Problem Behaviors of Adolescents: The Role of Family Socioeconomic Status, Parental Educational Expectations, and Adolescents’ Confidence in the Future

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Comprehensive Theoretical Model of Problem Behaviors

1.2. Association between Socioeconomic Status and Problem Behaviors

1.3. The Mediating Role of Parental Educational Expectations and Adolescents’ Confidence in the Future

1.4. The Current Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Family Socioeconomic Status

2.2.2. Problem Behaviors

2.2.3. Parental Educational Expectations

2.2.4. Confidence in the Future

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

2.3.2. Regression Models Analysis

2.3.3. Mediating Effect Analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. The Influence Mechanism of Family Socioeconomic Status on Problem Behaviors

3.2. Implications for Adolescents’ Problem Behaviors Prevention and Intervention

3.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, C.D.; Yang, Z.L.; Huang, X.T. The Comprehensive Dictionary of Psychology; Shanghai Educational Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2004; p. 1317. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lassi, Z.S.; Mahmud, S.; Syed, E.U.; Janjua, N.Z. Behavioural problems among children living in orphanage facilities of Karachi, Pakistan: Comparison of children in an SOS village with those in conventional orphanages. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GKjeldsen, A.; Nilson, W.; Gustavson, K.; Skipstein, A.; Melkevik, O.; Karevold, E. Predicting well-being and internalizing symptoms in late adolescence from trajectories of externalizing behavior starting in infancy. J. Res. Adolesc. 2016, 26, 991–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, H.E.; Shaw, D.S.; Burwell, R.A.; Nagin, D.S. Transactional processes in child disruptive behaviour and maternal depression: A longitudinal study from early childhood to adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2009, 21, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Border, R.; Corley, R.P.; Brown, S.A.; Hewitt, J.K.; Hopfer, C.J.; Stallings, M.C. Predictors of adult outcomes inclinically–and legally ascertained youth with externalizing problems. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, R.F.; Gau, J.M.; Seeley, J.R.; Kosty, D.B.; Sher, K.J.; Lewinsohn, P.M. Internalizing and externalizing disorders as predictors of alcohol use disorder onset during three developmental periods. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016, 164, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narusyte, J.; Ropponen, A.; Alexanderson, K.; Svedberg, P. Internalizing and externalizing problems in childhood and adolescence as predictors of work incapacity in young adulthood. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willoughby, T.; Chalmers, H.; Busseri, M. Where’s the syndrome? examining co-occurrence among multiple “problem” behaviours in youth. J. Clin. Consult. Psychol. 2004, 72, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1987, 57, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessor, R. Problem-behaviors theory, psychosocial development, and adolescent problem drinking. Br. J. Addict. 1987, 82, 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor, R.; Turbin, M.; Costa, F.M. Adolescent problem behaviors in China and the United States: A cross-national study of psychosocial protective factors. J. Res. Adolesc. 2003, 13, 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, K.A.; Gallo, L.C. Psychological perspectives on pathways linking socioeconomic status and physical health. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 501–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, R.H.; Corwyn, R.F. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Grath, P.J.; Elgar, F.J. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behaviorsal Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Pub Corp: St Frisco, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, G.; Hu, T.; Rost, D.H. Parental emotional warmth and psychological suzhi as mediators between socioeconomic status and problem behaviours in Chinese children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 59, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, L.G.; Wickrama, K.A.S.; Lee, T.K. Testing family stress and family investment explanations for conduct problems among African American adolescents. J. Marriage Fam. 2016, 78, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, P. A Study on the impact of parent-child relationship and socioeconomic status on sroblem Behaviour among Children. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Zhang, D.J. Socioeconomic status and young children’s problem behaviours—Mediating effffects of parenting style and psychological suzhi. Early Child Dev. Care 2021, 191, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, E.J.; Compton, S.N.; Keeler, G.; Angold, A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: A natural experiment. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2003, 290, 2023–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.Z.; Zhang, D.J.; Zhu, Z.G.; Li, J.J.; Chen, X. The effect of family socioeconomic status on adolescents’ problem behaviors: The chain mediating role of parental emotional warmth and belief in a just world. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2020, 36, 240–248. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, A.D.; Mistry, R.S. Congruence of mother and teacher educational expectations andlow-income youth’s academic competence. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, A.D.; Fernandez, C.C.; Hou, Y.; Gonzalez, C.S. Parent and teacher educational expectations and adolescents’ academic performance: Mechanisms of influence. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 2679–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D. Social psychological process mechanism of educational diversion in junior high school. Educ. Res. 2020, 3, 72–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenks, K.; Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. I can do this! The development and calibration of children’s expectations for success and competence beliefs. Dev. Rev. 2018, 48, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, C.M.; Lewis, M.; Rhonda, K.; Nilsen, C. The role of parent expectations on adolescent educational aspirations. Educ. Stud.