Division of Labour and Parental Mental Health and Relationship Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic-Mandated Homeschooling

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Economic Theory—Specialisation

1.2. Psychological Theory—Equity

1.3. Homeschooling and Division of Labour

1.4. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Sample Size Justification

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographics

2.3.2. Workload Division Measure

2.3.3. Emotional Well-Being

2.3.4. Relationship Well-Being

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

3.2. Effect of Specialisation and Equity (H1 and H2)

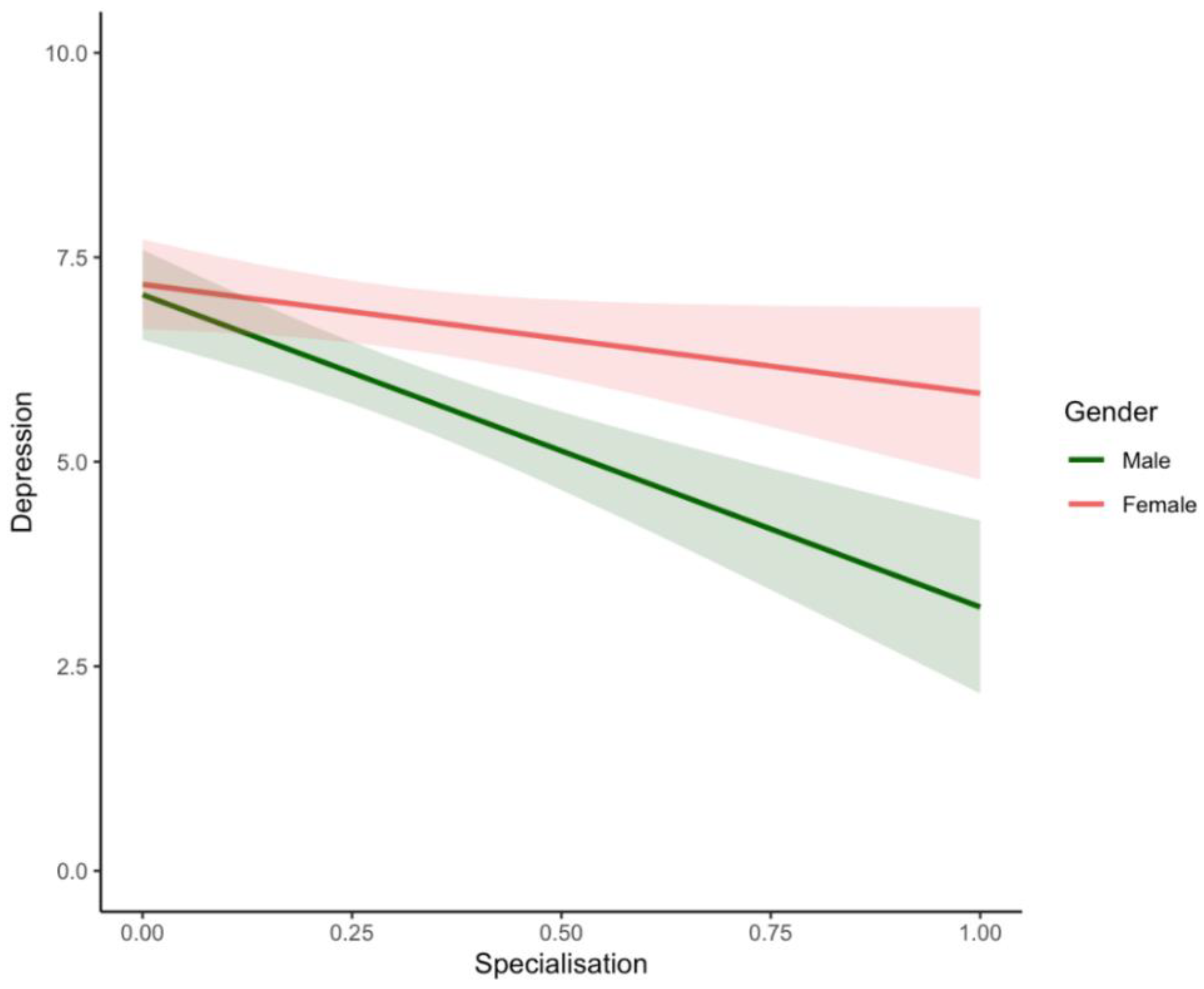

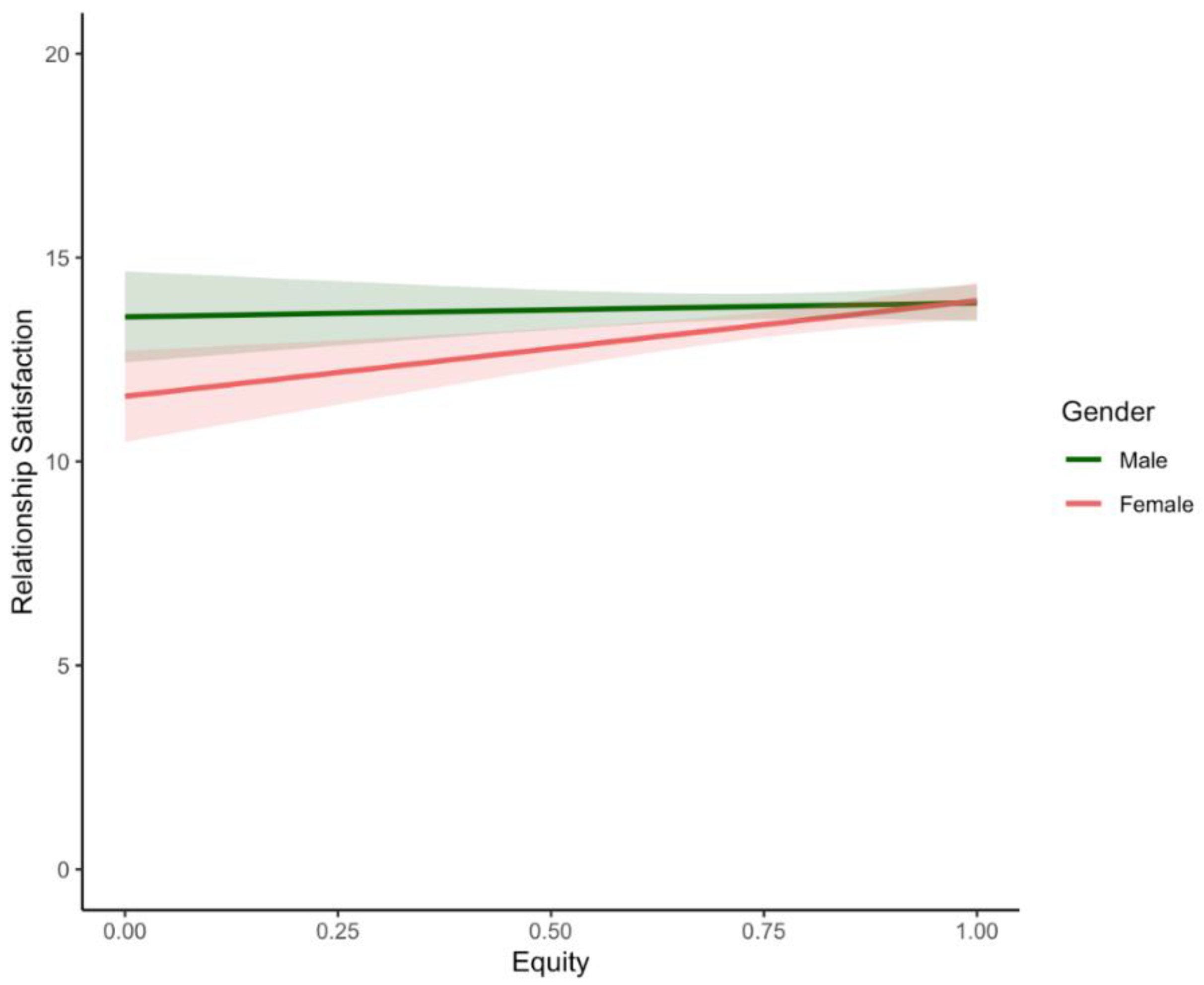

3.3. Gender Differences in Specialisation and Equity (H3 and H4)

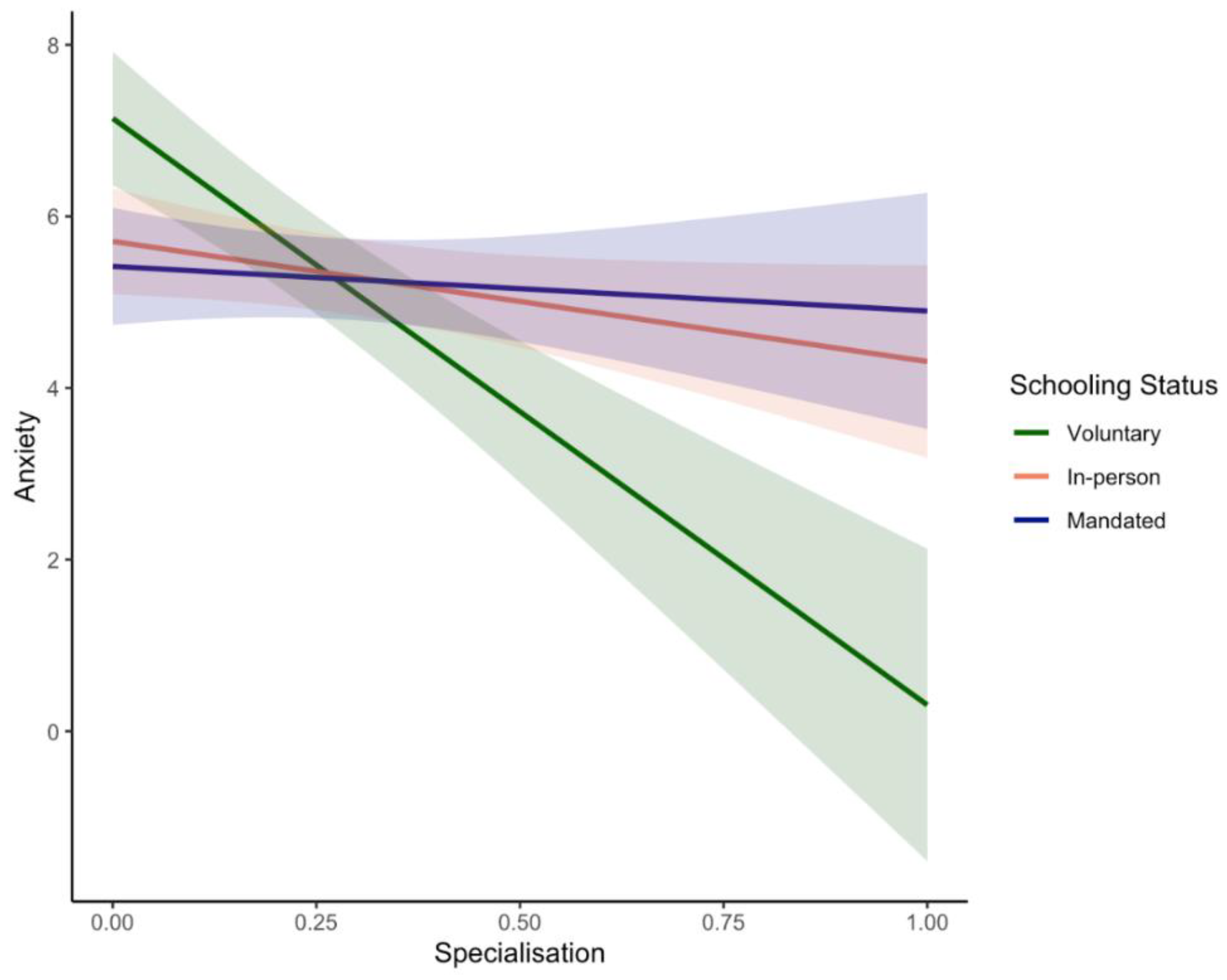

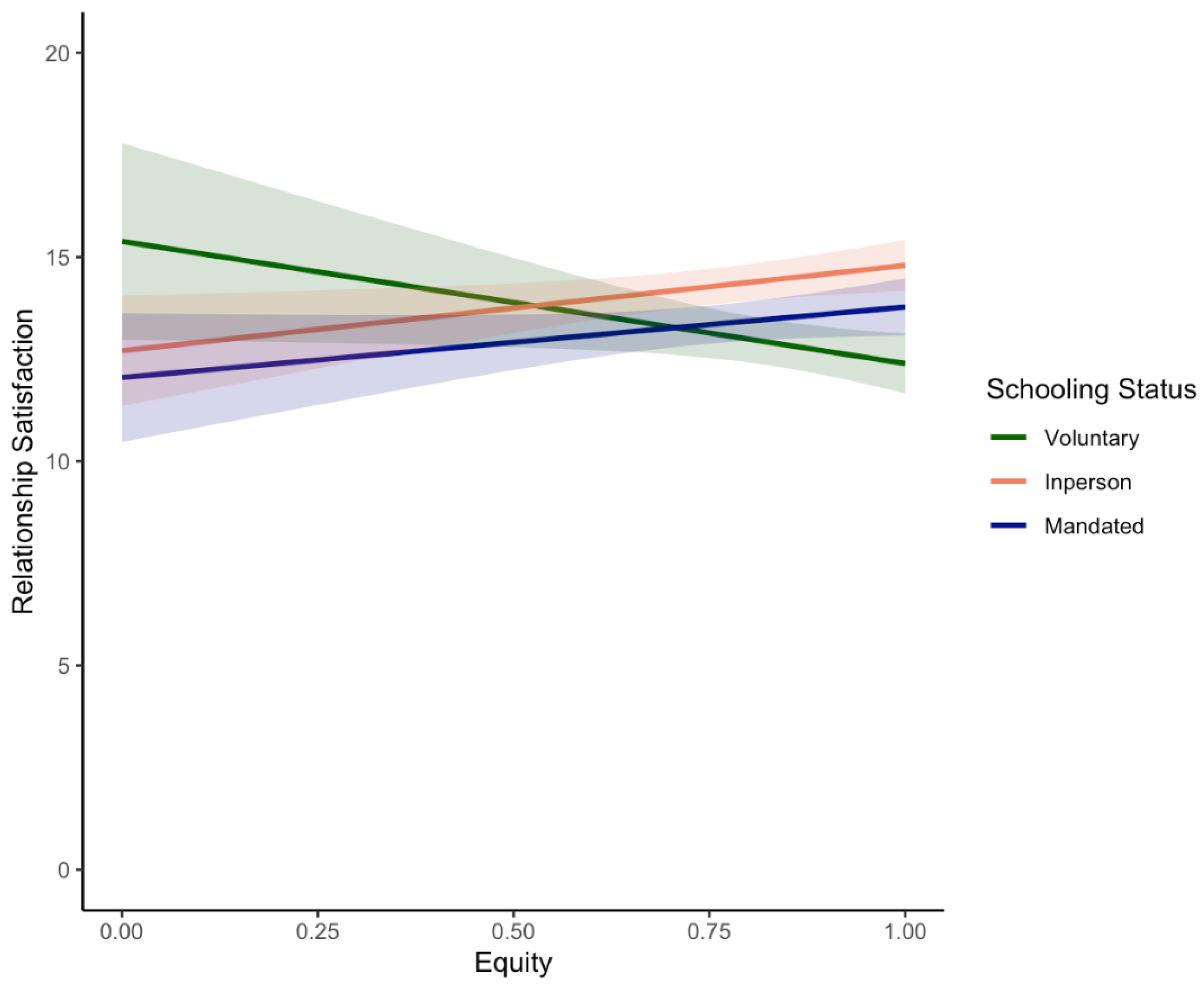

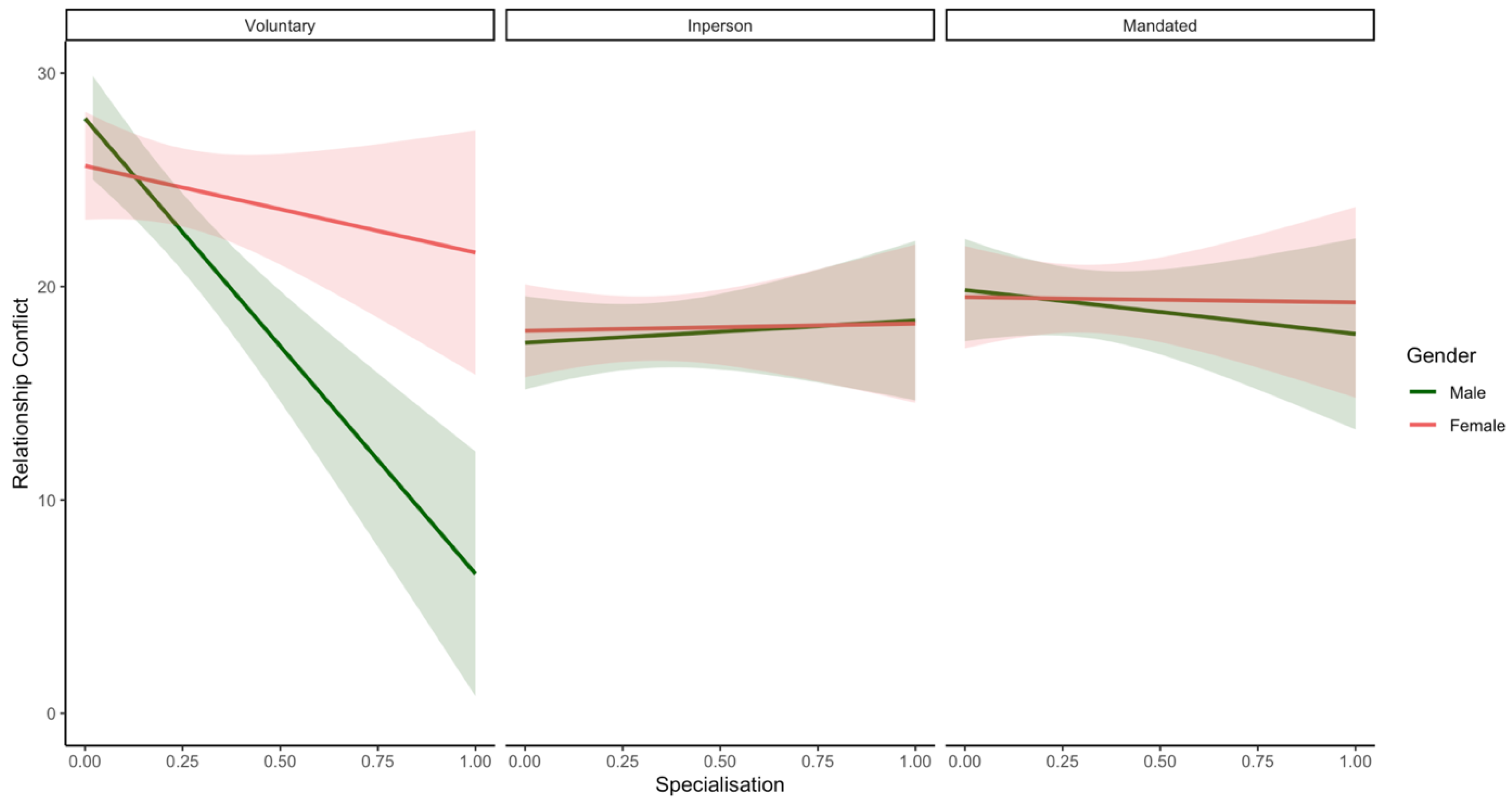

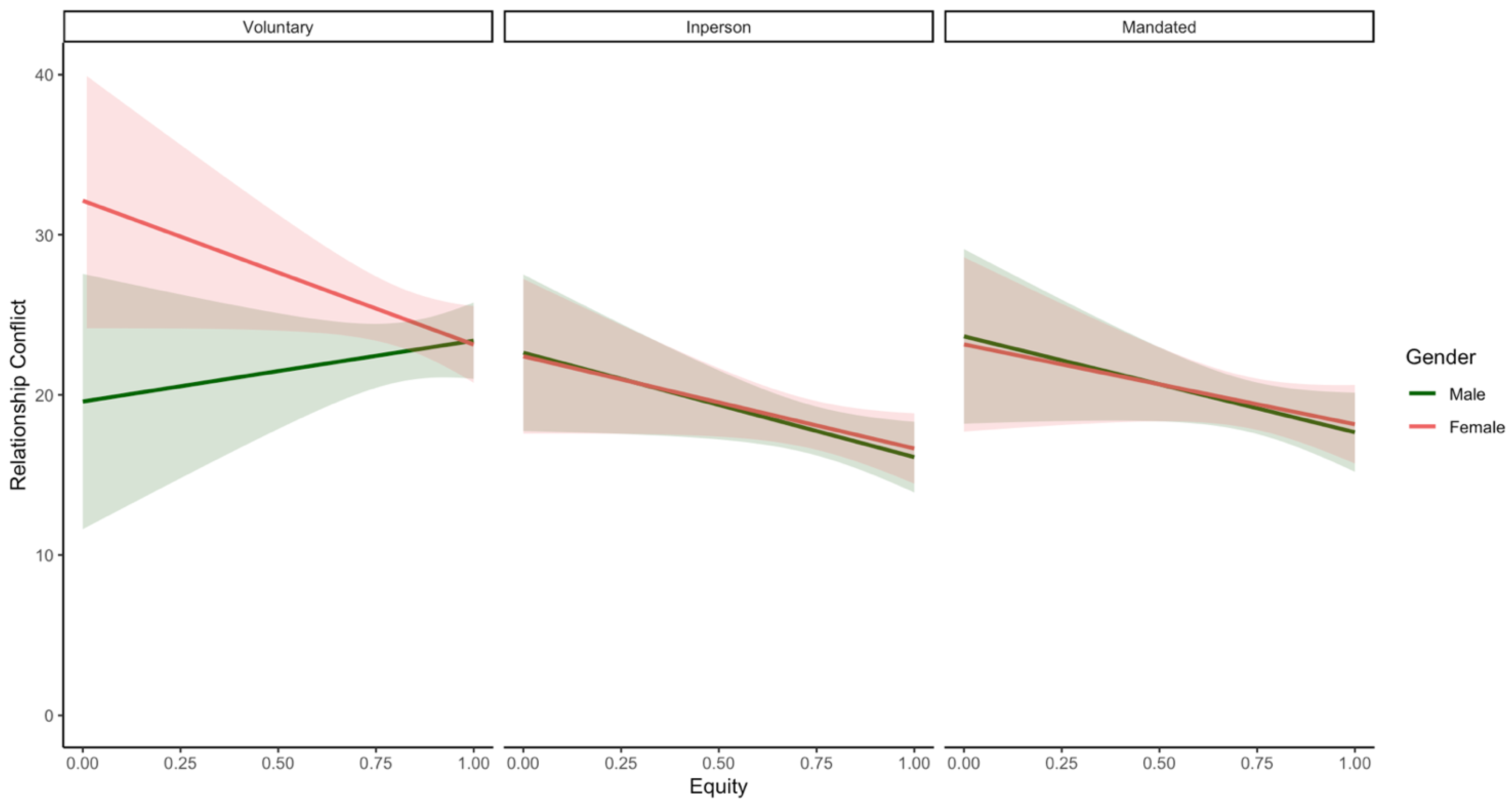

3.4. Differences by Homeschooling Status (H5)

3.5. Supplementary Analyses

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Viner, R.M.; Russell, S.J.; Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Ward, J.; Stansfield, C.; Mytton, O.; Bonell, C.; Booy, R. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: A rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; McBride, O.; Murphy, J.; Miller, J.G.; Hartman, T.K.; Levita, L.; Mason, L.; Martinez, A.P.; McKay, R.; Stocks, T.V.A.; et al. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and COVID-19-related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenham, C.; Smith, J.; Morgan, R. Gender and COVID-19 Working Group. COVID-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 2020, 395, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.M.; Litt, D.M.; Stewart, S.H. Drinking to cope with the pandemic: The unique associations of COVID-19-related perceived threat and psychological distress to drinking behaviors in American men and women. Addict. Behav. 2020, 110, 106532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, F.; Van Wijngaarden-Cremers, P.J.M. Women’s Mental Health in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2020, 1, 588372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschke, K.; Arnaud, N.; Austermann, M.I.; Thomasius, R. Risk factors for prospective increase in psychological stress during COVID-19 lockdown in a representative sample of adolescents and their parents. BJPsych Open 2021, 7, e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Warren, N.; McMahon, L.; Dalais, C.; Henry, I.; Siskind, D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 369, m1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newkirk, K.; Perry-Jenkins, M.; Sayer, A.G. Division of Household and Childcare Labor and Relationship Conflict among Low-Income New Parents. Sex Roles 2016, 76, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, N.; Kraaykamp, G.; Verbakel, E. Couples’ Division of Employment and Household Chores and Relationship Satisfaction: A Test of the Specialization and Equity Hypotheses. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 33, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Mohtadi, H. Labor Specialization and Endogenous Growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 1992, 82, 404–408. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, A.; Guterman, O. Homeschooling Is Not Just about Education: Focuses of Meaning. J. Sch. Choice 2017, 11, 148–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, S.H.; Rodriguez, L.M.; Elgendi, M.; King, F.E.; Nogueira-Arjona, R.; Sherry, S.B.; Stewart, S.H. Parenting through a pandemic: Mental health and substance use consequences of mandated homeschooling. Couple Fam. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2021, 10, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, K.; Scheibling, C.; Milkie, M.A. The Division of Domestic Labor before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada: Stagnation versus Shifts in Fathers’ Contributions. Can. Rev. Sociol. Can. de Sociol. 2020, 57, 523–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.L.; Petts, R.; Pepin, J. Men and Women Agree: During the COVID-19 Pandemic Men Are Doing More at Home; Council on Contemporary Families: Austin, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, L.; Churchill, B. Dual-earner Parent Couples’ Work and Care during COVID-19. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021, 28, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. A Treatise on the Family; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; ISBN 0674020669. [Google Scholar]

- Brines, J. Economic Dependency, Gender, and the Division of Labor at Home. Am. J. Sociol. 1994, 100, 652–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S. The Relation Between Inequity and Emotions in Close Relationships. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1986, 49, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S. Equity and Social Exchange in Dating Couples: Associations with Satisfaction, Commitment, and Stability. J. Marriage Fam. 2001, 63, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barstad, A. Equality Is Bliss? Relationship Quality and the Gender Division of Household Labor. J. Fam. Issues 2014, 35, 972–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.L.; Miller, A.J.; Sassler, S.; Hanson, S. The Gendered Division of Housework and Couples’ Sexual Relationships: A Reexamination. J. Marriage Fam. 2016, 78, 975–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.L.; Miller, A.J.; Sassler, S. Stalled for Whom? Change in the Division of Particular Housework Tasks and Their Consequences for Middle-to Low-Income Couples. Socius Sociol. Res. Dyn. World 2018, 4, 2378023118765867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaris, A.; Longmore, M.A. Ideology, Power, and Equity: Testing Competing Explanations for the Perception of Fairness in Household Labor. Soc. Forces 1996, 74, 1043–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.N.C.; Cooper, C.L. The transition to parenthood in dual-earner couples. Psychol. Med. 1988, 18, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmijn, M.; Monden, C.W. The division of labor and depressive symptoms at the couple level. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2011, 29, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, P.; Farkas, G. Households, Employment, and Gender: A Social, Economic, and Demographic View, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Lippe, T.; Jager, A.; Kops, Y. Combination Pressure. Acta Sociol. 