Physicians’ Perspectives Regarding Private Equity Transactions in Outpatient Health Care—A Scoping Review and Qualitative Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

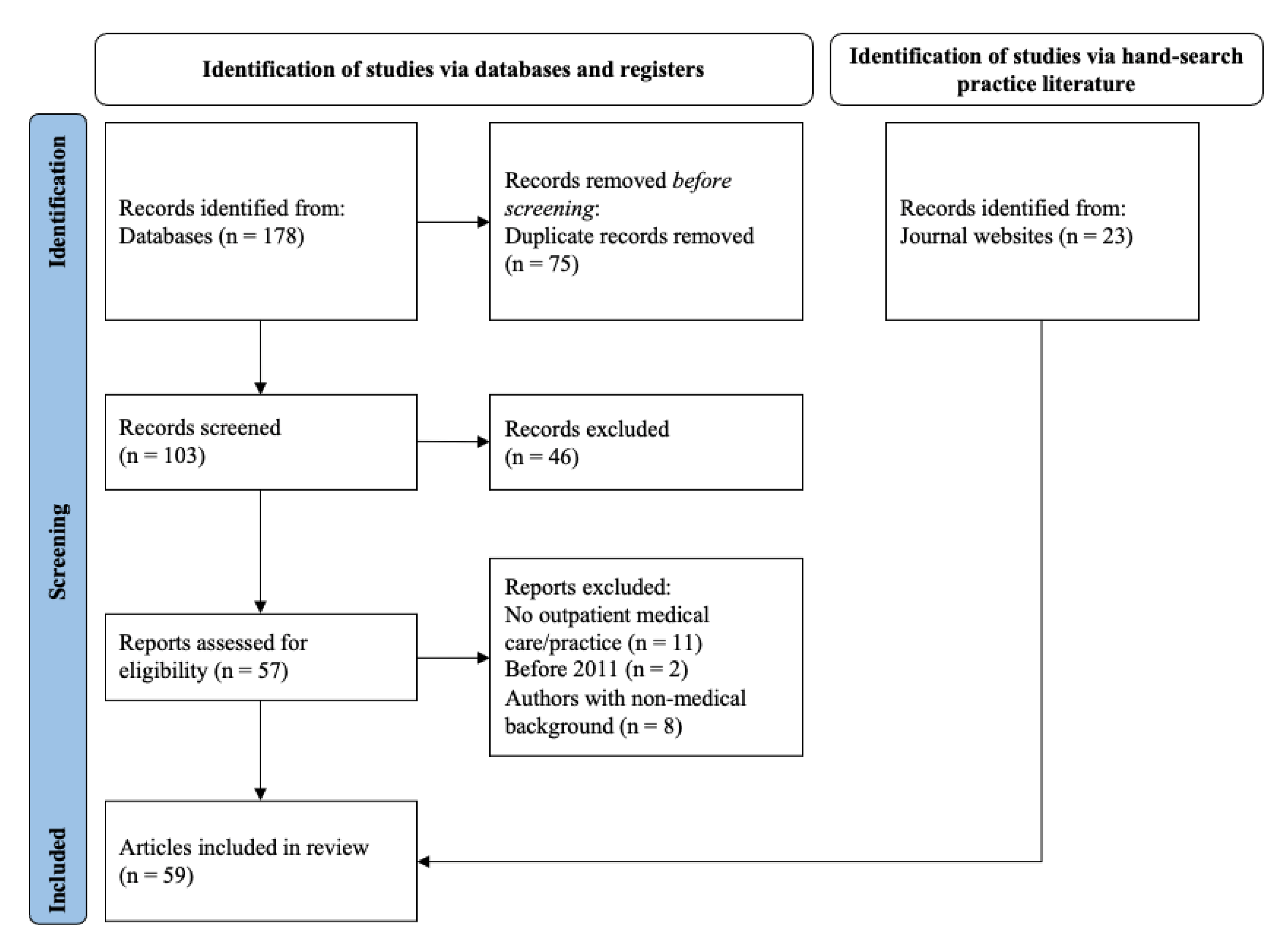

2.1. Scoping Review

2.1.1. Identification of Relevant Literature for Scoping Review

2.1.2. Screening and Selection of Relevant Literature

2.1.3. Data Extraction

2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.2.1. Participant Selection

