Why Good Employees Do Bad Things: The Link between Pro-Environmental Behavior and Workplace Deviance

Abstract

1. Introduction

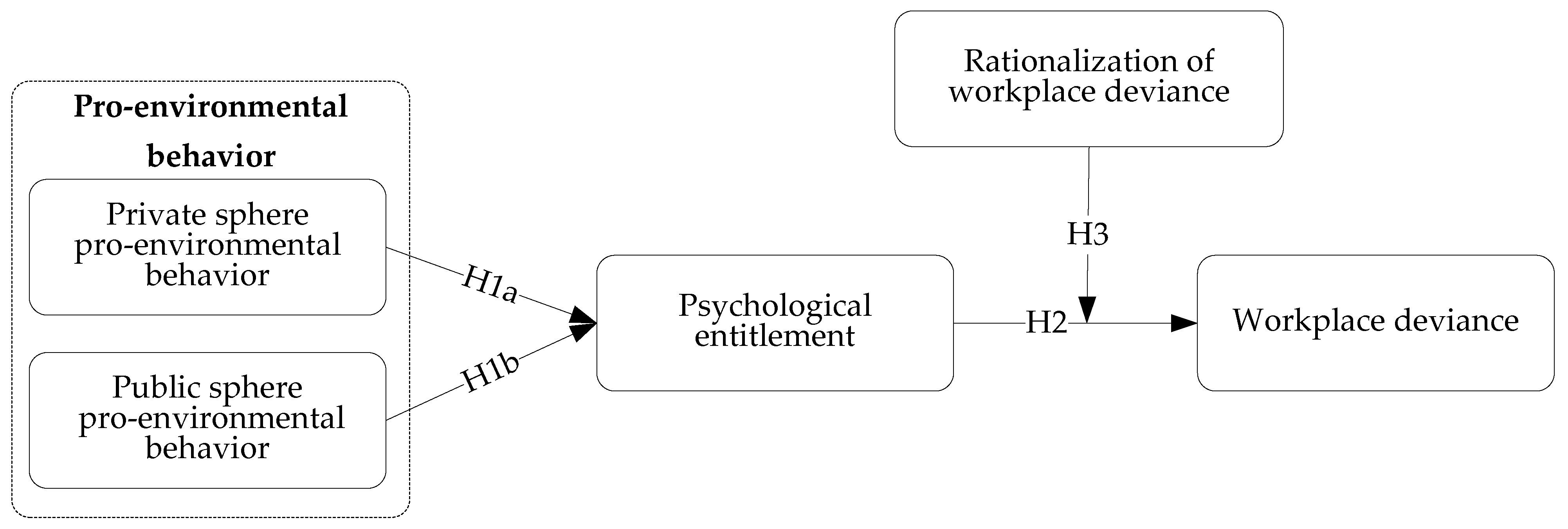

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Moral Licensing Theory

2.2. PEB and Workplace Deviance

2.3. PEB, Psychological Entitlement and Workplace Deviance

2.3.1. PEB and Psychological Entitlement

2.3.2. Psychological Entitlement and Workplace Deviance

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Rationalization of Workplace Deviance

