Fresh Shelves, Healthy Pantries: A Pilot Intervention Trial in Baltimore City Food Pantries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Study Procedures

2.3.1. Policy Changes

2.3.2. Staff Education and Engagement

2.3.3. Client Education and Environmental Change

2.4. Instruments

2.4.1. Food Pantry Environmental Checklist (FPEC)

2.4.2. Client Questionnaire

2.4.3. Interventionist Form

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Food Stocking Variety Scores

2.5.2. Food Assortment Scoring Tool (FAST)

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

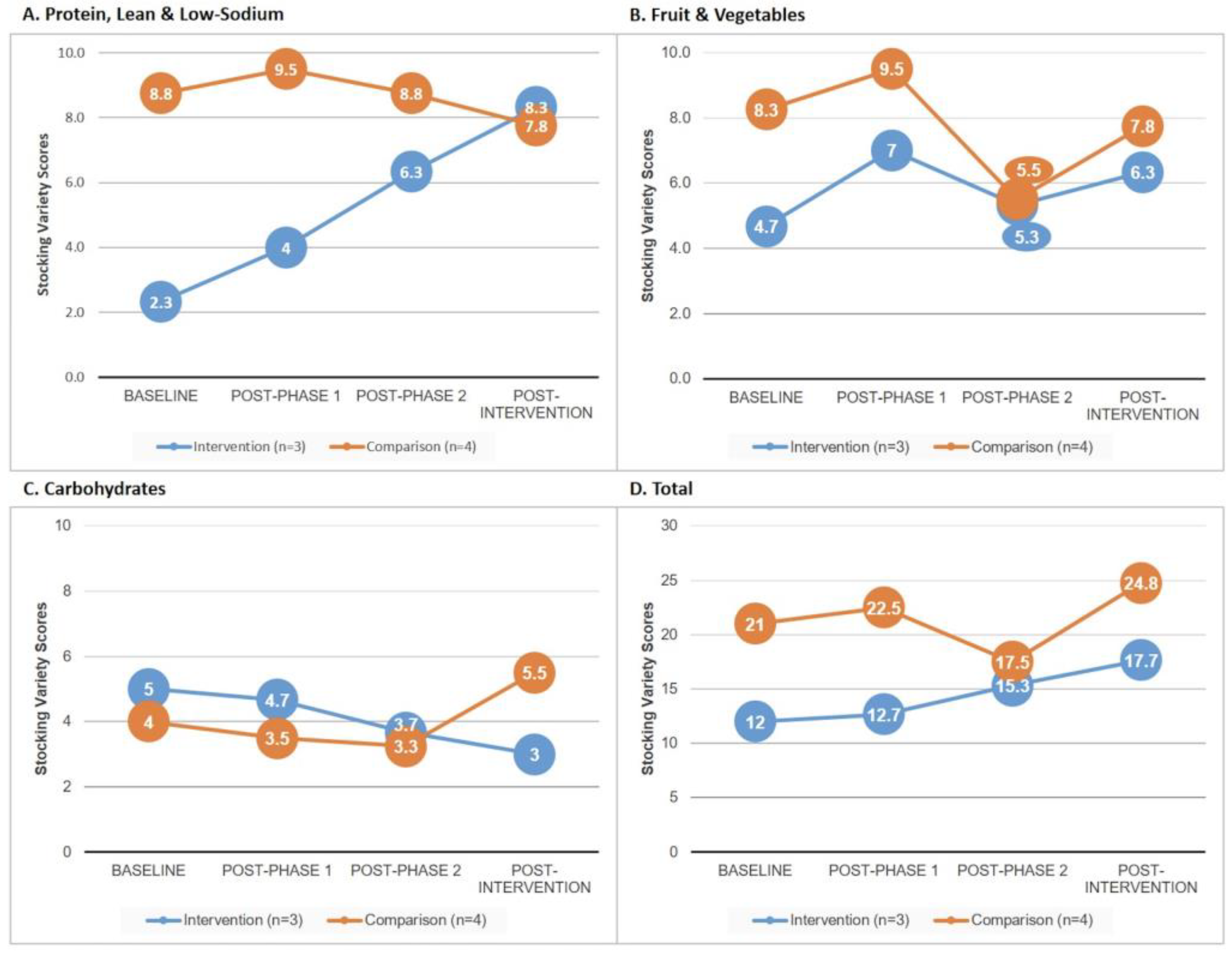

3.1. Food Stocking Variety (Research Question 1)

3.2. Healthfulness of Client Bags: FAST Scores (Research Question 2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weinfield, N.S.; Mills, G.; Borger, C.; Gearing, M.; Macaluso, T.; Montaquila, J.; Zedlewski, S. Hunger in America 2014: A report on charitable food distribution in the United States in 2013. Feed. Am. 2014, 44. Available online: https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/hunger-in-america-2014-full-report.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Kicinski, L.R. Characteristics of Short and Long-Term Food Pantry Users. Mich. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 26, 58–74. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, K.S.; Colantonio, A.G.; Picho, K.; Boyle, K.E. Self-efficacy is associated with increased food security in novel food pantry program. SSM Popul. Health 2016, 2, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapnick, M.; Barnidge, E.; Sawicki, M.; Elliott, M. Healthy Options in Food Pantries—Qualitative Analysis of Factors Affecting the Provision of Healthy Food Items in St. Louis, Missouri. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2019, 14, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, Z.A.; Bryan, A.D.; Rubinstein, E.B.; Frankel, H.J.; Maroko, A.R.; Schechter, C.B.; Stowers, K.C.; Lucan, S.C. Unreliable and Difficult-to-Access Food for Those in Need: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study of Urban Food Pantries. J. Community Health 2019, 44, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.; Hudson, H.; Webb, K.; Crawford, P.B. Food Preferences of Users of the Emergency Food System. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2011, 6, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.C.; Ross, M.; Webb, K.L. Improving the Nutritional Quality of Emergency Food: A Study of Food Bank Organizational Culture, Capacity, and Practices. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2013, 8, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Companion, M. Constriction in the Variety of Urban Food Pantry Donations by Private Individuals. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 32, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cureton, C.; King, R.P.; Warren, C.; Grannon, K.Y.; Hoolihan, C.; Janowiec, M.; Nanney, M.S. Factors associated with the healthfulness of food shelf orders. Food Policy 2017, 71, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, A.; Krummel, D.A.; Lee, S.Y. Availability of Food Options and Nutrition Education in Local Food Pantries. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, C.E.; Canterbury, M.; Carlson, S.; Bain, J.; Bohen, L.; Grannon, K.; Peterson, H.; Kottke, T. A behavioural economics approach to improving healthy food selection among food pantry clients. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2303–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabow, K.N.; Schumacher, J.; Banning, J.; Barnes, J.L. Highlighting Healthy Options in a Food Pantry Setting: A Pilot Study. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 48, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Shen, J.; Loehmer, E.; McCaffrey, J. A systematic review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1704–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eicher-Miller, H.A. A review of the food security, diet and health outcomes of food pantry clients and the potential for their improvement through food pantry interventions in the United States. Physiol. Behav. 2020, 220, 112871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Story, M.; Kaphingst, K.M.; Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Glanz, K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: Policy and environmental approaches. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Lee-Kwan, S.H.; Batorsky, B. Community-based interventions in prepared-food sources: A systematic review. