The Key Role of Psychosocial Competencies in Evidence-Based Youth Mental Health Promotion: Academic Support in Consolidating a National Strategy in France

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Specificity of the Field of Prevention and Mental Health Promotion

1.2. The Key Role of Psychosocial Competencies in the French National Strategical Orientation Planning of Prevention and Youth Mental Health Promotion: A Historical Perspective

2. Methods

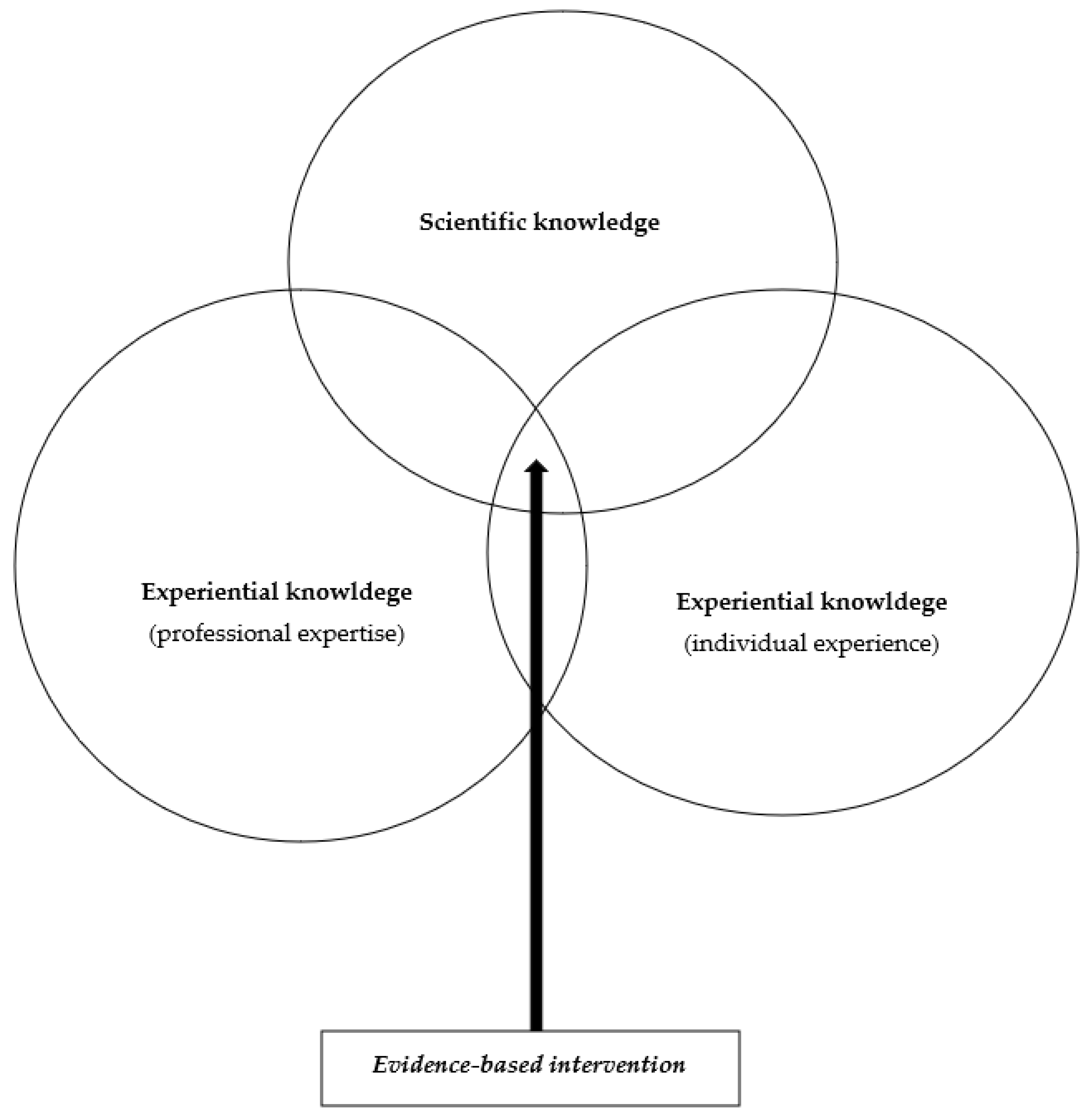

2.1. The EBM/EBPH Paradigm to Build the New French National Strategy

2.2. The new French National Strategy Based on Literature Reviews

- -

- The PSC intervention is structured and focused (set of activities organized and manualized).

