Forensic Characteristics of Physical Elder Abuse and Current Status and Issues of Collaboration between Forensic Medicine Departments and Related Institutions in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Target Facilities

2.2. Data Collection and Survey Period

2.3. Statistical Analysis

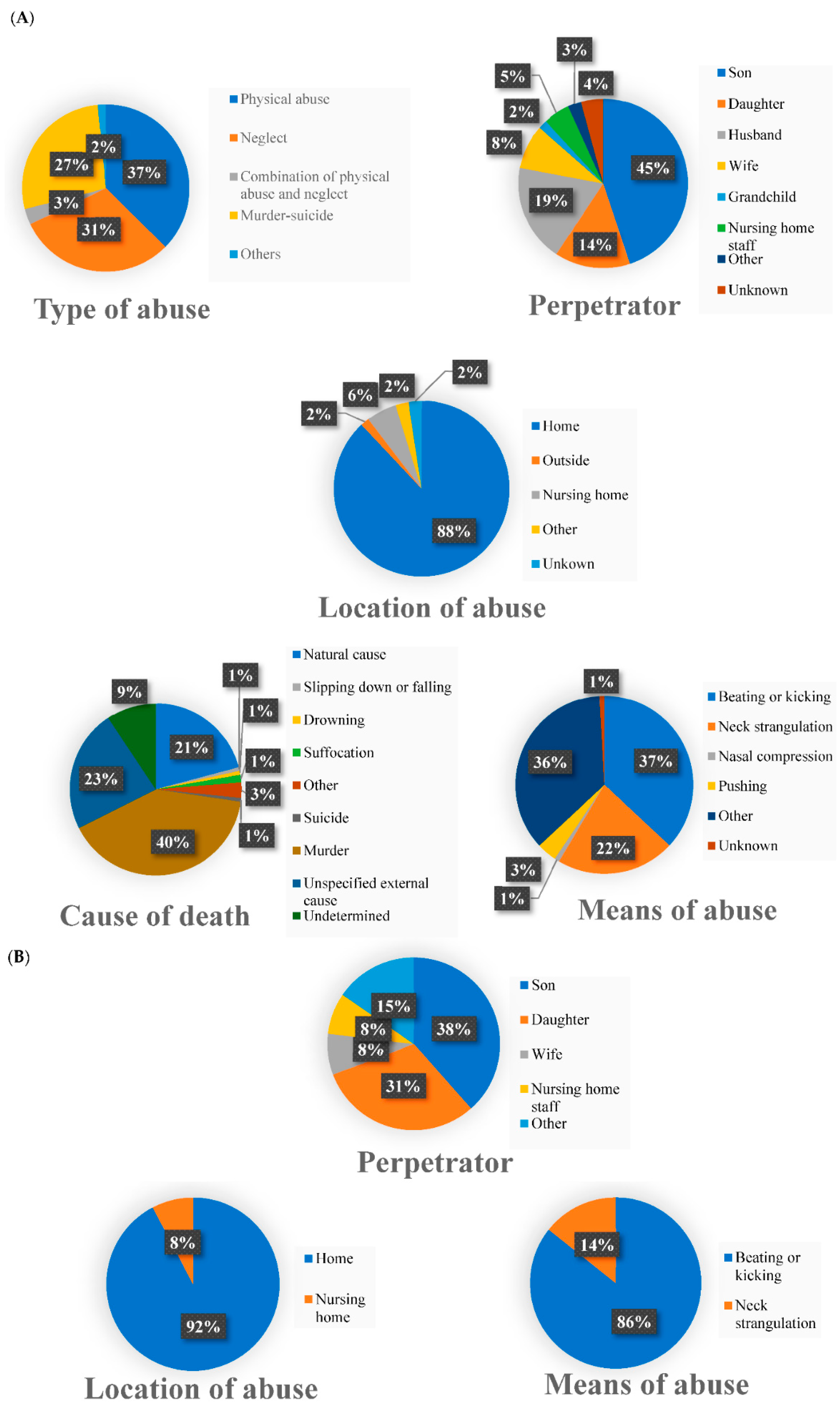

3. Results

3.1. Responses from Forensic Medicine Departments

3.1.1. Autopsy Cases

3.1.2. Cases of Elder Abuse Other Than Autopsy Cases

3.1.3. Injuries in Victims of Elder Abuse

3.1.4. Collaboration with Hospitals

3.1.5. Collaboration with Municipalities or Public Community General Support Centers

3.1.6. Trends in Elder Abuse

3.2. Responses from Related Institutions

3.2.1. Responses from Hospitals

3.2.2. Responses from Municipalities

3.2.3. Responses from Public Community General Support Centers

4. Discussion

4.1. Forensic Characteristics of Physical Elder Abuse

4.2. Current Status and Issues of Collaboration between Forensic Medicine Departments and Related Institutions

4.3. Current Status and Issues of Cooperation between Hospitals, Municipalities and Public Community General Support Centers

