Narrative Review of the Studies

3.3.1. Promoting the Quality of Life of People with Disabilities

3.3.2. Impairment Prevention

3.3.3. Comprehensive Health Care and Organization and Operation of Care Services for People with Disabilities

3.3.4. Expansion and Strengthening of Information Mechanisms

3.3.5. Human Resource Training

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Report on Disability; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper, H.; Heydt, P. The Missing Billion. Missing Billion, 2019. Available online: https://www.themissingbillion.org/the-report-2 (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Brazil. Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil. 1988. Available online: https://www.oas.org/es/sla/ddi/docs/acceso_informacion_base_dc_leyes_pais_b_1_en.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Brazil. Portaria Ministerial N° 1060; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2002. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2002/prt1060_05_06_2002.html (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Súmula do Programa “Viver Sem Limite”: Plano Nacional Dos Direitos Da Pessoa Com Deficiência. Cad. CEDES 2014, 34, 263–266. [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Santos, C.C.; Pedde, V.; Junior, N.K.; Renner, J.S. Política Pública, Deficiência Física, Concessão De Órteses, Próteses e Meios de Locomoção no Rio Grande do Sul: Período Pré/Pós Plano Viver Sem Limites. Interfaces Científicas Saúde Ambiente 2017, 5, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brasil; Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia E Estatística (IBGE). Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde 2019-ciclos de vida. 2021. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv101846.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Straus, S.E. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, A.T. Por dentro da estatística. Einstein. Educ. Contin. Saúde 2008, 6, 107–108. [Google Scholar]

