Reported Cases of Alcohol Consumption and Poisoning for the Years 2015 to 2022 in Hail, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Biochemical Parameters

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

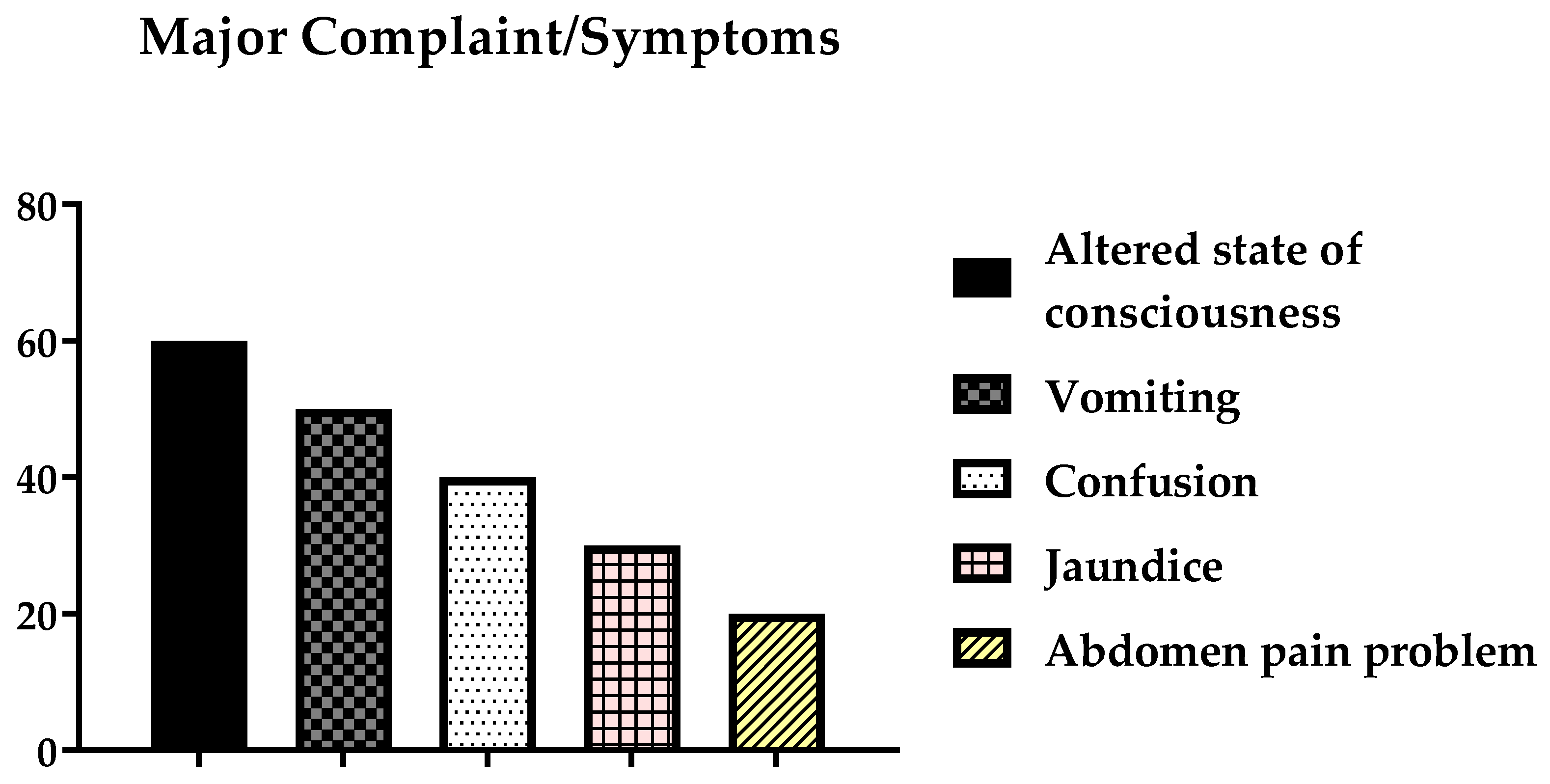

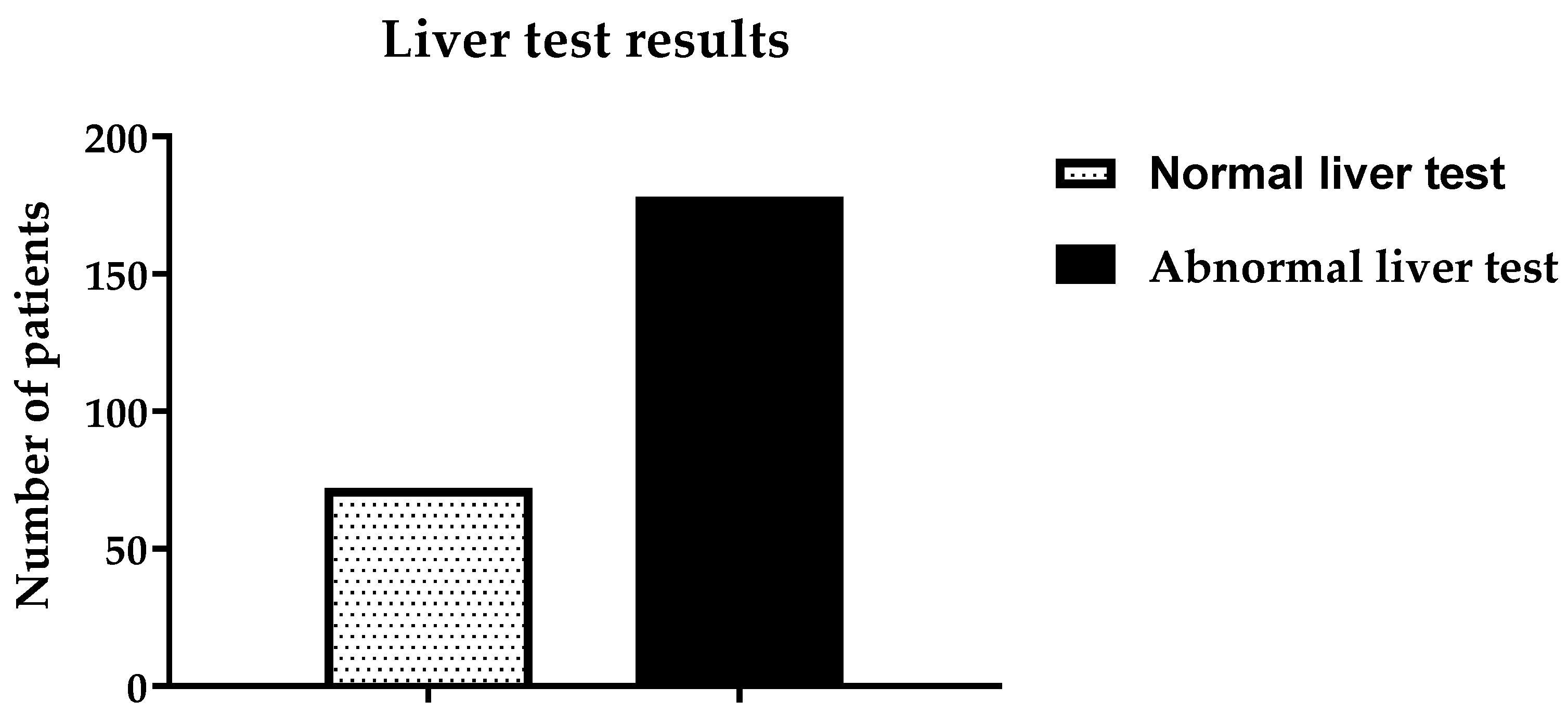

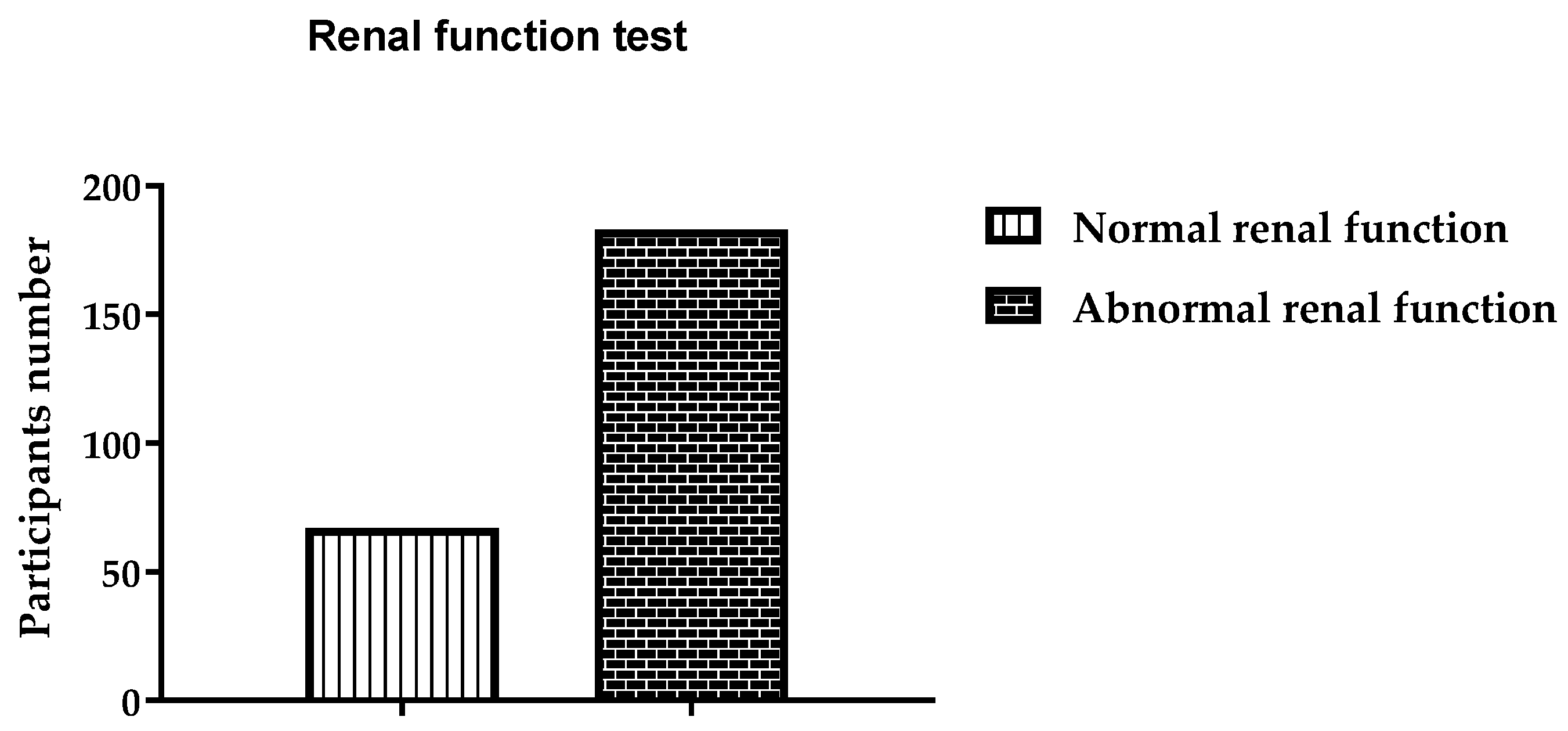