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burston, G.R. Letter: Granny-battering. Br. Med. J. 1975, 3, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. European Report on Preventing Elder Maltreatment. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/144676/e95110.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Acierno, R.; Hernandez, M.A.; Amstadter, A.B.; Resnick, H.S.; Steve, K.; Muzzy, W.; Kilpatrick, D.G. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skirbekk, V.; James, K.S. Abuse against elderly in India--the role of education. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yon, Y.; Mikton, C.R.; Gassoumis, Z.D.; Wilber, K.H. Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017, 5, e147–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbow, S.M.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Kingston, P.; Peisah, C. Invisible and at-risk: Older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Elder. Abus. Negl. 2022, 34, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, P.; Chen, Y. Prevalence of elder abuse and victim-related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.S.; Levy, B.R. High Prevalence of Elder Abuse During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk and Resilience Factors. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaroun, L.K.; Bachrach, R.L.; Rosland, A.M. Elder Abuse in the Time of COVID-19-Increased Risks for Older Adults and Their Caregivers. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.D.; Mosqueda, L. Elder Abuse in the COVID-19 Era. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1386–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Abuse of Older People. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/elder-abuse (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Takizawa, K. Koureishagyakutaiboushihou no gaiyou [elder abuse and prevention of abuse: The overview of Act on the Prevention of Elder Abuse, Support for Caregivers of Elderly Persons and Other Related Matters]. Jpn. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 19, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer, K.; Burnes, D.; Riffin, C.; Lachs, M.S. Elder Abuse: Global Situation, Risk Factors, and Prevention Strategies. Gerontologist 2016, 56 (Suppl. S2), S194–S205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppata, M. Koronaka ni okeru koureishano jinkenyougo-kateinai to sisetsunai no jittai to kadai reiwagannendo koureishagyakutaiboushihou ni motoduku chousakekka no omona gaiyou ni tsuite [Protection of human rights of elder adults during the COVID-19 pandemic-The reality and challenges at home and in institutions for older adults. Summary of the findings based on the 2019 survey conducted under the Elder Abuse Protectiom Law]. J. Jpn. Acad. Prev. Elder Abus. 2021, 17, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Investigative Commission about Public Community General Support Centers Operation Manual. Chiikihoukatsu Shiennsenta Uneimanyuaru [Operation Manual of Public Community General Support Centers: To More Implementation of Comprehensive Regional Care and Realization of Community Coexistence], 2nd ed.; Foundation of Social Development for Senior Citizens: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; 310p. [Google Scholar]