- Galvão, C.R.C.; de Lima Barroso, B.I.; de Castro Grutt, D. A tecnologia assistiva e os cuidados específicos na concessão de cadeiras de rodas no Estado do Rio Grande do Norte/Assistive Technology and specific care in the granting of wheelchairs in Rio Grande do Norte state. Cad. Bras. Ter. Ocup. 2013, 21, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, R.C.B.; Oliver, F.C. A utilização de Tecnologia Assistiva na vida cotidiana de crianças com deficiência. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2013, 18, 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Castro, S.S.; Lefèvre, F.; Lefèvre, A.M.C.; Cesar, C.L.G. Acessibilidade aos serviços de saúde por pessoas com deficiência. Rev. Saúde Pública 2011, 45, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, F.L.J.D.S.; Holanda, C.M.D.A.; Quirino, M.A.B.; Nascimento, J.P.D.S.; Neves, R.D.F.; Ribeiro, K.S.Q.S.; Alves, S.B. Acessibilidade de pessoas com deficiência ou restrição permanente de mobilidade ao SUS. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2012, 17, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peixoto, M.V.D.S.; Santos, G.S.; Nobre, G.R.D.; Novais, A.P.D.S.; Reis, P.M. Análise da participação popular na política de atenção à saúde da pessoa com deficiência em Aracaju, Sergipe, Brasil. Interface Comun. Saúde Educ. 2018, 22, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobrega, J.D.; Munguba, M.C.; Pontes, R.J.S. Atenção à saúde e surdez: Desafios para implantação da rede de cuidados à pessoa com deficiência. Rev. Bras. Promoção Saúde 2017, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Siqueira, F.C.V.; Facchini, L.A.; Silveira, D.S.D.; Piccini, R.X.; Thumé, E.; Tomasi, E. Barreiras arquitetônicas a idosos e portadores de deficiência física: Um estudo epidemiológico da estrutura física das unidades básicas de saúde em sete estados do Brasil. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2009, 14, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vieira, C.M.; Caniato, D.G.; Yonemotu, B.P.R. Comunicação e acessibilidade: Percepções de pessoas com deficiência auditiva sobre seu atendimento nos serviços de saúde. RECIIS 2017, 11, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, K.P.; Costa, T.F.D.; Medeiros, T.M.D.; Fernandes, M.D.G.M.; França, I.S.X.D.; Costa, K.N.D.F.M. Estrutura interna de Unidades de Saúde da Família: Acesso para as pessoas com deficiência. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2016, 21, 3153–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aragão, A.E.D.A.; Pagliuca, L.M.F.; Macêdo, K.N.D.F.; DE ALMEIDA, P.C. Instalações sanitárias, equipamentos e áreas de circulação em Hospitais: Adequações aos deficientes físicos. Rev. Rene 2008, 9, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzarotto, I.H.E.K.; Gonçalves, C.G.D.O.; Bellia, C.G.D.L.; Moretti, C.A.M.; Iantas, M.R. Integralidade do cuidado na atenção à saúde auditiva do adulto no SUS: Acesso à reabilitação. Audiol. Commun. 2019, 24, e2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistella, L.R.; Juca, S.S.H.; Tateishi, M.; Oshiro, M.S.; Yamanaka, E.I.; Lima, E.; Ramos, V.D. Lucy Montoro Rehabilitation Network mobile unit: An alternative public healthcare policy. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2015, 10, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, L.R.; Pagliuca, L.M.F. Mapeamento da acessibilidade do portador de limitação física a serviços básicos de saúde. Esc. Anna Nery Rev. Enferm 2006, 10, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othero, M.B.; Ayres, J.R.D.C.M. Necessidades de saúde da pessoa com deficiência: A perspectiva dos sujeitos por meio de histórias de vida. Interface Comun. Saúde Educ. 2012, 16, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, M.; Correa Oliver, F. Pessoas com deficiência moradoras de bairro periférico da cidade de São Paulo: Estudo de suas necessidades. Cad. Ter. Ocup. 2013, 21, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, I.S.X.D.; Coura, A.S.; Sousa, F.S.D.; Almeida, P.C.D.; Pagliuca, L.M.F. Qualidade de vida em pacientes com lesão medular. Rev. Gaúch. Enferm. 2013, 34, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mattevi, B.S.; Bredemeier, J.; Fam, C.; Fleck, M.P. Quality of care, quality of life, and attitudes toward disabilities: Perspectives from a qualitative focus group study in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2012, 31, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miguel, J.H.D.S.; Novaes, B.C.D.A.C. Reabilitação auditiva na criança: Adesão ao tratamento e ao uso do aparelho de amplificação sonora individual. Audiol. Commun. 2013, 18, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guia, A.C.D.O.M.; Oliveira Neto, R.D.; Escarce, A.G.; Lemos, S.M.A. Rede de Atenção à Saúde Auditiva: Perspectiva do usuário. Distúrb. Comun. 2016, 28, 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Camargos, A.C.R.; Lacerda, T.T.B.D.; Barros, T.V.; Silva, G.C.D.; Parreiras, J.T.; Vidal, T.H.D.J. Relação entre independência funcional e qualidade de vida na paralisia cerebral. Fisioter. Mov. 2012, 25, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruschel, N.L.; Bonatto, A.S.; Teixeira, A.R. Reposição de próteses auditivas em programa de saúde auditiva. Audiol. Commun. 2019, 24, e2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.R.; Medeiros, D.D.S.; Ribeiro, G.M.; Rossi-Barbosa, L.A.R.; Caldeira, A.P. Satisfação com Aparelhos de Amplificação Sonora Individual entre usuários de serviços de saúde auditiva. Audiol. Commun. 