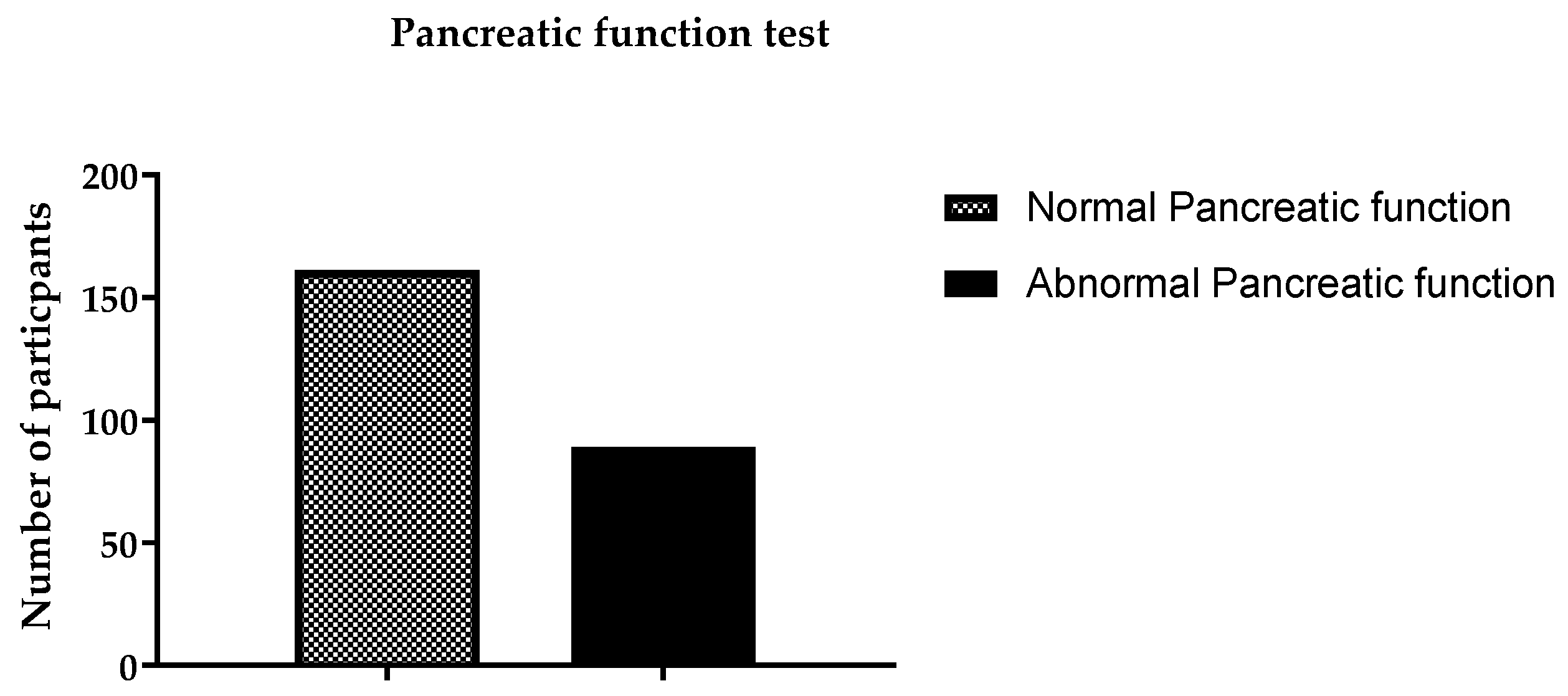

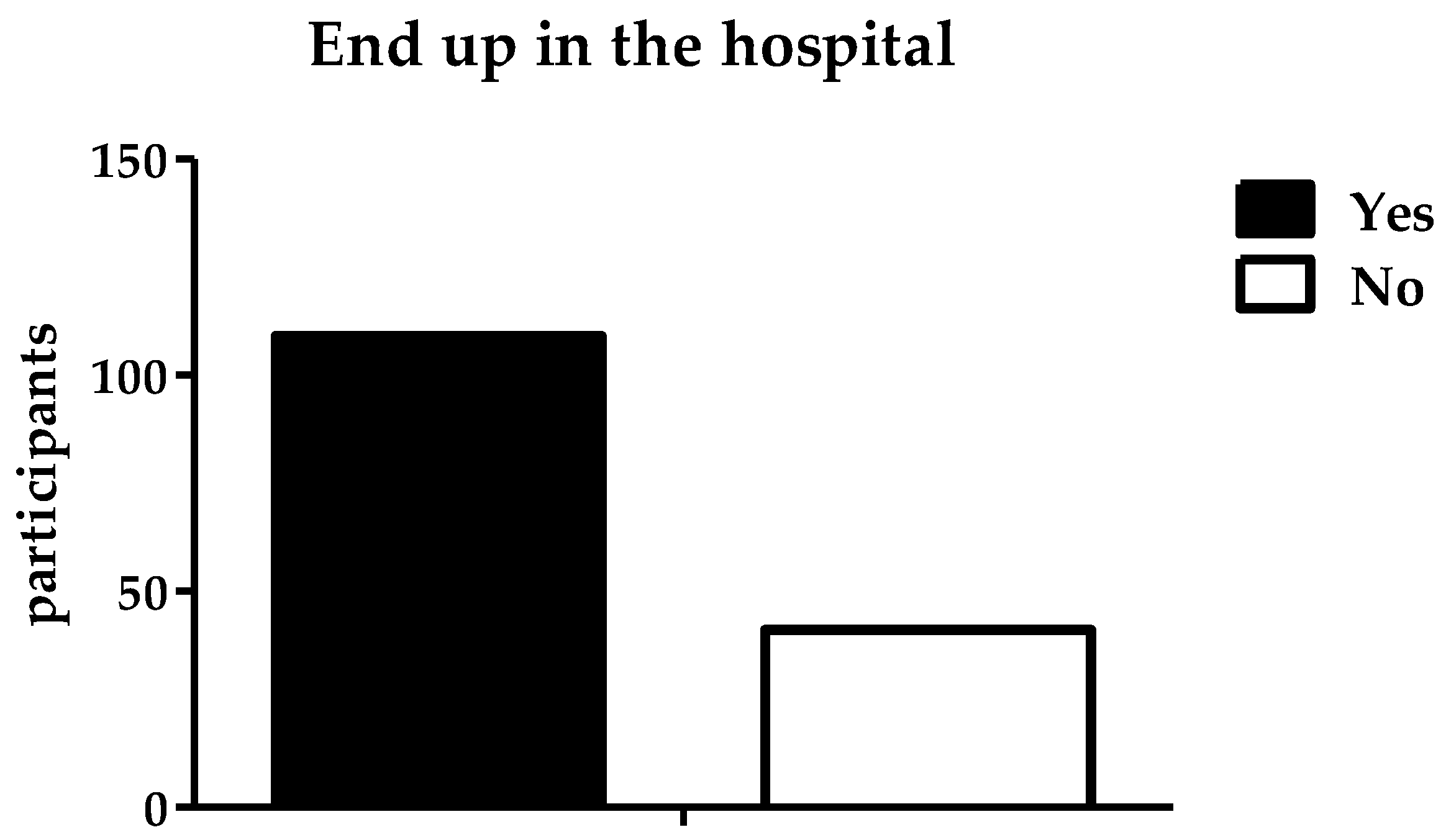

3.1. Group 1

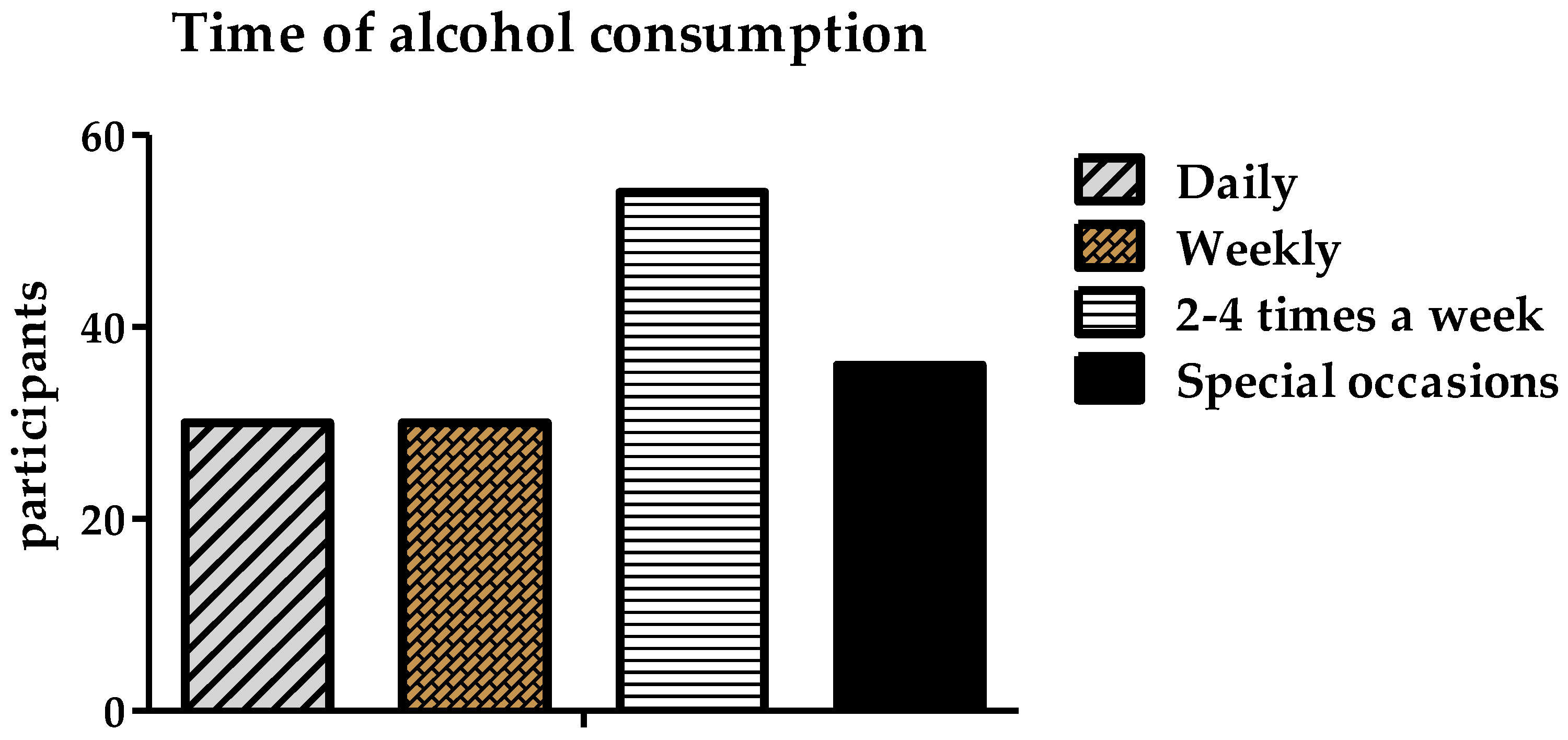

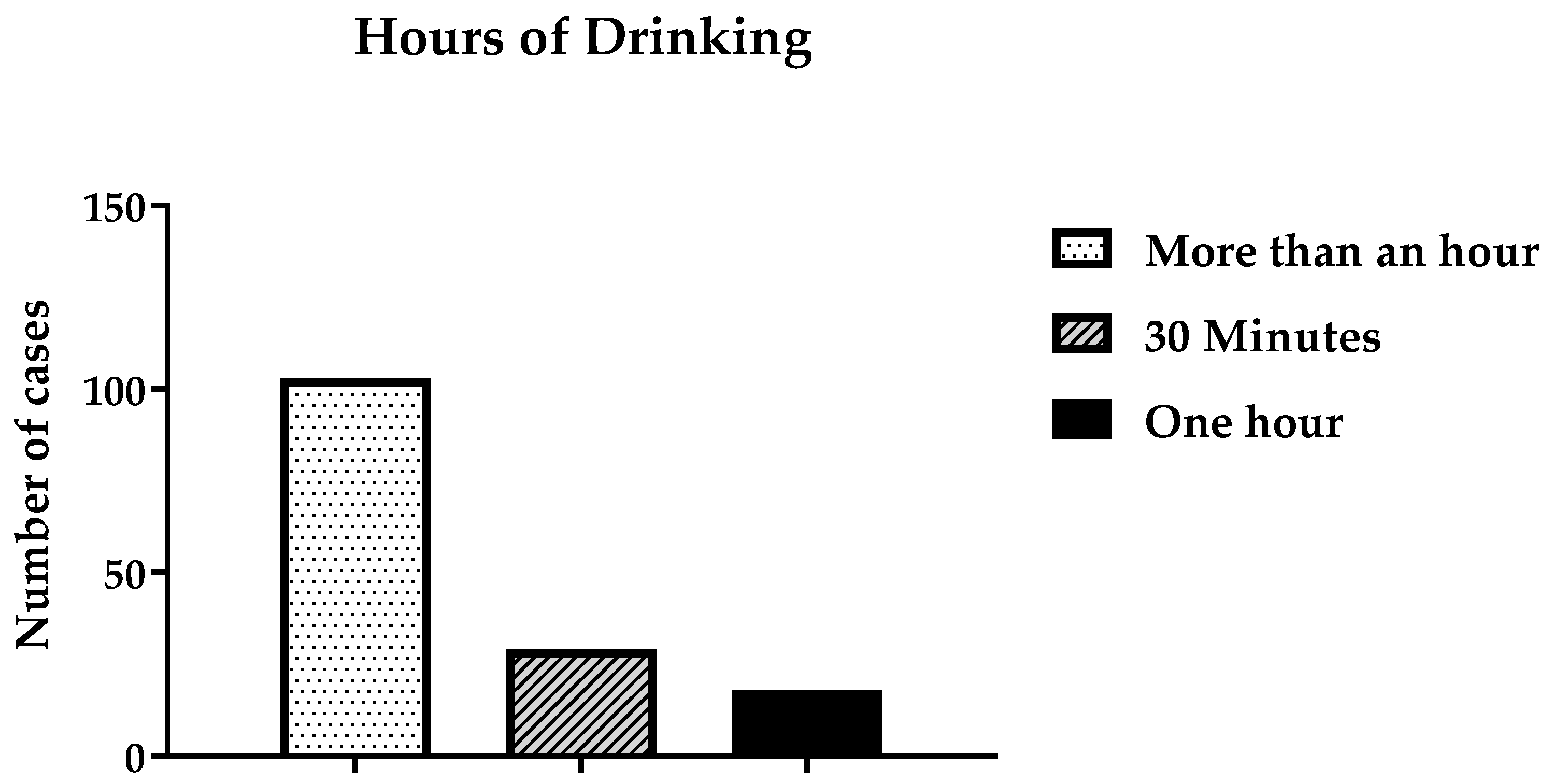

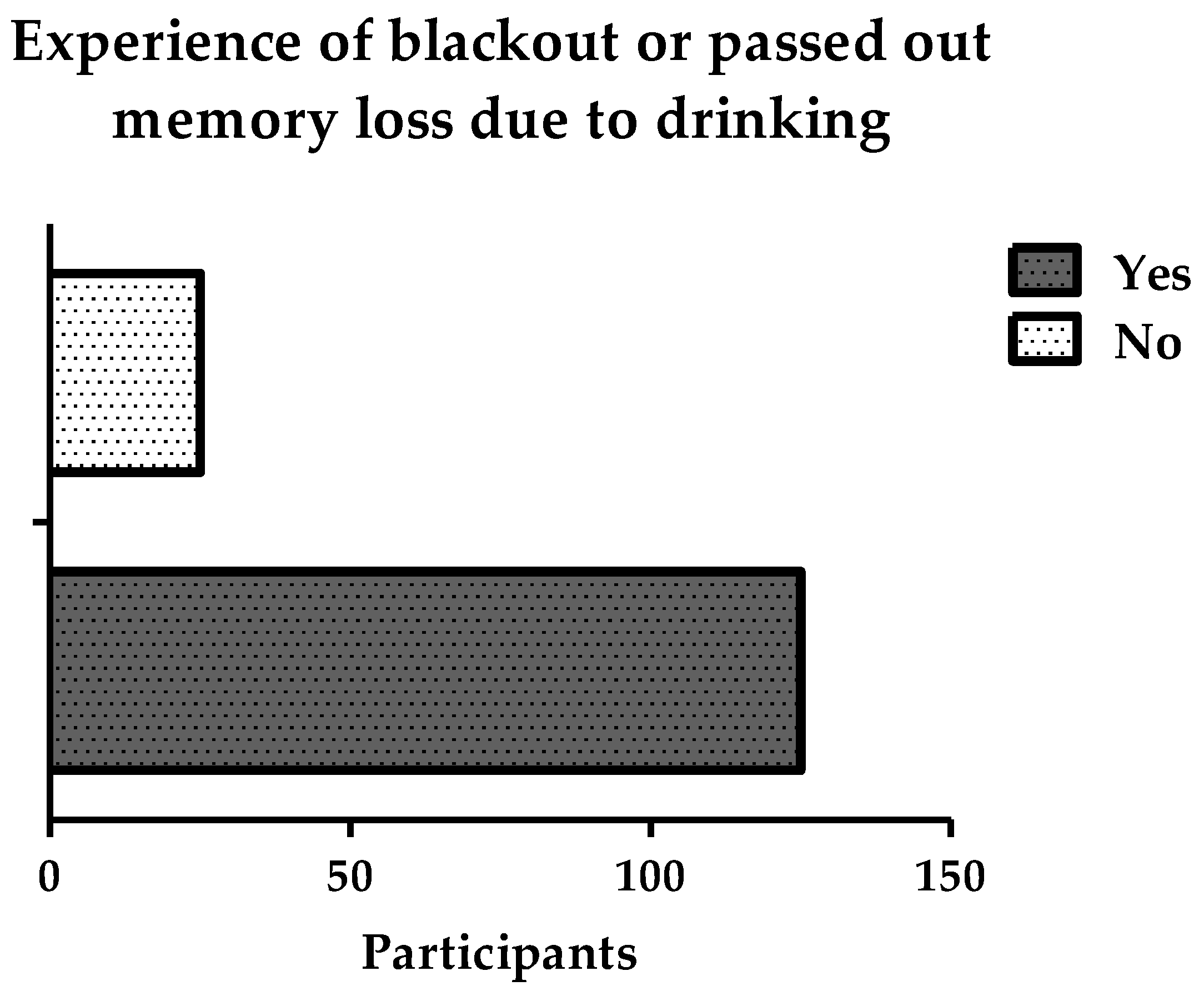

3.2. Group 2

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire and Interview Questions

|

References