- Sendai Center for Dementia Care Research and Practice. Koureishagyakutai ni Okeru Jyuutokujian -Tokuchou to Kensyou no Shishin-[Serious Cases of Elder ABUSE ~Characteristics and Guide of Verification~]. Available online: https://www.dcnet.gr.jp/pdf/download/support/research/center3/311/s_h29gyakutaijyutokushisin.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Akaza, K.; Bunai, Y.; Tsujinaka, M.; Nakamura, I.; Nagai, A.; Tsukata, Y.; Ohya, I. Elder abuse and neglect: Social problems revealed from 15 autopsy cases. Leg. Med. 2003, 5, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatuka, H. Jidougyakutaiheno houigakukarano apurochi [Clinical Forensic Medicine and Child Abuse]. Niigata Med. J. 2012, 126, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Council for Maternal and Child Health Promotion. Jidougyakutaitaiou ni Okeru Houigaku Tono Renkeikyouka ni Kansuru Kenkyuu [The Study about Strengthening Cooperation with Forensic Science in Response to Child Abuse]. Available online: http://bosui.or.jp/research01.html (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Sweileh, W.M. Global Research Activity on Elder Abuse: A Bibliometric Analysis (1950–2017). J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2021, 23, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Brito Abath, M.; Leal, M.C.C.; de Melo Filho, D.A.; Oliveira Marques, A.P. Physical abuse of older people reported at the Institute of Forensic Medicine in Recife, Pernambuco State, Brazil. Cad. Saude Publica 2010, 26, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachs, M.S.; Pillemer, K.A. Elder Abuse. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLiema, M.; Navarro, A.E.; Moss, M.; Wilber, K.H. Prosecutors’ Perspectives on Elder Justice Using an Elder Abuse Forensic Center. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2016, 41, 780–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnes, D.; Kirchin, D.; Elman, A.; Breckman, R.; Lachs, M.S.; Rosen, T. Developing standard data for elder abuse multidisciplinary teams: A critical objective. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2020, 32, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.A. Elder maltreatment: A review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2006, 130, 1290–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Waa, S.; Jaffer, H.; Sauter, A.; Chan, A. A literature review of findings in physical elder abuse. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2013, 64, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, T.; LoFaso, V.M.; Bloemen, E.M.; Clark, S.; McCarthy, T.J.; Reisig, C.; Gogia, K.; Elman, A.; Markarian, A.; Flomenbaum, N.E.; et al. Identifying Injury Patterns Associated With Physical Elder Abuse: Analysis of Legally Adjudicated Cases. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 76, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, F.; Caputo, F.; Molinelli, A. Medico-legal aspects of deaths related to neglect and abandonment in the elderly. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 1399–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranitharan, P.; Pollanen, M.S. The interaction of injury and disease in the elderly: A case report of fatal elder abuse. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2009, 16, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houten, M.E.; Vloet, L.C.M.; Pelgrim, T.; Reijnders, U.J.L.; Berben, S.A.A. Types, characteristics and anatomic location of physical signs in elder abuse: A systematic review: Awareness and recognition of injury patterns. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 13, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, A. The Forensic Nurse’s Evolving Role in Addressing Elder Maltreatment in the United States. J. Forensic Nurs. 2021, 17, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, N.; Tatara, T. Beikoku kariforuniasyu no koureishagyakutaihouigakusenta ni kansuru genchichousahoukoku [Report on a Field Survey of Elder Abuse Forensic Centers in California, USA]. J. Jpn. Acad. Prev. Elder Abus. 2010, 6, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc.; Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University; New York City Department for the Aging. Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study: Self-Reported Prevalence and Documented Case Surveys. Available online: https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/Under%20the%20Radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Oppata, M. Sosharuwakujissen ni Yoru Koureishagyakutaiyobou [The Prevention of Elder Abuse through Social Work Practice]; Minjiho Kenkyukai: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; pp. 8, 315. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Child Death Review (CDR) Kuninotorikumi [National Initiatives for Child Death Review(CDR)]. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000728945.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Japan Academy for the Prevention of Elder Abuse. Dear Members, Proposed Amendments to the Elder Abuse Prevention Act. Available online: https://japea.jp/4111 (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Arakawa, T.; Otani, K.; Takenaka, M.; Nishitani, M.; Ono, M.; Fujita, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Kishi, N. Iryou Sosharuwaaka No Shigoto Genba Karano Teigen [The Work of Medical Social Workers: Recommendations from the Field]; Kawashima Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2000; pp. ix, 177. [Google Scholar]