2006, 49, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W. Dual-Earner Couples in the United States. Encycl. Fam. Stud. 2016, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offer, S. The Costs of Thinking about Work and Family: Mental Labor, Work–Family Spillover, and Gender Inequality among Parents in Dual-earner Families. Sociol. Forum 2014, 29, 916–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, M.; Loeve, A.; Manting, D. Income dynamics in couples and the dissolution of marriage and cohabitation. Demography 2007, 44, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinengo, G.; Jacob, J.I.; Hill, E.J. Gender and the Work-Family Interface: Exploring Differences across the Family Life Course. J. Fam. Issues 2010, 31, 1363–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J.; Jacob, J.I.; Shannon, L.L.; Brennan, R.T.; Blanchard, V.L.; Martinengo, G. Exploring the relationship of workplace flexibility, gender, and life stage to family-to-work conflict, and stress and burnout. Community Work. Fam. 2008, 11, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.; Duxbury, L.; Lee, C. Impact of Life-Cycle Stage and Gender on the Ability to Balance Work and Family Responsibilities. Fam. Relat. 1994, 43, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R.; Russell, M.; Cooper, M.L. Relation of work-family conflict to health outcomes: A four-year longitudinal study of employed parents. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1997, 70, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duffy, J.F.; De Castillero, E.R. Do sleep disturbances mediate the association between work-family conflict and depressive symptoms among nurses? A cross-sectional study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 24, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.A.; Duxbury, L.E.; Irving, R.H. Work-family conflict in the dual-career family. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1992, 51, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barling, J.; Macewen, K.E. Linking work experiences to facets of marital functioning. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blossfeld, H.-P.; Müller, R. Union Disruption in Comparative Perspective: The Role of Assortative Partner Choice and Careers of Couples. Int. J. Sociol. 2002, 32, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manting, D.; Loeve, J.A. Economic Circumstances and Union Dissolution of Couples in the 1990s in The Netherlands; Statistics Netherlands Voorburg/Heerlen: Voorburg, Heerlen, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Poortman, A.-R.; Kalmijn, M. Women’s Labour Market Position and Divorce in the Netherlands: Evaluating Economic Interpretations of the Work Effect. Eur. J. Popul. 2002, 18, 175–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, V.K. Women’s Employment and the Gain to Marriage: The Specialization and Trading Model. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1997, 23, 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, R.; Astone, N.M.; Kim, Y.J.; Rothert, K.; Standish, N.J. Women’s Employment, Marital Happiness, and Divorce. Soc. Forces 2002, 81, 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minello, A. The pandemic and the female academic. Nature 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerer, L.; Medina, J. When Mom’s Zoom Meeting Is the One That Has to Wait. New York Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/us/politics/women-coronavirus-2020.html (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Waddell, N.; Overall, N.C.; Chang, V.T.; Hammond, M.D. Gendered division of labor during a nationwide COVID-19 lockdown: Implications for relationship problems and satisfaction. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2021, 38, 1759–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, L.; Bünning, M. Parenthood as a driver of increased gender inequality during COVID-19? Exploratory evidence from Germany. Eur. Soc. 2020, 23, S658–S673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Lippe, T.; Treas, J.; Norbutas, L. Unemployment and the Division of Housework in Europe. Work. Employ. Soc. 2017, 32, 650–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, C.; Kirchmaier, I.; Trautmann, S.T. Marriage, parenthood and social network: Subjective well-being and mental health in old age. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helbig, S.; Lampert, T.; Klose, M.; Jacobi, F. Is Parenthood Associated with Mental Health? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalucza, S.; Hammarström, A.; Nilsson, K. Mental health and parenthood—A longitudinal study of the relationship between self-reported mental health and parenthood. Health Sociol. Rev. 2015, 24, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbo, N.; Arpino, B. The Role of Family Orientations in Shaping the Effect of Fertility on Subjective Well-being: A Propensity Score Matching Approach. Demography 2016, 53, 955–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.E.; Diener, E.; Georgellis, Y.; Lucas, R. Lags and Leads in Life Satisfaction: A Test of the Baseline Hypothesis. Econ. J. 2008, 118, F222–F243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijters, P.; Johnston, D.W.; Shields, M.A. Life Satisfaction Dynamics with Quarterly Life Event Data. Scand. J. Econ. 2011, 113, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, H.-P.; Behrman, J.R.; Skytthe, A. Partner + Children = Happiness? An Assessment of the Effect of Fertility and Partnerships on Subjective Well-Being in Danish Twins. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2005, 31, 407–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollmann-Schult, M. Parenthood and Life Satisfaction: Why Don’t Children Make People Happy? J. Marriage Fam. 2014, 76, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Group [UNSDG]. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women; UNSDG: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Taulbut, M.; McKee, M.; McCartney, G. Mitigating the wider health effects of COVID-19 pandemic response. BMJ 2020, 369, m1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meuwly, N.; Wilhelm, P.; Eicher, V.; Perrez, M. Welchen Einfluss Hat Die Aufteilung von Hausarbeit Und Kinderbetreuung Auf Partnerschaftskonflikte Und Partnerschaftszufriedenheit Bei Berufstätigen Paaren? [Division of Housework and Child Care, Conflict, and Relationship Satisfaction in Dual-Earner Coup. Z. Für Fam. 2011, 23, 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, D.P.; Kiger, G.; Mannon, S.E. Domestic Labor and Marital Satisfaction: How Much or How Satisfied? Marriage Fam. Rev. 2005, 37, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.K.; La Valley, A.G.; Farinelli, L. The experience and expression of anger, guilt, and sadness in marriage: An equity theory explanation. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2008, 25, 699–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Thibodeau, R.; Jorgensen, R.S. Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 68–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppanner, L.; Brandén, M.; Turunen, J. Does Unequal Housework Lead to Divorce? Evidence from Sweden. Sociology 2017, 52, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieman, S.; Ruppanner, L.; Milkie, M.A. Who Helps with Homework? Parenting Inequality and Relationship Quality Among Employed Mothers and Fathers. Day Care Early Educ. 2017, 39, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Newton, T.L. Marriage and Health: His and Hers. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 472–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaske, S. For the Family? How Class and Gender Shape Womens Work; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 0199912041. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, P. Love between Equals: How Peer Marriage Really Works; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 1439105219. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.H. Superdads: How fathers balance work and family in the twenty-first century. J. Gend. Stud. 2014, 23, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellert, P.; Häusler, A.; Suhr, R.; Gholami, M.; Rapp, M.; Kuhlmey, A.; Nordheim, J. Testing the stress-buffering hypothesis of social support in couples coping with early-stage dementia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaris, A. The role of relationship inequity in marital disruption. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2007, 24, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisco, M.L.; Williams, K. Perceived Housework Equity, Marital Happiness, and Divorce in Dual-Earner Households. J. Fam. Issues 2003, 24, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaris, A. The 20-year trajectory of marital quality in enduring marriages: Does equity matter? J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2010, 27, 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavee, Y.; Katz, R. Divison of Labor, Perceived Fairness, and Marital Quality: The Effect of Gender Ideology. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, C.E. Gender, Household Labor, and Psychological Distress: The Impact of the Amount and Division of Housework. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1999, 40, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.E.; Perry-Jenkins, M. Division of Labor and Working-Class Women’s Well-Being Across the Transition to Parenthood. J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harryson, L.; Novo, M.; Hammarström, A. Is gender inequality in the domestic sphere associated with psychological distress among women and men? Results from the Northern Swedish Cohort. J. Epidemiol. Community Heal. 2010, 66, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomaguchi, K.M.; Milkie, M.A. Costs and Rewards of Children: The Effects of Becoming a Parent on Adults’ Lives. J. Marriage Fam. 2003, 65, 356–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riina, E.M.; Feinberg, M.E. Involvement in Childrearing and Mothers’ and Fathers’ Adjustment. Fam. Relat. 2012, 61, 836–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, R.C.; Sherwood, A.; Matthews, K.A.; Blumenthal, J.A. Household Responsibilities, Income, and Ambulatory Blood Pressure among Working Men and Women. Psychosom. Med. 2011, 73, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lively, K.J.; Steelman, L.C.; Powell, B. Equity, Emotion, and Household Division of Labor Response. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2010, 73, 358–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, A.; Smith, S. Baby Steps: The Gender Division of Childcare during the COVID-19 Pandemic; IZA Working Paper Series; ISER: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, S.M.; Milkie, M.A.; Sayer, L.C.; Robinson, J.P. Is Anyone Doing the Housework? Trends in the Gender Division of Household Labor. Soc. Forces 2000, 79, 191–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.M.; Sayer, L.C.; Milkie, M.A.; Robinson, J.P. Housework: Who Did, Does or Will Do It, and How Much Does It Matter? Soc. Forces 2012, 91, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizavi, S.S.; Sofer, C. The Division of Labour within the Household: Is There Any Escape from Traditional Gender Roles? 2008; unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, R.M.; Johnson, M.D.; Galambos, N.L.; Krahn, H.J. Time, Money, or Gender? Predictors of the Division of Household Labour across Life Stages. Sex Roles 2017, 78, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.L.; Petts, R.J.; Pepin, J.R. Flexplace Work and Partnered Fathers’ Time in Housework and Childcare. Men Masculinities 2021, 24, 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedulla, D.S.; Thébaud, S. Can We Finish the Revolution? Gender, Work-Family Ideals, and Institutional Constraint. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 80, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré, L.; González, L. Does paternity leave reduce fertility? J. Public Econ. 2019, 172, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. Women at the Core of the Fight against COVID-19 Crisis; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tamm, M. Fathers’ parental leave-taking, childcare involvement and labor market participation. Labour Econ. 2019, 59, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesRoches, D.; Deacon, S.; Rodriguez, L.; Sherry, S.; Nogueira-Arjona, R.; Elgendi, M.; Meier, S.; Abbass, A.; King, F.; Stewart, S. Homeschooling during COVID-19: Gender Differences in Work–Family Conflict and Alcohol Use Behaviour among Romantic Couples. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.; Allan, S. Fundamental Elements in a Child’s Right to Education: A Study of Home Education Research and Regulation in Australia. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2010, 2, 350–366. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, S.A. The Home Schooling Mother-Teacher: Toward a Theory of Social Integration. Peabody J. Educ. 2000, 75, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, M. Home Education: Constructions of Choice. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2010, 3, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, M.L. Kingdom of Children: Culture and Controversy in the Homeschooling Movement; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E.E. Motherhood, homeschooling, and mental health. Sociol. Compass 2019, 13, e12725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois, J. The Temporal Emotion Work of Motherhood: Homeschoolers’ Strategies for Managing Time Shortage. Gend. Soc. 2010, 24, 421–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois, J. Home Is Where the School Is: The Logic of Homeschooling and the Emotional Labor of Mothering; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 0814789439. [Google Scholar]

