Parental Psychological Control and Addiction Behaviors in Smartphone and Internet: The Mediating Role of Shyness among Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Associations between Parental Psychological Control and Addiction Behaviors Surrounding Smartphones and the Internet

1.2. Parental Psychological Control, Shyness, and Addiction Behaviors Surrounding Smartphones and the Internet

1.3. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Parental Psychological Control

2.2.2. Smartphone Addiction

2.2.3. Internet Addiction

2.2.4. Shyness

2.3. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Study Variables

3.2. Measurement Model

3.3. Structural Equation Modeling

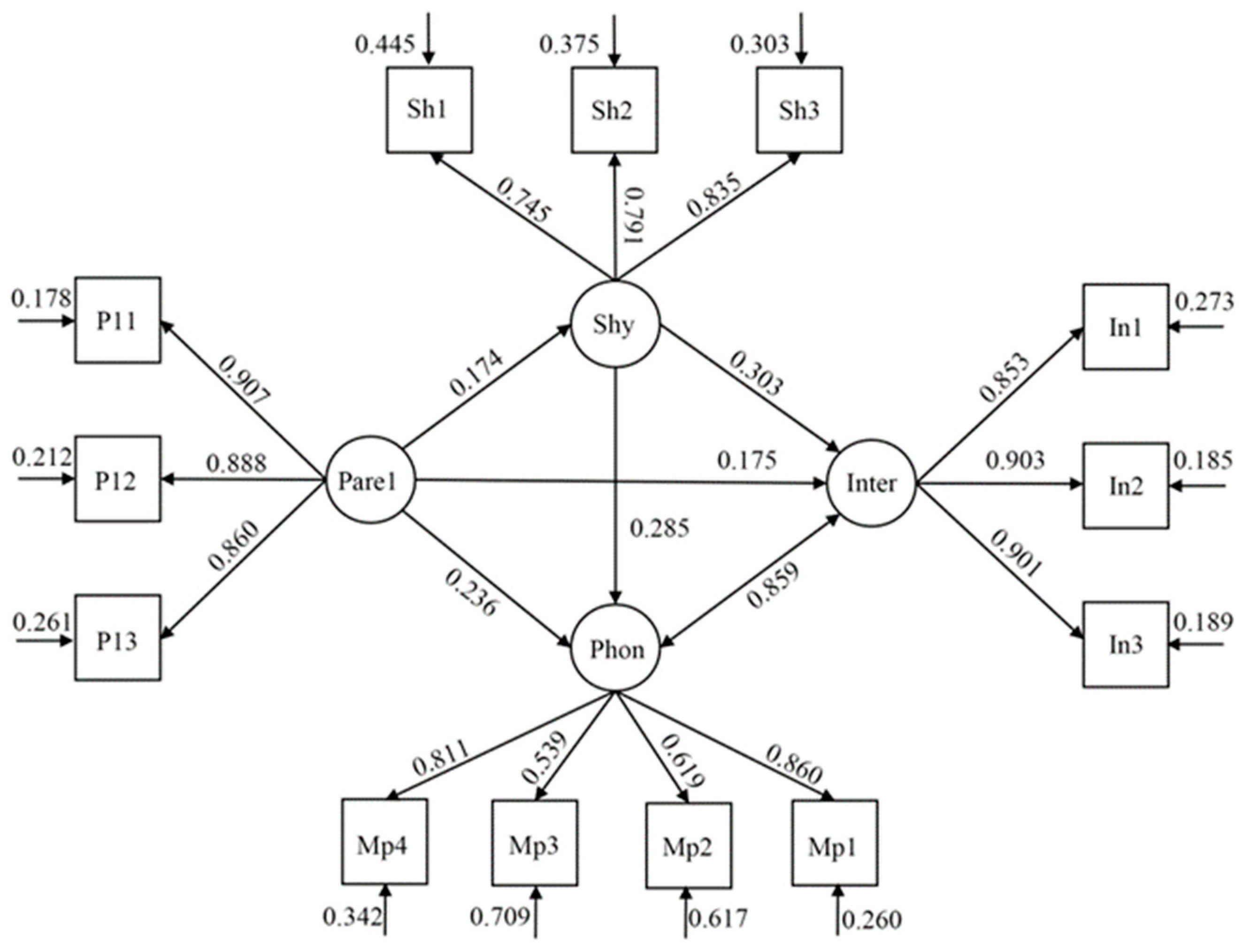

3.3.1. Guilt Induction, Shyness, and Addiction Behaviors

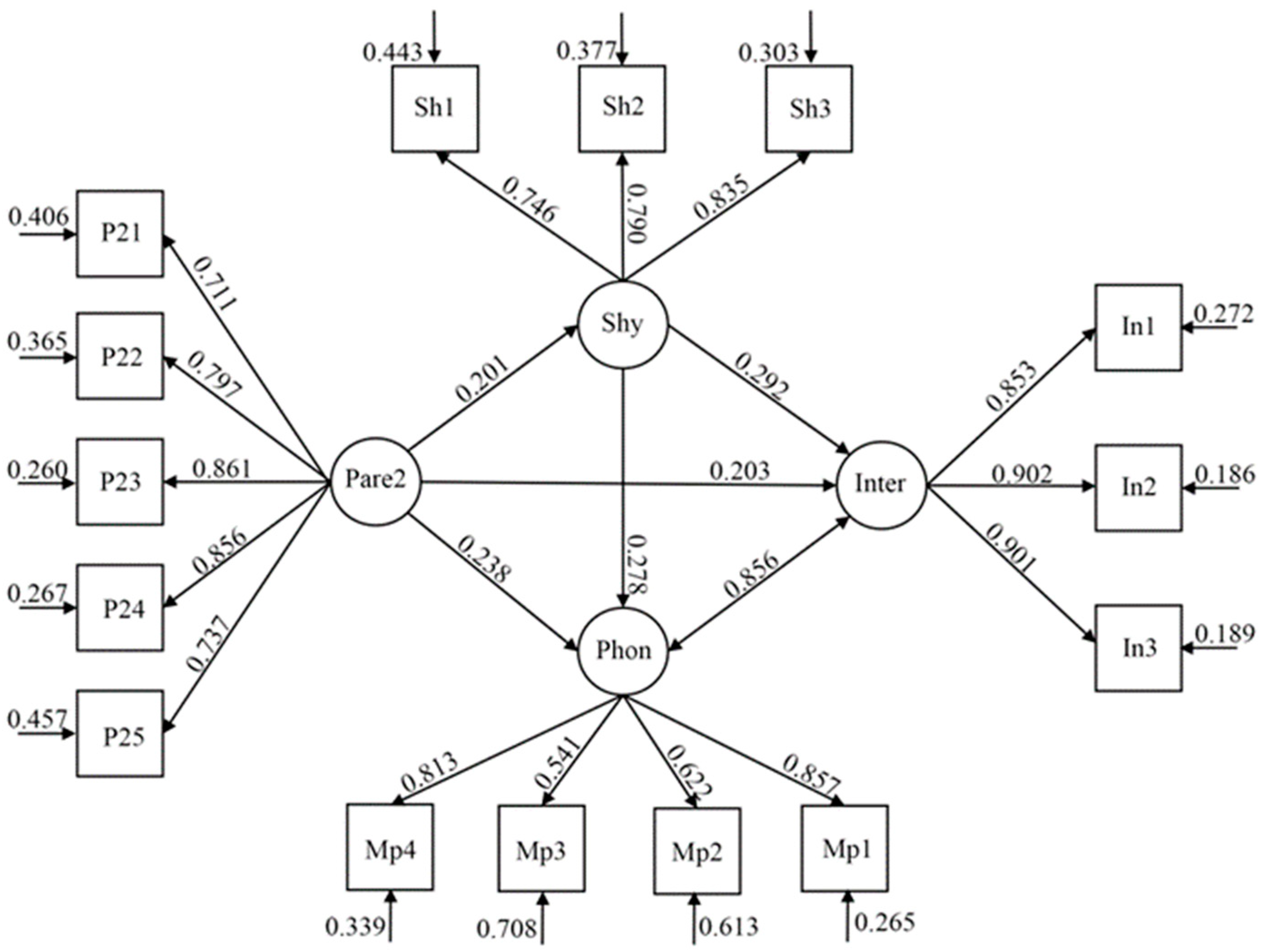

3.3.2. Love Withdrawal, Shyness, and Addiction Behaviors

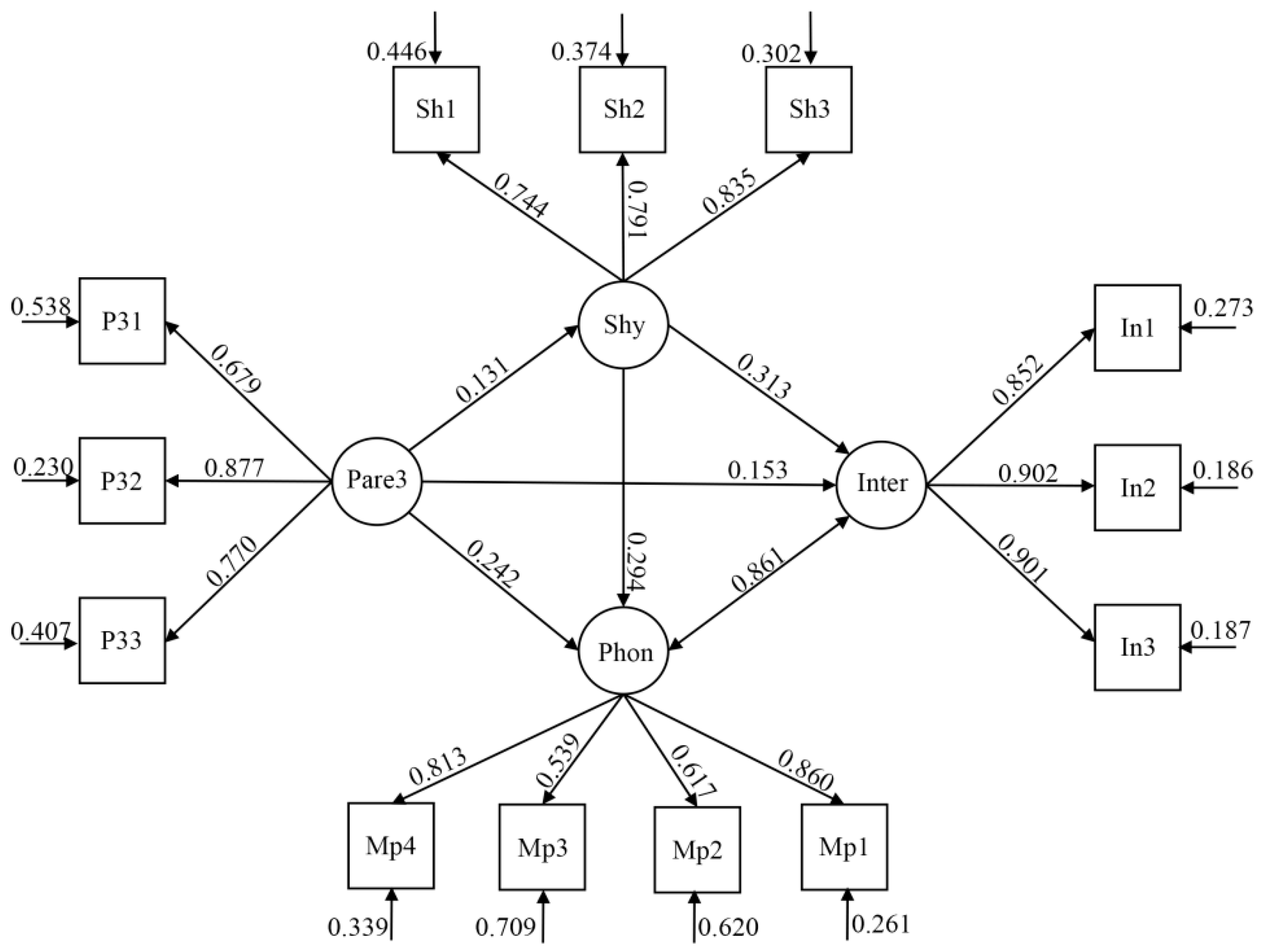

3.3.3. Authority Assertion, Shyness, and Addiction Behaviors

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cha, S.-S.; Seo, B.-K. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction in middle school students in Korea: Prevalence, social networking service, and game use. Health Psychol. Open 2018, 5, 2055102918755046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin Jeong, Y.; Suh, B.; Gweon, G. Is smartphone addiction different from Internet addiction? Comparison of addiction-risk factors among adolescents. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Niu, X. The association between social anxiety and mobile phone addiction: A three-level meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 130, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Choliz, M. Mobile-phone addiction in adolescence: The test of mobile phone dependence (TMD). Prog. Health Sci. 2012, 2, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, H.; Cheong, C.M.; Li, S.; Lu, M. The relationship