-UK 2011, 37, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Q.; Shi, Y.W. Family background educational expectation and college dgree attainment an empirical study based on shanghai survey. Society 2014, 34, 175–195. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Yim, H.W.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, H.K.; Potenza, M.N.; Jo, S.J.; Son, H.J. A partial mediation effect of father-child attachment and self-esteem between parental marital conflict and subsequent features of internet gaming disorder in children: A 12-month follow-up study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guo, C. A meta-analysis of the relationship between self-esteem and aggression among Chinese students. Aggress Violent Beh. 2015, 21, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.G.; Yang, C.Y.; Liu, G.Z.; Chan, M.K.; Liu, C.X.; Zhang, D.J. Peer victimization and problem behaviors: The roles of self-esteem and parental attachment among Chinese adolescents. Child Dev. 2020, 91, e968–e983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, M.; Hooda, D. Perceived parenting style as a predictor of hope among adolescents. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 38, 174–178. Available online: http://www.jiaap.org.in/Listing_Detail/Logo/78a1c950-57b1-41b8-9df3-a466e69ad18d.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Wen, M.; Lin, D. Child development in rural China: Children left behind by their migrant parents and children of nonmigrant families. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.P.; Huang, X.T. A Research on college students’ self-confidence: The theoretical construct. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 29, 563–569. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.M.; Winnard, E.J. Looking ahead through lenses of justice: The relevance of just-world beliefs to intentions and confidence in the future. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 46, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Huang, X. Critical review of psychological studies on hope. Adv. Meth. Pract. Psychol. 2013, 21, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.N.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.W.; Guirong Song, G.R.; Liu, Q.G.; Tang, X. The relationship between parent-adolescent communication and depressive symptoms: The roles of school life experience, learning difficulties and confidence in the future. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 1295–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.L. The impact of family socioeconomic status on students’ academic performance from the perspective of individuals and schools: Implications from the program for international student assessment (PISA). Shanghai Educ. Res. 2009, 12, 4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.Y. Analysis of ten social strata in contemporary China. J. Learn. Pract. 2002, 3, 55–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.G.; Shen, J.L. The relationships among family SES, intelligence, intrinsic motivation and creativity. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2007, 23, 30–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.S.; Chen, Y.M.; Hou, X.; Gao, F.Q. Social economic status and study engagement: The mediating effects of academic self-efficacy among junior high school students. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2013, 29, 71–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Xie, G.H. The impact of school class on junior high school students’ educational expectation. Society 2017, 37, 6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R.D.; Conger, K.G.; Martin, M.J. Socioeconomic Status, Family Processes, and Individual Development. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T.; Sheikh-Khalil, S. Does parental involvement matter for student achievement and mental health in high school? Child Dev. 2014, 85, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Shin, J.; Choi, D.W.; Kim, K.; Park, E.C. Effects of household income change on children’s problem behaviors: Findings from a longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of mediating effects: The development of methods and models. Adv. Meth. Pract. Psychol. 2014, 22, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory. In Annals of Child Development; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 1989; pp. 187–249. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1992-98662-005 (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Costa, F.M.; Jessor, R.; Turbin, M.S. Transition into adolescent problem drinking: The role of psychosocial risk and protective factors. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 1999, 60, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galin, S.; Heruti, I.; Barak, N.; Gotkine, M. Hope and self-efficacy are associated with better satisfaction with life in people with ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2018, 19, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.C.; Yu, T.N.; Chang, O.D.; Hirsch, J.K. Hope and trauma: Examining a diathesis-stress model in predicting depressive and anxious symptoms in college students. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 96, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trezise, A.; McLaren, S.; Gomez, R.; Bice, B.; Hodgetts, J. Resiliency among older adults: Dispositional hope as a protective factor in the insomnia–depressive symptoms relation. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 22, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, A.B.I.; Khan, A.; Salanga, M.G.C. Hope and satisfaction with life: Testing the mediating roles of self-ssteem in three Asian cultures. Acción Psicol. 2018, 15, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Family socioeconomic status | 0.28 | 3.69 | |||||