- Sherfinski, M.; Chesanko, M. Disturbing the data: Looking into gender and family size matters with US Evangelical homeschoolers. Gend. Place Cult. 2014, 23, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.S.; Sheran, M.E. Homeschooling in the United States: Revelation or Revolution? Unpubl. Work. Pap. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Furness, A. Helping Homeschoolers in the Library; American Library Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, L.G. Homeschooling Education. Educ. Urban Soc. 2011, 44, 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, R.A.; Kenny, D.A. APIMPowerR: An Interactive Tool for Actor-Partner Interdependence Model Power Analysis. Comput. Softw. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fleury, M.-J.; Grenier, G.; Bamvita, J.-M.; Perreault, M.; Caron, J. Typology of adults diagnosed with mental disorders based on socio-demographics and clinical and service use characteristics. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plass-Christl, A.; Haller, A.-C.; Otto, C.; Barkmann, C.; Wiegand-Grefe, S.; Hölling, H.; Schulte-Markwort, M.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Klasen, F. Parents with mental health problems and their children in a German population based sample: Results of the BELLA study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, K.M.; Edlund, M.J.; Larson, S. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Mental Health Problems and Use of Mental Health Care. Med. Care 2005, 43, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, O.; Alfons, V. Do Demographics Affect Marital Satisfaction? J. Sex Marital Ther. 2007, 33, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainah, Z.; Nasir, R.; Hashim, R.S.; Yusof, N. Effects of Demographic Variables on Marital Satisfaction. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. General Social Survey on Time Use. Available online: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Instr.pl?Function=assembleInstr&lang=en&Item_Id=217656 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and Standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the General Population. Med. Care 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010, 32, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, F.; Bérard, A.; Sheehy, O.; Huneau, M.-C.; Briggs, G.; Chambers, C.; Einarson, A.; Johnson, D.; Kao, K.; Koren, G.; et al. Reliability and validity of the 4-item perceived stress scale among pregnant women: Results from the OTIS antidepressants study. Res. Nurs. Health 2012, 35, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warttig, S.L.; Forshaw, M.J.; South, J.; White, A. New, normative, English-sample data for the Short Form Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4). J. Health. Psychol. 2013, 18, 1617–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewenthal, K.M.; Lewis, C.A. An Introduction to Psychological Tests and Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.L.; Griffin, D.W.; Rose, P.; Bellavia, G.M. Calibrating the sociometer: The relational contingencies of self-esteem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackinnon, S.P.; Sherry, S.B.; Antony, M.M.; Stewart, S.H.; Sherry, D.L.; Hartling, N. Caught in a bad romance: Perfectionism, conflict, and depression in romantic relationships. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 26, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, J.L.; Rogge, R.D. Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.M.; Diebels, K.J.; Barnow, Z.B. The reliability of relationship satisfaction: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2011, 25, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M. robustlmm: An R Package for Robust Estimation of Linear Mixed-Effects Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 75, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P.; Wilcox, R.R. Robust statistical methods: A primer for clinical psychology and experimental psychopathology researchers. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 98, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, M.A.; Vallejo-Slocker, L.; Fernández-Abascal, E.G.; Mañanes, G. Determining Factors for Stress Perception Assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) in Spanish and Other European Samples. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.O.; Peri-Okonny, P.; Gosch, K.; Thomas, M.; Mena, C.; Hiatt, W.R.; Jones, P.G.; Provance, J.B.; Labrosciano, C.; Jelani, Q.-U.; et al. Association of Perceived Stress Levels With Long-term Mortality in Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e208741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.U.; Ulvenes, P.G.; Øktedalen, T.; Hoffart, A. Psychometric Properties of the General Anxiety Disorder 7-Item (GAD-7) Scale in a Heterogeneous Psychiatric Sample. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambe, L.; Mackinnon, S.P.; Stewart, S.H. Dyadic conflict, drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems: A psychometric study and longitudinal actor–partner interdependence model. J. Fam. Psychol. 2015, 29, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S.; Gonzaga, G.C.; Ogburn, E.L.; VanderWeele, T.J. Marital satisfaction and break-ups differ across on-line and off-line meeting venues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 10135–10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, J. The Joys and Justice of Housework. Sociology 2000, 34, 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Lewin-Epstein, N.; Stier, H.; Baumgärtner, M.K. Perceived Equity in the Gendered Division of Household Labor. J. Marriage Fam. 2008, 70, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Wallace, J.E.; Polachek, A.J. Gender Differences in Perceived Domestic Task Equity. J. Fam. Issues 2013, 36, 1751–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.; Zimmerman, D.H. Doing Gender. Gend. Soc. 1987, 1, 125–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltrane, S. Research on Household Labor: Modeling and Measuring the Social Embeddedness of Routine Family Work. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 1208–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Houser, D. When are women willing to lead? The effect of team gender composition and gendered tasks. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 101340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killewald, A.; Gough, M. Does Specialization Explain Marriage Penalties and Premiums? Am. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 78, 477–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, E.; Hanson, L.L.M.; Westerlund, H.; Theorell, T.; Brenner, M.H. Depressive symptoms as a cause and effect of job loss in men and women: Evidence in the context of organisational downsizing from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gili, M.; López-Navarro, E.; Castro, A. Gender differences in mental health during the economic crisis. Psicothema 2016, 28, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poortman, A.-R. How Work Affects Divorce. J. Fam. Issues 2005, 26, 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, R.; Kimmel, J. If You’re Happy and You Know It: How Do Mothers and Fathers in the US Really Feel about Caring for Their Children? Fem. Econ. 2014, 21, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, J.L.; Nelson, S.K.; River, L.M.; Birken, S.A.; Moss-Racusin, C. Gender Differences in Work-Family Guilt in Parents of Young Children. Sex Roles 2016, 76, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendén, M.G.; Klysing, A.; Lindqvist, A.; Renström, E.A. The (Not So) Changing Man: Dynamic Gender Stereotypes in Sweden. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesley, N. What Does It Mean to Be a “Breadwinner” Mother? J. Fam. Issues 2016, 38, 2594–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huinink, J.; Reichart, E. Der Weg in Die Traditionelle Arbeitsteilung – Eine Einbahnstraße? The Path to the Traditional Division of Work: A One Way Road? In Familiale Beziehungen, Familienalltag und Soziale Netzwerke: Family Relationships, Everyday Life, and Social Networks; Bien, W., Marbach, J.H., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 43–80. ISBN 978-3-531-91980-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, P.D.S.; De Araújo, T.M. Associação entre sobrecarga doméstica e transtornos mentais comuns em mulheres. Rev. Bras. de Epidemiologia 2012, 15, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciciolla, L.; Luthar, S.S. Invisible Household Labor and Ramifications for Adjustment: Mothers as Captains of Households. Sex Roles 2019, 81, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; Overall, N.C. Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples’ relationships. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, D.G.; Simpson, J.N.; Beers, N.S. Returning to School in the Era of COVID-19. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 1028–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, G.R.; A Smith, J.; García, C.; A Garcia, M.; A Thomas, P. Exacerbating Inequalities: Social Networks, Racial/Ethnic Disparities, and the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 76, e88–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.B.; McHale, S.M.; Crouter, A.C. The Division of Household Labor: Longitudinal Changes and Within-Couple Variation. J. Marriage Fam. 2012, 74, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Income Survey. 2019. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210323/dq210323a-eng.htm (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Statistics Canada. Ethnic and Cultural Origins of Canadians: Portrait of a Rich Heritage. 2017. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016016/98-200-x2016016-eng.cfm (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Semega, J.; Kollar, M.; Shrider, E.A.; Creamer, J. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2019. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-270.html (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Statistics Canada. Census in Brief: Portrait of Children’s Family Life in Canada in 2016; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017; Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016006/98-200-x2016006-eng.cfm (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Goldberg, A.E.; Smith, J.Z.; Perry-Jenkins, M. The Division of Labor in Lesbian, Gay, and Heterosexual New Adoptive Parents. J. Marriage Fam. 2012, 74, 812–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, R.; Sun, W.; Huang, W.; Liang, D.; Tang, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, D.; et al. The Effects of Online Homeschooling on Children, Parents, and Teachers of Grades 1–9 During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e925591-e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.L.; Seibert, S.E.; Goering, D.; O’Boyle, E.H. A Tale of Two Sample Sources: Do Results from Online Panel Data and Conventional Data Converge? J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, L.; Allin, S.; Marchildon, G.; Burke, S.; Barry, S.; Siersbaek, R.; Thomas, S.; Rajan, S.; Koval, A.; Alexander, M.; et al. A comparison of 2020 health policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. Health Policy 2021, 126, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, O.; Neuman, A. Emotion, behaviour, and the structuring of home education in Israel: The role of routine. Aust. Educ. Res. 2020, 48, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, O.; Neuman, A. Personality, socio-economic status and education: Factors that contribute to the degree of structure in homeschooling. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2017, 21, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, O.; Neuman, A. Parental attachment and internalizing and externalizing problems of Israeli school-goers and homeschoolers. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 35, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Disrupting Mental Health Services in Most Countries. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-10-2020-covid-19-disrupting-mental-health-services-in-most-countries-who-survey (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Schulz, M.S.; Cowan, C.P.; Cowan, P.A. Promoting healthy beginnings: A randomized controlled trial of a preventive intervention to preserve marital quality during the transition to parenthood. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | In-Person Learners (n = 772) | Mandated Homeschoolers (n = 664) | Voluntary Homeschoolers (n = 488) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age—M (SD) *** | 39.13 (6.70) | 38.70 (6.91) | 36.17 (5.61) |