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013, 10, E180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honeycutt, S.; Leeman, J.; McCarthy, W.J.; Bastani, R.; Carter-Edwards, L.; Clark, H.; Garney, W.; Gustat, J.; Hites, L.; Nothwehr, F.; et al. Evaluating Policy, Systems, and Environmental Change Interventions: Lessons Learned From CDC’s Prevention Research Centers. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, E174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoie-Roskos, M.R.; DeWitt, K.; Coombs, C. Changes in Nutrition Education: A Policy, Systems, and Environmental Approach. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, C.E.; Davey, C.; Friebur, R.; Nanney, M.S. Results of a Pilot Intervention in Food Shelves to Improve Healthy Eating and Cooking Skills Among Adults Experiencing Food Insecurity. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2017, 12, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.L.W.; Just, D.R.; Swigert, J.; Wansink, B. Food pantry selection solutions: A randomized controlled trial in client-choice food pantries to nudge clients to targeted foods. J. Public Health 2017, 39, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.S.; Wu, R.; Wolff, M.; Colantonio, A.G.; Grady, J. A novel food pantry program: Food security, self-sufficiency, and diet-quality outcomes. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 45, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood, NJ, USA, 1986; Available online: http://www.esludwig.com/uploads/2/6/1/0/26105457/bandura_sociallearningtheory.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Yan, S.; Caspi, C.; Trude, A.C.B.; Gunen, B.; Gittelsohn, J. How Urban Food Pantries are Stocked and Food Is Distributed: Food Pantry Manager Perspectives from Baltimore. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2020, 15, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akron-Canton Regional Foodbank. Client Choice Pantry Handbook; Akron-Canton Regional Foodbank: Akron, OH, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.H.; Gu, Y.; Yan, S.; Craig, H.C.; Adams, L.; Poirier, L.; Park, R.; Gunen, B.; Gittelsohn, J. Healthy Mondays or Sundays? Weekday Preferences for Healthy Eating and Cooking among a Food Insecure Population in a U.S. Urban Environment. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2020, 17, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, C.E.; Grannon, K.Y.; Wang, Q.; Nanney, M.S.; King, R.P. Refining and implementing the Food Assortment Scoring Tool (FAST) in food pantries. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 2548–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmet, A.; Depa, J.; Tinnemann, P.; Stroebele-Benschop, N. The Nutritional Quality of Food Provided from Food Pantries: A Systematic Review of Existing Literature. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2017, 117, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmet, A.; Depa, J.; Tinnemann, P.; Stroebele-Benschop, N. The Dietary Quality of Food Pantry Users: A Systematic Review of Existing Literature. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2017, 117, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffat, T.; Mohammed, C.; Newbold, K.B. Cultural Dimensions of Food Insecurity among Immigrants and Refugees. Human Organ. 2017, 76, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiehne, E.; Mendoza, N.S. Migrant and Seasonal Farmworker Food Insecurity: Prevalence, Impact, Risk Factors, and Coping Strategies. Soc. Work Public Health 2015, 30, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeldt, T. How CARES of Farmington Hills, Michigan, responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Agric Food Syst. Community Dev. 2020, 10, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Lewis, E.C.; Martin, N.M.; Zhu, S.; Poirier, L.; Van Dongen, E.J.I.; Ross, A.; Sundermeir, S.M.; Labrique, A.B.; Reznar, M.M.; et al. The Baltimore Urban Food Distribution (BUD) App: Study Protocol to Assess the Feasibility of a Food Systems Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.M.; Sundermeir, S.M.; Barnett, D.J.; van Dongen, E.J.I.; Rosman, L.; Rosenblum, A.J.; Gittelsohn, J. Digital Strategies to Improve Food Assistance in Disasters: A Scoping Review. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intervention Phase (Focus) | Food Pantry Staff Capacity Building (In-Person Training) | Educational/ Environmental Strategies | Policy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Lean, Low-Sodium Proteins | Benefits of lean, low-sodium proteins; procurement; nudging strategies; product placement. | Posters; Healthy alternatives displayed at eye-level near the entrance and posters. | Minimum depth-of-stock (minimum amount and variety per client). |