between coping style and Internet addiction among mainland Chinese students: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaertner, A.E.; Rathert, J.L.; Fite, P.J.; Vitulano, M.; Wynn, P.T.; Harber, J. Sources of parental knowledge as moderators of the relation between parental psychological control and relational and physical/verbal aggression. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Zhang, Q.; Ran, G.; Li, S.; Niu, X. Relationship between parental psychological control and problem behaviours in youths: A three-level meta-analysis. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 112, 104900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 3296–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Ceci, S.J. Nature-nuture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychol. Rev. 1994, 101, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.-K.; Yue, X.D.; Wong, D.S.-W. Addictive internet use and parenting patterns among secondary school students in Guangzhou and Hong Kong. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Q.X. The association between parental psychological control and adolescent smartphone addiction: The role of online psychological needs satisfaction and environmental sensitivity. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2022, 38, 254–262. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, D.; Newman, J. Parental behavioral and psychological control and problematic Internet use among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of self-control. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D.T.; Zhu, X.; Ma, C.M. The influence of parental control and parent-child relational qualities on adolescent internet addiction: A 3-year longitudinal study in Hong Kong. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Nie, X.; Zhang, D.; Hu, Y. The relationship between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use in early Chinese adolescence: A repeated-measures study at two time-points. Addict. Behav. 