Relational Victimization and Video Game Addiction among Female College Students during COVID-19 Pandemic: The Roles of Social Anxiety and Parasocial Relationship

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Relational Victimization and Video Game Addiction

1.2. The Role of Social Anxiety

1.3. The Role of Parasocial Relationships

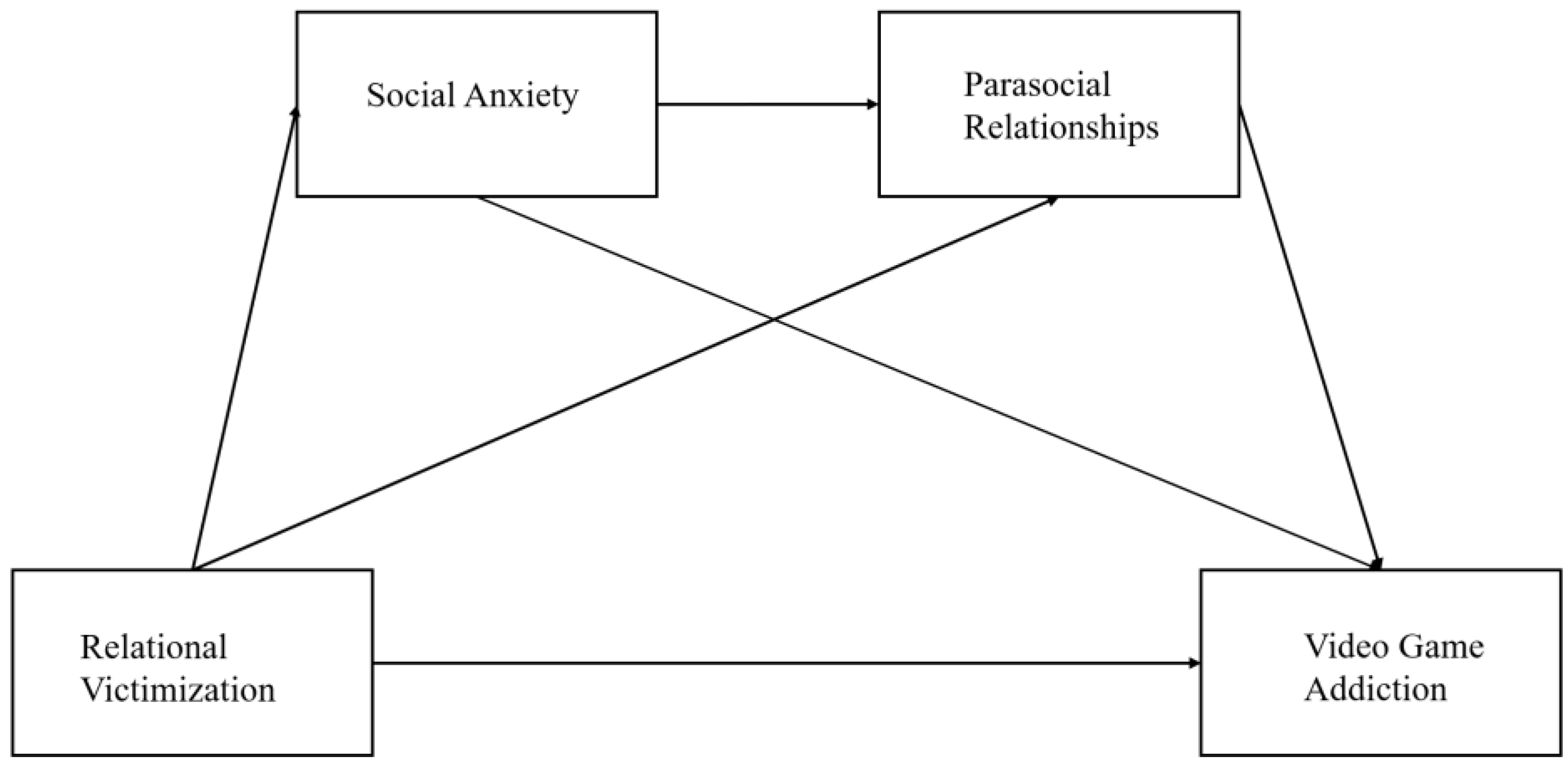

1.4. The Serial Mediating Effect of Social Anxiety and Parasocial Relationships

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Relational Victimization

2.2.2. Social Anxiety

2.2.3. Parasocial Relationships with Virtual Characters

2.2.4. Video Game Addiction

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Correlation Analysis

3.2. Testing for the Proposed Model

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of Relational Victimization on Video Game Addiction

