Social and Emotional Loneliness in Older Community Dwelling-Individuals: The Role of Socio-Demographics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Study and Population

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Information Collection Procedure

Evaluation of Emotional and Social Loneliness

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Subjects

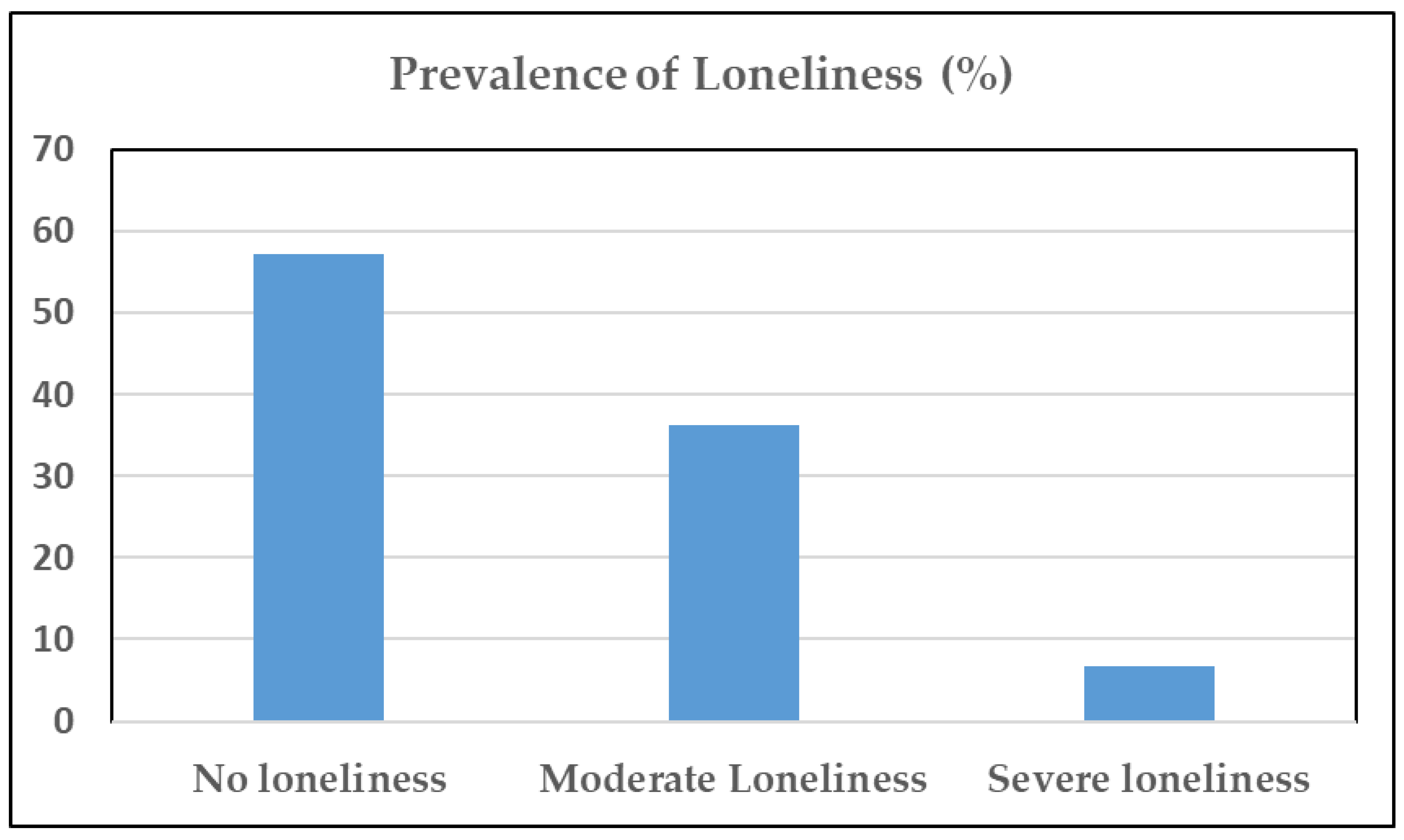

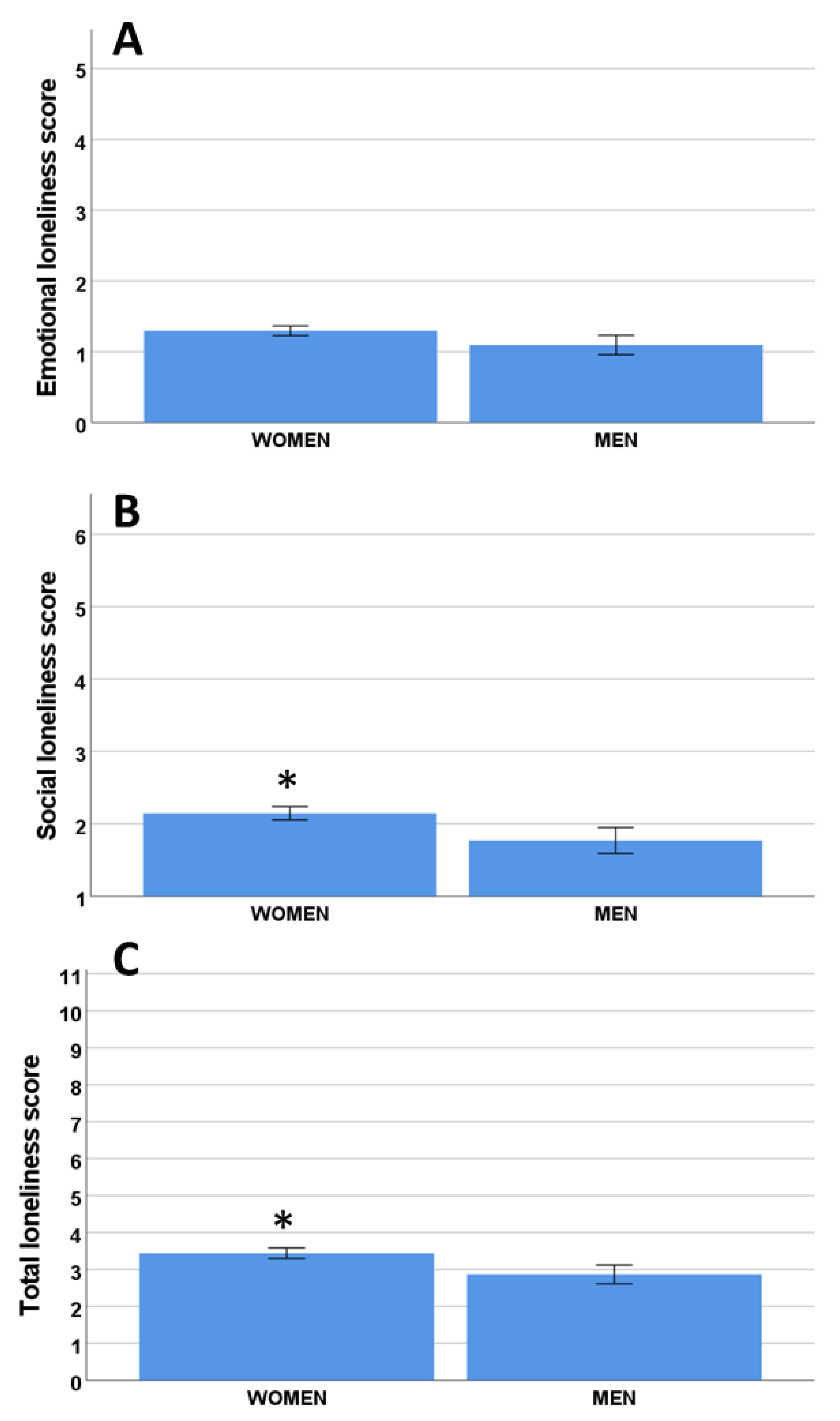

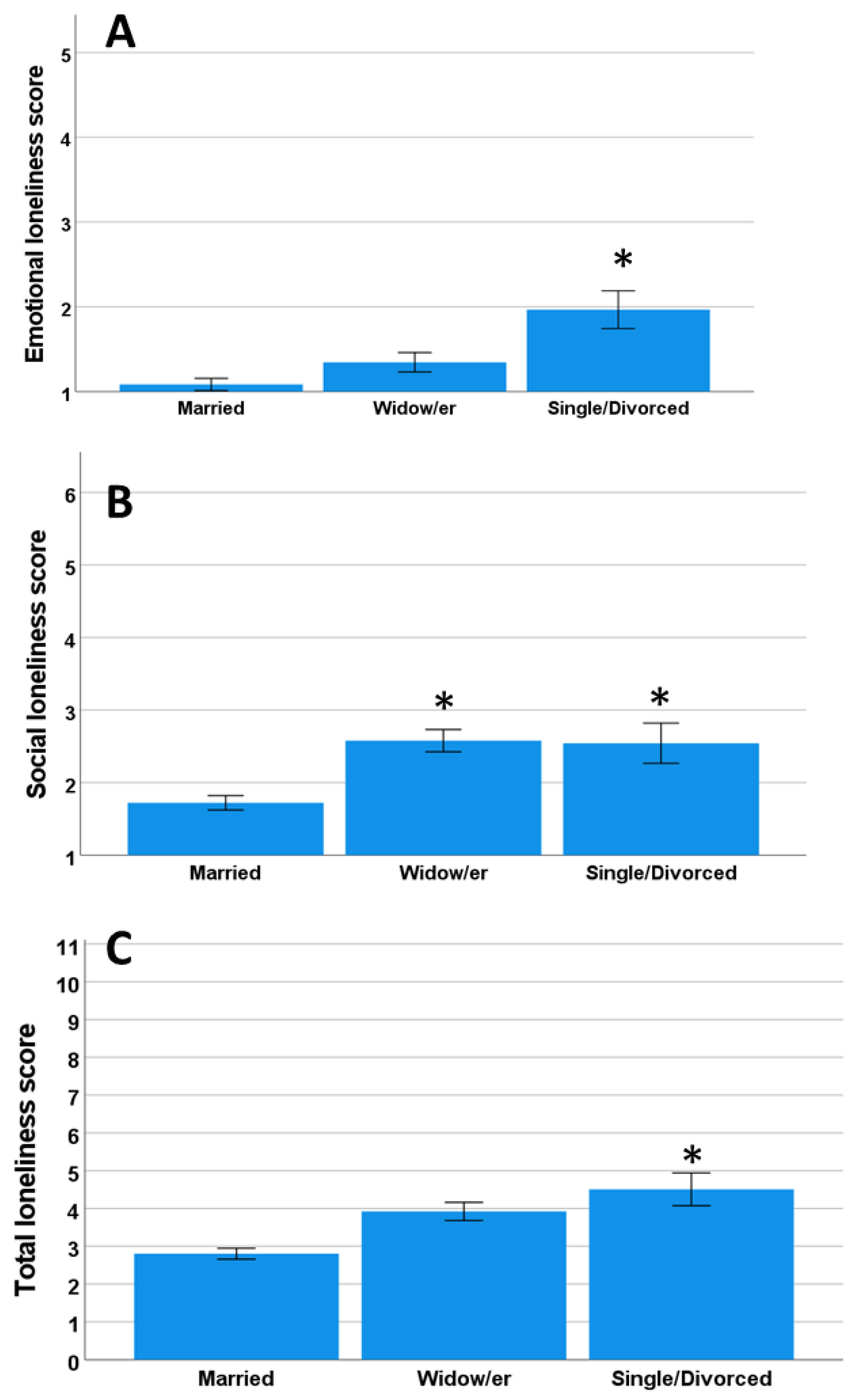

3.2. Evaluation of Loneliness and Socio-Demographics

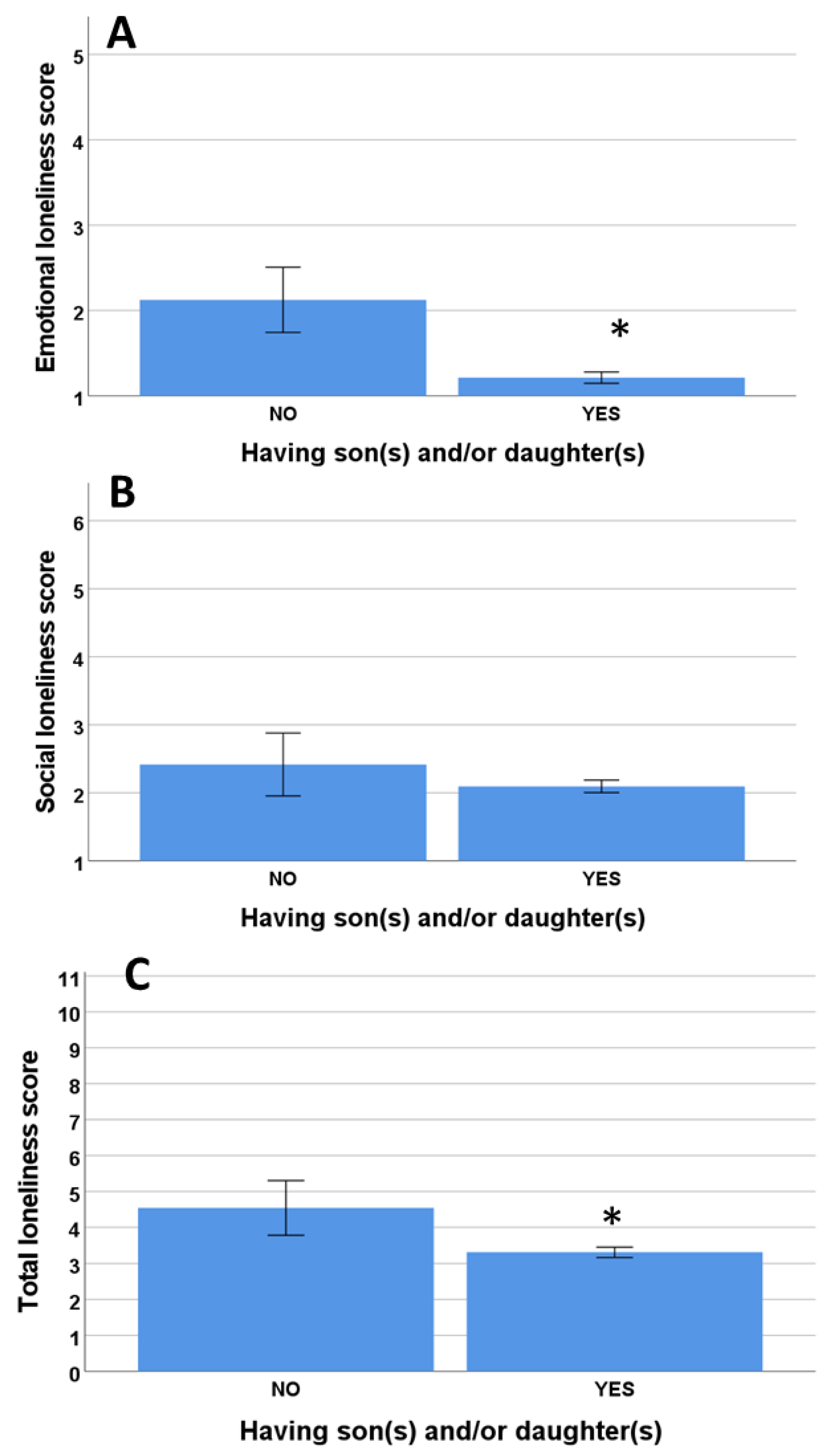

3.3. Influence of the Presence of Relatives

3.4. Loneliness and Impact of Ambulation and Architectonic Barriers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foreman, K.J.; Marquez, N.; Dolgert, A.; Fukutaki, K.; Fullman, N.; McGaughey, M.; Pletcher, M.A.; Smith, A.E.; Tang, K.; Yuan, C.-W.; et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-Cause and cause-Specific mortality for 250 causes of death: Reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 2018, 392, 2052–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ausín, B.; Muñoz, M.; Castellanos, M.A. Loneliness, Sociodemographic and Mental Health Variables in Spanish Adults over 65 Years Old. Span. J. Psychol. 2017, 20, E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gierveld, J.D.J. A review of loneliness: Concept and definitions, determinants and consequences. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 1998, 8, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, N.K.; Kanaan, M.; Gilbody, S.; Ronzi, S.; Hanratty, B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart 2016, 102, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, R.S. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet 2018, 391, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, C.R.; Bowling, A. A Longitudinal Analysis of Loneliness among Older People in Great Britain. J. Psychol. 2012, 146, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luanaigh, C.Ó.; Lawlor, B.A. Loneliness and the health of older people. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 23, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, A.D.; Uchino, B.N.; Wethington, E. Loneliness and Health in Older Adults: A Mini-Review and Synthesis. Gerontology 2015, 62, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtin, E.; Knapp, M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holwerda, T.J.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Beekman, A.T.F.; van Tilburg, T.; Stek, M.L.; Jonker, C.; Schoevers, R.A. Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: Results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2014, 85, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, J.M.; Pinazo-Hernandis, S.; Oliver, A.; Donio-Bellegarde, M.; Tomás-Aguirre, F. Loneliness and social support: Differential predictive power on depression and satisfaction in senior citizens. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 47, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campagne, D.M. Stress and perceived social isolation (loneliness). Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 82, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Thisted, R.A.; Masi, C.M.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychol. Aging 2010, 25, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Barnes, L.L.; Bennett, D.A.; Li, Y.; Bienias, J.L.; De Leon, C.F.M.; Evans, D.A. Proneness to psychological distress and risk of Alzheimer disease in a biracial community. Neurology 2005, 64, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.S.; Krueger, K.R.; Arnold, S.E.; Schneider, J.A.; Kelly, J.F.; Barnes, L.L.; Tang, Y.; Bennett, D.A. Loneliness and Risk of Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Thisted, R.A. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol. Aging 2006, 21, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Lara, E.; Rubio-Valera, M.; Olaya, B.; Moneta, M.V.; Rico-Uribe, L.A.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Mundó, J.; Haro, J.M. Loneliness and depression in the elderly: The role of social network. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzen, E.; Çikrikci. The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Masi, C.M.; Thisted, R.A.; Cacioppo, J.T. From Social Structural Factors to Perceptions of Relationship Quality and Loneliness: The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Journals Gerontol. Ser. B 2008, 63, S375–S384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, A.; Nicolle, J. Social