2013, 18, 260–267. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorati, R.C.; Elui, V.M.C. Social determinants of health, inequality and social inclusion among people with disabilities. Rev. Latino Am. Enferm. 2015, 23, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, I.S.X.D.; Pagliuca, L.M.F.; Baptista, R.S.; França, E.G.D.; Coura, A.S.; Souza, J.A.D. Violência simbólica no acesso das pessoas com deficiência às unidades básicas de saúde. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2010, 63, 964–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Góes, F.G.B.; Cabral, I.E. A alta hospitalar de crianças com necessidades especiais de saúde e suas diferentes dimensões [Hospital discharge in children with special health care needs and its different dimensions]. Rev. Enferm. UERJ 2017, 25, e18684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamy, E.; Krauzer, I.; Hillesheim, C.; Silva, B.; Garghetti, F. A inserção da sistematização da assistência de enfermagem no contexto de pessoas com necessidades especiais. Rev. Pesqui. Cuid. Fundam. 2013, 5, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, K.D.M.; de Oliveira, W.I.F.; de Melo, L.O.M.; Alves, E.A.; Piuvezam, G.; Gama, Z.A.D.S. A qualitative study analyzing access to physical rehabilitation for traffic accident victims with severe disability in Brazil. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L.L.; De Lima Saintrain, M.V.; Vieira-Meyer, A.P.G.F. Access to dental public services by disabled persons. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Aragão, A.K.R.; Sousa, A.; Silva, K.; Vieira, S.; Colares, V. Acessibilidade da criança e do adolescente com deficiência na atenção básica de saúde bucal no serviço público: Estudo piloto. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clín. Integr. 2011, 11, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rosário, S.S.D.; de Lima Fernandes, A.P.N.; Batista, F.W.B.; Monteiro, A.I. Acessibilidade de crianças com deficiência aos serviços de saúde na atenção primária. Rev. Eletrônica Enferm. 2013, 15, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girondi, J.B.R.; dos Santos, S.M.A.; de Almeida Hammerschmidt, K.S.; Tristão, F.R. Acessibilidade de idosos com deficiência física na atenção primária. Estud. Interdiscip. Envelhec. 2014, 19, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, T.M.; Costa, K.N.F.M.; Costa, T.F.; Martins, K.P.; Dantas, T.R.A. Acessibilidade de pessoas com deficiência visual nos serviços de saúde [Health service accessibility for the visually impaired] [Accesibilidad para las personas con discapacidad visual en los servicios de salud]. Rev. Enferm. UERJ 2017, 25, 11424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pagliuca, L.M.F.; Aragão, A.E.D.A.; Almeida, P.C. Acessibilidade e deficiência física: Identificação de barreiras arquitetônicas em áreas internas de hospitais de Sobral, Ceará. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2007, 41, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marques, J.F.; Áfio, A.C.E.; Carvalho, L.V.D.; Leite, S.D.S.; Almeida, P.C.D.; Pagliuca, L.M.F. Acessibilidade física na atenção primária à saúde: Um passo para o acolhimento. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2018, 39, e2017-0009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, H.; de Paula Sousa, L.; de Lima Gonçalves, F.; de Lima Saintrain, M.V.; Vieira, A.P.G.F. Acesso à saúde bucal pública pelo paciente especial: A ótica do cirurgião-dentista. Rev. Bras. Promoç. Saúde 2014, 27, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Macêdo, G.L.D.; Lucena, E.E.D.S.; Lopes, I.K.R.; Batista, L.T.D.O. Acesso ao Atendimento Odontológico dos Pacientes Especiais: A Percepção de Cirurgiões-Dentistas da Atenção Básica. 2018. (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Ianni, A.; Pereira, P.C.A. Acesso da comunidade surda à rede básica de saúde. Saúde Soc. 2009, 18, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Freire, D.B.; Gigante, L.P.; Béria, J.U.; Palazzo, L.D.S.; Figueiredo, A.C.L.; Raymann, B.C.W. Acesso de pessoas deficientes auditivas a serviços de saúde em cidade do Sul do Brasil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2009, 25, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, W.C.A.; Silva, V.M.D.; Silva, R.A.D.; Ramos, R.L.; Figueiredo, N.M.A.D.; Branco, E.M.D.S.C.; Carreiro, M.D.A. Alta hospitalar de clientes com lesão neurológica incapacitante: Impreteríveis encaminhamentos para reabilitação. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2016, 21, 3161–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lima, M.L.C.D.; Deslandes, S.F.; Souza, E.R.D.; Lima, M.L.L.T.D.; Barreira, A.K. Análise diagnóstica dos serviços de reabilitação que assistem vítimas de acidentes e violências em Recife. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2009, 14, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Araujo Dantas, M.S.; da Nobrega, V.M.; dos Santos Fechine, C.P.N.; Torquato, I.M.B.; de Assis, W.D.; Collet, N. Atenção profissional à criança com paralisia cerebral e sua família [Professional care for children with cerebral palsy and their families] [Atención profesional al niño con parálisis cerebral ya su familia]. Rev. Enferm. UERJ 2017, 25, 18331. [Google Scholar]