- American Bar Association. Hallmarks of EAFRT. Available online: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/law_aging/resources/elder_abuse/elder-abuse-fatality-review-team-projects-and-resources/hallmarks-of-eafrt/ (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Stiegel, L.A. Elder Abuse Fatality Review Teams: A Replication Manual | OVC. Available online: https://ovc.ojp.gov/library/publications/elder-abuse-fatality-review-teams-replication-manual (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Melchiorre, M.G.; Chiatti, C.; Lamura, G.; Torres-Gonzales, F.; Stankunas, M.; Lindert, J.; Ioannidi-Kapolou, E.; Barros, H.; Macassa, G.; Soares, J.F. Social support, socio-economic status, health and abuse among older people in seven European countries. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.E.Z.; Maxwell, C.D.; Tatro, R.; Fales, K.; Hogoboom, B. Development and Implementation of a Coordinated Community Response to Address Elder Abuse and Neglect. J. Forensic Nurs. 2022, 18, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Simon, M.A. Association between elder abuse and use of ED: Findings from the Chicago Health and Aging Project. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 31, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, T.; Stern, M.E.; Elman, A.; Mulcare, M.R. Identifying and Initiating Intervention for Elder Abuse and Neglect in the Emergency Department. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 34, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motamedi, A.; Ludvigsson, M.; Simmons, J. Factors associated with health care providers speaking with older patients about being subjected to abuse. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2022, 34, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, T.; Mehta-Naik, N.; Elman, A.; Mulcare, M.R.; Stern, M.E.; Clark, S.; Sharma, R.; LoFaso, V.M.; Breckman, R.; Lachs, M.; et al. Improving Quality of Care in Hospitals for Victims of Elder Mistreatment: Development of the Vulnerable Elder Protection Team. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2018, 44, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, T.; Stern, M.E.; Mulcare, M.R.; Elman, A.; McCarthy, T.J.; LoFaso, V.M.; Bloemen, E.M.; Clark, S.; Sharma, R.; Breckman, R.; et al. Emergency department provider perspectives on elder abuse and development of a novel ED-based multidisciplinary intervention team. Emerg. Med. J. 2018, 35, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblatt, D.E.; Cho, K.H.; Durance, P.W. Reporting mistreatment of older adults: The role of physicians. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1996, 44, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, A.C.; Rosen, T.; Navarro, A.; Homeier, D.; Chennapan, K.; Mosqueda, L. Developing the Geriatric Injury Documentation Tool (Geri-IDT) to Improve Documentation of Physical Findings in Injured Older Adults. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiglesworth, A.; Mosqueda, L.; Burnight, K.; Younglove, T.; Jeske, D. Findings from an elder abuse forensic center. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Navarro, A.E.; Wilber, K.H.; Yonashiro, J.; Homeier, D.C. Do we really need another meeting? Lessons from the Los Angeles County Elder Abuse Forensic Center. Gerontologist 2010, 50, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, C.B.; Halphen, J.M.; Lee, J.; Flores, R.J.; Booker, J.G.; Reilley, B.; Burnett, J. Stemming the Tide of Elder Mistreatment: A Medical School-State Agency Collaborative. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Gratteri, S.; Sacco, M.A.; Scalise, C.; Cacciatore, G.; Bonetta, F.; Zibetti, A.; Aloe, L.; Sicilia, F.; Cordasco, F.; et al. COVID-19 emergency in prison: Current management and forensic perspectives. Med. Leg. J. 2020, 88, 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.J.; Ross, L. Adult Protective Services Training: A Brief Report on the State of the Nation. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2021, 33, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Site/Type | n | % | Site/Type | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head/incised wound | 3 | 21.4 | Chest or abdomen/fracture | 7 | 50.0 |

| Head/stab wound | 2 | 14.3 | Back/incised wound | 2 | 14.3 |

| Head/impression | 1 | 7.1 | Back/stab wound | 2 | 14.3 |

| Head/abrasion | 7 | 50.0 | Back/abrasion | 6 | 42.9 |

| Head/subcutaneous haemorrhage | 12 | 85.7 | Back/subcutaneous hemorrhage | 9 | 64.3 |

| Head/contusion | 4 | 28.6 | Back/burn | 3 | 21.4 |

| Head/laceration | 3 | 21.4 | Back/fracture | 1 | 7.1 |

| Head/burn | 3 | 21.4 | Upper extremity/incised wound | 3 | 21.4 |

| Head/fracture | 1 | 7.1 | Upper extremity/stab wound | 3 | 21.4 |

| Neck/incised wound | 4 | 28.6 | Upper extremity/abrasion | 4 | 28.6 |

| Neck/stab wound | 4 | 28.6 | Upper extremity/subcutaneous hemorrhage | 11 | 78.6 |

| Neck/impression | 7 | 50.0 | Upper extremity/contusion | 1 | 7.1 |

| Neck/abrasion | 4 | 28.6 | Upper extremity/laceration | 1 | 7.1 |

| Neck/subcutaneous hemorrhage | 9 | 64.3 | Upper extremity/burn | 3 | 21.4 |

| Neck/contusion | 1 | 7.1 | Lower extremity/incised wound | 2 | 14.3 |

| Neck/laceration | 1 | 7.1 | Lower extremity/stab wound | 2 | 14.3 |

| Neck/burn | 3 | 21.4 | Lower extremity/abrasion | 5 | 35.7 |

| Neck/fracture | 2 | 14.3 | Lower extremity/subcutaneous hemorrhage | 9 | 64.3 |