Isolation and Loneliness: The New Geriatric Giants: Approach for Primary Care. Can. Fam. Physician Med. Fam. Can. 2020, 66, 176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Fierloos, I.N.; Tan, S.S.; Williams, G.; Alhambra-Borrás, T.; Koppelaar, E.; Bilajac, L.; Verma, A.; Markaki, A.; Mattace-Raso, F.; Vasiljev, V.; et al. Socio-demographic characteristics associated with emotional and social loneliness among older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagan, R. Gender and Age Differences in Loneliness: Evidence for People without and with Disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Gadbois, E.; Jimenez, F.; Brazier, J.F.; Davoodi, N.M.; Nunn, A.S.; Mills, W.L.; Dosa, D.; Thomas, K.S. Findings from Talking Tech: A Technology Training Pilot Intervention to Reduce Loneliness and Social Isolation among Homebound Older Adults. Innov. Aging 2022, 6, igac040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlomann, A.; Seifert, A.; Zank, S.; Woopen, C.; Rietz, C. Use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Devices Among the Oldest-Old: Loneliness, Anomie, and Autonomy. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, igz050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jong Gierveld, J.; Van Tilburg, T. The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: Tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur. J. Ageing 2010, 7, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buz, J.; Pérez-Arechaederra, D. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of the Spanish version of the 11-item De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buz, J.; Prieto, G. Análisis de la Escala de Soledad de De Jong Gierveld mediante el modelo de Rasch. Univ. Psychol. 2013, 12, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Frades-Payo, B.; Forjaz, M.J.; Martínez-Martín, P.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Rojo-Pérez, F. Propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario de Apoyo Social Funcional y de la Escala de Soledad en adultos mayores no institucionalizados en España. Gac. Sanit. 