- Quaresma, F.R.P.; Stein, A.T. Attributes of primary health care provided to children/adolescents with and without disabilities. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2015, 20, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guia, A.C.D.O.M.; Escarce, A.G.; Lemos, S.M.A. Autopercepção de saúde de usuários da Rede de Atenção à Saúde Auditiva. Cad. Saúde Coletiva 2018, 26, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.L.L.T.D.; Lima, M.L.C.D. Avaliação da implantação de uma Rede Estadual de Reabilitação Física em Pernambuco na perspectiva da Política Nacional de Redução da Morbimortalidade por Acidentes e Violência, 2009. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2013, 22, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Souza, M.A.P.D.; Dias, J.F.; Ferreira, F.R.; Mancini, M.C.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Sampaio, R.F. Características e demandas funcionais de usuários de uma rede local de reabilitação: Análise a partir do acolhimento. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2016, 21, 3277–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bevilacqua, M.C.; Morettin, M.; De Melo, T.M.; Amantini, R.C.B.; Martinez, M.A.N.D.S. Contribuições para análise da política de saúde auditiva no Brasil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Fonoaudiol. 2011, 16, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schultz, T.G.; do Carmo Alonso, C.M. Cuidado da criança com deficiência na Atenção Primária à Saúde. Cad. Ter. Ocup. UFSCar 2016, 24, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, M.; Batista, M.P.P.; Almeida, M.H.M.; Molini-Avejonas, D.R.; Oliver, F.C. Desafios do cuidado em rede na percepção de preceptores de um Pet Redes em relação à pessoa com deficiência e bebês de risco: Acesso, integralidade e comunicação/Challenges on network care considering the perceptions of preceptors of a Pet-Network regarding people with disabilities and at-risk infants: Access, comprehensiveness and communication. Cad. Bras. Ter. Ocup. 2017, 25, 519–532. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, M.H.; Rocha, E.F. Desbravando novos territórios: Incorporação da Terapia Ocupacional na estratégia da Saúde da Família no município de São Paulo e a sua atuação na atenção à saúde da pessoa com deficiência–no período de 2000–2006. Rev. Ter. Ocup. 2011, 22, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataglion, G.A.; Marinho, A. Familiares de crianças com deficiência: Percepções sobre atividades lúdicas na reabilitação. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2016, 21, 3101–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rezende, C.F.D.; Carvalho, S.A.D.S.; Maciel, F.J.; Oliveira, R.D.; Pereira, D.V.T.; Lemos, S.M.A. Rede de saúde auditiva: Uma análise espacial. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 81, 232–239. [Google Scholar]