- -

- The implementation of the CPS intervention is of high quality (quality of the training with clear explanation of mechanisms of action).

- -

- The PSC activities’ content is based on the scientific knowledge and evidence-based practices.

- -

- The PSC activities are intensive and long term.

- -

- PSC activities use experiential methods and are based on positive education principals.

3. Results

3.1. The Key Role of PSCs in Evidence-Based Programs for Prevention and Mental Health Promotion

3.2. The Key Role of PSCs in the Determinants of (Youth) Mental Health

3.3. Psychosocial Competencies: A New Definition and Classification for the French National Strategy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Division of Health Promotion, Education, and Communication, “Glossaire de la Promotion de la Santé”. World Health Organization. 1998. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67245/WHO_HPR_HEP_98.1_fre.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Prince, M.; Patel, V.; Saxena, S.; Maj, M.; Maselko, J.; Phillips, M.R.; Rahman, A. No health without mental health. Lancet 2007, 370, 859–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HCSP. Avis Relatif à L’impact du COVID-19 sur la Santé Mentale; HCSP: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice: Summary Report/a Report from the World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in Collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation and the University of Melbourne. World Health Organization, 2004a. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42940/9241591595.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- World Health Organization. Prevention of Mental Disorders: Effective Interventions and Policy Options: Summary Report/a Report of the World Health Organization Dept. of Mental Health and Substance Abuse; in collaboration with the Prevention Research Centre of the Universities of Nijmegen and Maastricht. World Health Organization, 2004b. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43027/924159215X_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Arango, C.; Díaz-Caneja, C.M.; McGorry, P.D.; Rapoport, J.; Sommer, I.E.; Vorstman, J.A.; McDaid, D.; Marín, O.; Serrano-Drozdowskyj, E.; Freedman, R.; et al. Preventive strategies for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Solidarity and Health/Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. “Stratégie Nationale de Santé 2018–2022. Priorité Prévention. Rester en Bonne Santé Tout au Long de sa vie.” Paris: Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. 2018. Available online: https://www.reseau-national-nutrition-sante.fr/UserFiles/File/s-informer/textes-de-reference/plan-priorite-prevention-sante-reseau-national-nutrition-sante.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Cléry-Melin, P.; Pascal, J.-C.; Kovess-Masféty, V. Plan d’actions pour le développement de la psychiatrie et la promotion de la santé mentale. Rev. Française Des Aff. Soc. 2004, 1, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantuelle, M.; Demeulemeester, R. Comportements à Risque et Santé: Agir en Milieu Scolaire. Programs et Stratégies Efficaces. Saint-Denis: Institut National de Prévention et d’éducation pour la Santé. 2008. Available online: http://ark.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41196510s (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Lamboy, B. Soutenir la parentalité: Pourquoi et comment ?: Différentes approches pour un même concept. Devenir 2009, 21, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Solidarity and Health/Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. “Feuille de Route Santé Mentale et Psychiatrie.” Ministry of Solidarity and Health/Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. 2018. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/prevention-en-sante/sante-mentale/Feuille-de-route-de-la-sante-mentale-et-de-la-psychiatrie-11179/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Leeman, J.; Birken, S.A.; Powell, B.J.; Rohweder, C.; Shea, C.M. Beyond ‘implementation strategies’: Classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotheram-Borus, M.J.; Swendeman, D.; Becker, K.D. Adapting Evidence-Based Interventions Using a Common Theory, Practices, and Principles. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2014, 43, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, B.; Beaulieu, M.-D. La médecine basée sur les données probantes ou médecine fondée sur des niveaux de preuve: De la pratique à l’enseignement. Pédagogie Médicale 2004, 5, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Geddes, J.R.; Game, D.; Jenkins, N.E.; Peterson, L.A.; Pottinger, G.R.; Sackett, D.L. What proportion of primary psychiatric interventions are based on evidence from randomised controlled trials? Qual. Saf. Health Care 1996, 5, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.J.; Tang, K.C.; Nutbeam, D. WHO Health Promotion Glossary: New terms. Health Promotion International 2006, 21, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambon, L.; Ridde, V.; Alla, F. Réflexions et perspectives concernant l’evidence-based health promotion dans le contexte français. Rev. D’épidémiologie Et De St. Publique 2010, 58, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohatsu, N.D.; Robinson, J.G.; Torner, J.C. Evidence-based public health. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 27, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Broucke, S. Theory-informed health promotion: Seeing the bigger picture by looking at the details. Health Promot. Int. 2012, 27, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jané-Llopis, E.; Barry, M.; Hosman, C.; Patel, V. Mental health promotion works: A review. Promot. Educ. 2005, 12, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamboy, B.; Clément, J.; Saïas, T.; Guillemont, J. Interventions validées en prévention et promotion de la santé mentale auprès des jeunes. Santé Publique 2012, 23, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamboy, B.; Guillemont, J. Développer les compétences psychosociales des enfants et des parents: Pourquoi et comment? Devenir 2015, 26, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health France/Santé Publique France. Les Compétences Psychosociales: Un Référentiel Pour un Déploiement Auprès des Enfants et des Jeunes. Synthèse de L’état des Connaissances Scientifiques et Théoriques Réalisé en 2021. Saint-Maurice: Santé Publique France, 2022a. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Public Health France/Santé Publique France. Les Compétences Psychosociales: État des Connaissances Scientifiques et théoriques. Saint-Maurice: Santé Publique France, 2022b. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- World Health Organization. Preventing Youth Violence: An Overview of the Evidence. World Health Organization. 2015. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/181008/9789241509251_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Taylor, R.D.; Schellinger, K.B. The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.C.; Taske, N.L.; Swann, C.; Waller, S. Public Health Interventions to Promote Positive Mental Health and Prevent Mental Health Disorders among Adults; NICE: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sklad, M.; Diekstra, R.; DE Ritter, M.; BEN, J.; Gravesteijn, C. Effectiveness of school-based universal social, emotional, and behavioral programs: Do they enhance students’ development in the area of skill, behavior, and adjustment? Psychol. Sch. 2012, 49, 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.A.; Dyson, J.; Cowdell, F.; Watson, R. Do universal school-based mental health promotion programmes improve the mental health and emotional wellbeing of young people? A literature review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 27, e412–e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sande, M.C.E.; Fekkes, M.; Kocken, P.L.; Diekstra, R.F.W.; Reis, R.; Gravesteijn, C. Do universal social and emotional learning programs for secondary school students enhance the competencies they address? A systematic review. Psychol. Sch. 2019, 56, 1545–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrovich, C.E.; Cortes, R.C.; Greenberg, M.T. Improving Young Children’s Social and Emotional Competence: A Randomized Trial of the Preschool “PATHS” Curriculum. J. Prim. Prev. 2007, 28, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieffe, C.; Oosterveld, P.; Miers, A.C.; Terwogt, M.M.; Ly, V. Emotion awareness and internalising symptoms in children and adolescents: The Emotion Awareness Questionnaire revised. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2008, 45, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J.; O’Brien, M.E. Self-Awareness and Constructive Functioning: Revisiting “the Human Dilemma”. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 23, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, N.; D’Amours, G.; Poissant, J.; Manseau, S. Avis Scientifique sur les Interventions Efficaces en Promotion de la Santé Mentale et en Prévention des Troubles Mentaux; INSPQ: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ICIS. Améliorer la Santé des Canadiens: Explorer la Santé Mentale Positive; Institut Canadien d’Information sur la Santé: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- INSERM (dir.). Troubles Mentaux. Dépistage et Prévention chez L’enfant et L’adolescent. Rapport; XXII-887; Les éditions Inserm: Paris, France, 2002; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10608/165 (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- McDonald, G.; O’Hara, K. Ten Elements of Mental Health, Its Promotion and Demotion: Implications for Practice. Society of Health Education and Health Promotion Specialists. In Making It Happen–A Guide to Delivering Mental Health Promotion; Department of Health: London, UK, 1998; Available online: http://www.mentalhealthpromotion.net/resources/makingithappen.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Orpana, H.; Vachon, J.; Dykxhoorn, J.; McRae, L.; Jayaraman, G. Monitoring positive mental health and its determinants in Canada: The development of the Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2016, 36, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabarkapa, S.; Nadjidai, S.E.; Murgier, J.; Ng, C.H. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: A rapid systematic review. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 8, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevance, A.; Gourion, D.; Hoertel, N.; Llorca, P.-M.; Thomas, P.; Bocher, R.; Moro, M.-R.; Laprévote, V.; Benyamina, A.; Fossati, P.; et al. Ensuring mental health care during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in France: A narrative review. L’encephale 2020, 46, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, J.; Prinstein, M.J.; Clark, L.A.; Rottenberg, J.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Albano, A.M.; Aldao, A.; Borelli, J.L.; Chung, T.; Davila, J.; et al. Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitzman, J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. Psychiatr. Polska 2020, 54, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, E.; Siegel, Z.; Pike, K.M. The Mental Health of Frontline Health Care Providers during Pandemics: A Rapid Review of the Literature. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, M.A.; Shanahan, L.; Rohde, J.; Schulz, A.; Wackerhagen, C.; Kobylińska, D.; Tuescher, O.; Binder, H.; Walter, H.; Kalisch, R.; et al. Standalone Smartphone Cognitive Behavioral Therapy–Based Ecological Momentary Interventions to Increase Mental Health: Narrative Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e19836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, J.; Yuan, K.; Gong, Y.; Meng, S.; Bao, Y.; Lu, L. Raising awareness of suicide prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2020, 40, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soklaridis, S.; Lin, E.; Lalani, Y.; Rodak, T.; Sockalingam, S. Mental health interventions and supports during COVID- 19 and other medical pandemics: A rapid systematic review of the evidence. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Departement of Education. Mental Health and Behaviour in Schools Departmental Advice for School Staff. UK Department of Education. 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1069687/Mental_health_and_behaviour_in_schools.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Juan, N.V.S.; Aceituno, D.; Djellouli, N.; Sumray, K.; Regenold, N.; Syversen, A.; Symmons, S.M.; Dowrick, A.; Mitchinson, L.; Singleton, G.; et al. Mental health and well-being of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: Contrasting guidelines with experiences in practice. BJPsych Open 2020, 7, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weich, S.; Patterson, J.; Shaw, R.; Stewart-Brown, S. Family relationships in childhood and common psychiatric disorders in later life: Systematic review of prospective studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 194, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, V.; Bolanos, J.F.; Fiallos, J.; Strand, S.E.; Morris, K.; Shahrokhinia, S.; Cushing, T.R.; Hopp, L.; Tiwari, A.; Hariri, R.; et al. COVID-19: Review of a 21st Century Pandemic from Etiology to Neuro-psychiatric Implications. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 77, 459–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Life Skills Education for Children and Adolescents in Schools, 2nd ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63552 (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- World Health Organization. Skills for Health: Skills-Based Health Education including Life Skills: An Important Component of a Child-Friendly/Health-Promoting School; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42818/924159103X.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Mangrulkar, L.; Whitman, C.V.; Posner, M. Life Skills Approach to Child and Adolescent Health Human Development; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payton, J.W.; Wardlaw, D.M.; Graczyk, P.A.; Bloodworth, M.R.; Tompsett, C.J.; Weissberg, R.P. Social and Emotional Learning: A Framework for Promoting Mental Health and Reducing Risk Behavior in Children and Youth. J. Sch. Health 2000, 70, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, T. CASEL’s Framework for Systemic Social and Emotional Learning. CASEL. 2019. Available online: https://measuringsel.casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/AWG-Framework-Series-B.2.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Kankaraš, M.; Suarez-Alvarez, J. Assessment framework of the OECD Study on Social and Emotional Skills. In OECD Educa-tion Working Papers; No. 207; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brunello, G.; Schlotter, M. Non-Cognitive Skills and Personality Traits: Labour Market Relevance and Their Development in Education & Training Systems; SSRN Journal. 2011. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1858066. (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Cinque, M.; Carretero, S.; Napierala, J. Non-Cognitive Skills and Other Related Concepts: Towards a Better Understanding of Similarities and Differences; JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology: Ispra, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD beyond Academic Learning. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/beyond-academic-learning_92a11084-en (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Akbar, M.B.; French, J.; Lawson, A. Critical review on social marketing planning approaches. Soc. Bus. 2019, 9, 361–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASEL. CASEL’S SEL Framework: What Are the Core Competences Areas and Where Are They Promoted? CASEL. 2020. Available online: https://casel.org/casel-sel-framework-11-2020/?view=true (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Lamboy, B. Les Compétences Psychosociales: Bien-être, Prévention, Education; UGA éditions PUG: Grenoble Fontaine, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia, J.F.; Rodriguez, G.I.; Guerra, N.G.; Bustamante, A.; Chaparro, M.P.; Castellanos, M. Step by Step: Teacher’s Guide—Eleventh Grade (English). Social and Emotional Learning Program; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/721231527282872141/Teacher-s-Guide-Eleventh-Grade (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- UNICEF. Comprehensive Life Skills Framework. New Delhi: UNICEF. 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/india/media/2571/file/Comprehensive-lifeskills-framework.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- World Health Organization. Preventing Violence by Developing Life skills in Children and Adolescents. World Health Organization. 2009. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44089/9789241597838_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Wigelsworth, M.; Verity, L.; Mason, C.; Qualter, P.; Humphrey, N. Social and emotional learning in primary schools: A review of the current state of evidence. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 92, 898–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French Government. Une Ambition Refondée Pour la Santé Mentale et la Psychiatrie en France—Assises de la Santé Mentale et de la Psychiatrie, Septembre 2021. French Government. 2022. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/dp_sante_mentale-ok_01.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Ministry of Solidarity and Health/Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. Bulletin Officiel. Santé, Protection Sociale, Solidarité, n°18, Pages 83–101. Ministry of Solidarity and Health/Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. 2022. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/fichiers/bo/2022/2022.18.sante.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2022).