2.2.2. Data Collection

2.2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Overview of Literature Results

3.2. Identified Perceptions and Arguments

3.2.1. Impact on Physician Autonomy

I would no longer be free to make my own decision afterwards, because in principle there could be pressure at some point to say that money has to be earned now, so that you might be restricted in your therapy and treatment options. (Interviewee 3, 56 years.)

3.2.2. Impact on Quality of Care

But I leave the decision up to him (patient), now that I have the freedom. But if I had economic guidelines or economic pressure on my neck, then I would probably tend more towards turnover and sell that to him. (Interviewee 10, 50 years.)

3.2.3. Impact on Work-Life Balance

I realized that I would rather work in a large team and with many colleagues. […] It’s the responsibility. You don’t just have your own existence that you carry, but many other existences in self-employment. […] And that doesn’t end on Friday afternoon at 3 pm. That’s when it probably starts with all the accounting, stuff and taxes, I don’t know what would probably be omitted, which you don’t learn in your studies. (Interviewee 8, 25 years.)

I don’t want to take out a loan of 800,000 or a million euros to buy a practice that I’ll have to pay off for the next 50 years because I don’t want to work that long. (Interviewee 14, 35 years.)

3.2.4. Impact on Sustainability

Actually, I think you guys [PE] are crap, but if you pay me that much money then you can have it.’ (Interviewee 10, 50 years.)

3.2.5. Lack of Medical vs. Managerial Expertise

So, considering this entrepreneurial activity and founding a practice, you might have two lectures, but you don’t really know anything about it.’ (Interviewee 9, 25 years.)

