Moderating Effect of Help-Seeking in the Relationship between Religiosity and Dispositional Gratitude among Polish Homeless Adults: A Brief Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Religiosity and Homelessness

1.2. Gratitude and Homelessness

1.3. Religiosity, Gratitude and Help-Seeking among the Homeless

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Scale of Religious Attitude Intensity

2.4. Gratitude Questionnaire

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Correlations

3.3. Multicollinearity and Confounding Variables

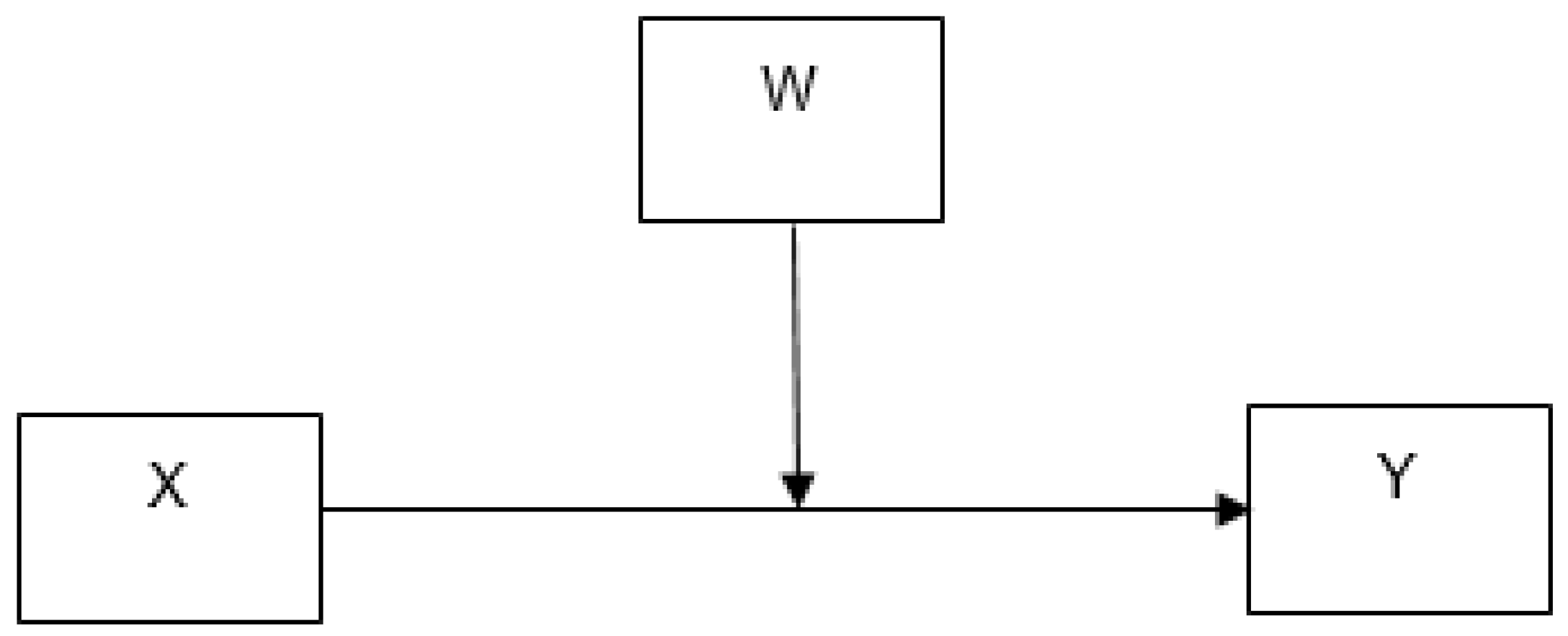

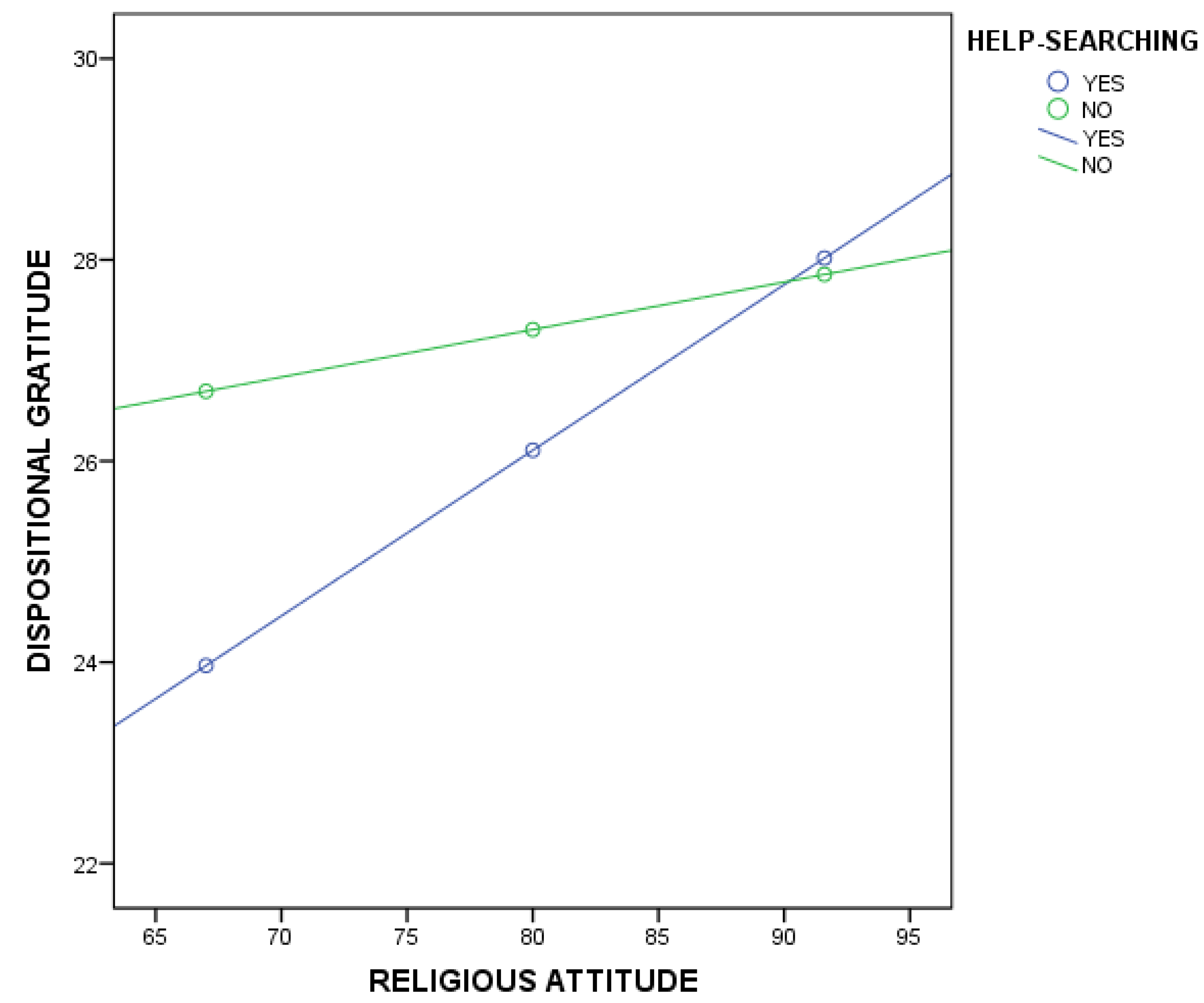

3.4. Moderation

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fitzpatrick, S. Explaining homelessness: A critical realist perspective. Hous. Theory Soc. 2005, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schields, T.G. Network new construction of homelessness: 1980–1993. Commun. Rev. 2001, 4, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronley, C. Unraveling the Social Construction of Homelessness. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2010, 20, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, J.; Muckle, W.; Masters, C. Homelessness and health. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2007, 177, 1065–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, R. Situation or Social Problem: The Influence of Events on Media Coverage of Homelessness. Soc. Probl. 2010, 57, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia-Lancheros, C.; Woodhall-Melnik, J.; Wang, R.; Hwang, S.W.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Durbin, A. Associations of resilience with quality of life levels in adults experiencing homelessness and mental illness: A longitudinal study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullen, J. Governing Homelessness: The Discursive and Institutional