- Sudhinaraset, M.; Wigglesworth, C.; Takeuchi, D.T. Social and Cultural Contexts of Alcohol Use: Influences in a Social-Ecological Framework. Alcohol Res. 2016, 38, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bloomfield, K.; Stockwell, T.; Gmel, G.; Rehn, N. International comparisons of alcohol consumption. Alcohol Res. Health 2003, 27, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alhashimi, F.H.; Khabour, O.F.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Al-Shatnawi, S.F. Attitudes and beliefs related to reporting alcohol consumption in research studies: A case from Jordan. Pragmat. Obs. Res. 2018, 9, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luczak, S.E.; Prescott, C.A.; Dalais, C.; Raine, A.; Venables, P.H.; Mednick, S.A. Religious factors associated with alcohol involvement: Results from the Mauritian Joint Child Health Project. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 135, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saquib, N.; Rajab, A.M.; Saquib, J.; AlMazrou, A. Substance use disorders in Saudi Arabia: A scoping review. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2020, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdi, E.; Gawad, T.; Khoweiled, A.; Sidrak, A.E.; Amer, D.; Mamdouh, R. Lifetime prevalence of alcohol and substance use in Egypt: A community survey. Subst. Abus. 2013, 34, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, S.; Kliewer, W.; Ali, M.; Begum, N. Different risk factors are associated with alcohol use versus problematic use in male Pakistani adolescents. Int. J. Psychol. 2020, 55, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbertson, R.; Prather, R.; Nixon, S.J. The role of selected factors in the development and consequences of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Res. Health 2008, 31, 389–399. [Google Scholar]