4.2. The Mediating Roles of Social Anxiety and Parasocial Relationships

4.3. Limitations and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gómez-Galán, J.; Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Martínez-López, J.Á. Exploratory study on video game addiction of college students in a pandemic scenario. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2021, 10, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/markets/417/topic/478/video-gaming-esports/#overview (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Edition, F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 2013, 21, 591–643. [Google Scholar]

- Abou Naaj, M.; Nachouki, M.; LEzzar, S. The impact of Video Game Addiction on Students’ Performance During COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), Lancaster, UK, 17–21 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nugraha, Y.P.; Awalya, A.; Mulawarman, M. Predicting Video Game Addiction: The Effects of Composite Regulatory Focus and Interpersonal Competence Among Indonesian Teenagers During COVID-19 Pandemic. Islam. Guid. Couns. J. 2021, 4, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chess, S. A time for play: Interstitial time, Invest/Express games, and feminine leisure style. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Audio-Video and Digital Publishing Association. Available online: http://www.199it.com/archives/983442.html (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Morrissette, M. School closures and social anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, A.; Gasser, O.; Lichtblau, F.; Pujol, E.; Poese, I.; Dietzel, C.; Wagner, D.; Wichtlhuber, M.; Tapiador, J.; Vallina-Rodriguez, N. The lockdown effect: Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on internet traffic. In Proceedings of the ACM Internet Measurement Conference, online, 27–29 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Meng, S.; Sun, Y.; Schumann, G.; Kosten, T.; Strang, J.; Lu, L.; Shi, J. Brief report: Increased addictive internet and substance use behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Am. J. Addict. 2020, 29, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardina, A.; Di Blasi, M.; Schimmenti, A.; King, D.L.; Starcevic, V.; Billieux, J. Online gaming and prolonged self-isolation: Evidence from Italian gamers during the COVID-19 outbreak. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2021, 18, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Luo, T.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Deng, Q.; Liao, Y. Gaming in China Before the COVID-19 Pandemic and After the Lifting of Lockdowns: A Nationwide Online Retrospective Survey. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022; 1–13, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Nam, T.-H.; Hwang, M.H. Attachment style, stressful events, and Internet gaming addiction in Korean university students. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 154, 109724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Cai, G.; Xiong, C.; Huang, J. Relative deprivation and game addiction in left-behind children: A moderated mediation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 639051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2001, 17, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, G.; Tian, Y.; Xu, L.; Duan, C. Ostracism and Problematic Smartphone Use: The Mediating Effect of Social Self-Efficacy and Moderating Effect of Rejection Sensitivity. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, G.A.; Jagaveeran, M.; Goh, Y.-N.; Tariq, B. The impact of type of content use on smartphone addiction and academic performance: Physical activity as moderator. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, L.; La Torre, G.; Fiore, M.; Grumi, S.; Gentile, D.A.; Ferrante, M.; Miccoli, S.; Di Blasio, P. Internet gaming addiction in adolescence: Risk factors and maladjustment correlates. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2018, 16, 888–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yu, C.; Chen, J.; Sheng, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, L. The association between parental psychological control, deviant peer affiliation, and internet gaming disorder among Chinese adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, J. Peer victimization and problematic internet game use among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model of school engagement and grit. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 1943–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C.; Peets, K. Bullies, victims, and bully-victim relationships in middle childhood and early adolescence. In Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 322–340. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, S.; Stockton, H. The multidimensional peer victimization scale: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 42, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Nie, Q.; Zhou, J. The relationship between bullying victimization and online game addiction among Chinese early adolescents: The potential role of meaning in life and gender differences. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Luo, X.; Zheng, R.; Jin, X.; Mei, L.; Xie, X.; Gu, H.; Hou, F.; Liu, L.; Luo, X. The role of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and school functioning in the association between peer victimization and internet addiction: A moderated mediation model. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 256, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, S.; Gurdal, S.; Ander, B.; Sorbring, E. Reported changes in adolescent psychosocial functioning during the COVID-19 outbreak. Adolescents 2021, 1, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.E.; Newman, M.G. Self-and other-perceptions of interpersonal problems: Effects of generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and depression. J. Anxiety Disord. 2019, 65, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X. The moderating role of state attachment anxiety and avoidance between social anxiety and social networking sites addiction. Psychol. Rep. 2020, 123, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bérail, P.; Guillon, M.; Bungener, C. The relations between YouTube addiction, social anxiety and parasocial relationships with YouTubers: A moderated-mediation model based on a cognitive-behavioral framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 99, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, M.; Copeland-Stewart, A. Playing video games during the COVID-19 pandemic and effects on players’ well-being. Games Cult. 2022, 17, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R. The motivational pull of video game feedback, rules, and social interaction: Another self-determination theory approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowert, R.; Oldmeadow, J.A. Playing for social comfort: Online video game play as a social accommodator for the insecurely attached. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, S.; Malecki, C.K.; Emmons, J. Keep your friends close: Exploring the associations of bullying, peer social support, and social anxiety. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 25, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; He, J.; Lin, S.; Sun, X.; Longobardi, C. Cyberbullying victimization and adolescent depression: The mediating role of psychological security and the moderating role of growth mindset. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, F.; Bellmore, A. Connecting online and offline social skills to adolescents’ peer victimization and psychological adjustment. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, E.B.; Barker, E.D.; Luo, Q.; Banaschewski, T.; Bokde, A.L.; Bromberg, U.; Büchel, C.; Desrivières, S.; Flor, H.; Frouin, V. Peer victimization and its impact on adolescent brain development and psychopathology. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 3066–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Stadulis, R.; Neal-Barnett, A. Assessing the effects of the acting White accusation among Black girls: Social anxiety and bullying victimization. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2018, 110, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bults, M.; Beaujean, D.J.; de Zwart, O.; Kok, G.; van Empelen, P.; van Steenbergen, J.E.; Richardus, J.H.; Voeten, H.A. Perceived risk, anxiety, and behavioural responses of the general public during the early phase of the Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands: Results of three consecutive online surveys. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Miao, M.; Lim, J.; Li, M.; Nie, S.; Zhang, X. Is lockdown bad for social anxiety in COVID-19 regions?: A national study in the SOR perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, R.L.; Rickwood, D.J. A systematic review of the mental health outcomes associated with Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 576–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prizant-Passal, S.; Shechner, T.; Aderka, I.M. Social anxiety and internet use–A meta-analysis: What do we know? What are we missing? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Fu, Y.; Hou, X.; Yu, L. The mediating role of escape motivation and flow experience between frustration and online game addiction among university students. Chin. J. Behav. Med. Brain Sci. 2021, 30, 327–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat, S.; Jeong, E.J.; Kim, D.J. The role of individuals’ need for online social interactions and interpersonal incompetence in digital game addiction. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibble, J.L.; Hartmann, T.; Rosaen, S.F. Parasocial interaction and parasocial relationship: Conceptual clarification and a critical assessment of measures. Hum. Commun. Res. 2016, 42, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffner, C.A.; Bond, B.J. Parasocial relationships, social media, & well-being. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101306. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, S.; Xiao, C. What shapes a parasocial relationship in RVGs? The effects of avatar images, avatar identification, and romantic jealousy among potential, casual, and core players. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 139, 107504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, L.; Lian, S.; Zhai, S.; Zhang, D. The impact of interpersonal alienation on excessive Internet fiction reading: Analysis of parasocial relationship as a mediator and relational-interdependent self-construal as a moderator. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T. Parasocial interaction, parasocial relationships, and well-being. In The Routledge Handbook of Media Use and Well-Being; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero, T.E. Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Commun. Soc. 2000, 3, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, D.; Richard Wohl, R. Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry 1956, 19, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Chen, Z. A study on psychopathology and psychotherapy of Internet addiction. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 14, 596. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-L. How vloggers embrace their viewers: Focusing on the roles of para-social interactions and flow experience. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 49, 101364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakey, B.; Cooper, C.; Cronin, A.; Whitaker, T. Symbolic providers help people regulate affect relationally: Implications for perceived support. Pers. Relatsh. 2014, 21, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, C.; Floyd, K. Affection substitution: The effect of pornography consumption on close relationships. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 36, 3887–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Q. Peer victimization and adolescent mobile social addiction: Mediation of social anxiety and gender differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-Q.; Yang, X.-J.; Hu, Y.-T.; Zhang, C.-Y. Peer victimization, self-compassion, gender and adolescent mobile phone addiction: Unique and interactive effects. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Lin, B. The Impact of College Students’ Social Anxiety on Interpersonal Communication Skills: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sci. Soc. Res. 2022, 4, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, M.; Conroy, E.; Ramsbottom, N.; Smithies, T.; Toth, A.; Campbell, M. Gaming your mental health: A narrative review on mitigating symptoms of depression and anxiety using commercial video games. JMIR Serious Games 2021, 9, e26575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, B.J. The development and influence of parasocial relationships with television characters: A longitudinal experimental test of prejudice reduction through parasocial contact. Commun. Res. 2021, 48, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, J.; Jones, K. Revision of the Chinese version of olweus child bullying questionnaire. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 1999, 15, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at school. In Aggressive Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 97–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.D.; Wang, X.L.; Ma, H. Manual of the Mental Health Rating Scale. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1999, 13, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein, A.; Scheier, M.F.; Buss, A.H. Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1975, 43, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y. The Influence of Anime Characters on the Psychological Identity and Behavior of Anime Fans from the Perspective of Parasocial Relationships. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm, H.; Hartmann, T. The PSI-Process Scales. A new measure to assess the intensity and breadth of parasocial processes. Eur. J. Commun. Res. 2008, 33, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasubramanian, S.; Kornfield, S. Japanese anime heroines as role models for US youth: Wishful identification, parasocial interaction, and intercultural entertainment effects. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 2012, 5, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jou, M.; Wang, B.; An, Y.; Li, Z. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of the 7-item game addiction scale (GAS) among Chinese college students. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, J.S.; Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J. Development and validation of a game addiction scale for adolescents. Media Psychol. 2009, 12, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhonglin, D.T.W. Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: Problems and suggestions. J. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 43, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Triberti, S.; Milani, L.; Villani, D.; Grumi, S.; Peracchia, S.; Curcio, G.; Riva, G. What matters is when you play: Investigating the relationship between online video games addiction and time spent playing over specific day phases. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2018, 8, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, P.-F.; Li, B.-Q.; Xu, W.-J.; Li, W.; Zhou, B. The influence of interpersonal relationships on school adaptation among Chinese university students during COVID-19 control period: Multiple mediating roles of social support and resilience. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 285, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontillo, M.; Tata, M.C.; Averna, R.; Demaria, F.; Gargiullo, P.; Guerrera, S.; Pucciarini, M.L.; Santonastaso, O.; Vicari, S. Peer victimization and onset of social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vessey, J.A.; Difazio, R.L.; Neil, L.K.; Dorste, A. Is There a Relationship Between Youth Bullying and Internet Addiction? An Integrative Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022; 1–25, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.-f.; Shi, X.-h.; Yao, L.-s.; Yang, W.-c.; Jin, S.-y.; Xu, L. Social Exclusion and Depression among undergraduate students: The mediating roles of rejection sensitivity and social self-efficacy. Curr. Psychol. 2022; 1–10, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone-Lopez, K.; Esbensen, F.-A.; Brick, B.T. Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: Gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2010, 8, 332–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Du, R. Effects of Overt and Relational Bullying on Adolescents’ Subjective Well-Being: The Mediating Mechanisms of Social Capital and Psychological Capital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Jian, S.; Dong, M.; Gao, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, H.; Chen, H.; Gai, X. Childhood trauma and suicidal ideation among Chinese university students: The mediating effect of Internet addiction and school bullying victimisation. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, E152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.; Delfabbro, P.; Griffiths, M. Video game structural characteristics: A new psychological taxonomy. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2010, 8, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintegral. Available online: https://www.mintegral.com/cn/blog/33421 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Barnett, M.D.; Maciel, I.V.; Johnson, D.M.; Ciepluch, I. Social anxiety and perceived social support: Gender differences and the mediating role of communication styles. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, S.; Karakoc, A.; Can Gurkan, O.; Onan, N.; Unsal Barlas, G. Investigation of the online game addiction level, sociodemographic characteristics and social anxiety as risk factors for online game addiction in middle school students. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Sheng, J.-R.; Wang, H.-Z. The association between mobile game addiction and depression, social anxiety, and loneliness. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavicini, F.; Pepe, A.; Mantovani, F. Commercial off-the-shelf video games for reducing stress and anxiety: Systematic review. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e28150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, S. Bowling with our imaginary friends. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2002, 23, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stever, G.S. Evolutionary theory and reactions to mass media: Understanding parasocial attachment. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2017, 6, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. Computer game playing in early adolescence. Youth Soc. 1997, 29, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qie, R. Female Dating Simulator Gamers’ Motivations and Developing Parasocial Relationships with Game Characters. Master’s Thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, A.M. Uses-and-gratifications perspective on media effects. In Media Effects; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009; pp. 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Song, I.; Larose, R.; Eastin, M.S.; Lin, C.A. Internet gratifications and Internet addiction: On the uses and abuses of new media. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2004, 7, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberlin, K.A.; Atkin, D.J. Mobile gaming and Internet addiction: When is playing no longer just fun and games? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 126, 106989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Formosa, J.; Perry, R.; Lalande, D.; Türkay, S.; Obst, P.; Mandryk, R. Unsatisfied needs as a predictor of obsessive passion for videogame play. Psychol. Pop. Media 2022, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K. FANatics: Systematic literature review of factors associated with celebrity worship, and suggested directions for future research. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Cho, H. Fostering parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media: Implications for celebrity endorsement. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, A.C.; Caplan, S.E. Social anxiety and computer-mediated communication during initial interactions: Implications for the hyperpersonal perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koydemir, S.; Essau, C.A. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in young people: A cross-cultural perspective. In Understanding Uniqueness and Diversity in Child and Adolescent Mental Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Wu, N.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Z.; Cui, N.; Xu, L.; Yang, X. Be loyal but not addicted: Effect of online game social migration on game loyalty and addiction. J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 16, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 19.41 | 1.38 | ||||