Construction of Homelessness in Australia. Hous. Theory Soc. 2015, 32, 218–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubits, D.; Shinn, M.; Wood, M.; Brown, S.R.; Dastrup, S.R.; Bell, S.H. What Interventions Work Best for Families who Experience Homelessness? Impact Estimates from the Family Options Study. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2018, 37, 735–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burak, A.; Ferenc, A. Defining and measuring of homelessness. Poland. Probl. Polityki Społ. 2021, 52, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Lu, C.J.; Lee, T.S.; Chen, M.; Liu, C.K.; Chen, C.L. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Metabolic Syndrome among the Homeless in Taipei City: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokonać Bezdomność–Program Pomocy Osobom Bezdomnym. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/pokonac-bezdomnosc-program-pomocy-osobom-bezdomnym-edycja-2021 (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Frankish, C.J.; Hwang, S.W.; Quantz, D. Homelessness and health in Canada: Research lessons and priorities. Can. J. Public Health 2005, 96, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, A. Private lives in public places: Loneliness of the homeless. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 72, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, M.J.; Grenier, G.; Sabetti, J.; Bertrand, K.; Clement, M.; Brochu, S. Met and unmet needs of homeless individuals at different stages of housing reintegration: A mixed-method investigation. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neate, S.L.; Philips, G.A. The challenging patient. In Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine; Cameron, P., Jelinek, G., Kelly, A.M., Brown, A., Little, M., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, Scottish, 2015; pp. 717–726. [Google Scholar]