| Number of children—M (SD) *** | 2.10 (0.85) | 1.97 (0.85) | 1.48 (0.88) |

| Average child age—M (SD) † | 8.64 (2.75) | 8.80 (2.86) | 8.44 (2.03) |

| Relationship length (yrs)—M (SD) *** | 13.63 (6.24) | 13.05 (6.19) | 10.64 (5.05) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 388 | 334 | 242 |

| Female | 383 | 328 | 244 |

| Other/ Prefer not to answer | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Relationship Status *** | |||

| Mixed gender | 642 | 562 | 458 |

| Same gender | 128 | 98 | 26 |

| Other/Prefer not to answer | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Family Income *** | |||

| CAD 25,000 or less per year | 36 | 33 | 8 |

| Between CAD 26,000 and 50,000 | 78 | 76 | 83 |

| Between CAD 51,000 and 75,000 | 98 | 110 | 160 |

| Between CAD 76,000 and 100,000 | 172 | 106 | 122 |

| Between CAD 101,000 and 125,000 | 110 | 84 | 60 |

| Between CAD 126,000 and 150,000 | 117 | 94 | 38 |

| CAD 151,000 or more per year | 128 | 132 | 10 |

| Prefer not to answer | 33 | 29 | 7 |

| Highest Level of Education *** | |||

| Some high school | 17 | 15 | 10 |

| High school graduate | 81 | 74 | 44 |

| Some college/university | 88 | 67 | 130 |

| College/university graduate | 414 | 301 | 214 |

| Some post-graduate | 41 | 34 | 57 |

| Post-graduate degree | 131 | 173 | 33 |

| Employment *** | |||

| Employed (Full/Part time) | 634 | 529 | 389 |

| Unemployed | 116 | 129 | 89 |

| Student (Full/Part time) | 21 | 4 | 1 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| Ethnicity *** | |||

| White | 552 | 438 | 416 |

| Asian or Arab/West Asian 1 | 131 | 126 | 23 |

| Latin American or Black or First Nations 1 | 52 | 60 | 37 |

| Multiracial | 25 | 28 | 6 |

| Other/Unknown | 12 | 12 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | In-Person Learners—Mean (SD) | Mandated HS— Mean (SD) | Voluntary HS— Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.83 ** | 0.56 ** | −0.42 ** | 0.52 ** | −0.08 † | −0.06 | 6.19 (5.96) | 6.29 (5.61) | 7.41 (5.65) | |

| 0.86 ** | 0.58 ** | −0.42 ** | 0.50 ** | −0.07 | −0.03 | 5.05 (5.11) | 5.24 (4.96) | 5.88 (4.78) | |

| 0.51 ** | 0.53 ** | −0.46 ** | 0.39 ** | −0.08 † | −0.02 | 6.32 (2.87) | 6.41 (3.10) | 7.10 (2.46) | |

| −0.36 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.40 ** | −0.55 ** | 0.07 | −0.06 | 14.45 (4.48) | 13.39 (4.79) | 12.64 (4.27) | |

| 0.55 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.38 ** | −0.51 ** | −0.07 | −0.03 | 19.36 (14.07) | 19.22 (13.46) | 24.26 (15.38) | |

| 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05 † | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.18 ** | 0.74 (0.25) | 0.75 (0.23) | 0.84 (0.19) | |

| −0.14 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.06 * | 0.01 | −0.12 ** | −0.33 ** | 0.29 (0.30) | 0.28 (0.26) | 0.22 (0.24) | |

| Mean (Total sample) | 6.54 | 5.33 | 6.55 | 13.62 | 20.55 | 0.77 | 0.27 | |||

| SD (Total sample) | 5.78 | 4.98 | 2.87 | 4.59 | 14.37 | 0.23 | 0.27 |

| Outcome | Predictors | B | SE (b) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.044/0.622 AIC/BIC = 11,303/11,353 | Intercept | 10.46 ** | 1.21 | 8.08–12.83 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.12–0.00 | 0.068 | |

| No. of children | −0.48 † | 0.2 | −0.87–−0.09 | 0.015 | |

| Relationship length | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.11–0.03 | 0.253 | |

| Family Income | −0.07 | 0.1 | −0.26–0.12 | 0.470 | |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.20–0.22 | 0.927 | |

| Specialisation | −2.91 ** | 0.62 | −4.12–−1.69 | <0.001 | |

| Anxiety Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.036/0.544 AIC/BIC = 10,882/10,932 | Intercept | 8.60 ** | 1.03 | 6.57–10.62 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.10–0.01 | 0.106 | |

| No. of children | −0.34† | 0.17 | −0.66–−0.01 | 0.043 | |

| Relationship length | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.10–0.01 | 0.135 | |

| Family Income | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.17–0.15 | 0.878 | |

| Education | −0.07 | 0.1 | −0.26–0.12 | 0.497 | |

| Specialisation | −2.20 ** | 0.52 | −3.22–−1.17 | <0.001 | |

| Perceived Stress Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.030/0.495 AIC/BIC = 8878.0/8927.8 | Intercept | 9.22 ** | 0.59 | 8.07–10.36 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 * | 0.02 | −0.07–−0.01 | 0.007 | |

| No. of children | −0.17 | 0.09 | −0.35–0.02 | 0.076 | |

| Relationship length | −0.001 | 0.02 | −0.03–0.03 | 0.935 | |

| Family Income | −0.14 * | 0.05 | −0.23–−0.05 | 0.003 | |

| Education | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.14–0.08 | 0.559 | |

| Specialisation | −0.68 † | 0.3 | −1.26–−0.10 | 0.022 | |

| Relationship Satisfaction Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.026/0.779 AIC/BIC = 10,054/10,103 | Intercept | 12.49 ** | 0.99 | 10.54–14.43 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08–0.03 | 0.362 | |

| No. of children | 0.76 ** | 0.17 | 0.44–1.08 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship length | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02–0.10 | 0.200 | |

| Family Income | 0.04 | 0.08 | −0.11–0.19 | 0.625 | |

| Education | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.16–0.14 | 0.901 | |

| Specialisation | 0.02 | 0.52 | −1.01–1.04 | 0.972 | |

| Relationship Conflict Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.043/0.703 AIC/BIC = 14,513/14,562 | Intercept | 30.33 ** | 3.06 | 24.34–36.33 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.15 | 0.08 | −0.31–0.01 | 0.058 | |

| No. of children | −1.58 * | 0.5 | −2.57–−0.59 | 0.002 | |

| Relationship length | −0.15 | 0.09 | −0.33–0.03 | 0.094 | |

| Family Income | 0.36 | 0.24 | −0.11–0.83 | 0.138 | |

| Education | −0.08 | 0.26 | −0.58–0.42 | 0.749 | |

| Specialisation | −5.07 * | 1.59 | −8.19–−1.96 | 0.001 |

| Outcome | Predictors | B | SE (b) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.026/0.622 AIC/BIC =11,324/11,374.2 | Intercept | 10.98 ** | 1.22 | 8.59–13.37 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.12–0.00 | 0.055 | |

| No. of children | −0.65 * | 0.2 | −1.04–−0.26 | 0.001 | |

| Relationship Length | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.12–0.02 | 0.153 | |

| Family Income | −0.05 | 0.1 | −0.24–0.14 | 0.602 | |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.21–0.22 | 0.961 | |

| Equity | −0.34 | 0.74 | −1.79–1.10 | 0.642 | |

| Anxiety Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.022/0.544 AIC/BIC =10,899/10,949.0 | Intercept | 8.99 ** | 1.04 | 6.96–11.02 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.10–0.01 | 0.090 | |

| No. of children | −0.45 * | 0.17 | −0.78–−0.12 | 0.007 | |

| Relationship Length | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11–0.01 | 0.082 | |

| Family Income | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.17–0.16 | 0.941 | |

| Education | −0.07 | 0.1 | −0.26–0.12 | 0.469 | |

| Equity | 0.12 | 0.62 | −1.10–1.34 | 0.848 | |

| Perceived Stress Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.029/0.495 AIC/BIC = 8880/8929.7 | Intercept | 9.34 ** | 0.58 | 8.19–10.48 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 * | 0.02 | −0.07–−0.01 | 0.006 | |

| No. of children | −0.23 † | 0.09 | −0.41–−0.04 | 0.015 | |

| Relationship Length | 0.001 | 0.02 | −0.04–0.03 | 0.789 | |

| Family Income | −0.12 * | 0.05 | −0.22–−0.03 | 0.009 | |

| Education | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.14–0.08 | 0.571 | |