| Chest or abdomen/incised wound | 4 | 28.6 | Lower extremity/contusion | 2 | 14.3 |

| Chest or abdomen/stab wound | 5 | 35.7 | Lower extremity/laceration | 1 | 7.1 |

| Chest or abdomen/abrasion | 4 | 28.6 | Lower extremity/burn | 3 | 21.4 |

| Chest or abdomen/subcutaneous hemorrhage | 10 | 71.4 | External genital/burn | 2 | 14.3 |

| Chest or abdomen/contusion | 1 | 7.1 | Anus/burn | 2 | 14.3 |

| Chest or abdomen/laceration | 1 | 7.1 | |||

| Chest or abdomen/burn | 3 | 21.4 | |||

| Site | n | % | Type | n | % |

| Head | 13 | 92.9 | Subcutaneous hemorrhage | 12 | 85.7 |

| Neck | 12 | 85.7 | Abrasion | 10 | 71.4 |

| Back | 12 | 85.7 | Impression | 7 | 50.0 |

| Upper extremities | 12 | 85.7 | Fracture | 7 | 50.0 |

| Chest or abdomen | 11 | 78.6 | Stab wound | 5 | 35.7 |

| Lower extremities | 10 | 71.4 | Contusion | 5 | 35.7 |

| External genitalia | 2 | 14.3 | Incised wound | 4 | 28.6 |

| Anus | 2 | 14.3 | Laceration | 3 | 21.4 |

| Burn | 3 | 21.4 |

| Things enabled or possibly enabled by collaborating with hospitals | ||

| n | % | |

| Assessment from both clinical and forensic perspectives | 22 | 73.3 |

| Accurate judgement about mechanism of injury | 18 | 60.0 |

| Collaboration with clinical departments | 17 | 56.7 |

| Able to avoid overlooking injuries | 13 | 43.3 |

| Collaboration with the manager of the regional medical liaison office in the hospital | 7 | 23.3 |

| Other | 3 | 10.0 |

| Requirements for strengthening collaboration with hospitals | ||

| n | % | |

| Conducting training on the roles of forensic medicine in measures against elder abuse | 18 | 58.1 |

| Providing information about enquiries desks for handling elder abuse at hospitals and forensic medicine departments | 14 | 45.2 |

| Having regular opportunities to exchange opinions | 14 | 45.2 |

| Preparing a list of forensic medicine departments that can handle elder abuse | 10 | 32.3 |

| Preparing a manual for collaboration with forensic medicine departments in each hospital | 10 | 32.3 |

| Preparing a brochure about the roles of forensic medicine in measures against elder abuse | 8 | 25.8 |

| Other | 3 | 9.7 |

| Things needed for hospitals to easily contact forensic medicine departments | ||

| n | % | |

| Building relationships for easy consultation | 17 | 54.8 |

| Exchanging opinions between forensic practitioners and hospitals face to face | 16 | 51.6 |

| Clarifying the person in charge and the role of hospitals in elder abuse | 12 | 38.7 |

| Public awareness activities about assessments for elder abuse | 11 | 35.5 |

| Other | 6 | 19.4 |

| Things enabled or possibly enabled by collaborating with municipalities | ||

| n | % | |

| Precise judgement of whether abuse occurred | 11 | 55.0 |

| Able to provide an objective explanation to the abuser (including suspected abuse) | 10 | 50.0 |

| Precise judgement of whether temporary separation is needed | 10 | 50.0 |

| Useful for court documents | 9 | 45.0 |

| Improvement of the quality and knowledge of staff in municipalities | 9 | 45.0 |

| Other | 2 | 10.0 |

| Requirements for strengthening collaboration with municipalities | ||

| n | % | |

| Budget acquisition for direct and indirect assessment of living patients | 17 | 53.1 |

| Conducting training on the roles of forensic medicine in measures against elder abuse | 15 | 46.9 |

| Having regular opportunities to exchange opinions | 15 | 46.9 |

| Providing information about enquiries desks for handling elder abuse in municipalities and forensic medicine departments | 14 | 43.8 |

| Preparing a list of forensic medicine departments that can handle elder abuse | 13 | 40.6 |

| Preparing a brochure about the roles of forensic medicine in measures against elder abuse | 9 | 28.1 |

| Other | 4 | 12.5 |

| Things needed for municipalities to easily contact forensic medicine departments | ||