2012, 26, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gené-Badia, J.; Comice, P.; Belchín, A.; Erdozain, M.; Cáliz, L.; Torres, S.; Rodríguez, R. Perfiles de soledad y aislamiento social en población urbana. Atención primaria 2019, 52, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaya, B.; Domènech-Abella, J.; Moneta, M.V.; Lara, E.; Caballero, F.F.; Rico-Uribe, L.A.; Haro, J.M. All-cause mortality and multimorbidity in older adults: The role of social support and loneliness. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 99, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncero, U.M.; González-Rábago, Y. Soledad no deseada, salud y desigualdades sociales a lo largo del ciclo vital. Gac. Sanit. 2020, 35, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mas, M.; Mesquida, M.M.; Miralles, R.; Soldevila, L.; Prat, N.; Bonet-Simó, J.M.; Isnard, M.; Izquierdo, M.E.; Sanchez, I.G.; Noguerola, S.R.; et al. Clinical factors related to COVID-19 outcomes in institutionalized older adults: Cross-sectional analysis from a cohort in Catalonia. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1857–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, M.E.; Klein, E.M.; Brähler, E.; Reiner, I.; Jünger, C.; Michal, M.; Wiltink, J.; Wild, P.S.; Münzel, T.; Lackner, K.J.; et al. Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-María, N.; Caballero, F.F.; Miret, M.; Tyrovolas, S.; Haro, J.M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Chatterji, S. Differential impact of transient and chronic loneliness on health status. A longitudinal study. Psychol. Health 2019, 35, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, C.R.; Mõttus, R.; Deary, I.J.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A. Personality and Risk of Frailty: The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Ann. Behav. Med. 2016, 51, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Yap, C.W.; Heng, B.H. Associations of social isolation, social participation, and loneliness with frailty in older adults in Singapore: A panel data analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, F.; Béland, F. Frailty as a Moderator of the Relationship between Social Isolation and Health Outcomes in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van As, B.A.L.; Imbimbo, E.; Franceschi, A.; Menesini, E.; Nocentini, A. The longitudinal association between loneliness and depressive