| Equity | −0.63 | 0.35 | −1.31–0.05 | 0.070 | |

| Relationship Satisfaction Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.027/0.779 AIC/BIC = 10,052/10,101.7 | Intercept | 12.47 ** | 0.98 | 10.54–14.40 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08–0.03 | 0.369 | |

| No. of children | 0.79 ** | 0.17 | 0.47–1.12 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship Length | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02–0.10 | 0.189 | |

| Family Income | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.13–0.17 | 0.760 | |

| Education | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.16–0.13 | 0.879 | |

| Equity | 0.77 | 0.61 | −0.43–1.97 | 0.208 | |

| Relationship Conflict Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.034/0.703 AIC/BIC = 14,523/14,572.4 | Intercept | 31.25 ** | 3.06 | 25.25–37.24 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.16 | 0.08 | −0.32–−0.00 | 0.050 | |

| No. of children | −1.88 ** | 0.5 | −2.87–−0.90 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship Length | −0.17 | 0.09 | −0.35–0.01 | 0.061 | |

| Family Income | 0.39 | 0.24 | −0.09–0.87 | 0.107 | |

| Education | −0.09 | 0.26 | −0.59–0.41 | 0.732 | |

| Equity | −0.94 | 1.87 | −4.61–2.73 | 0.616 |

| Outcome | Predictors | B | SE (b) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.054/0.598 AIC/BIC = 9669.8/9729.0 | Intercept | 10.39 ** | 1.24 | 7.96–12.81 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11–0.01 | 0.127 | |

| No. of children | −0.52 * | 0.2 | −0.91–−0.14 | 0.008 | |

| Relationship length | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.11–0.03 | 0.283 | |

| Family Income | −0.12 | 0.1 | −0.31–0.07 | 0.229 | |

| Education | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.24–0.20 | 0.873 | |

| Specialisation | −2.58 ** | 0.63 | −3.81–−1.34 | <0.001 | |

| Gender | 0.40 ** | 0.09 | 0.22–0.57 | <0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Gender | 1.24 ** | 0.32 | 0.62–1.87 | <0.001 | |

| Anxiety Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.050/0.532 AIC/BIC = 9345.8/9405.0 | Intercept | 8.62 ** | 1.07 | 6.51–10.72 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.09–0.02 | 0.166 | |

| No. of children | −0.4 † | 0.17 | −0.74–−0.07 | 0.018 | |

| Relationship length | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.10–0.02 | 0.199 | |

| Family Income | −0.04 | 0.09 | −0.21–0.13 | 0.614 | |

| Education | −0.07 | 0.1 | −0.27–0.13 | 0.468 | |

| Specialisation | −2.12 ** | 0.54 | −3.19–−1.06 | <0.001 | |

| Gender | 0.45 ** | 0.08 | 0.28–0.61 | <0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Gender | 0.87 * | 0.3 | 0.27–1.46 | 0.004 | |

| Perceived Stress Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.047/0.512 AIC/BIC = 7708.7/7767.8 | Intercept | 9.52 ** | 0.64 | 8.26–10.77 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 * | 0.02 | −0.08–−0.01 | 0.008 | |

| No. of children | −0.19 | 0.1 | −0.39–0.01 | 0.057 | |

| Relationship length | 0.001 | 0.02 | −0.04–0.04 | 0.982 | |

| Family Income | −0.16 * | 0.05 | −0.26–−0.06 | 0.001 | |

| Education | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.17–0.07 | 0.430 | |

| Specialisation | −0.55 | 0.32 | −1.18–0.09 | 0.090 | |

| Gender | 0.27 ** | 0.05 | 0.17–0.37 | <0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Gender | 0.56 * | 0.18 | 0.20–0.92 | 0.002 | |

| Relationship Satisfaction Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.033/0.788 AIC/BIC = 8646.9/8706.1 | Intercept | 12.57 ** | 1.05 | 10.50–14.64 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08–0.03 | 0.426 | |

| No. of children | 0.82 ** | 0.17 | 0.48–1.16 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship length | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.03–0.10 | 0.236 | |

| Family Income | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.14–0.18 | 0.811 | |

| Education | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.19–0.11 | 0.599 | |

| Specialisation | −0.26 | 0.56 | −1.35–0.83 | 0.641 | |

| Gender | −0.19 ** | 0.05 | −0.29–−0.09 | <0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Gender | −0.64 ** | 0.19 | −1.02–−0.27 | 0.001 | |

| Relationship Conflict Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.043/0.667 AIC/BIC = 12,483.8/12,543.0 | Intercept | 30.08 ** | 3.12 | 23.96–36.19 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.28–0.04 | 0.156 | |

| No. of children | −1.76 ** | 0.5 | −2.74–−0.77 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship length | −0.18 | 0.09 | −0.36–0.01 | 0.059 | |

| Family Income | 0.19 | 0.25 | −0.30–0.67 | 0.445 | |

| Education | −0.15 | 0.27 | −0.67–0.38 | 0.584 | |

| Specialisation | −3.26 † | 1.61 | −6.41–−0.11 | 0.042 | |

| Gender | 0.3 | 0.2 | −0.09–0.70 | 0.129 | |

| Specialisation × Gender | 1.91 * | 0.72 | 0.49–3.32 | 0.008 |

| Outcome | Predictors | B | SE (b) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.039/0.593 AIC/BIC = 9693.5/9752.7 | Intercept | 10.97 ** | 1.24 | 8.54–13.40 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.12–0.01 | 0.101 | |

| No. of children | −0.73 ** | 0.2 | −1.12–−0.34 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship length | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.12–0.03 | 0.210 | |

| Family Income | −0.08 | 0.1 | −0.28–0.11 | 0.411 | |

| Education | −0.05 | 0.11 | −0.27–0.17 | 0.675 | |

| Equity | −1.04 | 0.77 | −2.55–0.47 | 0.177 | |

| Gender | 0.42 ** | 0.09 | 0.25–0.60 | <0.001 | |

| Equity × Gender | −0.96 † | 0.39 | −1.72–−0.19 | 0.014 | |

| Anxiety Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.036/0.531 AIC/BIC = 9363.3/9422.5 | Intercept | 9.07 ** | 1.08 | 6.96–11.19 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.10–0.01 | 0.140 | |

| No. of children | −0.55 * | 0.17 | −0.88–−0.21 | 0.001 | |

| Relationship length | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11–0.02 | 0.144 | |

| Family Income | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.20–0.15 | 0.760 | |

| Education | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.30–0.10 | 0.346 | |

| Equity | −0.28 | 0.67 | −1.59–1.02 | 0.670 | |

| Gender | 0.46 ** | 0.08 | 0.30–0.63 | <0.001 | |

| Equity × Gender | −0.88 † | 0.37 | −1.60–−0.16 | 0.017 | |

| Perceived Stress Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.045/0.508 AIC/BIC = 7714.6/7773.8 | Intercept | 9.66 ** | 0.64 | 8.42–10.91 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.05 * | 0.02 | −0.08–−0.01 | 0.006 | |

| No. of children | −0.26 † | 0.1 | −0.45–−0.06 | 0.010 | |

| Relationship length | 0.001 | 0.02 | −0.04–0.03 | 0.925 | |

| Family Income | −0.14 * | 0.05 | −0.25–−0.04 | 0.005 | |

| Education | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.18–0.06 | 0.355 | |

| Equity | −0.71 | 0.39 | −1.48–0.06 | 0.069 | |

| Gender | 0.28 ** | 0.05 | 0.18–0.38 | <0.001 | |

| Equity × Gender | −0.37 | 0.22 | −0.81–0.07 | 0.099 | |

| Relationship Satisfaction Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.038/0.789 AIC/BIC =8635.5/ 8694.7 | Intercept | 12.45 ** | 1.05 | 10.40–14.50 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08–0.03 | 0.459 | |

| No. of children | 0.87 ** | 0.17 | 0.53–1.21 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship length | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.03–0.10 | 0.253 | |

| Family Income | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.17–0.15 | 0.859 | |

| Education | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.17–0.13 | 0.830 | |

| Equity | 1.34 † | 0.67 | 0.03–2.66 | 0.046 | |

| Gender | −0.20 ** | 0.05 | −0.31–−0.10 | <0.001 | |

| Equity × Gender | 1.00 ** | 0.23 | 0.55–1.46 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship Conflict Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.041/0.664 AIC/BIC = 12,491.6/ 12,550.8 | Intercept | 30.86 ** | 3.11 | 24.77–36.96 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.29–0.04 | 0.133 | |

| No. of children | −2.10 ** | 0.5 | −3.09–−1.12 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship length | −0.18 † | 0.09 | −0.37–−0.00 | 0.048 | |

| Family Income | 0.27 | 0.25 | −0.22–0.76 | 0.278 | |

| Education | −0.18 | 0.27 | −0.70–0.34 | 0.501 | |

| Equity | −3.21 | 1.95 | −7.04–0.62 | 0.100 | |

| Gender | 0.34 | 0.2 | −0.05–0.73 | 0.089 | |

| Equity × Gender | −0.65 | 0.88 | −2.38–1.07 | 0.458 |

| Outcome | Predictors | B | SE (b) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.054/0.623 AIC/BIC = 11,291.4/11,363.2 | Intercept | 10.20 ** | 1.38 | 7.49–12.91 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11–0.01 | 0.116 | |

| No. of children | −0.37 | 0.2 | −0.77–0.03 | 0.069 | |

| Relationship Length | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.11–0.03 | 0.240 | |

| Family Income | −0.08 | 0.1 | −0.27–0.11 | 0.433 | |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.11 | −0.18–0.25 | 0.760 | |

| Specialisation | −12.33 ** | 3.53 | −19.26–−5.41 | <0.001 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.01 | 0.24 | −0.47–0.46 | 0.979 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.18 | 0.27 | −0.72–0.36 | 0.511 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 1 | 1.11 | 0.83 | −0.52–2.73 | 0.182 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 2 | 3.32 * | 1.02 | 1.33–5.32 | 0.001 | |

| Anxiety Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.053/0.546 AIC/BIC = 10,866.6/10,938.4 | Intercept | 7.99 ** | 1.17 | 5.70–10.28 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.09–0.02 | 0.183 | |

| No. of children | −0.24 | 0.17 | −0.57–0.10 | 0.169 | |

| Relationship Length | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11–0.01 | 0.112 | |

| Family Income | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.20–0.13 | 0.686 | |

| Education | −0.04 | 0.1 | −0.23–0.15 | 0.648 | |

| Specialisation | −13.79 ** | 2.97 | −19.61–−7.97 | <0.001 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | 0.03 | 0.2 | −0.36–0.42 | 0.885 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | 0.003 | 0.23 | −0.45–0.45 | 0.989 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 1 | 1.52 † | 0.7 | 0.15–2.88 | 0.029 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 2 | 3.92 ** | 0.85 | 2.24–5.59 | <0.001 | |

| Perceived Stress Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.034/0.496 AIC/BIC = 8879.1/8951.0 | Intercept | 9.61 ** | 0.67 | 8.30–10.92 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 † | 0.02 | −0.07–−0.01 | 0.012 | |

| No. of children | −0.12 | 0.1 | −0.31–0.07 | 0.210 | |

| Relationship Length | −0.000 | 0.02 | −0.03–0.03 | 10.000 | |

| Family Income | −0.13 * | 0.05 | −0.22–−0.03 | 0.008 | |

| Education | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.13–0.09 | 0.683 | |