- Trawver, K.R.; Oby, S.; Kominkiewicz, L.; Kominkiewicz, F.B.; Whittington, K. Homelessness in America: An Overview. In Homelessness Prevention and Intervention in Social Work. Policies, Programs, and Practices; Larkin, H., Aykanian, A., Streeter, C.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, B.; Meert, H.; Doherty, J. Third Review of Statistics on Homelessness in Europe. Developing an Operational Definition of Homelessness; Feantsa: Brussel, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shlay, A.B.; Rossi, P.H. Social Science Research and Contemporary Studies of Homelessness. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1992, 18, 129–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, M.; Byrne, K.; Fu, R.; Lipmann, B.; Mirabelli, F.; Rota-Bartelink, A.; Ryan, M.; Shea, R.; Watt, H.; Warnes, A.M. The Causes of Homelessness in Later Life: Findings From a 3-Nation Study. J. Gerontol. 2005, 60, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinn, M. International Homelessness: Policy, Socio-Cultural, and Individual Perspectives. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, A.; Horita, R.; Sado, T.; Mizutani, S.; Watanabe, T.; Uehara, R.; Yamamoto, M. Causes of homelessness prevalence: Relationship between homelessness and disability. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 71, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, D.; Lynch, P. Housing, homelessness and human rights. Aust. J. Hum. Rights 2004, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Russotto, S.; Zamperini, A.; De Leo, D. Addiction and religiosity in facing suicide: A qualitative study on meaning of life and death among homeless people. Ment. Illness 2018, 10, 7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peterie, M.; Bielefeld, S.; Marston, G.; Mendes, P.; Humpage, L. Compulsory income management: Combatting or compounding the underlying causes of homelessness? Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, R.G.; Biswas-Diener, R.; Lehman, D.R. Self-perceived strengths among people who are homeless. J. Posit. Psychol. 2012, 7, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rew, L.; Horner, S.D. Personal Strengths of Homeless Adolescents Living in a High-Risk Environment. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2003, 26, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klop, H.T.; Evenblij, K.; Gootjes, J.R.G.; de Veer, A.J.E.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D. Care avoidance among homeless people and access to care: An interview study among spiritual caregivers, street pastors, homeless outreach workers and formerly homeless people. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarz, K.; Huzarek, T.; Tykarski, S. Tożsamość Zagubiona: Oblicza Bezdomności XXI Wieku; Wydawnictwo Bernardinum: Pelplin, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, K.M. Circumstances, Religiosity/Spirituality, Resources and Mental Health Outcomes Among Homeless Adults in Northwest Arkansas. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 2018, 10, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galen, L.W.; Kloet, J.D. Mental Well-Being in the Religious and the Non-Religious: Evidence for a Curvilinear Relationship. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2011, 14, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szcześniak, M.; Bielecka, G.; Bajkowska, I.; Czaprowska, A.; Madej, D. Religious/Spiritual Struggles and Life Satisfaction among Young Roman Catholics: The Meditating Role of Gratitude. Religions 2019, 10, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernándes, M.B.; Rosell, J. An Analysis of the Relationship Between Religiosity and Psychological Well-Being in Chilean Older People Using Structural Equation Modeling. J. Relig. Health 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocson, R.M.; Garcia, A.S. Religiosity and spirituality among Filipino mothers and father: Relations to psychological well-being and parenting. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krok, D. The Religious Meaning System and Subjective Well-Being: The Mediational Perspective of Meaning in Life. Arch. Psychol. Relig. 2014, 36, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szocik, K.; Van Eyghen, H. Revising Cognitive and Evolutionary Science of religion: Religion as an Adaptation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, B.R.; Bergeman, C. How Does Religiosity Enhance Well-Being? The Role of Perceived Control. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2011, 3, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N.M.; Fincham, F.D.; Braithwaite, S.R.; Graham, S.M.; Beach, S.R.H. Can Prayer Increase Gratitude? Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2009, 1, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulbure, B.T. Appreciating the Positive Protects us from Negative Emotions: The Relationship between Gratitude, Depression and Religiosity. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 187, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J. Korean Christian Young Adults’ Religiosity Affects Post-Traumatic Growth: The Mediation Effects of Forgiveness and Gratitude. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 3967–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounding, K.; Hart, K.E.; Hibbard, S.; Carroll, M. Emotional Resilience in Young Adults Who Were Reared by Depressed Parents: The Moderating Effects of Offspring Religiosity/Spirituality. J. Spiritual Ment. Health 2011, 13, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, J.L. Spirituality and Homelessness: Implications for Pastoral Counseling. Pastoral Psychol. 2014, 63, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.A.; Kort-Butler, L.A.; Swendener, A. The Effect of Victimization, Mental Health, and Protective Factors on Crime and Illicit Drug Use Among Homeless Young Adults. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Testoni, I.; Russotto, S.; Zamperini, A.; Pompele, S.; De Leo, D. Neither God nor others: A qualitative study of strategies for avoiding suicide among homeless people. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2020, 42, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, J.; Walls, E.; Wisneski, H. Religion and religiosity: Protective or harmful factors for sexual minority youth? Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2013, 16, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.M.; Wu, Q.; Dyrness, G.; Spruijt-Metz, D. Perceptions of Faith and Outcomes in Faith-Based Programs for Homeless Youth: A Grounded Theory Approach. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2007, 33, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.J.; Ahmed, S.R.; Tompsett, C.J.; Jozefowicz-Simbeni, D.M.H.; Toro, P.A. Community violence and externalizing problems: Moderating effects of race and religiosity in emerging adulthood. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 36, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, D.C.; Collins, S.E.; Nelson, L.A.; Serafini, K.; Clifasefi, S.L.; Donovan, D.M. Religious and Spiritual Practices Among Homeless Urban American Indians and Alaska Natives with Severe Alcohol Problems. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 2017, 24, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumsteiger, R.; Chenneville, T. Challenges to the Conceptualization and Measurement of Religiosity and Spirituality in Mental Health Research. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 2344–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, D.; Sorgente, A.; Iannello, P.; Antonietti, A. The Role of Spirituality and Religiosity in Subjective Well-Being of Individuals with Different Religious Status. Front Psychol. 2019, 10, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, A.; Pargament, K.I.; Jewell, T.; Swank, A.B.; Scott, E.; Emery, E.; Rye, M. Marriage and the Spiritual Realm: The Role of Proximal and Distal Religious Constructs in Marital Functioning. J. Fam. Psychol. 1999, 13, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwutikornwanich, A. Belief in the Afterlife, Death Anxiety, and Life Satisfaction of Buddhists and Christians in Thailand: Comparison between Different Religiosity. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, L.M.; Possetti, J.G.; Silva, M.T.; Santos, G.S.; Lucchetti, G.; Moreira-Almeida, A.; Guimaraes, M.V.C. The role of spirituality and religiosity on suicidal ideation of homeless people in a large Brazilian urban center. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.; Rosenheck, R.A. Religiosity Among Adults who are Chronically Homeless: Association with Clinical and Psychosocial Outcomes. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 1222–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.; Rosenheck, R.A.; Kasprow, W.J.; McGuire, J.F. Do Faith-Based Residential Care Services Affect the Religious Faith and Clinical Outcomes of Homeless Veterans? Community Ment. Health J. 2011, 48, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torchalla, I.; Li, K.; Strehlau, V.; Linden, I.A.; Krausz, M. Religious Participation and Substance Use Behaviors in a Canadian Sample of Homeless People. Community Ment. Health J. 2014, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, C.A.; Gulbrandsen, C.L. Spirituality as Strength: Reflections of Homeless Women in Canada. Int. J. Relig. Spiritual Soc. 2014, 3, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, D.R.; Moser, S.E.; Shafer, M. Spirituality and Mental Health among Homeless Mothers. Soc. Work Res. 2013, 36, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinson, T.; Hurt, K.; Hughes, A.K. “I Overcame That with God’s Hand on Me”: Religion and Spirituality Among Older Adults to Cope with Stressful Life Situations. J. Relig. Spiritual Soc. Work. Soc. Thought. 2015, 34, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows-Oliver, M. Homeless Adolescent Mothers: A Metasynthesis of Their Life Experiences. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2006, 21, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Asante, K.O. Factors that Promote Resilience in Homeless Children and Adolescents in Ghana: A Qualitative Study. Behav Sci. 2019, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovett, K.L.; Weisz, C. Religion and Recovery Among Individuals Experiencing Homelessness. J. Relig. Health 2020, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oviedo, L. Meaning and Religion: Exploring Mutual Implications. Sci. Fides 2019, 7, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindra, I.W.; Jindra, M.; DeGenero, S. Contrasts in Religion, Community, and Structure at Three Homeless Shelters: Changing Lives; Routledge: Great Britain, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scranton, C.J. Relationship Between Horizontal Gratitude, Vertical Gratitude, Subjective Well-Being, and Spiritual Well-Being in the Sheltered Homeless. 2017. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/946b0be95c9089a0b0d198cf8aadb4e8/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Watts, B. Homelessness, Empowerment and Self-reliance in Scotland and Ireland: The Impact of Legal Rights to Housing for Homeless People. J. Soc. Policy 2014, 43, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, J.R.; DeForge, B.R. Social Stigma and Homelessness: The Limits of Social Change. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2012, 22, 929–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, S. Homeless Men and Homeless Women: The Gender Gap. Urban Soc. Change Rev. 1984, 17, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Piechowicz, M.; Piotrowski, A.; Pastwa-Wojciechowska, B. The Social Rehabilitation of Homeless Women with Children. Acta Neuropsychol. 2014, 14, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, D.E. A Portrait of Older Homeless Men: Identifying Hopelessness and Adaptation. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 1995, 4, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturman, N.; Matheson, D. ‘I just hope they take it seriously’: Homeless men talk about their health care. Aust. Health Rev. 2020, 44, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraino, A.; Krema, G.; Williams, S.M.; Ferrari, J.R. “Hour of HOPE”: A Spiritual Prayer Program for Homeless Adults. Univers. J. Psychol. 2014, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, A.L.; Nyamathi, A.; Greengold, B.; Slagle, A.; Koniak-Griffin, D.; Khalilifard, F.; Getzoff, D. Health-Seeking Challenges Among Homeless Youth. Nurs. Res. 2010, 59, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, R. Bringing palliative care to the homeless. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2011, 183, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Williams, N.R.; Lindsey, E.W.; Kurtz, P.D.; Jarvis, S. From Trauma to Resiliency: Lessons from former runaway and homeless youth. J. Youth Stud. 2001, 4, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxley, D.P.; Washington, O.G.M. Souls in Extremis: Enacting Processes of Recovery from Homelessness Among Older African American Women. J. Relig. Health 2016, 55, 1038–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, S.J.; Quinton, M.L.; Holland, M.J.G.; Parry, B.J.; Cumming, J. The Experiences of Homeless Youth When Using Strengths Profiling to Identify Their Character Strengths. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rew, L.; Slesnick, N.; Johnson, K.; Aguilar, R.; Cengiz, A. Positive attributes and life satisfaction in homeless youth. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 100, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, S.; Begley, A.; Mackintosh, B.; Kerr, D.A.; Jancey, J.; Caraher, M.; Whelan, J.; Pollard, C.M. Gratitude, resignation and desire for dignity: Lived experience of food charity recipients and their recommendations for improvement, Perth, Western Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 2831–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, V.F.; St-Denis, N.; Walsh, C.A.; Hewson, J. Creating a Sense of Place after Homelessness: We Are Not “Ready for the Shelf”. J. Aging Environ. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, N.; Błachnio, A.; Aminikhoo, M. The relations of gratitude to religiosity, well-being, and personality. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2018, 21, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A.; Kneezel, T.T. Giving Thanks: Spiritual and Religious Correlates of Gratitude. J. Psychol. Christ. 2005, 24, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, R.; Desmond, S.A.; Palmer, Z.D. Being Thankful: Examining the Relationship Between Young Adult Religiosity and Gratitude. J. Relig. Health 2014, 54, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, N. Religious Involvement, Gratitude, and Change in Depressive Symptoms Over Time. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2009, 19, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmons, R.A.; Crumpler, C.A. Gratitude as a Human Strength: Appraising the Evidence. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 19, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A. The Psychology of Gratitude: An Introduction. In The Psychology of Gratitude; Emmons, R.A., McCullough, M.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, A.; Joseph, S.; Linley, A. Gratitude – Parent of All Virtues. Psychologist 2007, 20, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H.G. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012, 8, 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malin, H.; Liauw, I.; Damon, W. Purpose and Character Development in Early Adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 1200–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, R.; Stephens, L.S. Clients’ Reactions to Religious Elements at Congregation-Run Feeding Establishments. Nonprofit Volunt. Sec. Q. 2005, 34, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Barusch, A. Religion, Adversity and Age: Religious Experiences of Low-Income Elderly Women. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 1999, 26, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman, S.; Bierman, A. The Role of Divine Beliefs in Stress Processes. In Toward a Sociological Theory of Religion and Health; Blasi, A., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer, M.K. Religion and Health in Japan: Past Research, New Findings, and Future Directions. In Toward a Sociological Theory of Religion and Health; Blasi, A., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011; p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, N. Stress, Religious-based Coping, and Physical Health. In Toward a Sociological Theory of Religion and Health; Blasi, A., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood, D.; Thomas, K. Conceptual measurement framework for help-seeking for mental health problems. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2012, 5, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seryczyńska, B.; Oviedo, L.; Roszak, P.; Saarelainen, S.M.K.; Inkilä, H.; Torralba Albaladejo, J.; Anthony, F.V. Religious Capital as a Central Factor in Coping with the COVID-19: Clues from an International Survey. Eur. J. Sci. Theol. 2021, 17, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Śliwak, J.; Bartczuk, R. Skala Intensywności Postawy Religijnej. In Psychologiczny Pomiar Religijności; Jarosz, M., Ed.; Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL: Lublin, Poland, 2011; pp. 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, S.; Huber, O.W. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 2012, 3, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szcześniak, M.; Światek, A.H.; Świątek, M.A.; Rodzeń, W. Positive Downstream Indirect Reciprocity Scale (PoDIRS-6): Construction and Psychometric Characteristics. Curr. Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Emmons, R.A.; Tsang, J. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossakowska, M.; Kwiatek, M. Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza do badania wdzięczności GQ-6. Przegląd Psychol. 2014, 57, 503–514. [Google Scholar]