| 2. Relational Victimization | 1.47 | 0.85 | 1 | |||

| 3. Social Anxiety | 3.21 | 0.80 | 0.20 *** | 1 | ||

| 4. Parasocial Relationship | 2.65 | 0.88 | 0.28 *** | 0.29 *** | 1 | |

| 5. Video Game Addition | 1.83 | 0.78 | 0.30 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.44 *** | 1 |

| Outcome | Predictors | R2 | F | β | t | LLCI | ULCL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | Age | 0.05 | 10.61 *** | 0.05 | 1.58 | −0.01 | 0.12 |

| RV | 0.19 | 4.09 *** | 0.10 | 0.29 | |||

| PRs | Age | 0.14 | 22.91 *** | 0.01 | 0.37 | −0.05 | 0.08 |

| RV | 0.23 | 4.99 *** | 0.14 | 0.32 | |||

| SA | 0.24 | 5.34 *** | 0.15 | 0.33 | |||

| VGA | Age | 0.27 | 40.01 *** | 0.01 | 0.49 | −0.04 | 0.07 |

| RV | 0.17 | 3.80 *** | 0.08 | 0.25 | |||

| SA | 0.21 | 4.89 *** | 0.13 | 0.30 | |||

| PRs | 0.33 | 7.46 *** | 0.24 | 0.42 |

| Path | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | Relative Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.39 | ||

| Direct effect | RV→VGA | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.25 | |

| Indirect effect | RV→SA→VGA | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 13.82% |

| RV→PR→VGA | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 25.43% | |

| RV→SA→PR→VGA | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 5.25% | |

| Total indirect effect | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 44.50% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niu, G.; Jin, S.; Xu, F.; Lin, S.; Zhou, Z.; Longobardi, C. Relational Victimization and Video Game Addiction among Female College Students during COVID-19 Pandemic: The Roles of Social Anxiety and Parasocial Relationship. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16909. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416909

Niu G, Jin S, Xu F, Lin S, Zhou Z, Longobardi C. Relational Victimization and Video Game Addiction among Female College Students during COVID-19 Pandemic: The Roles of Social Anxiety and Parasocial Relationship. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16909. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416909

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Gengfeng, Siyu Jin, Fang Xu, Shanyan Lin, Zongkui Zhou, and Claudio Longobardi. 2022. "Relational Victimization and Video Game Addiction among Female College Students during COVID-19 Pandemic: The Roles of Social Anxiety and Parasocial Relationship" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16909. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416909

APA StyleNiu, G., Jin, S., Xu, F., Lin, S., Zhou, Z., & Longobardi, C. (2022). Relational Victimization and Video Game Addiction among Female College Students during COVID-19 Pandemic: The Roles of Social Anxiety and Parasocial Relationship. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16909. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416909