- Surjus, L.T.D.L.E.S.; Onocko-Campos, R.T. Indicadores de avaliação da inserção de pessoas com deficiência intelectual na Rede de Atenção Psicossocial. Saúde Debate 2017, 41, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nicolau, S.M.; Schraiber, L.B.; Ayres, J.R.D.C.M. Mulheres com deficiência e sua dupla vulnerabilidade: Contribuições para a construção da integralidade em saúde. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2013, 18, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.M.R.; de Araújo Brito, D.B.; Alves, V.F.; Padilha, W.W.N. O acesso ao cuidado em saúde bucal para crianças com deficiência motora: Perspectivas dos cuidadores. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clín. Integr. 2011, 11, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de França, I.S.X.; Baptista, R.S.; da Silva Abrão, F.M.; Coura, A.S.; de França, E.G.; Pagliuca, L.M.F. O des-cuidar do lesado medular na atenção básica: Desafios bioéticos para as políticas de saúde. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2012, 65, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.C.; Czeresnia, D.; Paiva, S.M.; Campos, M.R.; Ferreira, E.F. Uso de serviços odontológicos por pacientes com síndrome de Down. Rev. Saúde Pública 2008, 42, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, T.E.C.; Friche, A.A.D.L.; Lemos, S.M.A. Percepção quanto à qualidade do cuidado de usuários da Rede de Cuidados à Pessoa com Deficiência. CoDAS 2019, 31, e20180102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubow, C.; Garcia, E.L.; Krug, S.B.F. Percepções sobre a Rede de Cuidados à Pessoa com Deficiência em uma Região de Saúde. Saúde Debate 2018, 42, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othero, M.B.; Dalmaso, A.S.W. Pessoas com deficiência na atenção primária: Discurso e prática de profissionais em um centro de saúde-escola. Interface Comun. Saúde Educ. 2009, 13, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.S.; de Andrade Trindade, J.L. Pet-saúde redes de atenção a pessoa com deficiência no contexto da atenção primária de saúde: Reflexões sobre a deficiência e funcionalidade do sujeito. Saúde Redes 2018, 4, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, M.H.M.D.; Pacheco, S.; Krebs, S.; Oliveira, A.M.; Samelli, A.; Molini-Avejonas, D.R.; Oliver, F.C. Primary health care assessment by users with and without disabilities. CoDAS 2017, 29, e20160225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vianna, N.G.; Cavalcanti, M.D.L.T.; Acioli, M.D. Princípios de universalidade, integralidade e equidade em um serviço de atenção à saúde auditiva. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2014, 19, 2179–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, T.E.O.; Leopardi, M.T.; Schoeller, S.D. Processo de trabalho em reabilitação de pessoas com deficiência física. Rev. Baiana Enferm. 2015, 29, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, M.C.; Broekman, G.V.D.Z.; Souza, R.O.D.D.; Lima, R.A.G.D.; Wernet, M.; Dupas, G. Rede de suporte da família da criança e adolescente com deficiência visual: Potencialidades e fragilidades. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2016, 21, 3213–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.D.S.; Machado, W.C.A. Referência e contrarreferência entre os serviços de reabilitação física da pessoa com deficiência: A (des) articulação na microrregião Centro-Sul Fluminense, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Physis 2016, 26, 1033–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schaik, E.E.; Souza, C.C.B.X.; Rocha, E.F. Reflexões sobre a atenção às crianças com deficiência na atenção. Rev. Ter. Ocup. Univ. São Paulo 2014, 25, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ursine, B.L.; Pereira, É.L.; Carneiro, F.F. Saúde da pessoa com deficiência que vive no campo: O que dizem os trabalhadores da Atenção Básica? Interface Comun. Saúde Educ. 2017, 22, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbag, J.C.; Lacerda, A.B.M.D. Rastreamento e monitoramento da Triagem Auditiva Neonatal em Unidade de Estratégia de Saúde da Família: Estudo-piloto. CoDAS 2017, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovere, N.C.; Lima, M.C.M.P.; Silva, I.R. A comunicação entre sujeitos surdos com diagnóstico precoce e com diagnóstico tardio e seus pares. Distúrb. Comun. 2018, 30, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rodrigues, G.R.I.; Loiola-Barreiro, C.M.; Pereira, T.; Pomilio, M.C.A. A triagem auditiva neonatal antecipa o diagnóstico e a intervenção em crianças com perda auditiva? Audiol. Commun. 2015, 20, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P.T.; Goldbach, M.G.; Monteiro, M.C.; Ribeiro, M.G. A triagem auditiva neonatal na Rede Municipal do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2015, 20, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Françozo, M.D.F.D.C.; Masson, G.A.; Rossi, T.R.D.F.; Lima, M.C.M.P.; Santos, M.F.C.D. Adesão a um programa de triagem auditiva neonatal. Saúde Soc. 2010, 19, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- da Silva, W.C.F.G.; Paschoal, M.R.; Cavalcanti, H.G. Análise da cobertura da triagem auditiva neonatal no Nordeste brasileiro. Audiol. Commun. 2017, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bertoldi, P.M.; Manfredi, A.K.S.; Mitre, E.I. Análise dos resultados da triagem auditiva neonatal no município de Batatais. Medicina 2017, 50, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, G.C.C.D.; Gagliardo, H.G.R.G. Atenção à saúde ocular de crianças com alterações no desenvolvimento em serviços de intervenção precoce: Barreiras e facilitadores. Rev. Bras. Oftalmol. 2016, 75, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Muniz, L.; Caldas Neto, S.D.S.; Gouveia, M.D.C.L.; Albuquerque, M.; Aragão, A.; Mercês, G.; Araújo, B. Conhecimento de ginecologistas e pediatras de hospitais públicos do Recife a respeito dos fatores de risco para surdez. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2010, 76, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, Z.Z.L.D.C.; Montilha, R.D.C.L.; Gasparetto, M.E.R.F.; Temporini, E.R.; Carvalho, K.M.M.D. Retinopatia diabética e deficiência visual entre pacientes de programa de reabilitação. Rev. Bras. Oftalmol. 2011, 70, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miranda, G.M.D.; Queiroga, B.A.M.D.; Lessa, F.J.D.; Leal, M.D.C.; Caldas Neto, S.D.S. Diagnóstico da deficiência auditiva em Pernambuco: Oferta de serviços de média complexidade-2003. Rev. Bras. Oftalmol. 2006, 72, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.M.; Raimundo, J.C.; Samelli, A.G.; Carvalho, A.C.M.D.; Matas, C.G.; Ferrari, G.M.D.S.; Bento, R.F. Idade no diagnóstico e no início da intervenção de crianças deficientes auditivas em um serviço público de saúde auditiva brasileiro. Arq. Int. Otorrinolaringol. 2012, 16, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, G.V.; de Oliveira Lomba, G.; Barbosa, T.A.; Reis, K.M.N.; Braga, P.P. Crianças com necessidades especiais de saúde de um município de Minas Gerais: Estudo descritivo. Rev. Enferm. Cent. Oeste Min. 2014, 4, 1310–1321. [Google Scholar]