- Szcześniak, M.; Soares, E. Are Proneness to Forgive, Optimism and Gratitude Associated with Life Satisfaction? Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 42, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszek, K.; Lasota, A. Gratitude and Its Measurement—The Polish adaptation of the Grat – R Questionnaire. Czas. Psychol. 2018, 24, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przepiorka, A.; Sobol-Kwapinska, M. People with Positive Time Perspective are More Grateful and Happier: Gratitude Mediates the relationship Between Time Perspective and Life Satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, L.F. Statistical Analyses for Language Assessment; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Method. 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost-Dubrow, R.; Dunham, Y. Evidence for a relationship between trait gratitude and prosocial behaviour. Cogn. Emot. 2017, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P.C.; Woodward, K.; Stone, T.; Kolts, R.L. Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2003, 31, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenthal, K.M.; MacLeod, A.K.; Cinnirella, M. Are women more religious than men? Gender differences in religious activity among different religious groups in the UK. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2002, 32, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collett, J.L.; Lizardo, O. A Power-Control Theory of Gender and Religiosity. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2009, 48, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, L. The Gender Pray Gap: Wage Labor and the Religiosity of High-Earning Women and Men. Gend. Soc. 2016, 30, 643–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Mishra, A.; Breen, W.E.; Froh, J.J. Gender Differences in Gratitude: Examining Appraisals, Narratives, the Willingness to Express Emotions, and Changes in Psychological Needs. J. Pers. 2009, 77, 691–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algoe, S.B.; Gable, S.L.; Maisel, N.C. It’s the little things: Everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Pers. Relatsh. 2010, 17, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessler, R.; Rosenheck, R.; Gamache, G. Gender Differences in Self-Reported Reasons for Homelessness. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2001, 10, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.E.; Szymkowiak, D.; Culhane, D. Gender Differences in Factors Associated with Unsheltered Status and Increased Risk of Premature Mortality among Individuals Experiencing Homelessness. Women’s Health Issues 2017, 27, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, M.; Abdelhafez, D. NGO-Public Administration Relationships in Tackling the Homelessness Problem in the Czech Republic and Poland. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, R.E.; Burnett, J.J.; Howell, R.D. On the meaning and measurement of religiosity in consumer research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1986, 14, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergan, A.; McConatha, J.T. Religiosity and Life Satisfaction. Act. Adapt. Aging 2012, 24, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, M.; Nadorff, D.K.; Lantz, E.D.; McKay, I.T. Religiosity and depressive symptoms in older adults compared to younger adults: Moderating by age. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 238, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopik, W.J.; Newton, N.J.; Ryan, L.H.; Kashdan, T.B.; Jarden, A.J. Gratitude across the life span: Age differences and links to subjective well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 14, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allemand, M.; Hill, P.L. Gratitude from Early Adulthood to Old Age. J. Pers. 2014, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naito, T.; Washizu, N. Gratitude in Life-span Development: An Overview of Comparative Studies between Different Age Groups. J. Behav. Sci. 2019, 14, 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tudge, J.R.H.; Freitas, L.B.L.; Mokrova, I.L.; Wang, Y.C.; O’Biren, M. The Wishes and Expression of Gratitude of Youth. Paideia 2015, 25, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fallot, R.D. Spirituality in Trauma Recovery for People with Severe Mental Disorders. In Sexual Abuse in the Lives of Women Diagnosed with Serious Mental Illness; Harris, M., Landis, C.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. 337. [Google Scholar]