| n | % | |

| Exchanging opinions between forensic practitioners and municipalities face to face | 23 | 71.9 |

| Clarifying the person in charge and the role of municipalities in elder abuse | 15 | 46.9 |

| Building relationships for easy consultation | 13 | 40.6 |

| Public awareness activity about assessment of elder abuse | 12 | 37.5 |

| Other | 3 | 9.4 |

| Hospitals | Municipalities | Public Community General Support Centers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case of elder abuse in FY2019 | Yes (16%) No (84%) | Yes (81.5%) No (18.5%) | Yes (87%) No (13%) |

| Sex | Male 21 Female 49 | Male 398 Female 1155 | Male 209 Female 532 |

| Age | 80s (38%) 70s (35%) | 80s (42%) 70s (34%) | 80s (49%) 70s (32%) |

| Type of abuse | Physical abuse (40%) Neglect (33%) | Physical abuse (46%) Neglect (13%) | Physical abuse (49%) Neglect (13%) |

| Perpetrator | Son (39%) husband (24%) | Son (40%) Husband (23%) | Son (42%) Husband (20%) |

| Location of abuse | Home (95.5%) | Home (84%) | Home (97%) |

| Means of abuse | Beating or kicking (42%) Pushing (14%) | Beating or kicking (62%) Pushing (6%) | Beating or kicking (68%) Pushing (6%) |

| Reporter of abuse | Care manager (63.6%) Hospital staff (45.5%) | Care manager (72.3%) Police (55.9%) | Care manager (77.9%) Police (40.7%) |

| Background of elder abuse | Staff noticed findings of abuse (including suspected abuse) during medical examination (60.9%) | - | - |

| Cases reported to municipalities | Yes (60.9%) No (39.1%) | - | - |

| Received feedback from municipalities | Yes (53.8%) No (46.2%) | - | - |

| Route of consultation | Public community general support centers refer the patient (47.8%) Emergency transport (43.5%) | - | - |

| Clinical department consulted about abuse | Internal medicine (68.2%) Emergency (40.9%) | - | - |

| Case in which the victim was temporarily separated from the perpetrator | - | Yes (78.7%) No (21.3%) | Yes (66.2%) No (33.8%) |

| Case in which could not make a decision on temporary separation | - | Yes (28.4%) No (71.6%) | Yes (29.1%) No (70.9%) |

| Reason a decision could not be made on temporary separation | - | Difficulty judging whether the injury was abuse or an accident (35.4%) | Difficulty judging whether the injury was abuse or an accident (21.8%) |

| Follow-up work on cases | - | No (32.8%) | No (13.2%) |

| Case where it was difficult to judge whether abuse occurred | Yes (47.6%) No (52.4%) | Yes (49.2%) No (50.8%) | Yes (42.3%) No (57.7%) |

| Reason it was difficult to judge whether abuse occurred | Difficulty judging whether neglect occurred Difficulty distinguishing between abuse and repeated falls at home | Because the victim had dementia and an interview was not possible, so staff could not judge if caused by fall or violence | Because the victim with fall risk had dementia and did not remember, so it was difficult to judge if abuse or fall caused the bruising |

| Trends noticed in elder abuse | Elder abuse definitely increased (65%) | Elder abuse definitely increased (41.3%) | Elder abuse definitely increased (49.5%) |

| Photos taken of injury | Yes (68.2%) | Yes (64.5%) | Yes (60%) |

| Observation of injury | - | Visual observation (92.5%) Photos taken beforehand (54%) | Visual observation (92.1%) Photos taken beforehand (42.9%) |

| Hospitals | Municipalities | Public Community General Support Centers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of Collaboration | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Precise judgment of whether abuse occurred | 15 | 68.2 | 79 | 68.7 | 48 | 46.2 |

| Precise judgement of whether temporary separation is needed | 13 | 59.1 | 82 | 71.3 | 62 | 59.6 |

| Able to provide objective explanations to the abuser | 8 | 36.4 | 75 | 65.2 | 65 | 62.5 |

| Useful for court documents | 2 | 9.1 | 11 | 9.6 | 10 | 9.6 |

| Improvement of the quality and knowledge of staff | 5 | 22.7 | 33 | 28.7 | 23 | 22.1 |

| Leading to support for handing abuse | 18 | 81.8 | 69 | 60.0 | 59 | 56.7 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 7 | 6.1 | 12 | 11.5 |