2022, 125, 107142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Yu, C.; Chen, J.; Sheng, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, L. The association between parental psychological control, deviant peer affiliation, and internet gaming disorder among Chinese adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wu, J.; Guo, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Kou, Y. Parental Psychological Control and Adolescents’ Problematic Mobile Phone Use: The Serial Mediation of Basic Psychological Need Experiences and Negative Affect. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 31, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, D.; Ji, J.; Fu, H. Development of mobile internet addiction and a discussion on the concept. Chin. J. Behav. Med. Brain Sci. 2015, 24, 1138–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.-W.; Kim, D.-J.; Choi, J.-S.; Ahn, H.; Choi, E.-J.; Song, W.-Y.; Kim, S.; Youn, H. Comparison of risk and protective factors associated with smartphone addiction and Internet addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Jang, H.M.; Lee, Y.; Lee, D.; Kim, D.-J. Effects of internet and smartphone addictions on depression and anxiety based on propensity score matching analysis. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, J.-Y.; Choi, S.-W.; Kim, D.-J.; Choi, J.-S.; Lee, J.; Ahn, H.; Choi, E.-J.; Song, W.-Y. Latent class analysis on internet and smartphone addiction in college students. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ran, G.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, H. Behavioral inhibition system and self-esteem as mediators between shyness and social anxiety. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudasill, K.M.; Prokasky, A.; Tu, X.; Frohn, S.; Sirota, K.; Molfese, V.J. Parent vs. teacher ratings of children’s shyness as predictors of language and attention skills. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2014, 34, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nelson, L.J.; Hart, C.H.; Wu, B.; Yang, C.; Roper, S.O.; Jin, S. Relations between Chinese mothers’ parenting practices and social withdrawal in early childhood. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2006, 30, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.R.; Tserakhava, V.; Miller, C.J. My child is shy and has no friends: What does parenting have to do with it? J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarra-Nezhad, M.; Kiuru, N.; Aunola, K.; Zarra-Nezhad, M.; Ahonen, T.; Poikkeus, A.M.; Lerkkanen, M.K.; Nurmi, J.E. Social withdrawal in children moderates the association between parenting styles and the children’s own socioemotional development. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Geng, J.; Jou, M.; Gao, F.; Yang, H. Relationship between shyness and mobile phone addiction in Chinese young adults: Mediating roles of self-control and attachment anxiety. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chak, K.; Leung, L. Shyness and locus of control as predictors of internet addiction and internet use. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2004, 7, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Gao, Y.J.; Deng, Q.Y.; Peng, M.; Gao, F.Q. The relationship between shyness and mobile phone dependence in middle school students: A moderated mediation model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2021, 1, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, P.L.; Chester, A. Shyness and the internet: Social problem or panacea? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 2649–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Liu, R.-D.; Oei, T.-P.; Zhen, R.; Jiang, S.; Sheng, X. The mediating and moderating roles of social anxiety and relatedness need satisfaction on the relationship between shyness and problematic mobile phone use among adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suler, J.R. To get what you need: Healthy and pathological Internet use. CyberPsychol. Behav. 1999, 2, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Chen, H. The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1592–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, L. Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. J. Child. Media 2008, 2, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.S. Internet Addiction: The Emergence of a New Clinical Disorder. CyberPsychol. Behav. 1998, 1, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The Current Situation and Intervention Research on Negative Life Events, Self-Esteem and Internet Addiction of Junior High School Students. Master’s Dissertation, Yan’an University, Yan’an, China, 2021, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Q.Q. Childhood Psychological Abuse and Neglect on Adolescent Internet Addiction: The Mediating Role of Emotional Intelligence and Resilience. Master’s Dissertation, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, China, 2020, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Cheek, J.M.; Buss, A.H. Shyness and sociability. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 7th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.L.; Gillaspy, J.A., Jr.; Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Kuo, F.-Y. A study of Internet addiction through the lens of the interpersonal theory. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugliandolo, M.; Costa, S.; Kuss, D.; Cuzzocrea, F.; Verrastro, V. Technological addiction in adolescents: The interplay between parenting and psychological basic needs. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.B.; Zhang, G.Y. Effect of family factors on mental health of non-only children. China J. Health Psychol. 2019, 27, 1536–1539. [Google Scholar]