- Jasiński, J.L.; Wesely, J.K.; Wright, J.D.; Mustaine, E.E. Hard Lives, Mean Streets. Violence in the Lives of Homeless Women; University Press of New England: Lebanon, NH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, L.M.R.; Dickinson, S.; Esposito, E.; Connolly, J.; Bonilla, L. Common Themes in the Life Stories of Unaccompanied Homeless Youth in High School: Implications for Educators. Contemp. School Psychol. 2017, 22, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.D. Homeless. Narratives from the Streets; McFarland and Company: Jefferson, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius, C.; Chambers, D.; Cowan, B.; Coyle, D. Young People Seeking Help Online for Mental Health: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 26, e13524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.I.; Park, C.L. Merely a Defense? The Variety of Religious Means and Ends. J. Soc. Issues 1995, 51, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.C.; Passik, S.; Kash, K.M.; Russak, S.M.; Gronert, M.K.; Sison, A.; Lederberg, M.; Fox, B.; Baider, L. The Role of religious and Spiritual Beliefs in Coping with Malignant Melanoma. Psycho-Oncology 1999, 8, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Yeh, Y.C. How Gratitude Influences Well-Being: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lens, V.; Nugent, M.; Wimer, C. Asking for Help: A Qualitative Study of Barriers to Help Seeking in the Private Sector. J. Cos. Soc. Work Res. 2018, 9, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.; Fisher, C.M.; Pillemer, J. IDEO’s Culture of Helping: By making collaborative generosity the norm, the design firm has unleashed its creativity. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 92, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, R.C. Foreword. In The Psychology of Gratitude; Emmons, R.A., McCullough, M.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. V–XI. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, B.L.; Rueda, J. In Defense of Posthuman Vulnerability. Sci. Fides 2021, 9, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, A. Personality and Help Seeking: Autonomous versus Dependent Seeking of Help. In Sourcebook of Social Support and Personality; Pierce, G.R., Lakey, B., Sarason, I.G., Sarason, B.R., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 379–407. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.A.; Ahmed, M.; Bhatti, O.K.; Farooq, W. Gratitude and Its Conceptualization: An Islamic Perspective. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 1740–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, N.; Emmons, R.A.; Ironson, G. Benevolent Images of God, Gratitude, and Physical Health Status. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 1503–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, N.; Hayward, R.D. Humility, Compassion, and Gratitude to God: Assessing the Relationships Among Key Religious Virtues. Psycholog. Relig. Spiritual. 2015, 7, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.K. Promoting Intrinsic Religiosity in Minority-Majority Relationships for Healthy Democratic Life. J. Psychosoc. Res. 2014, 9, 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham, F.D.; May, R.W. Generalized Gratitude and Prayers of Gratitude in Marriage. J. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scales | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious Attitude Intensity | 78.26 | 18.54 | −0.827 | −0.731 |

