Where to Retire? Experiences of Older African Immigrants in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Trustworthiness and Rigor

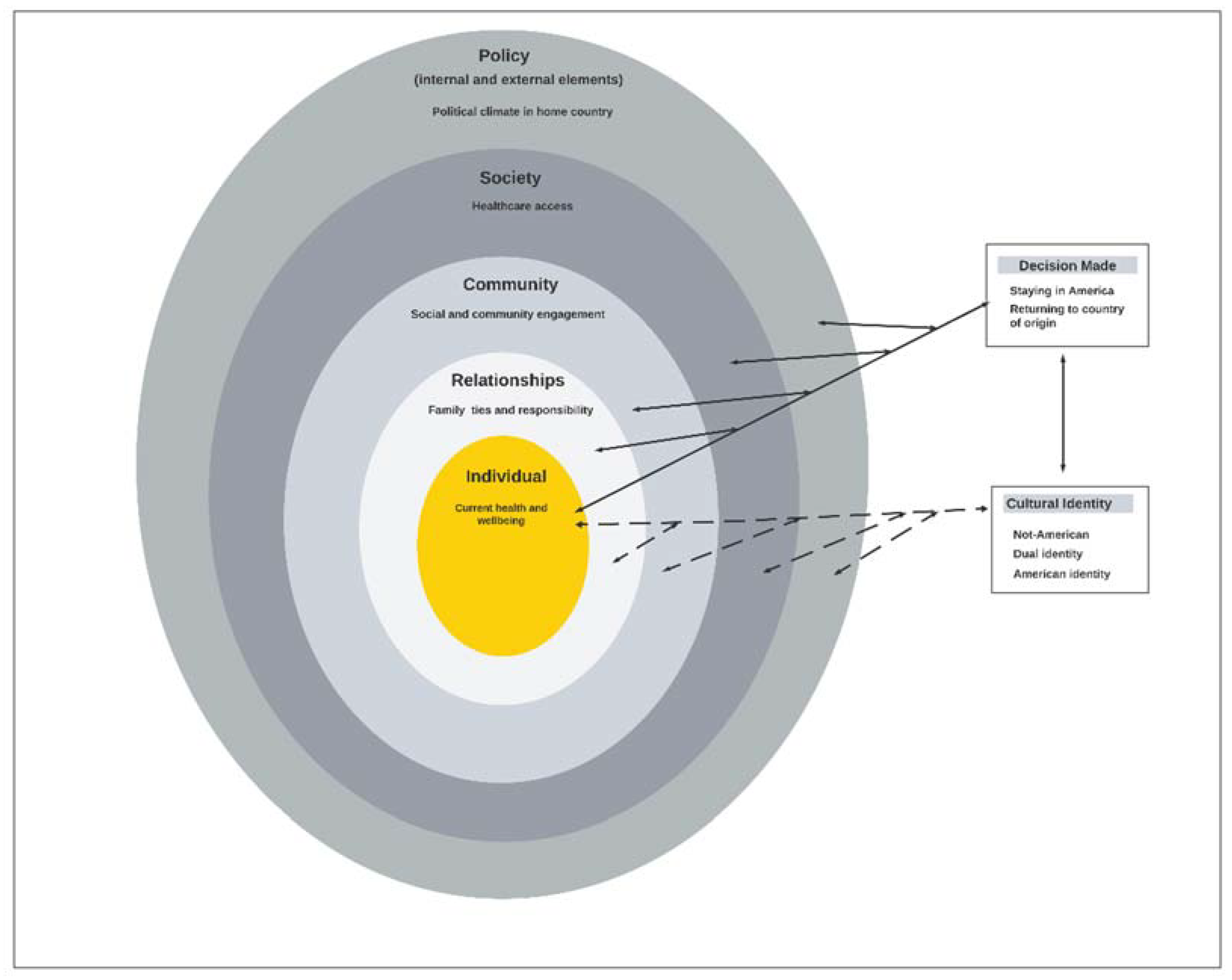

3. Results

3.1. Cultural Identity

3.2. Decision Making

3.3. Decision Made

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Older African Immigrant Health Study Interview Guide