- Romm, K.F.; Metzger, A. Parental psychological control and adolescent problem behaviors: The role of depressive symptoms. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 2206–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. The Influence of Parenting Styles on College Students’ Mobile Phone Dependence: The Multiple Intermediaries Role of Social Support and Loneliness. Master’s Dissertation, Hu Nan Normal University, Changsha, China, 2018, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, G.; Barron, I.; Lala, E.; Oulbeid, B. Dispossession in occupied Palestine: Children’s focus group reflections on mental health. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2022, 6, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, W.R.; Birdsey, N. Shyness, sensation seeking and birth-order position. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, L.C.; Coplan, R.J.; Bowker, A. Keeping it all inside: Shyness, internalizing coping strategies and socio-emotional adjustment in middle childhood. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H. The Relationship between Internet Addiction Disorder and Anxiety in Senior High School Students: An Analysis of Moderating Mediating Effect. Master’s Dissertation, Mudanjiang Normal University, Mudanjiang, China, 2021, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, H.B.; Wu, Y.Z.; Zeng, Y.F.; Peng, S.L.; Chen, S.L. A Research on the relationship between internet addiction disorder and personality characteristics. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 33, 210–212. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Gender Difference | Sibling Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | t | p | Non-Sibling | Sibling | t | p | |

| Shyness | 38.90 ± 9.472 | 37.19 ± 9.837 | −3.828 | <0.001 | 37.33 ± 9.855 | 38.38 ± 9.604 | −2.105 | 0.035 |

| PPC1 | 24.77 ± 9.609 | 24.89 ± 8.501 | 0.294 | 0.769 | 25.48 ± 9.012 | 24.58 ± 9.112 | 1.923 | 0.939 |

| PPC2 | 9.68 ± 5.079 | 9.72 ± 4.705 | 0.184 | 0.854 | 9.74 ± 4.955 | 9.68 ± 4.882 | 0.238 | 0.812 |

| PPC3 | 8.96 ± 3.552 | 8.64 ± 3.397 | −1.960 | 0.050 | 9.06 ± 3.562 | 8.71 ± 3.445 | 1.995 | 0.046 |

| SA | 42.19 ± 12.493 | 39.62 ± 13.033 | −4.335 | <0.001 | 40.43 ± 13.056 | 41.16 ± 12.720 | −1.111 | 0.267 |

| IA | 50.25 ± 14.812 | 47.73 ± 15.736 | −3.544 | <0.001 | 47.86 ± 15.348 | 49.50 ± 15.277 | −2.088 | 0.037 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PPC1 | — | |||||||

| 2 PPC2 | 0.718 ** | — | ||||||

| 3 PPC3 | 0.687 ** | 0.548 ** | — | |||||

| 4 Shyness | 0.154 ** | 0.180 ** | 0.128 ** | — | ||||

| 5 SA | 0.264 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.249 ** | 0.270 ** | — | |||

| 6 IA | 0.216 ** | 0.245 ** | 0.187 ** | 0.290 ** | 0.752 ** | — | ||

| 7 Age | −0.064 ** | −0.006 | −0.045 | 0.162 ** | 0.253 ** | 0.243 ** | — | |

| 8 Gender | −0.007 | −0.004 | 0.045 | 0.089 ** | 0.100 ** | 0.082 ** | 0.038 | — |

| Indirect Effect | β (Standardized Indirect Effect) | SE | p | 95% CI Standardized Indirect Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From shyness to smartphone addiction | ||||

| PPC1: | (0.174) × (0.285) = 0.049 | 0.009 | p < 0.001 | 0.031, 0.068 |

| PPC2: | (0.201) × (0.278) = 0.056 | 0.010 | p < 0.001 | 0.037, 0.075 |

| PPC3: | (0.131) × (0.294) = 0.039 | 0.010 | p < 0.001 | 0.019, 0.058 |

| From shyness to internet addiction | ||||

| PPC1: | (0.174) × (0.303) = 0.053 | 0.010 | p < 0.001 | 0.033, 0.072 |

| PPC2: | (0.201) × (0.292) = 0.059 | 0.010 | p < 0.001 | 0.039, 0.079 |

| PPC3: | (0.131) × (0.313) = 0.041 | 0.010 | p < 0.001 | 0.021, 0.061 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Ran, G.; Ren, J. Parental Psychological Control and Addiction Behaviors in Smartphone and Internet: The Mediating Role of Shyness among Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16702. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416702

Zhang Q, Ran G, Ren J. Parental Psychological Control and Addiction Behaviors in Smartphone and Internet: The Mediating Role of Shyness among Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16702. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416702

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qi, Guangming Ran, and Jing Ren. 2022. "Parental Psychological Control and Addiction Behaviors in Smartphone and Internet: The Mediating Role of Shyness among Adolescents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16702. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416702

APA StyleZhang, Q., Ran, G., & Ren, J. (2022). Parental Psychological Control and Addiction Behaviors in Smartphone and Internet: The Mediating Role of Shyness among Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16702. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416702