| Dispositional Gratitude | 26.28 | 7.02 | 2.359 | 0.799 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szcześniak, M.; Szmuc, K.; Tytonik, B.; Czaprowska, A.; Ivanytska, M.; Malinowska, A. Moderating Effect of Help-Seeking in the Relationship between Religiosity and Dispositional Gratitude among Polish Homeless Adults: A Brief Report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031045

Szcześniak M, Szmuc K, Tytonik B, Czaprowska A, Ivanytska M, Malinowska A. Moderating Effect of Help-Seeking in the Relationship between Religiosity and Dispositional Gratitude among Polish Homeless Adults: A Brief Report. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031045

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzcześniak, Małgorzata, Katarzyna Szmuc, Barbara Tytonik, Anna Czaprowska, Mariia Ivanytska, and Agnieszka Malinowska. 2022. "Moderating Effect of Help-Seeking in the Relationship between Religiosity and Dispositional Gratitude among Polish Homeless Adults: A Brief Report" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031045

APA StyleSzcześniak, M., Szmuc, K., Tytonik, B., Czaprowska, A., Ivanytska, M., & Malinowska, A. (2022). Moderating Effect of Help-Seeking in the Relationship between Religiosity and Dispositional Gratitude among Polish Homeless Adults: A Brief Report. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1045. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031045