| Risk Factors | Protection Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual factors | Biological |

|

|

| Cognitive |

|

| |

| Emotional and social |

|

| |

| Life events |

|

| |

| Relational and family factors | Parent-child relations |

|

|

| Mental health of parents |

| ||

| Family climate and events |

|

| |

| Relations with peers and friends |

|

| |

| Environmental factors | Social, economic and cultural |

|

|

| Physical environment |

|

| |

| Categories | General Competences | Specific Competences |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive competencies | Self-awareness | Self-knowledge (strengths and weaknesses, goals, values, internal discourse...) |

| Critical thinking skills (identification of biases, influences...) | ||

| Positive self-evaluation | ||

| Mindful awareness of inner experiences | ||

| Self-regulation | Impulsivity management | |

| Goal achievement skills (definition, planning...) | ||

| Constructive decision-making | Ability to make responsible choices | |

| Ability to solve problems creatively | ||

| Emotion and stress awareness | Understanding emotions and stress | |

| Identifying one’s emotions and stress | ||

| Emotion regulation | Expressing one’s emotions in a positive way | |

| Emotional competences | ||

| Managing one’s emotions (including difficult emotions: anger, anxiety, sadness...) | ||

| Stress management | Regulating one’s stress in daily life | |

| Ability to cope with adversity | ||

| Positive communication | Empathetic listening skills | |

| Effective communication (valuing, clear expression...) | ||

| Positive relationships | Developing social bonds skills (reaching out, making connections, building friendships, etc.) | |

| Social comptences | ||

| Prosocial attitudes and behaviors (acceptance, collaboration, cooperation, mutual support...) | ||

| Problem-solving | Ability to ask for help | |

| Ability to be assertive and to say no | ||

| Ability to resolve conflicts in a constructive way |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lamboy, B.; Beck, F.; Tessier, D.; Williamson, M.-O.; Fréry, N.; Turgon, R.; Tassie, J.-M.; Barrois, J.; Bessa, Z.; Shankland, R. The Key Role of Psychosocial Competencies in Evidence-Based Youth Mental Health Promotion: Academic Support in Consolidating a National Strategy in France. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416641

Lamboy B, Beck F, Tessier D, Williamson M-O, Fréry N, Turgon R, Tassie J-M, Barrois J, Bessa Z, Shankland R. The Key Role of Psychosocial Competencies in Evidence-Based Youth Mental Health Promotion: Academic Support in Consolidating a National Strategy in France. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416641

Chicago/Turabian StyleLamboy, Béatrice, François Beck, Damien Tessier, Marie-Odile Williamson, Nadine Fréry, Roxane Turgon, Jean-Michel Tassie, Julie Barrois, Zinna Bessa, and Rebecca Shankland. 2022. "The Key Role of Psychosocial Competencies in Evidence-Based Youth Mental Health Promotion: Academic Support in Consolidating a National Strategy in France" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416641

APA StyleLamboy, B., Beck, F., Tessier, D., Williamson, M.-O., Fréry, N., Turgon, R., Tassie, J.-M., Barrois, J., Bessa, Z., & Shankland, R. (2022). The Key Role of Psychosocial Competencies in Evidence-Based Youth Mental Health Promotion: Academic Support in Consolidating a National Strategy in France. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416641