- White, A.M. Gender Differences in the Epidemiology of Alcohol Use and Related Harms in the United States. Alcohol Res. 2020, 40, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, S.E. Associations Between Socioeconomic Factors and Alcohol Outcomes. Alcohol Res. 2016, 38, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Noel, J.K.; Sammartino, C.J.; Rosenthal, S.R. Exposure to Digital Alcohol Marketing and Alcohol Use: A Systematic Review. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2020, 19 (Suppl. 19), 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, M.A.; Whitehill, J.M. Influence of Social Media on Alcohol Use in Adolescents and Young Adults. Alcohol Res. 2014, 36, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shield, K.D.; Parry, C.; Rehm, J. Chronic diseases and conditions related to alcohol use. Alcohol Res. 2013, 35, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vonghia, L.; Michielsen, P.; Dom, G.; Francque, S. Diagnostic challenges in alcohol use disorder and alcoholic liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 8024–8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikritzhs, T.; Livingston, M. Alcohol and the Risk of Injury. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.A.; Ezzat, B.E. Volatile substance abuse: Experience from Al Amal Hospital, Jeddah. Ann. Saudi Med. 1999, 19, 374–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chinnian, R.R.; Taylor, L.R.; al Subaie, A.; Sugumar, A.; al Jumaih, A.A. A controlled study of personality patterns in alcohol and heroin abusers in Saudi Arabia. J. Psychoact. Drugs 1994, 26, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enstad, F.; Evans-Whipp, T.; Kjeldsen, A.; Toumbourou, J.W.; von Soest, T. Predicting hazardous drinking in late adolescence/young adulthood from early and excessive adolescent drinking—a longitudinal cross-national study of Norwegian and Australian adolescents. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, M.; Zucker, R.A. Reducing underage and young adult drinking: How to address critical drinking problems during this developmental period. Alcohol Res. Health 2010, 33, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wahba, M.A.; Alshehri, B.M.; Hefny, M.M.; Al Dagrer, R.A.; Al-Malki, S.D. Incidence and profile of acute intoxication among adult population in Najran, Saudi Arabia: A retrospective study. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 368504211011339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.A. Substance abuse among patients attending a psychiatric hospital in Jeddah: A descriptive study. Ann. Saudi Med. 1992, 12, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassiony, M. Substance use disorders in Saudi Arabia: Review article. J. Subst. Use 2013, 18, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, C.D.; Patra, J.; Rehm, J. Alcohol consumption and non-communicable diseases: Epidemiology and policy implications. Addiction 2011, 106, 1718–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gender | |

|---|---|

| Male | 244 |

| Female | 6 |

| Mean age in years | 28 (±9.2) |

| No. of participants by age at occurrence of alcohol poisoning (years) | |

| 19–30 | 167 |

| 31–59 | 81 |

| 60 to 75 | 2 |

| Nationality | |

| Saudi | 241 |

| Indian | 8 |

| Non-Saudi | 1 |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 193 |

| Married | 55 |

| Gender | |

|---|---|

| Male | 128 |

| Female | 22 |

| Mean age in years | 31(±10) |

| No. of participants by age at start of alcohol consumption (years) | |

| 19 to 30 | 44 |

| 31 to 59 | 100 |

| 60 to 75 | 6 |

| Education | |

| Elementary | 1 |

| High school | 59 |

| Intermediate | 8 |

| Bachelor | 77 |

| Postgraduate | 5 |

| Nationality | Saudi |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 120 |

| Married | 30 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhaidan, T.; Alzahrani, A.R.; Alamri, A.; Katpa, A.A.; Halabi, A.; Felemban, A.H.; Alsanosi, S.M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.S.; Ayoub, N. Reported Cases of Alcohol Consumption and Poisoning for the Years 2015 to 2022 in Hail, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215291

Alhaidan T, Alzahrani AR, Alamri A, Katpa AA, Halabi A, Felemban AH, Alsanosi SM, Al-Ghamdi SS, Ayoub N. Reported Cases of Alcohol Consumption and Poisoning for the Years 2015 to 2022 in Hail, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215291

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhaidan, Taghreed, Abdullah R. Alzahrani, Abdulwahab Alamri, Abrar A. Katpa, Asma Halabi, Alaa H. Felemban, Safaa M. Alsanosi, Saeed S. Al-Ghamdi, and Nahla Ayoub. 2022. "Reported Cases of Alcohol Consumption and Poisoning for the Years 2015 to 2022 in Hail, Saudi Arabia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215291

APA StyleAlhaidan, T., Alzahrani, A. R., Alamri, A., Katpa, A. A., Halabi, A., Felemban, A. H., Alsanosi, S. M., Al-Ghamdi, S. S., & Ayoub, N. (2022). Reported Cases of Alcohol Consumption and Poisoning for the Years 2015 to 2022 in Hail, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215291