| Phase 1 |

|

|

|

|

| Phase 2 |

|

|

|

|

| Phase 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Phase 4 |

|

|

| Phase 5 |

|

|

|

|

| Follow up questions to the Interviewer |

|

|

References

- Mizoguchi, N.; Walker, L.; Trevelyan, E.; Ahmed, B. The Older Foreign-Born Population in the United States: 2012–2016. Community Survey Reports; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: Https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/acs/acs-42.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Colby, S.L.; Ortman, J.M. Projections of the Size and Composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060. Current Population Reports, 2015, P25-1143. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.html (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Camarota, S.; Zeigler, K. Immigrants Are Coming to America at Older Ages. CIS.org, 1 July 2019. Available online: https://cis.org/Report/Immigrants-Are-Coming-America-Older-Ages (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Carr, S.; Tienda, M. Family Sponsorship and Late-Age Immigration in Aging America: Revised and Expanded Estimates of Chained Migration. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2013, 32, 825–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mather, M.; Scommegna, P.; Kilduff, L. Fact Sheet: Aging in the United States—Population Reference Bureau. 2019. Available online: https://www.prb.org/aging-unitedstates-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- U.S. Census Bureau & American Community Survey. American Community Survey. 2014. Available online: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_14_1YR_S0504&prodType=table (accessed on 28 December 2016).

- Anderson, M. African Immigrant Population in U.S. Steadily Climbs. Pew Research Center, 14 February 2017. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/02/14/african-immigrant-population-in-u-s-steadily-climbs/ (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- BBC.Co.UK. BBC Bitsize-Migration Trends. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z8x6wxs/revision/2 (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- USA Facts. Why Do People Immigrate to the US? USA Facts.org, 28 May 2020. Available online: https://usafacts.org/articles/why-do-people-immigrate-us/?share=undefined#immigration-by-reason (accessed on 8 January 2010).

- BBC News. African Migration: Five Things We’ve Learnt. BBC News, 26 March 2019. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-47705944 (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- OECD. How’s Life? 2013: Measuring Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. At Least a Million Sub-Saharan Africans Moved to Europe Since 2010. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project, 22 March 2018. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/03/22/at-least-a-million-sub-saharan-africans-moved-to-europe-since-2010/ (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Dupre, M.E.; Gu, D.; Vaupel, J. Survival Differences among Native-Born and Foreign-Born Older Adults in the United States. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, K.S.; Eschbach, K. Aging, Migration, and Mortality: Current Status of Research on the Hispanic Paradox. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2005, 60, S68–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.M.; Steffen, P.; Smith, T.B. Hispanic Mortality Paradox: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Longitudinal Literature. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e52–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venters, H.; Adekugbe, O.; Massaquoi, J.; Nadeau, C.; Saul, J.; Gany, F. Mental Health Concerns Among African Immigrants. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2011, 13, 795–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venters, H.; Gany, F. African Immigrant Health. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2011, 13, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi, C. Effects of Immigration and Age on Health of Older People in the United States. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2009, 29, 697–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coulon, A. Where do immigrants retire to? IZA World Labor 2016, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palloni, A.; Arias, E. Paradox lost: Explaining the hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography 2004, 41, 385–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, E.F.; Nuru-Jeter, A.; Richardson, D.; Raza, F.; Minkler, M. The Hispanic Paradox and Older Adults’ Disabilities: Is There a Healthy Migrant Effect? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 1786–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubernskaya, Z.; Bean, F.D.; Van Hook, J. (Un)Healthy Immigrant Citizens. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2013, 54, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, T.G.; Hagos, R. Race and the Healthy Immigrant Effect. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2020, 31, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, K.S.; Rote, S. The Healthy Immigrant Effect and Aging in the United States and Other Western Countries. Gerontologist 2018, 59, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, N.K.; Elo, I.T.; Engelman, M.; Lauderdale, D.S.; Kestenbaum, B.M. Life Expectancy Among U.S.-born and Foreign-born Older Adults in the United States: Estimates from Linked Social Security and Medicare Data. Demography 2016, 53, 1109–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oza-Frank, R.; Narayan, K.V. Effect of length of residence on overweight by region of birth and age at arrival among US immigrants. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 13, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkimbeng, M.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Angel, J.L.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Thorpe, J.R.J.; Han, H.-R.; Winch, P.J.; Szanton, S.L. Longer Residence in the United States is Associated with More Physical Function Limitations in African Immigrant Older Adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkimbeng, M.; Turkson-Ocran, R.-A.; Thorpe, R.J.; Szanton, S.L.; Cudjoe, J.; Taylor, J.L.; Commodore-Mensah, Y. Prevalence of functional limitations among foreign and US-born Black older adults: 2010–2016 National Health Interview Surveys. Ethn. Health 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Population Reference Bureau. Elderly Immigrants in the United States—Population Reference Bureau. 2013. Available online: https://www.prb.org/us-elderly-immigrants/ (accessed on 9 January 2020).