| Improvements for strengthening collaboration | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Conducting training on collaboration | 65 | 48.5 | 118 | 52.7 | 120 | 52.9 |

| Creating manuals for collaboration | 69 | 51.5 | 100 | 44.6 | 97 | 42.7 |

| Providing information about enquiries desks | 74 | 55.2 | 93 | 41.5 | 90 | 39.6 |

| Having opportunities for regular exchange of opinions | 67 | 50.0 | 137 | 61.2 | 134 | 59.0 |

| Other | 4 | 3.0 | 6 | 2.7 | 10 | 4.4 |

| Reasons for lack of collaboration with forensic practitioners | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| There was no precedent | 90 | 64.7 | 114 | 48.7 | 140 | 57.1 |

| There was no forensic practitioner nearby | 49 | 35.3 | 165 | 70.5 | 165 | 67.3 |

| Not understanding how forensic medicine is involved in elder abuse cases | 59 | 42.4 | 159 | 67.9 | 179 | 73.1 |

| Not knowing about the enquiries desk for consultation | 51 | 36.7 | 127 | 54.3 | 157 | 64.1 |

| Able to handle cases of elder abuse with hospitals | 13 | 9.4 | 65 | 27.8 | 55 | 22.4 |

| No budget available | 4 | 2.9 | 63 | 26.9 | 33 | 13.5 |

| Other | 7 | 5.0 | 7 | 3.0 | 16 | 6.5 |

| Improvements for strengthening collaboration with forensic practitioners | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Conducting training on the roles of forensic medicine in measures against elder abuse | 60 | 47.2 | 127 | 62.0 | 154 | 73.0 |

| Creating brochures about the roles of forensic medicine in measures against elder abuse | 72 | 56.7 | 97 | 47.3 | 116 | 55.0 |

| Providing information about enquiries desks | 76 | 59.8 | 83 | 40.5 | 102 | 48.3 |

| Preparing a list of departments of forensic medicine departments that can handle elder abuse | 33 | 26.0 | 94 | 45.9 | 95 | 45.0 |

| Securing a budget for assessment by a forensic practitioner | 22 | 17.3 | 42 | 20.5 | 50 | 23.7 |

| Having opportunities to regularly exchange opinions | 34 | 26.8 | 62 | 30.2 | 80 | 37.9 |

| Other | 3 | 2.4 | 20 | 9.8 | 16 | 7.6 |

| Things needed for future collaboration with forensic practitioners | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Building relationships for easy consultation | 84 | 66.1 | 147 | 64.2 | 145 | 61.2 |

| Clarifying the person in charge and the role of related institutions in handling elder abuse | 56 | 44.1 | 86 | 37.6 | 69 | 29.1 |

| Exchanging opinions face to face | 46 | 36.2 | 129 | 56.3 | 139 | 58.6 |

| Public awareness activities about assessments for elder abuse | 41 | 32.3 | 69 | 30.1 | 76 | 32.1 |

| Other | 3 | 2.4 | 17 | 7.4 | 29 | 12.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toya, M.; Minegishi, S.; Utsuno, H.; Ohta, J.; Namiki, S.; Unuma, K.; Uemura, K.; Sakurada, K. Forensic Characteristics of Physical Elder Abuse and Current Status and Issues of Collaboration between Forensic Medicine Departments and Related Institutions in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215382

Toya M, Minegishi S, Utsuno H, Ohta J, Namiki S, Unuma K, Uemura K, Sakurada K. Forensic Characteristics of Physical Elder Abuse and Current Status and Issues of Collaboration between Forensic Medicine Departments and Related Institutions in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215382

Chicago/Turabian StyleToya, Maiko, Saki Minegishi, Hajime Utsuno, Jun Ohta, Shuuji Namiki, Kana Unuma, Koichi Uemura, and Koichi Sakurada. 2022. "Forensic Characteristics of Physical Elder Abuse and Current Status and Issues of Collaboration between Forensic Medicine Departments and Related Institutions in Japan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215382

APA StyleToya, M., Minegishi, S., Utsuno, H., Ohta, J., Namiki, S., Unuma, K., Uemura, K., & Sakurada, K. (2022). Forensic Characteristics of Physical Elder Abuse and Current Status and Issues of Collaboration between Forensic Medicine Departments and Related Institutions in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215382