- de Mello Rodrigues, S.; Aoki, M.; Oliver, F.C. Diagnóstico situacional de pessoas com deficiência acompanhadas em terapia ocupacional em uma unidade básica de saúde/Situational diagnosis of people with disabilities, receiving occupational therapy service in a basic health unit. Cad. Bras. Ter. Ocup. 2015, 23, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, G.C.; Schoeller, S.D.; Ramos, F.R.D.S.; Padilha, M.I.; Brehmer, L.C.D.F.; Marques, A.M.F.B. Perfil das pessoas com deficiência física e Políticas Públicas: A distância entre intenções e gestos. Ciên. Saúde Colet. 2016, 21, 3131–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bim, C.R.; Benato, B.S.; Vicentim, T.K. Perfil dos deficientes atendidos pelo programa de saúde da família. Do município de Guarapuava-Paraná. Ciên. Cuid. Saúde 2007, 6, 390–396. [Google Scholar]

- Sales, C.B.; Almeida, E.M.D.S.; Silva, G.K.; Alves, L.M. Perfil dos usuários do sistema de frequência modulada de um serviço de atenção à saúde auditiva. Audiol. Commun. 2019, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.D.R.; Pimentel, A.M. Pessoas com deficiência: Entre necessidades e atenção à saúde. Cad. Ter. Ocup. UFSCar 2012, 20, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, G.I.; Mendes, B.D.C.A.; Zupelari, M.M.; Pereira, I.M.T.B. Saúde auditiva no Brasil: Análise quantitativa do período de vigência da Política Nacional de Atenção à Saúde Auditiva. Distúrb. Comun. 2015, 27, 725–740. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, M.J.M.; Soares, J.D.S.F.; Bohusch, G. Usuários portadores de deficiência: Questões para a atenção primária de saúde. Rev. Baiana Enferm. 2014, 1, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, E.R.; Pagliuca, L.M.F.; Almeida, P.C.D. Aprendizagem do agente comunitário de saúde para identificar e cadastrar pessoas com deficiência. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2014, 27, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Soares, J.R.; Pagliuca, L.M.F.; Barbosa, E.M.G.; Maia, E.R. Aquisição de conhecimento para comunicação na consulta de enfermagem com o cego. Rev. Rene 2018, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, L.F.; Machado, F.C.; Lopes, M.M.; Oliveira, R.S.; Medeiros-Holanda, B.; Silva, L.B.; Kandratavicius, L. Conhecimento de Libras pelos médicos do Distrito Federal e atendimento ao paciente surdo. Rev. Bras. Educ. Méd. 2017, 41, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tedesco, J.D.R.; Junges, J.R. Desafios da prática do acolhimento de surdos na atenção primária. Cad. Saúde Pública 2013, 29, 1685–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de França, E.G.; Pontes, M.A.; Costa, G.M.C.; de França, I.S.X. Dificuldades de profissionais na atenção à saúde da pessoa com surdez severa. Cienc. Enferm. 2016, 22, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Trombetta, A.P.; Ramos, F.R.S.; Vargas, M.A.D.O.; Marques, A.M.B. Experiências da equipe de centro de reabilitação-o real do trabalho como questão ética. Esc. Anna Nery 2015, 19, 446–453. [Google Scholar]