- Close, C.; Kouvonen, A.; Bosqui, T.; Patel, K.; O’Reilly, D.; Donnelly, M. The mental health and wellbeing of first generation migrants: A systematic-narrative review of reviews. Glob. Health 2016, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenta, H.; Hyman, I.; Noh, S. Determinants of Depression Among Ethiopian Immigrants and Refugees in Toronto. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2004, 192, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekunov, J. Immigration and Risk of Psychiatric Disorders: A Review of Existing Literature. Am. J. Psychiatry Resid. J. 2016, 11, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkimbeng, M.; Nmezi, N.A.; Baker, Z.G.; Taylor, J.L.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Shippee, T.P.; Szanton, S.L.; Gaugler, J.E. Depressive Symptoms in Older African Immigrants with Mobility Limitations: A Descriptive Study. Clin. Gerontol. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Yi, S.S.; De La Cruz, N.L.; Trinh-Shevrin, C. Defining Ethnic Enclave and Its Associations with Self-Reported Health Outcomes Among Asian American Adults in New York City. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 19, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezuk, B.; Li, X.; Cederin, K.; Concha, J.; Kendler, K.S.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. Ethnic enclaves and risk of psychiatric disorders among first- and second-generation immigrants in Sweden. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Hu, W. Immigrant health, place effect and regional disparities in Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 98, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentry, D.M. Challenges of Elderly Immigrants. Hum. Serv. Today 2010, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, C. Addressing the Social Work Needs of Older Immigrants and Refugees. Available online: https://www.socialworktoday.com/news/enews_0911_01.shtml (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Farrel, C. For Many Boomer Immigrants, Rough Times Ahead. Next Avenue, 14 May 2014. Available online: https://www.nextavenue.org/many-boomer-immigrants-rough-times-ahead (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Gorospe, E. Elderly Immigrants: Emerging Challenge for the U.S. Healthcare System. Internet J. Healthc. Adm. 2005, 4, 1–14. Available online: https://ispub.com/IJHCA/4/1/13504 (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Kean, N. Older Immigrants’ Rough Road Map to Public Benefits. 2019. Available online: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/law_aging/publications/bifocal/vol-40/volume-40-issue-6/older-immigrants/ (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Li, J.; Xu, L.; Chi, I. Challenges and resilience related to aging in the United States among older Chinese immigrants. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 22, 1548–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiltz, T. Aging, Undocumented and Uninsured Immigrants Challenge Cities and States. 2018. Available online: http://pew.org/2lIzeNC (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Models of Human Development. In Readings on the Development of Children, 2nd ed.; NY Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention|Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Sallis, F.J.; Owen, N.; Fisher, E.B. Ecological Models of Health Behavior. In Health Behavior and Health Education Theory, Research, and Practice; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; p. 590. Available online: https://edc.iums.ac.ir/files/hshe-soh/files/beeduhe_0787996149.pdf#page=503 (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Kilanowski, J.F. Breadth of the socio-ecological model. J. Agromedicine 2017, 22, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, C.M.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Hui, S.L.; Perkins, A.J.; Hendrie, H.C. Six-Item Screener to Identify Cognitive Impairment Among Potential Subjects for Clinical Research. Med. Care 2002, 40, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey, 2010–2014. Public-Use Data File and Documentation 2015. Available online: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2014/srvydesc.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nkimbeng, M.; Taylor, J.L.; Roberts, L.; Winch, P.J.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Thorpe, R.J.; Han, H.-R.; Szanton, S.L. “All I know is that there is a lot of discrimination”: Older African immigrants’ experiences of discrimination in the United States. Geriatr. Nurs. 2020, 42, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tropp, L.R.; Erkut, S.; Coll, C.G.; Alarcón, O.; García, H.A.V. Psychological Acculturation: Development of A New Measure for Puerto Ricans on the U.S. Mainland. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1999, 59, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. Measuring Discrimination Resource. 2012. Available online: https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/davidrwilliams/files/measuring_discrimination_resource_feb_2012_0_0.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Williams, D.R.; Yu, Y.; Jackson, J.S.; Anderson, N.B. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Hannes, K.; Harden, A.; Noyes, J.; Harris, J.; Tong, A. COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies); Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ibe-Lamberts, K.; Tshiswaka, D.I.; Osideko, A.; Schwingel, A. Understanding Transnational African Migrants’ Perspectives of Dietary Behavior. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2016, 4, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiller, N.G.; Basch, L.; Blanc-Szanton, C. Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992, 645, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konadu-Agyemang, K.; Takyi, B. African Immigrants in the USA: Some Reflection on Their Pre-and Post-Migration Experiences. Arab. World Geogr. 2001, 4, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, T.Y. Transnationalism among African immigrants in North America: The case of Ghanaians in Canada. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2003, 4, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffoe, M. The Social Reconstruction of “Home” among African Immigrants in Canada. Can. Ethn. Stud. 2010, 41, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkson-Ocran, R.N.; Nmezi, N.A.; Botchway, M.O.; Szanton, S.L.; Golden, S.H.; Cooper, L.A.; Commodore-Mensah, Y. Comparison of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors Among African Immigrants and African Americans: An Analysis of the 2010 to 2016 National Health Interview Surveys. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2020, 9, e013220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, M.Y.; Thoreson, C.K.; Ricks, M.; Courville, A.B.; Thomas, F.; Yao, J.; Katzmarzyk, P.; Sumner, A.E. Worse Cardiometabolic Health in African Immigrant Men than African American Men: Reconsideration of the Healthy Immigrant Effect. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2014, 12, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health Systems in Africa: Community Perceptions and Perspectives. The World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa Brazzaville Republic of Congo. 2012. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/english---health_systems_in_africa---2012.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Granbom, M.; Himmelsbach, I.; Haak, M.; Löfqvist, C.; Oswald, F.; Iwarsson, S. Residential normalcy and environmental experiences of very old people: Changes in residential reasoning over time. J. Aging Stud. 2014, 29, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, N.; Dubé, R.; Després, C.; Freitas, A.; Légaré, F. Choosing between staying at home or moving: A systematic review of factors influencing housing decisions among frail older adults. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granbom, M.; Nkimbeng, M.; Roberts, L.C.; Gitlin, L.N.; Taylor, J.L.; Szanton, S.L. “So I am stuck, but it’s OK”: Residential reasoning and housing decision-making of low-income older adults with disabilities in Baltimore, Maryland. Hous. Soc. 2020, 48, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, C.; Ekerdt, D.J. Residential Reasoning and the Tug of the Fourth Age. Gerontologist 2017, 57, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfqvist, C.; Granbom, M.; Himmelsbach, I.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F.; Haak, M. Voices on Relocation and Aging in Place in Very Old Age--A Complex and Ambivalent Matter. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Global Network for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: Looking Back Over the Last Decade, Looking Forward to the Next; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/278979/WHO-FWC-ALC-18.4-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- World Health Organization. Measuring the Age-Friendliness of Cities: A Guide to Using Core Indicators; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/203830/1/9789241509695_eng.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Klok, J.; Van Tilburg, T.G.; Suanet, B.; Fokkema, T. Transnational aging among older Turkish and Moroccan migrants in the Netherlands: Determinants of transnational behavior and transnational belonging. Transnatl. Soc. Rev. 2017, 7, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.R. Space, time, and self: Rethinking aging in the contexts of immigration and transnationalism. J. Aging Stud. 2012, 26, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassar, L.; Wilding, R.; Boccagni, P.; Merla, L. Aging in place in a mobile world: New media and older people’s support networks. Transnatl. Soc. Rev. 2017, 7, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, V.; Schweppe, C. Transnational aging: Toward a transnational perspective in old age research. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pseudo Name | Sex | Age | Length of Stay | Marital Status | Country of Origin | Immigration Status | Level of Education | Employment Status | Household Income | Health Ins. | Acculturation (U.S Score) | Acculturation (CoO Score) | Discrimination Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Judith | Female | 64 | 30 | Widowed | Cameroon | Asylum seeker | Bachelor’s | Part-time | $20,000–$39,999 | No | 2.5 | 3 | 5 |