| 2: Fresh, Frozen and Canned Produce | Benefits of produce; food safety; prevention of waste; client education; positive messaging. | Recipe cards with tips on use in daily cooking; Placement at the entrance. | Minimum depth-of stock (minimum amount and variety per client). |

| 3: Healthy Carbohydrates | Consequences of high sugar consumption; benefits of whole grains; communication strategies for donors; community outreach. | Stoplight shelf labels for sugar and fiber content; Posters promoting low-sugar and whole grain items. | Restriction of high-sugar food and beverages (>10 g/serving) in procurement and stocking |

| Characteristic | Intervention (n = 3) | Comparison (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|

| Weight of food distributed annually (lbs), mean ± SD | 32,558.33 ± 43,264.34 | 60,114.25 ± 69,936.90 |

| Food sources, % | ||

| Maryland Food Bank | 71 | 43 |

| Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) | 14 | 19 |

| Partner churches | 0 | 24 |

| Private donations | 12 | 6 |

| Other (incl. food retailers, wholesalers) | 3 | 8 |

| Number of clients served in past 2 weeks, mean ± SD | 52.00 ± 30.00 | 126.00 ± 79.00 |

| Number of volunteer hours in past 2 weeks, mean ± SD | 50.00 ± 36.06 | 107.50 ± 99.15 |

| Number of hours of weekly food distribution, mean ± SD | 6.33 ± 2.08 | 6.00 ± 4.32 |