| Specialisation | −0.88 | 1.69 | −4.19–2.43 | 0.603 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.09 | 0.11 | −0.31–0.13 | 0.436 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.25 | 0.13 | −0.51–0.00 | 0.052 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 1 | −0.11 | 0.4 | −0.89–0.66 | 0.776 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 2 | 0.22 | 0.49 | −0.73–1.17 | 0.651 | |

| Relationship Satisfaction Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.049/0.780 AIC/BIC = 10,036.6/10,108.4 | Intercept | 10.93 ** | 1.13 | 8.71–13.15 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.09–0.02 | 0.173 | |

| No. of children | 0.57 ** | 0.17 | 0.24–0.90 | 0.001 | |

| Relationship Length | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02–0.09 | 0.226 | |

| Family Income | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.13–0.17 | 0.815 | |

| Education | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.16–0.13 | 0.832 | |

| Specialisation | 8.42 * | 2.95 | 2.64–14.20 | 0.004 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | 0.73 ** | 0.2 | 0.34–1.11 | <0.001 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | 0.51 † | 0.23 | 0.07–0.96 | 0.024 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 1 | −1.18 | 0.69 | −2.53–0.18 | 0.088 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 2 | −2.80 ** | 0.85 | −4.46–−1.13 | 0.001 | |

| Relationship Conflict Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.060/0.704 AIC/BIC = 14,498.5/14,570.4 | Intercept | 33.55 ** | 3.49 | 26.71–40.39 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.28–0.04 | 0.139 | |

| No. of children | −1.05† | 0.52 | −2.07–−0.04 | 0.042 | |

| Relationship Length | −0.14 | 0.09 | −0.32–0.03 | 0.114 | |

| Family Income | 0.46 | 0.24 | −0.02–0.93 | 0.060 | |

| Education | −0.01 | 0.26 | −0.50–0.50 | 0.995 | |

| Specialisation | −21.41 † | 8.99 | −39.04–−3.78 | 0.017 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.86 | 0.6 | −2.04–0.32 | 0.153 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −2.29 ** | 0.7 | −3.66–−0.93 | 0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 1 | 1.27 | 2.11 | −2.87–5.40 | 0.548 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 2 | 6.52† | 2.59 | 1.44–11.59 | 0.012 |

| Outcome | Predictors | B | SE (b) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.029/0.623 AIC/BIC = 11,328.5/11,400.3 | Intercept | 11.23 ** | 1.42 | 8.44–14.02 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.12–0.01 | 0.078 | |

| No. of children | −0.59 * | 0.2 | −0.99–−0.19 | 0.004 | |

| Relationship Length | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.12–0.02 | 0.184 | |

| Family Income | −0.02 | 0.1 | −0.22–0.17 | 0.815 | |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.11 | −0.19–0.24 | 0.815 | |

| Equity | 0.33 | 4.45 | −8.39–9.06 | 0.941 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.06 | 0.24 | −0.54–0.41 | 0.792 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.33 | 0.29 | −0.89–0.23 | 0.248 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 1 | 0.58 | 1.01 | −1.39–2.56 | 0.561 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 2 | −0.97 | 1.28 | −3.48–1.54 | 0.449 | |

| Anxiety Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.025/0.546 AIC/BIC = 10,903.5/10,975.3 | Intercept | 8.78 ** | 1.21 | 6.41–11.14 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.10–0.01 | 0.116 | |

| No. of children | −0.42 † | 0.17 | −0.75–−0.08 | 0.016 | |

| Relationship Length | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11–0.01 | 0.102 | |

| Family Income | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.16–0.17 | 0.955 | |

| Education | −0.06 | 0.1 | −0.25–0.14 | 0.574 | |

| Equity | 3.01 | 3.75 | −4.34–10.35 | 0.422 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | 0 | 0.2 | −0.40–0.40 | 0.988 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.09 | 0.24 | −0.56–0.39 | 0.723 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 1 | 0.14 | 0.85 | −1.52–1.80 | 0.871 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 2 | −1.5 | 1.08 | −3.61–0.61 | 0.164 | |

| Perceived Stress Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.035/0.496 AIC/BIC = 8879.9/8951.7 | Intercept | 9.71 ** | 0.68 | 8.38–11.04 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 † | 0.02 | −0.07–−0.01 | 0.013 | |

| No. of children | −0.17 | 0.1 | −0.36–0.02 | 0.083 | |

| Relationship Length | 0.001 | 0.02 | −0.04–0.03 | 0.896 | |

| Family Income | −0.1 † | 0.05 | −0.20–−0.01 | 0.033 | |

| Education | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.13–0.09 | 0.735 | |

| Equity | 1.96 | 2.09 | −2.14–6.06 | 0.350 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.12 | 0.11 | −0.34–0.11 | 0.310 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.29 † | 0.13 | −0.56–−0.03 | 0.030 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 1 | −0.5 | 0.47 | −1.43–0.43 | 0.290 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 2 | −0.77 | 0.6 | −1.95–0.41 | 0.199 | |

| Relationship Satisfaction Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.051/0.780 AIC/BIC = 10,033.7/10,105.5 | Intercept | 11.06 ** | 1.15 | 8.81–13.31 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.09–0.02 | 0.185 | |

| No. of children | 0.61 ** | 0.17 | 0.28–0.94 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship Length | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.03–0.09 | 0.301 | |

| Family Income | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.17–0.14 | 0.841 | |

| Education | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.16–0.13 | 0.818 | |

| Equity | −9.89 * | 3.65 | −17.05–−2.73 | 0.007 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | 0.72 ** | 0.2 | 0.33–1.11 | <0.001 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | 0.51 † | 0.23 | 0.05–0.97 | 0.029 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 1 | 1.81 † | 0.83 | 0.20–3.43 | 0.028 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 2 | 3.27 * | 1.05 | 1.21–5.33 | 0.002 | |

| Relationship Conflict Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.048/0.704 AIC/BIC = 14,514.7/14,586.5 | Intercept | 35.69 ** | 3.56 | 28.71–42.68 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.29–0.03 | 0.106 | |

| No. of children | −1.47 * | 0.52 | −2.48–−0.46 | 0.004 | |

| Relationship Length | −0.15 | 0.09 | −0.33–0.02 | 0.089 | |

| Family Income | 0.58 † | 0.25 | 0.10–1.07 | 0.019 | |

| Education | −0.01 | 0.26 | −0.51–0.49 | 0.967 | |

| Equity | −2.45 | 11.24 | −24.47–19.57 | 0.827 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −1.03 | 0.61 | −2.23–0.17 | 0.091 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −2.69 ** | 0.72 | −4.10–−1.27 | <0.001 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 1 | 1.33 | 2.54 | −3.64–6.31 | 0.599 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 2 | −1.21 | 3.23 | −7.55–5.12 | 0.707 |

| Outcome | Predictors | B | SE (b) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.078/0.601 AIC/BIC = 9655.9/9758.1 | Intercept | 11.55 *** | 1.32 | 8.97–14.13 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.10–−0.00 | 0.050 | |

| No. of children | −0.31 | 0.2 | −0.70–0.09 | 0.125 | |

| Relationship length | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.00–0.00 | 0.433 | |

| Family Income | −0.11 | 0.1 | −0.31–0.08 | 0.247 | |

| Education | −0.001 | 0.11 | −0.22–0.22 | 0.969 | |

| Specialisation | −16.43 *** | 3.44 | −23.18–−9.69 | <0.001 | |

| Gender | −0.55 | 0.46 | −1.46–0.35 | 0.232 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.46 | 0.24 | −0.93–0.02 | 0.060 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.61 † | 0.27 | −1.15–−0.08 | 0.024 | |

| Gender × Specialisation | 0.28 | 1.77 | −3.19–3.75 | 0.876 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 1 | 0.23 | 0.12 | −0.01–0.47 | 0.060 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 0.23 | 0.13 | −0.03–0.49 | 0.081 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 1 | 2.34 ** | 0.83 | 0.71–3.97 | 0.005 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 2 | 4.21 *** | 0.99 | 2.27–6.15 | <0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −0.04 | 0.43 | −0.89–0.81 | 0.935 | |

| Specialisation × Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 0.46 | 0.51 | −0.54–1.46 | 0.369 | |

| Anxiety Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.077/0.538 AIC/BIC = 9324.5/9426.7 | Intercept | 9.01 *** | 1.14 | 6.77–11.25 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.05 † | 0.02 | −0.09–−0.00 | 0.036 | |

| No. of children | −0.28 | 0.17 | −0.61–0.06 | 0.109 | |

| Relationship length | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.00–0.00 | 0.569 | |

| Family Income | −0.07 | 0.09 | −0.24–0.10 | 0.418 | |

| Education | −0.07 | 0.1 | −0.27–0.13 | 0.482 | |

| Specialisation | −16.18 *** | 2.96 | −21.98–−10.37 | <0.001 | |

| Gender | −0.87 † | 0.44 | −1.73–−0.01 | 0.047 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.22 | 0.21 | −0.63–0.18 | 0.282 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.18 | 0.23 | −0.63–0.28 | 0.454 | |

| Gender × Specialisation | −0.48 | 1.67 | −3.76–2.80 | 0.773 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 1 | 0.31 ** | 0.12 | 0.08–0.53 | 0.008 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 0.33 ** | 0.13 | 0.09–0.58 | 0.008 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 1 | 2.34 ** | 0.72 | 0.93–3.74 | 0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 2 | 4.29 *** | 0.85 | 2.62–5.95 | <0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Gender × Homeschooling 1 | 0.11 | 0.41 | −0.69–0.92 | 0.782 | |

| Specialisation × Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 0.48 | 0.48 | −0.47–1.42 | 0.327 | |

| Perceived Stress Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.052/0.515 AIC/BIC = 7715.8/7818.0 | Intercept | 9.93 *** | 0.69 | 8.58–11.27 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 ** | 0.01 | −0.07–−0.01 | 0.003 | |

| No. of children | −0.13 | 0.1 | −0.33–0.08 | 0.219 | |

| Relationship length | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.00–0.00 | 0.390 | |

| Family Income | −0.15 ** | 0.05 | −0.25–−0.04 | 0.005 | |

| Education | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.16–0.08 | 0.520 | |

| Specialisation | −1.26 | 1.78 | −4.74–2.23 | 0.480 | |

| Gender | 0.10 | 0.27 | −0.42–0.62 | 0.708 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.11 | 0.13 | −0.35–0.14 | 0.382 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.29 † | 0.14 | −0.57–−0.01 | 0.039 | |

| Gender × Specialisation | 1.63 | 1.02 | −0.38–3.63 | 0.112 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 1 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.11–0.17 | 0.676 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.10–0.20 | 0.476 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 1 | 0.06 | 0.43 | −0.79–0.90 | 0.897 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 2 | 0.29 | 0.51 | −0.71–1.30 | 0.564 | |

| Specialisation × Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −0.43 | 0.25 | −0.92–0.06 | 0.087 | |

| Specialisation × Gender × Homeschooling 2 | −0.08 | 0.3 | −0.66–0.50 | 0.786 | |

| Relationship Satisfaction Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.061/0.789 AIC/BIC = 8631.5/8733.7 | Intercept | 10.49 *** | 1.13 | 8.28–12.71 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.06–0.03 | 0.415 | |