| Paul | Male | 60 | 4 | Married | Cameroon | Asylum seeker | HS/ GED | Part-time | Under $20,000 | No | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Janet | Female | 58 | 6 | Married | Cameroon | Permanent resident | Bachelor’s | Full-time | $20,000–$39,999 | Yes | 2.8 | 3.3 | 16 |

| John | Male | 61 | 22 | Married | Cameroon | Citizen | Master’s | Full-time | $80,000–$99,999 | Yes | 1.3 | 3.5 | 11 |

| Joshua | Male | 68 | 0 | Married | Cameroon | Asylum seeker | <HS | Retired | Don’t Know | No | 2.1 | 2.7 | 7 |

| Cletus | Male | 74 | 20 | Married | Cameroon | Permanent resident | Master’s | Retired | $40,0000–$59,999 | Yes | 0.7 | 4 | 14 |

| Veronica | Female | 68 | 28 | Widowed | Cameroon | Citizen | Bachelor’s | Retired | Under $20,000 | Yes | 2.3 | 3 | 4 |

| Mary | Female | 59 | 22 | Widowed | Ghana | Citizen | Associates | Full-time | $40,0000–$59,999 | Yes | 1.5 | 3 | 10 |

| Philip | Male | 62 | 14 | Married | Ghana | Visa holder | HS/GED | Seeking | Prefer not answer | No | 3.3 | 3.8 | 3 |

| Peter | Male | 62 | 17 | Married | Ghana | Citizen | Master’s | Full-time | $60,000–$79,000 | Yes | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| Gloria | Female | 72 | 37 | Widowed | Liberia | Citizen | No formal ed. | Retired | Don’t Know | Yes | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Magdalene | Female | 65 | 33 | Separated-Divorced | Liberia | Permanent resident | Master’s | Retired | $40,0000–$59,999 | Yes | 4 | 4 | 22 |

| Felicia | Female | 65 | 3 | Married | Nigeria | Permanent resident | Bachelor’s | Part-time | Under $20,000 | Yes | 1.7 | 3.8 | 7 |

| Rose | Female | 61 | 13 | Separated-Divorced | Sierra Leone | Citizen | Masters | Full-time | $40,0000–$59,999 | Yes | 3 | 3.17 | 3 |

| Laura | Female | 52 | 28 | Widowed | Sierra Leone | Citizen | Master’s | Part-time | $80,000–$99,999 | No | 2.5 | 4 | 23 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nkimbeng, M.; Akumbom, A.; Granbom, M.; Szanton, S.L.; Shippee, T.P.; Thorpe, R.J., Jr.; Gaugler, J.E. Where to Retire? Experiences of Older African Immigrants in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031040

Nkimbeng M, Akumbom A, Granbom M, Szanton SL, Shippee TP, Thorpe RJ Jr., Gaugler JE. Where to Retire? Experiences of Older African Immigrants in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031040

Chicago/Turabian StyleNkimbeng, Manka, Alvine Akumbom, Marianne Granbom, Sarah L. Szanton, Tetyana P. Shippee, Roland J. Thorpe, Jr., and Joseph E. Gaugler. 2022. "Where to Retire? Experiences of Older African Immigrants in the United States" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031040

APA StyleNkimbeng, M., Akumbom, A., Granbom, M., Szanton, S. L., Shippee, T. P., Thorpe, R. J., Jr., & Gaugler, J. E. (2022). Where to Retire? Experiences of Older African Immigrants in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031040