symptoms in the elderly: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 34, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Sorensen, S. Influences on Loneliness in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 23, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernova, A.; Frajo-Apor, B.; Pardeller, S.; Tutzer, F.; Plattner, B.; Haring, C.; Holzner, B.; Kemmler, G.; Marksteiner, J.; Miller, C.; et al. The Mediating Role of Resilience and Extraversion on Psychological Distress and Loneliness Among the General Population of Tyrol, Austria Between the First and the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 766261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, B.N.; Rook, K.S. Emotions, relationships, health and illness into old age. Maturitas 2020, 139, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiao, C.; Lin, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-H.; Yi, C.-C. Loneliness in older parents: Marital transitions, family and social connections, and separate bedrooms for sleep. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancampfort, D.; Lara, E.; Smith, L.; Rosenbaum, S.; Firth, J.; Stubbs, B.; Hallgren, M.; Koyanagi, A. Physical activity and loneliness among adults aged 50 years or older in six low- and middle-income countries. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrempft, S.; Jackowska, M.; Hamer, M.; Steptoe, A. Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; McMunn, A.; Demakakos, P.; Hamer, M.; Steptoe, A. Social isolation and loneliness: Prospective associations with functional status in older adults. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tough, H.; Gross-Hemmi, M.; Stringhini, S.; Eriks-Hoogland, I.; Fekete, C. Who is at Risk of Loneliness? A Cross-sectional Recursive Partitioning Approach in a Population-based Cohort of Persons with Spinal Cord Injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 103, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, F.; Baez, M.; Cernuzzi, L.; Casati, F. A Systematic Review on Technology-Supported Interventions to Improve Old-Age Social Wellbeing: Loneliness, Social Isolation, and Connectedness. J. Healthc. Eng. 2020, 2020, 2036842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Size | 530 participants |