| No. of children | 0.62 *** | 0.18 | 0.27–0.97 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship length | −0.002 | 0.001 | −0.00–0.00 | 0.192 | |

| Family Income | 0.00 | 0.08 | −0.16–0.16 | 0.979 | |

| Education | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.19–0.12 | 0.649 | |

| Specialisation | 8.69 ** | 3.04 | 2.74–14.64 | 0.004 | |

| Gender | 0.40 | 0.28 | −0.14–0.95 | 0.144 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | 0.77 *** | 0.21 | 0.36–1.19 | <0.001 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | 0.66 ** | 0.24 | 0.19–1.13 | 0.006 | |

| Gender × Specialisation | 0.43 | 1.06 | −1.64–2.50 | 0.683 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −0.14 | 0.07 | −0.29–0.00 | 0.051 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 2 | −0.14 | 0.08 | −0.30–0.01 | 0.068 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 1 | −1.27 | 0.73 | −2.71–0.17 | 0.084 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 2 | −2.98 ** | 0.87 | −4.69–−1.27 | 0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −0.15 | 0.26 | −0.65–0.36 | 0.570 | |

| Specialisation × Gender × Homeschooling 2 | −0.34 | 0.31 | −0.94–0.26 | 0.267 | |

| Relationship Conflict Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.083/0.679 AIC/BIC = 12,435.3/12,537.5 | Intercept | 37.55 *** | 3.31 | 31.05–44.04 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.14 † | 0.07 | −0.27–−0.01 | 0.038 | |

| No. of children | −1.01 † | 0.51 | −2.01–−0.01 | 0.047 | |

| Relationship length | 0.002 | 0.004 | −0.01–0.01 | 0.592 | |

| Family Income | 0.29 | 0.25 | −0.20–0.77 | 0.243 | |

| Education | −0.02 | 0.26 | −0.54–0.50 | 0.945 | |

| Specialisation | −30.63 *** | 8.75 | −47.77–−13.49 | <0.001 | |

| Gender | 2.56 † | 1.03 | 0.54–4.58 | 0.013 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −2.40 *** | 0.61 | −3.61–−1.20 | <0.001 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −3.24 *** | 0.69 | −4.59–−1.89 | <0.001 | |

| Gender × Specialisation | 21.05 *** | 3.94 | 13.33–28.77 | <0.001 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −0.31 | 0.27 | −0.84–0.23 | 0.258 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 2 | −0.72 † | 0.29 | −1.30–−0.15 | 0.014 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 1 | 4.89 † | 2.11 | 0.75–9.04 | 0.021 | |

| Specialisation × Homeschooling 2 | 8.16 ** | 2.51 | 3.24–13.09 | 0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −3.42 *** | 0.96 | −5.31–−1.53 | <0.001 | |

| Specialisation × Gender × Homeschooling 2 | −5.58 *** | 1.14 | −7.81–−3.34 | <0.001 |

| Outcome | Predictors | B | SE (b) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.050/0.599 AIC/BIC = 9689.9/9792.1 | Intercept | 12.25 ** | 1.43 | 9.45–15.05 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.11–0.02 | 0.185 | |

| No. of children | −0.57 * | 0.2 | −0.97–−0.17 | 0.005 | |

| Relationship length | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.11–0.04 | 0.316 | |

| Family Income | −0.01 | 0.1 | −0.21–0.19 | 0.902 | |

| Education | −0.03 | 0.11 | −0.26–0.19 | 0.767 | |

| Equity | 2.33 | 4.45 | −6.39–11.05 | 0.601 | |

| Gender | −0.67 | 0.48 | −1.61–0.28 | 0.168 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.48 | 0.25 | −0.96–0.01 | 0.054 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.74 * | 0.29 | −1.31–−0.18 | 0.009 | |

| Gender × Equity | 3.62 | 2.28 | −0.85–8.09 | 0.112 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 1 | 0.24 | 0.12 | −0.01–0.48 | 0.056 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 0.28 † | 0.14 | 0.01–0.55 | 0.040 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 1 | −0.24 | 1.04 | −2.28–1.81 | 0.822 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 2 | −1.54 | 1.28 | −4.04–0.96 | 0.228 | |

| Equity × Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −1.21 † | 0.54 | −2.27–−0.15 | 0.025 | |

| Equity × Gender × Homeschooling 2 | −0.90 | 0.65 | −2.18–0.39 | 0.170 | |

| Anxiety Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.044/0.537 AIC/BIC = 9364.7/9467.0 | Intercept | 9.31 ** | 1.24 | 6.87–11.74 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.09–0.02 | 0.195 | |

| No. of children | −0.47 * | 0.18 | −0.82–−0.13 | 0.007 | |

| Relationship length | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.10–0.02 | 0.207 | |

| Family Income | 0.00 | 0.09 | −0.18–0.18 | 0.986 | |

| Education | −0.09 | 0.1 | −0.29–0.11 | 0.371 | |

| Equity | 4.53 | 3.85 | −3.01–12.07 | 0.239 | |

| Gender | −0.88 | 0.46 | −1.78–0.01 | 0.052 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.20 | 0.21 | −0.62–0.22 | 0.346 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.21 | 0.25 | −0.70–0.28 | 0.398 | |

| Gender × Equity | 0.91 | 2.15 | −3.31–5.13 | 0.674 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 1 | 0.31 * | 0.12 | 0.08–0.54 | 0.008 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 0.34 * | 0.13 | 0.08–0.60 | 0.009 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 1 | −0.39 | 0.9 | −2.16–1.37 | 0.663 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 2 | −1.93 | 1.1 | −4.09–0.24 | 0.081 | |

| Equity × Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −0.32 | 0.51 | −1.32–0.68 | 0.527 | |

| Equity × Gender × Homeschooling 2 | −0.43 | 0.62 | −1.65–0.78 | 0.483 | |

| Perceived Stress Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.053/0.509 AIC/BIC = 7721.3/7823.5 | Intercept | 10.11 ** | 0.73 | 8.68–11.55 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.04 † | 0.02 | −0.07–−0.01 | 0.014 | |

| No. of children | −0.19 | 0.1 | −0.39–0.01 | 0.069 | |

| Relationship length | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.04–0.04 | 0.935 | |

| Family Income | −0.12 † | 0.05 | −0.22–−0.01 | 0.028 | |

| Education | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.17–0.08 | 0.475 | |

| Equity | 1.17 | 2.25 | −3.25–5.59 | 0.603 | |

| Gender | 0.14 | 0.28 | −0.41–0.68 | 0.625 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −0.14 | 0.13 | −0.39–0.11 | 0.265 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −0.35 † | 0.15 | −0.63–−0.06 | 0.018 | |

| Gender × Equity | −0.31 | 1.32 | −2.90–2.27 | 0.811 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 1 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.13–0.15 | 0.847 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.10–0.21 | 0.465 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 1 | −0.46 | 0.53 | −1.50–0.57 | 0.379 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 2 | −0.52 | 0.65 | −1.79–0.75 | 0.424 | |

| Equity × Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −0.15 | 0.31 | −0.77–0.46 | 0.623 | |

| Equity × Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 0.14 | 0.38 | −0.60–0.89 | 0.707 | |

| Relationship Satisfaction Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.064/0.790 AIC/BIC = 8622.4/8724.6 | Intercept | 10.96 ** | 1.2 | 8.60–13.32 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.09–0.02 | 0.227 | |

| No. of children | 0.67 ** | 0.18 | 0.33–1.02 | <0.001 | |

| Relationship length | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04–0.09 | 0.444 | |

| Family Income | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.23–0.09 | 0.389 | |

| Education | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.17–0.13 | 0.820 | |

| Equity | −8.32 † | 3.85 | −15.86–−0.78 | 0.031 | |

| Gender | 0.36 | 0.29 | −0.20–0.92 | 0.210 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | 0.75 ** | 0.21 | 0.33–1.16 | <0.001 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | 0.65 * | 0.25 | 0.17–1.13 | 0.009 | |

| Gender × Equity | −0.55 | 1.35 | −3.20–2.11 | 0.685 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −0.14 | 0.07 | −0.28–0.00 | 0.056 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 2 | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.29–0.03 | 0.114 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 1 | 1.56 | 0.9 | −0.21–3.33 | 0.084 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 2 | 3.15 * | 1.1 | 0.99–5.32 | 0.004 | |

| Equity × Gender × Homeschooling 1 | 0.29 | 0.32 | −0.34–0.92 | 0.367 | |

| Equity × Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 0.41 | 0.39 | −0.35–1.17 | 0.288 | |

| Relationship Conflict Marginal R2/Conditional R2 = 0.071/0.670 AIC/BIC = 12,465.1/12,567.3 | Intercept | 38.01 ** | 3.55 | 31.06–44.97 | <0.001 |

| Parent age | −0.08 | 0.08 | −0.24–0.08 | 0.344 | |

| No. of children | −1.40 * | 0.51 | −2.40–−0.40 | 0.006 | |

| Relationship length | −0.15 | 0.09 | −0.33–0.03 | 0.097 | |

| Family Income | 0.53 † | 0.25 | 0.03–1.03 | 0.037 | |

| Education | −0.06 | 0.27 | −0.58–0.47 | 0.836 | |

| Equity | 2.35 | 11.14 | −19.48–24.18 | 0.833 | |

| Gender | 2.89 * | 1.09 | 0.76–5.01 | 0.008 | |

| Homeschooling 1 | −2.48 ** | 0.62 | −3.70–−1.27 | <0.001 | |

| Homeschooling 2 | −3.58 ** | 0.72 | −4.99–−2.18 | <0.001 | |

| Gender × Equity | −15.39 * | 5.13 | −25.45–−5.34 | 0.003 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 1 | −0.37 | 0.28 | −0.92–0.17 | 0.181 | |

| Gender × Homeschooling 2 | −0.79 † | 0.31 | −1.40–−0.19 | 0.011 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 1 | −1.40 | 2.61 | −6.51–3.72 | 0.592 | |

| Equity × Homeschooling 2 | −2.15 | 3.2 | −8.41–4.12 | 0.502 | |

| Equity × Gender × Homeschooling 1 | 2.22 | 1.22 | −0.16–4.60 | 0.068 | |

| Equity × Gender × Homeschooling 2 | 4.56 * | 1.47 | 1.67–7.45 | 0.002 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elgendi, M.M.; Stewart, S.H.; DesRoches, D.I.; Corkum, P.; Nogueira-Arjona, R.; Deacon, S.H. Division of Labour and Parental Mental Health and Relationship Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic-Mandated Homeschooling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417021

Elgendi MM, Stewart SH, DesRoches DI, Corkum P, Nogueira-Arjona R, Deacon SH. Division of Labour and Parental Mental Health and Relationship Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic-Mandated Homeschooling. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):17021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417021

Chicago/Turabian StyleElgendi, Mariam M., Sherry H. Stewart, Danika I. DesRoches, Penny Corkum, Raquel Nogueira-Arjona, and S. Hélène Deacon. 2022. "Division of Labour and Parental Mental Health and Relationship Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic-Mandated Homeschooling" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 17021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417021

APA StyleElgendi, M. M., Stewart, S. H., DesRoches, D. I., Corkum, P., Nogueira-Arjona, R., & Deacon, S. H. (2022). Division of Labour and Parental Mental Health and Relationship Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic-Mandated Homeschooling. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 17021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417021