| Baseline | Mid-Point, After Phase 2 | Post-Intervention, After Phase 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 34) | Comparison (n = 41) | Intervention (n = 33) | Comparison (n = 48) | Intervention (n = 34) | Comparison (n = 40) | |

| Frequency of food pantry use, n (%) | ||||||

| Once a week or more often | 10 (29) | 9 (22) | 13 (38) | 15 (31) | 9 (26) | 13 (28) |

| Twice a month | 8 (24) | 10 (24) | 5 (15) | 8 (17) | 6 (18) | 6 (13) |

| Once a month | 9 (26) | 17 (41) | 14 (42) | 22 (46) | 14 (41) | 22 (47) |

| Once every other month | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 4 (9) |

| Less often than once every other month | 3 (9) | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Other | 2 (6) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | 1 (2) |

| Age, mean ± SD | 60.86 ± 15.46 a | 53.37 ± 12.85 a | 62.82 ± 15.97 b | 49.48 ± 13.85 b | 66.47 ± 13.33 c | 55.27 ± 15.41 c |

| Sex, % Female, n (%) | 28 (82) d | 14 (34) d | 26 (79) | 32 (67) | 27 (79) | 33 (70) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) Black/African American | 32 (94) | 36 (88) | 31 (94) | 37 (77) | 33 (97) | 41 (87) |

| Household size, mean ± SD | 3.09 ± 1.48 | 2.66 ± 1.77 | 2.70 ± 1.36 | 3.63 ± 2.51 | 2.71 ± 1.45 | 2.64 ± 1.81 |

| Number of children under age 18 in household, mean ± SD | 0.91 ± 1.1 | 0.93 ± 1.54 | 0.70 ± 1.26 | 1.46 ± 2.14 | 0.82 ± 1.42 | 1.0 ± 1.44 |

| SNAP recipients, n (%) | 17 (50) | 26 (63) | 15 (46) e | 37 (77) e | 11 (32) | 32 (68) |

| WIC recipients, n (%) | 4 (12) | 1 (2) | 5 (15) | 7 (15) | 3 (9) | 4 (9) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||||

| Employed 30+ h/wk | 8 (24) f | 0 (0) f | 3 (9) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | 1 (2) |

| Employed <30 h/wk | 4 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 3 (6) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Unemployed | 4 (12) | 11 (27) | 1(3) g | 30 (63) g | 11 (32) | 22 (47) |

| Retired | 11 (32) | 9 (22) | 19 (58) h | 5 (10) h | 15 (44) | 2 (4) |

| Disabled | 7 (21) i | 20 (49) i | 9 (27) | 9 (19) | 4 (12) | 19 (40) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Intervention | Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Interquartile Range | Median | Interquartile Range | |

| Baseline | 57.84 a,e,f | 11.13 | 69.72 a,c | 8.98 |

| (n = 34) | (n = 41) | |||

| Mid-Point–After Phase 2 | 66.32 e | 10.39 | 67.26 d | 12.06 |

| (n = 33) | (n = 48) | |||

| Post-Intervention–After Phase 3 | 67.57 b,f | 22.78 | 58.36 b,c,d | 14.24 |

| (n = 34) | (n = 40) | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gunen, B.; Reznar, M.M.; Yan, S.; Poirier, L.; Katragadda, N.; Ali, S.H.; Sundermeir, S.M.; Gittelsohn, J. Fresh Shelves, Healthy Pantries: A Pilot Intervention Trial in Baltimore City Food Pantries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315740

Gunen B, Reznar MM, Yan S, Poirier L, Katragadda N, Ali SH, Sundermeir SM, Gittelsohn J. Fresh Shelves, Healthy Pantries: A Pilot Intervention Trial in Baltimore City Food Pantries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315740

Chicago/Turabian StyleGunen, Bengucan, Melissa M. Reznar, Sally Yan, Lisa Poirier, Nathan Katragadda, Shahmir H. Ali, Samantha M. Sundermeir, and Joel Gittelsohn. 2022. "Fresh Shelves, Healthy Pantries: A Pilot Intervention Trial in Baltimore City Food Pantries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315740

APA StyleGunen, B., Reznar, M. M., Yan, S., Poirier, L., Katragadda, N., Ali, S. H., Sundermeir, S. M., & Gittelsohn, J. (2022). Fresh Shelves, Healthy Pantries: A Pilot Intervention Trial in Baltimore City Food Pantries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315740