- Missel, A.; Costa, C.C.D.; Sanfelice, G.R. Humanização da saúde e inclusão social no atendimento de pessoas com deficiência física. Trab. Educ. Saúde 2017, 15, 575–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sales, A.S.; Oliveira, R.F.D.; Araújo, E.M.D. Inclusion of persons with disabilities in a Reference Center for STD/AIDS of a town in Bahia, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2013, 66, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, V.D.S.L.; Santos, A.M.D. Knowledge and experience of Family Health Team professionals in providing healthcare for deaf people. Rev. CEFAC 2019, 21, e5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.M.; de Amorim Monteiro, L.P.; da Costa Monteiro, A.C.; Costa, I.D.C.C. Percepção das pessoas surdas sobre a comunicação no atendimento odontológico. Rev. Ciênc. Plur. 2017, 3, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.S.; Portes, A.J.F. Perceptions of deaf subjects about communication in Primary Health Care. Rev. Latinoam. Enferm. 2019, 27, e3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Level | Percentage of Eligible Studies (n = 98) |

|---|---|---|

| Study location | National | 2% |

| Regional/district | 4% | |

| State | 15% | |

| Local | 39% | |

| Municipal | 40% | |

| Region | Southeast | 44% |

| Northeast | 33% | |

| South | 18% | |

| Mixed/other | 5% | |

| Healthcare level | Primary healthcare | 39% |

| Specialist services | 54% | |

| Mixed/other | 7% | |

| Disability type | All | 40% |

| Hearing | 32% | |

| Visual | 5% | |

| Intellectual | 3% | |

| Multiple | 2% | |

| Participant type | Person with disability | 55% |

| Health professional | 26% | |

| Health unit | 7% | |

| Mixed/other | 12% | |

| Participant age | Child/adolescent | 16% |

| Adult/elderly | 29% | |

| Mixed | 12% | |

| Not applicable | 43% | |

| Participant gender | Mixed | 63% |

| Female only | 3% | |

| Not applicable | 34% | |

| Study method | Quantitative | 48% |

| Qualitative | 42% | |

| Mixed | 10% | |

| Data collection | Primary | 77% |

| Secondary | 16% | |

| Mixed | 7% | |

| Sample size | 1–100 | 61% |

| 101–1000 | 26% | |

| 1001+ | 10% | |

| NA | 3% | |

| Participant selection criteria specified | Yes | 81% |

| No/NA | 19% |

| PNSPD Guidelines | Studies | References |

|---|---|---|

| Promotion of quality of life for people with disabilities | 25% | [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] |

| Comprehensive health care for people with disabilities and organization and operation of care services for people with disabilities | 44% | [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] |

| Impairment prevention | 12% | [78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89] |

| Expansion and strengthening of information mechanisms | 8% | [90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97] |

| Training human resources for assistance to people with disabilities | 11% | [98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

da Cunha, M.A.O.; Santos, H.F.; de Carvalho, M.E.L.; Miranda, G.M.D.; de Albuquerque, M.d.S.V.; de Oliveira, R.S.; de Albuquerque, A.F.C.; Penn-Kekana, L.; Kuper, H.; Lyra, T.M. Health Care for People with Disabilities in the Unified Health System in Brazil: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031472

da Cunha MAO, Santos HF, de Carvalho MEL, Miranda GMD, de Albuquerque MdSV, de Oliveira RS, de Albuquerque AFC, Penn-Kekana L, Kuper H, Lyra TM. Health Care for People with Disabilities in the Unified Health System in Brazil: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031472

Chicago/Turabian Styleda Cunha, Márcia Andrea Oliveira, Helena Fernandes Santos, Maria Eduarda Lima de Carvalho, Gabriella Morais Duarte Miranda, Maria do Socorro Veloso de Albuquerque, Raquel Santos de Oliveira, Adrião Filho Cavalcanti de Albuquerque, Loveday Penn-Kekana, Hannah Kuper, and Tereza Maciel Lyra. 2022. "Health Care for People with Disabilities in the Unified Health System in Brazil: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031472

APA Styleda Cunha, M. A. O., Santos, H. F., de Carvalho, M. E. L., Miranda, G. M. D., de Albuquerque, M. d. S. V., de Oliveira, R. S., de Albuquerque, A. F. C., Penn-Kekana, L., Kuper, H., & Lyra, T. M. (2022). Health Care for People with Disabilities in the Unified Health System in Brazil: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031472