Climate Change and African Migrant Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

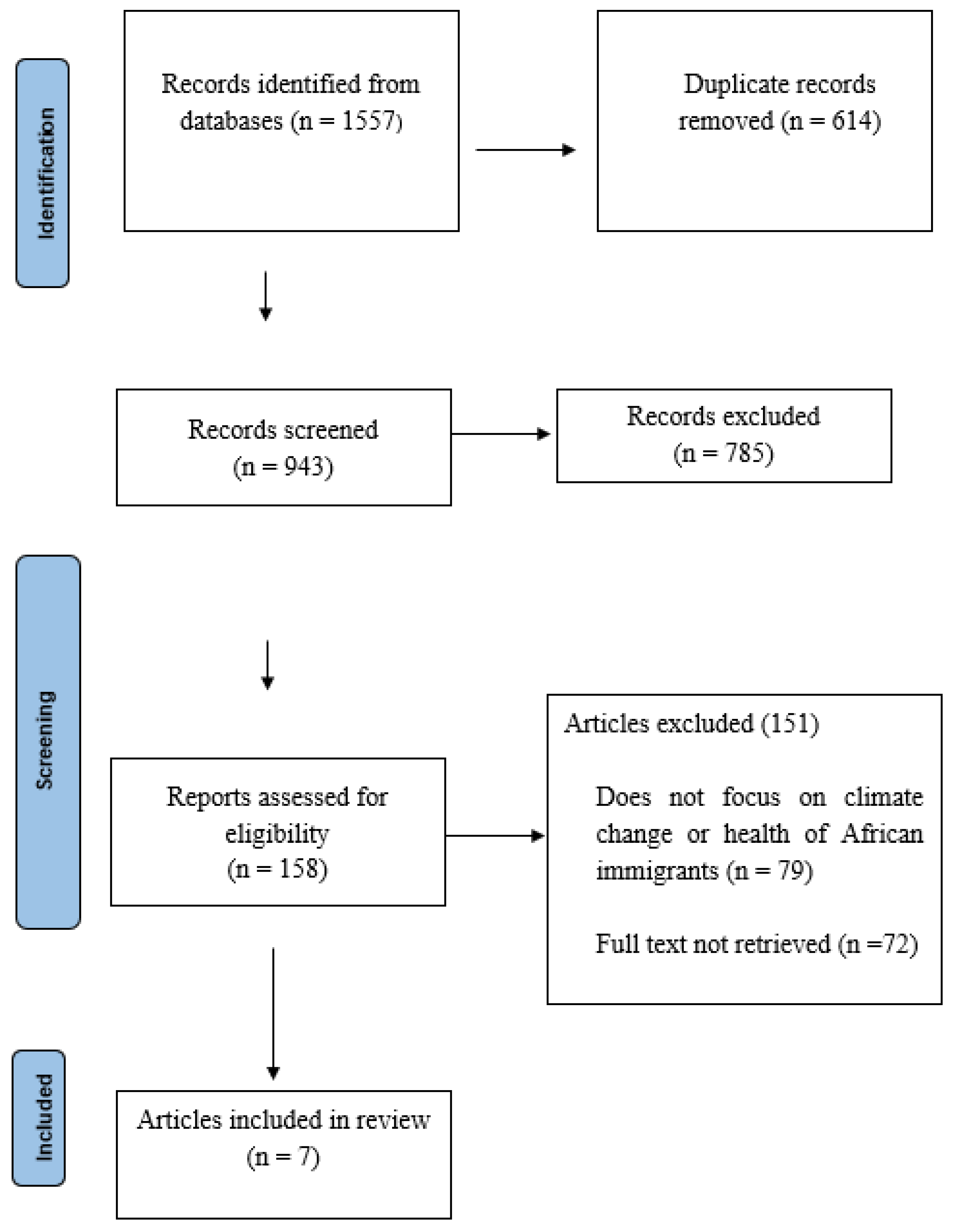

2. Methods

2.1. Stage 1: Developing the Research Question

2.2. Stage 2: Identifying the Relevant Studies

2.3. Stage 3: Article Selection

2.4. Stage 4: Data Charting and Data Extraction

2.5. Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Poor Hygiene/Sanitation

3.3. Access to Healthcare

3.4. Mental Health and Social Capital

3.5. Malnutrition

3.6. Respiratory Health

3.7. Premature Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (IDMC). December 2019. Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/media-centres/internal-displacement-costs-africa-4-billion-every-year (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Tanner, T.; Lewis, D.; Wrathall, D.; Bronen, R.; Cradock-Henry, N.; Huq, S.; Lawless, C.; Nawrotzki, R.; Prasad, V.; Rahman, M.A.; et al. Livelihood resilience in the face of climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Generation 2030 Africa 2.0. November 2017. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/generation-2030-africa-2-0/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Black, R.; Adger, W.N.; Arnell, N.W.; Dercon, S.; Geddes, A.; Thomas, D. The effect of environmental change on human migration. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Boykoff, M.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Capstick, S.; Chambers, J.; et al. The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. Lancet 2019, 394, 1836–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelle, R. Malaria ‘Spreading to New Altitudes’. 7 March 2014. Available online: www.bbc.com/news/health-26470755 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Tailoring Malaria Interventions in the COVID-19 Response, 2020. 9 April 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/tailoring-malaria-interventions-in-the-covid-19-response (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoo, O.S.; Smith, S.I.; Ujah, I.A.O.; Oladele, D.; David, N.; Oyedeji, K.S.; Nwaokorie, F.; Bamidele, T.A.; Afocha, E.E.; Awoderu, O.; et al. Socio-economic and health challenges of internally-displaced persons as a result of 2012 flooding in Nigeria. Ceylon J. Sci. 2018, 47, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, O.; Khan, M. The Dadaab camps-Mitigating the effects of drought in the Horn (perspective). PLoS Curr. 2011, 3, RRN1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, K.C.; Bell, M.L. Do fine particulate air pollution (PM2.5) exposure and its attributable premature mortality differ for immigrants compared to those born in the United States? Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaney, A.K.; Winter, S.J. Climate-driven migration: An exploratory case study of Maasai health perceptions and help-seeking behaviors. Int. J. Public Health 2016, 61, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindvall, K.; Kinsman, J.; Abraha, A.; Dalmar, A.; Abdullahi, M.F.; Godefay, H.; Lerenten Thomas, L.; Mohamoud, M.O.; Mohamud, B.K.; Musumba, J.; et al. Health status and health care needs of drought-related migrants in the Horn of Africa—A qualitative investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyoka, R.; Omony, J.; Mwalili, S.M.; Achia, T.N.; Gichangi, A.; Mwambi, H. Effect of climate on incidence of respiratory syncytial virus infections in a refugee camp in Kenya: A non-Gaussian time-series analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giorgi, E.; Michielin, P.; Michielin, D. Perception of climate change, loss of social capital and mental health in two groups of migrants from African countries. Ann. Dell’istituto Super. Sanita 2020, 56, 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cianconi, P.; Betrò, S.; Janiri, L. The impact of climate change on mental health: A systematic descriptive review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mpandeli, S.; Nhamo, L.; Hlahla, S.; Naidoo, D.; Liphadzi, S.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T. Migration under climate change in southern Africa: A nexus planning perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Climate Change and Health. 1 February 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (accessed on 10 December 2022).

| Authors, Year, Location | Article Type | Sample Size | Age Range (Years) | Type of Immigrants | Type of Climate Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoo et al., 2018 [10], Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | 432 | 18–100 | IDPs | Flooding |

| Dar and Khan, 2011 [11], Kenya | Report | NR | NR | Refugees | Drought |

| Di Giorgi et al., 2020 [6], Multiple locations | Cross-sectional study | 100 | 27.9 (mean) | Migrants from Nigeria, Ghana, and Cameroon | Drought |

| Fong et al., 2021 [12], USA | Cross-sectional study | 1.5 million | NR | African immigrants | Particulate matter |

| Heaney and Winter, 2016 [13], Tanzania | Qualitative study | 28 | NR | Rural-to-urban migrants | Drought |

| Lindvall et al., 2020 [14], Multiple locations | Qualitative study | 39 | NR | Refugees and IDPs | Drought, flooding |

| Nyoka et al., 2017 [15], Kenya | Cohort study | NR | Children < 5 | Refugees | Wind speed, dew point, rainfall, and temperature |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanni, O.; Salami, B.; Oluwasina, F.; Ojo, F.; Kennedy, M. Climate Change and African Migrant Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416867

Sanni O, Salami B, Oluwasina F, Ojo F, Kennedy M. Climate Change and African Migrant Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416867

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanni, Omolara, Bukola Salami, Folajinmi Oluwasina, Folakemi Ojo, and Megan Kennedy. 2022. "Climate Change and African Migrant Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416867

APA StyleSanni, O., Salami, B., Oluwasina, F., Ojo, F., & Kennedy, M. (2022). Climate Change and African Migrant Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416867