| 2 Parental educational expectation | 6.53 | 1.92 | 0.193 *** | ||||

| 3 Adolescents’ confidence in the future | 3.15 | 0.70 | 0.166 *** | 0.160 *** | |||

| 4 Adolescents’ problem behaviors | 15.34 | 4.68 | −0.129 *** | −0.180 *** | −0.201 *** | ||

| 5 Parental relationships | 0.91 | 0.29 | 0.025 * | 0.053 *** | 0.108 *** | −0.113 *** | |

| 6 Gender | −0.012 | −0.081 *** | 0.019 | 0.148 *** | 0.030 * |

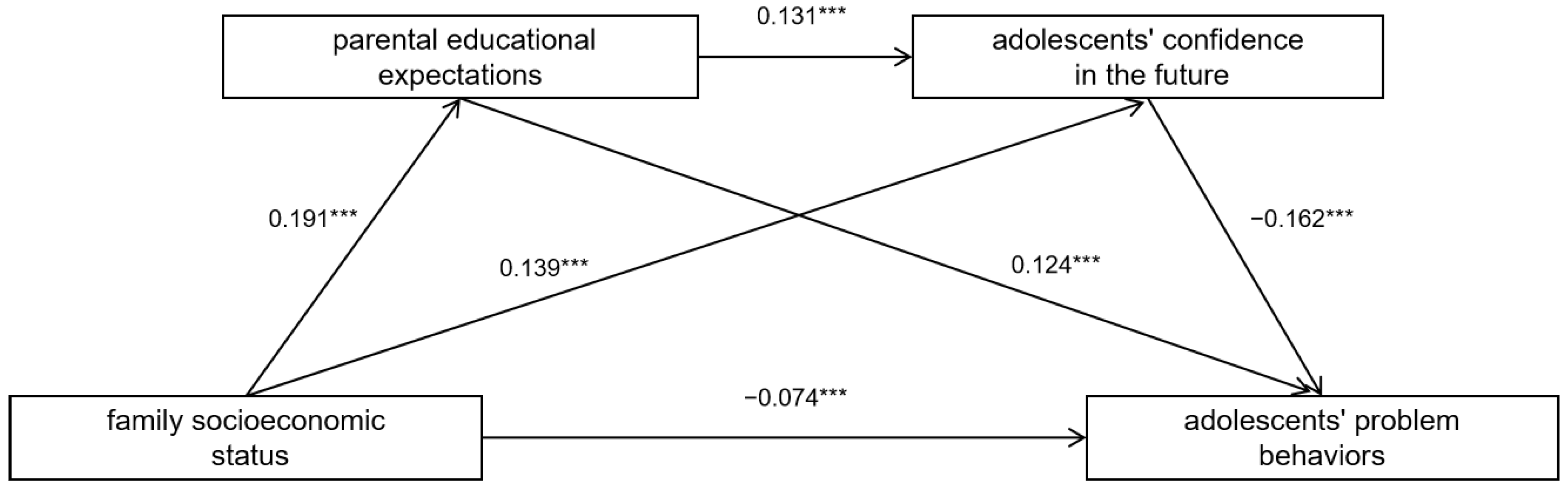

| Variables | Equation 1 | Equation 2 | Equation 3 | Equation 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | b | t | b | t | |

| Family socioeconomic status | −0.125 *** | −10.604 | 0.191 *** | 16.224 | 0.139 *** | 11.647 | −0.074 *** | −6.304 |

| Parental educational expectations | 0.131 *** | 10.881 | −0.124 *** | −10.437 | ||||

| Adolescents’ confidence in the future | −0.162 *** | −13.737 | ||||||

| Gender | 0.150 *** | 12.772 | −0.081 *** | −6.840 | 0.028 * | 2.394 | 0.143 *** | 12.416 |

| Parental relationships | 0.050 *** | 4.255 | 0.096 *** | 8.200 | −0.092 *** | −7.944 | ||

| R | 0.226 | 0.215 | 0.234 | 0.310 | ||||

| R2 | 0.051 | 0.046 | 0.055 | 0.096 | ||||

| F | 123.978 *** | 110.924 *** | 100.062 *** | 146.169 *** | ||||

| Indirect Effect Size | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total indirect effect | −0.050 | 0.004 | −0.058 | −0.042 | 100% |

| Indirect effect 1 | −0.024 | 0.003 | −0.030 | −0.017 | 47.11% |

| Indirect effect 2 | −0.023 | 0.003 | −0.028 | −0.017 | 44.91% |

| Indirect effect 3 | −0.004 | 0.001 | −0.005 | −0.003 | 7.98% |

| Comparison 1 | −0.001 | 0.005 | −0.010 | 0.008 | |

| Comparison 2 | −0.020 | 0.003 | −0.026 | −0.013 | |

| Comparison 3 | −0.019 | 0.003 | −0.024 | −0.014 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ouyang, Y.; Ding, D.; Xu, X. Problem Behaviors of Adolescents: The Role of Family Socioeconomic Status, Parental Educational Expectations, and Adolescents’ Confidence in the Future. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315442

Ouyang Y, Ding D, Xu X. Problem Behaviors of Adolescents: The Role of Family Socioeconomic Status, Parental Educational Expectations, and Adolescents’ Confidence in the Future. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315442

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuyang, Yanwen, Daoqun Ding, and Xizheng Xu. 2022. "Problem Behaviors of Adolescents: The Role of Family Socioeconomic Status, Parental Educational Expectations, and Adolescents’ Confidence in the Future" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315442

APA StyleOuyang, Y., Ding, D., & Xu, X. (2022). Problem Behaviors of Adolescents: The Role of Family Socioeconomic Status, Parental Educational Expectations, and Adolescents’ Confidence in the Future. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315442