3.2.6. Taxation Issues

I actually find that rather reprehensible, because a large part of the money is more or less provided by our social system and that is a bit like plundering the state.’ (Interviewee 2, 53 years.)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scheffler, R.M.; Alexander, L.M.; Godwin, J.R. Soaring Private Equity Investment in the Healthcare Sector: Consolidation Accelerated, Competition Undermined, and Patients at Risk. 2021. Available online: https://publichealth.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Private-Equity-I-Healthcare-Report-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Appelbaum, E.; Batt, R. Private Equity Buyouts in Healthcare: Who Wins, Who Loses? Institute for New Economic Thinking Working: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalino, L.P.; Saiani, R.; Bhidya, S.; Khullar, D.; O’Donnell, E. Private equity acquisition of physician practices. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, 114–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWane, M.E.; Mostow, E.; Grant-Kels, J.M. The corporatization of care in academic dermatology. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 38, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilreath, M.; Morris, S.; Brill, J.V. Physician Practice Management and Private Equity: Market Forces Drive Change. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 1924–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, E.M.; Lelli, G.J.; Bhidya, S.; Casalino, L.P. The Growth of Private Equity Investment in Health Care: Perspectives from Ophthalmology. Health Affairs 2020, 39, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobsin, R. Finanzinvestoren in der Gesundheitsversorgung in Deutschland: 20 Jahre Private Equity—Eine Bestandsaufnahme, 4th ed.; Offizin-Verlag: Hannover, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Haaß, F.A.; Ochmann, R.; Julia, G.; Albrecht, M.; Nolting, H.-D. Investorenbetriebene MVZ in der Vertragszahnärztlichen Versorgung: Entwicklung und Auswirkungen; Duncker Humblot GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J.; Fisch, C.; Vismara, S.; Andres, R. Private equity investment criteria: An experimental conjoint analysis of venture capital, business angels, and family offices. J. Corp. Financ. 2019, 58, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompers, P.; Kaplan, S.N.; Mukharlyamov, V. What do private equity firms say they do? J. Financ. Econ. 2016, 121, 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondi, S.; Song, Z. Potential Implications of Private Equity Investments in Health Care Delivery. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 321, 1047–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.N.; Strömberg, P. Leveraged buyouts and private equity. J. Econ. Perspect. 2009, 23, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, S.; Francis, J. The evolution of private equity in dermatology. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 38, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, S.; Francis, J.; Motaparthi, K.; Grant-Kels, J.M. Future considerations for clinical dermatology in the setting of 21st century American policy reform: Corporatization and the rise of private equity in dermatology. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterloh, F. Patientenversorgung unter Druck: Gegen die Kommerzialisierung. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2019, 116. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/207864/Patientenversorgung-unter-Druck-Gegen-die-Kommerzialisierung (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Zhu, J.M.; Polsky, D. Private Equity and Physician Medical Practices—Navigating a Changing Ecosystem. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 981–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machi, L.A.; McEvoy, B.T. The Literature Review: Six Steps to Success, 2nd ed.; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- LA-MED. API-Studie 2021: Eine Untersuchung der LA-MED zur Nutzung Ärztlicher Fachmedien. Fahrdorf. 2021. Available online: https://la-med.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/LA-MED_API-2021_Broschüre.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkens, H. Selection Procedures, Sampling, Case Construction. In A Companion to Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Flick, U., von Kardorff, E., Steinke, I., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann, S.; Kvale, S. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kowal, S.; O’Connell, D.C. The Transcription of Conversations. In A companion to Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Flick, U., von Kardorff, E., Steinke, I., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C. The Analysis of Semi-structured Interviews. In A Companion to Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Flick, U., von Kardorff, E., Steinke, I., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Breannan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennenbach, R. Ist Private Equity für die ambulante Versorgung notwendig, ein Fortschritt oder eine Gefahr? MKG Chir. 2020, 13, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resneck, J.S.; Philip, R.L. Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.; Kohli, N. YPS Report: The Role of Private Equity in Medicine. Mo. Med. 2018, 115, 333. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30228757 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Patel, N.S.; Groth, S.; Sternberg, P. The Emergence of Private Equity in Ophthalmology. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 137, 601–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.E.; Rathi, V.K.; Naunheim, M.R. Implications of Private Equity Acquisition of Otolaryngology Physician Practices. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 146, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khetpal, S.; Lopez, J.; Steinbacher, D.M. Trends in Private Equity Deals in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Dentistry. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- aerztblatt.de. Wir kennen keinen Fall, in dem Kapitalinteressen die ärztliche Entscheidung infrage gestellt hätten. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2018. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=1&nid=98076&s=Private&s=equity (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- aerztblatt.de. Zahnärzte warnen vor MVZ-Übernahmen durch Kapitalinvestoren. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt. 2018. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=1&nid=99030&s=Private&s=equity (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Springer Medizin. Die Gesichter der dentalen Ketten. Junge Zahnarzt 2019, 10, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novice, T.; Portney, D.; Eshaq, M. Dermatology resident perspectives on practice ownership structures and private equity-backed group practices. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 38, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.A.; Afshar, S. Implications of Private Equity in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 1456–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satiani, B.; Zigrang, T.A.; Bailey-Wheaton, J.L. Should surgeons consider partnering with private equity investors? Am. J. Surg. 2020, 222, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, M.J.; Weiser, L.G.; Bosco, J.A. The Corporate Practice of Medicine. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2020, 102, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Seiger, K.; Renehan, P.; Mostaghimi, A. Trends in Private Equity Acquisition of Dermatology Practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- aerzteblatt.de. Gesundheitsexperten Stehen Fremdinvestoren Überwiegend Kritisch Gegenüber. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2020. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=&typ=1&nid=110813&s=Gesundheitsexperten&s=fremdinvestoren&s=kritisch (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Allroggen, S. Veränderung der Zahnmedizinischen Versorgungsstruktur aus Sicht einer Kassenzahnärztlichen Vereinigung. MKG Chir. 2020, 13, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzt-wirtschaft.de. Bundeszahnärztekammer fordert Stopp von Fremdkapital in der Zahnmedizin. A&W Online. 2020. Available online: https://www.arzt-wirtschaft.de/finanzen/honorare/bundeszahnaerztekammer-fordert-stopp-von-fremdkapital-in-der-zahnmedizin/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Francis, J.; Konda, S.; Motaparthi, K.; Grant-Kels, J.M. Response to letter to the editor from Bennett and further thoughts on the corporatization of dermatology and private equity–backed dermatology groups. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, e13–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, R.G. Further thoughts on dermatology and equity-owned dermatology practices. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, e11–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilreath, M.; Patel, N.C.; Suh, J.; Brill, J.V. Gastroenterology Physician Practice Management and Private Equity: Thriving in Uncertain Times. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1084–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, U.F. Investoren in der ambulanten Versorgung: Erst der Patient, dann die Ökonomie. Dtsch Ärzteblatt 2018, 115, A1692. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=16&aid=201048&s=Private&s=equity (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Zhu, J.M.; Hua, L.M.; Polsky, D. Private Equity Acquisitions of Physician Medical Groups Across Specialties, 2013–2016. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 323, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaljic, M.; Lipoff, J.B. Association of private equity ownership with increased employment of advanced practice professionals in outpatient dermatology offices. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 84, 1178–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, R.; Kelsey, A.; Grant-Kels, J.M. Comment on: Conflicts of interest for physician owners of private equity–owned medical practices. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, D.W. A Day at the Office: Private Practice and Private Equity. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2019, 477, 955–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- aerzteblatt.de. Union hat keine Bedenken bei Beteiligungen Renditeorientierter Kapitalanleger an MVZ. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2019. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=1&nid=107370&s=Kapitalanleger&s=MVZ&s=Union (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Resnick, M.J. Re: The growth of private equity investment in health care: Perspectives from ophthalmology. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laschet, H. Finanzierung: Private Equity in MVZ? Mehr Evidenz täte der Debatte gut. Ärzte Zeitung 2021. Available online: https://www.aerztezeitung.de/Wirtschaft/Private-Equity-in-MVZ-Mehr-Evidenz-taete-der-Debatte-gut-419020.html (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- aerzteblatt.de. Hartmannbund ruft zum Dialog über demografischen Wandel bei Ärzten auf. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2019. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=1&nid=107278&s=hartmannbund&s=ruft (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Wasner, A. Zahl der MVZ in Private-Equity-Besitz auch 2020 gestiegen. Med. Trib. 2021. Available online: https://www.medical-tribune.de/praxis-und-wirtschaft/niederlassung-und-kooperation/artikel/zahl-der-mvz-in-private-equity-besitz-auch-2020-gestiegen/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Kirsh, G.M.; Kapoor, D.A. Private Equity and Urology: An Emerging Model for Independent Practice. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 48, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korzilius, H. Ambulante Versorgung: Investoren auf Einkaufstour. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2018, 115, A1688–A1692. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/201014/Ambulante-Versorgung-Investoren-auf-Einkaufstour (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Maibach-Nagel, E. Fremdinvestoren im Gesundheitssystem: Ungesunder Wettbewerb. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2018, 115, A-1675. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/201003/Fremdinvestoren-im-Gesundheitssystem-Ungesunder-Wettbewerb (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Bruch, J.D.; Borsa, A.; Song, Z.; Richardson, S.S. Expansion of Private Equity Involvement in Women’s Health Care. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1542–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschet, H. Versorgung: Private Equity ist auch eine Chance. Ärzte Ztg. 2021. Available online: https://www.aerztezeitung.de/Politik/Private-Equity-ist-auch-eine-Chance-417854.html (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- arzt-wirtschaft.de. Pflegeheime und Praxen: Finanzinvestoren Greifen nach der Gesundheitsbranche. A&W Online. 2019. Available online: https://www.arzt-wirtschaft.de/finanzen/geldanlagen/pflegeheime-und-praxen-finanzinvestoren-greifen-nach-der-gesundheitsbranche/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Scheuplein, C.; Evans, L.M.; Merkel, S. Übernahmen durch Private Equity in Deutschen Gesundheitssektor: Eine Zwischenbilanz für die Jahre 2013 bis 2018; IAT Discussion Paper No. 19/01; IAT: Gelsenkirchen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P. Profit auf Kosten der Patientinnen und Patienten? MKG Chir. 2020, 13, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glöser, S. Gesundheitswesen wird für Investoren immer attraktiver. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2019, 116, 4. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=16&aid=206759&s=Gesundheitswesen&s=Investoren&s=attraktiver&s=f%FCr&s=immer&s=wird (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Hilienhof, A. Gesundheitsmarkt: Finanzinvestoren auf dem Vormarsch. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2019, 116, A340. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=16&aid=205710&s=Investoren&s=Vormarsch&s=auf&s=dem (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Laschet, H. Investoren im Gesundheitswesen: Plage oder Partner fürs Gemeinwohl? Ärzte Ztg. 2020. Available online: https://www.aerztezeitung.de/Politik/Investoren-im-Gesundheitswesen-Plage-oder-Partner-fuers-Gemeinwohl-413318.html (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- aerzteblatt.de. Gesundheitssektor zieht Investoren an. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 2019. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/treffer?mode=s&wo=1041&typ=1&nid=102620&s=Private&s=equity (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- DeCamp, M.; Sulmasy, L.S. Ethical and Professionalism Implications of Physician Employment and Health Care Business Practices: A Policy Paper From the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.M.; Marjoribanks, T. The impact of financial constraints and incentives on professional autonomy. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2003, 18, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasner, A. Wie stark werden sich Private-Equity- Übernahmen auf die ambulante Versorgung auswirken? Med. Trib. 2019. Available online: https://www.medical-tribune.de/praxis-und-wirtschaft/niederlassung-und-kooperation/artikel/wie-stark-werden-sich-private-equity-uebernahmen-auf-die-ambulante-versorgung-auswirken/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Gondi, S.; Song, Z. Private Equity Investment in Health Care. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 322, 468–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R. Private Equity Investments in Women’s Health and Obstetrics and Gynecology Practices. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 136, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.G. Conflicts of interest for physician owners of private equity—Owned medical practices. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.; Weech-Maldonado, R.; Harman, J.S.; Al-Amin, M.; Hyer, K. Private equity ownership of nursing homes: Implications for quality. J. Health Care Financ. 2014, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Howell, S.T.; Yannelis, C.; Gupta, A. Does Private Equity Investment in Healthcare Benefit Patients? Evidence from Nursing Homes. In National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series; No. 28474; The National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nolte, T.N.; Miedaner, F.; Sülz, S. Physicians’ Perspectives Regarding Private Equity Transactions in Outpatient Health Care—A Scoping Review and Qualitative Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315480

Nolte TN, Miedaner F, Sülz S. Physicians’ Perspectives Regarding Private Equity Transactions in Outpatient Health Care—A Scoping Review and Qualitative Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315480

Chicago/Turabian StyleNolte, Tim N., Felix Miedaner, and Sandra Sülz. 2022. "Physicians’ Perspectives Regarding Private Equity Transactions in Outpatient Health Care—A Scoping Review and Qualitative Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315480

APA StyleNolte, T. N., Miedaner, F., & Sülz, S. (2022). Physicians’ Perspectives Regarding Private Equity Transactions in Outpatient Health Care—A Scoping Review and Qualitative Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315480