| Mean Age (Range) | 72.7 ± 0.3 (56–102 years) |

| Nationality | 97% Spaniards |

| Educational Level | 66% primary education, 44% higher education |

| Number of Individuals Living with the Participant (Range) | 1.5 ± 0.04 (0–8 people) |

| Sons/Daughters (Percentage/Range) | 81.3% had son(s) and/or daughter(s) Mean 2.2 ± 0.6 (range 0–5) |

| Grandchildren (Percentage/Range) | 71.5% had grandchildren Mean 2.8 ± 0.1 (0–12 grandchildren) |

| Siblings (Percentage/Range) | 68.1% had siblings Mean 2.2 ± 0.1 (0–9 siblings) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibáñez-del Valle, V.; Corchón, S.; Zaharia, G.; Cauli, O. Social and Emotional Loneliness in Older Community Dwelling-Individuals: The Role of Socio-Demographics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416622

Ibáñez-del Valle V, Corchón S, Zaharia G, Cauli O. Social and Emotional Loneliness in Older Community Dwelling-Individuals: The Role of Socio-Demographics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416622

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbáñez-del Valle, Vanessa, Silvia Corchón, Georgiana Zaharia, and Omar Cauli. 2022. "Social and Emotional Loneliness in Older Community Dwelling-Individuals: The Role of Socio-Demographics" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416622

APA StyleIbáñez-del Valle, V., Corchón, S., Zaharia, G., & Cauli, O. (2022). Social and Emotional Loneliness in Older Community Dwelling-Individuals: The Role of Socio-Demographics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416622