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Reliability and Validity

3.4. Non-Response and Common Method Bias

4. Results

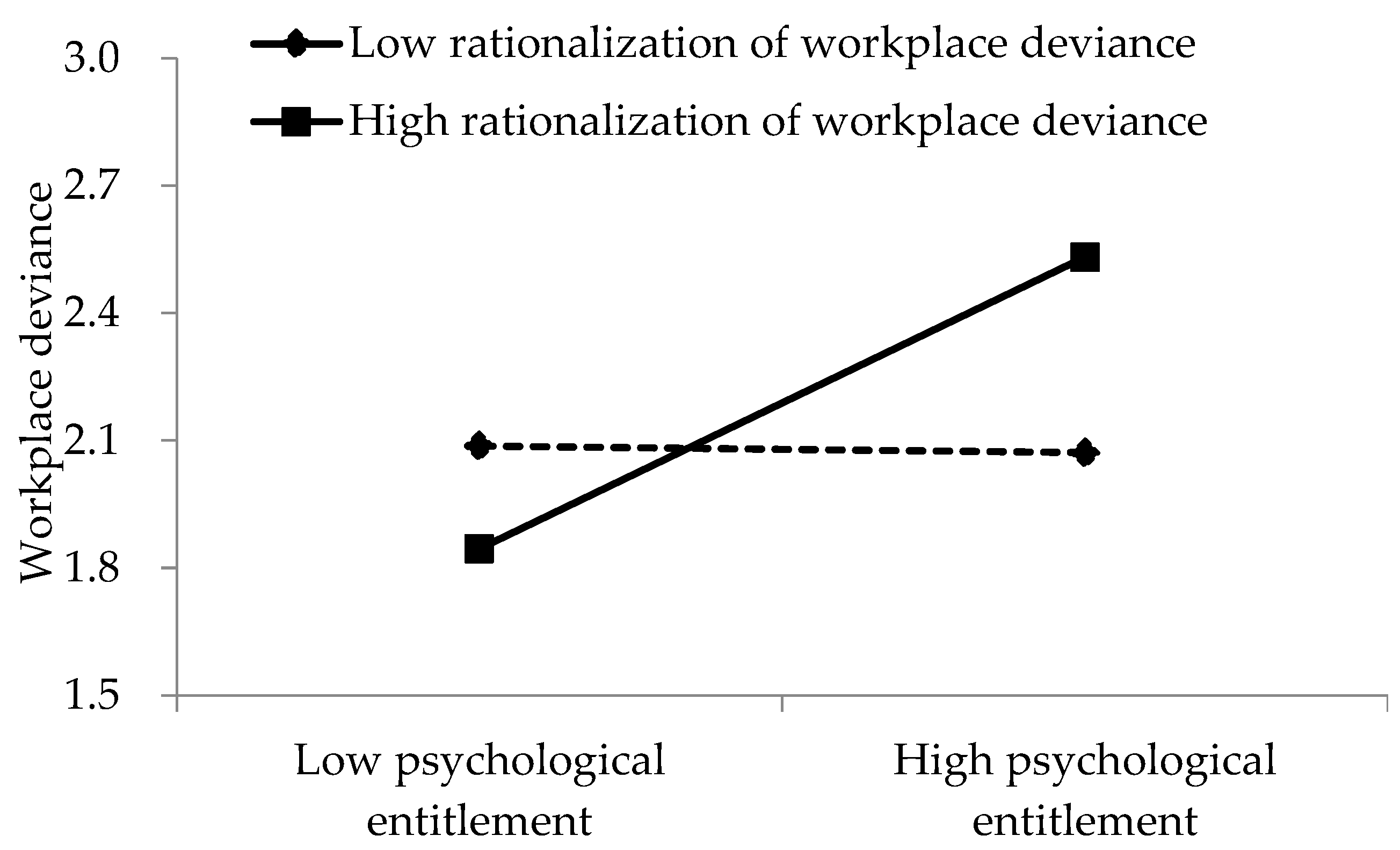

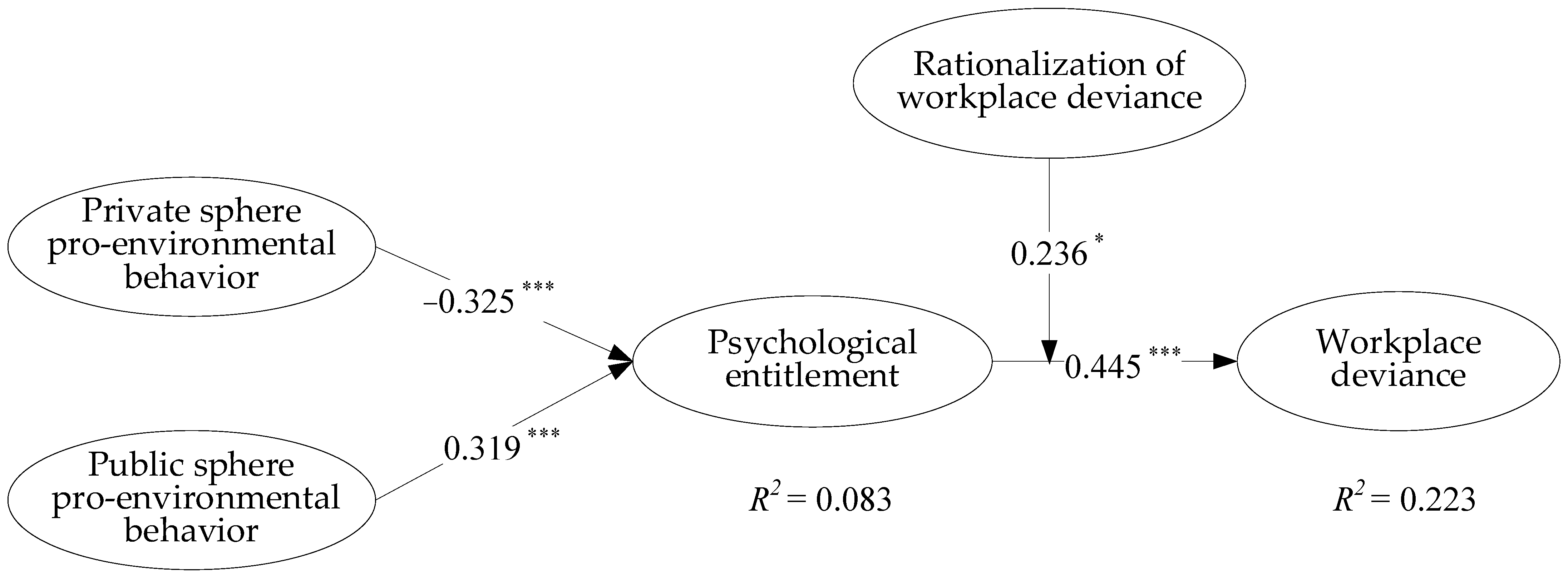

4.1. Hypotheses Testing

4.2. Robust Check

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of the Results

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Measures

References

- Wang, J.; Feng, T. Supply chain ethical leadership and green supply chain integration: A moderated mediation analysis. Int. J. Logist. Res. App. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Yue, T. Who contributed to “corporation green” in China? A view of public- and private-sphere pro-environmental behavior among employees. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 120, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, L.C.; Kouchaki, M. Creative, rare, entitled, and dishonest: How commonality of creativity in one’s group decreases an individual’s entitlement and dishonesty. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1451–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zou, J.; Chen, H.; Long, R. Promotion or inhibition? moral norms, anticipated emotion and employee’s pro-environmental behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Organisational sustainability policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Toward a new measure of organizational environmental citizenship behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 75, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. The relationship between pro-environmental attitude and employee green behavior: The role of motivational states and green work climate perceptions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 7341–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Suo, D. The trickle-down effect of responsible leadership on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors: Evidence from the hotel industry in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Alfaro-Barrantes, P. Pro-environmental behavior in the workplace: A review of empirical studies and directions for future research. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2015, 120, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacasse, K. Can’t hurt, might help: Examining the spillover effects from purposefully adopting a new pro-environmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 2017, 51, 259–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee green behavior: A theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamzadehmir, M.; Sparks, P.; Farsides, T. Moral licensing, moral cleansing and pro-environmental behaviour: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahnel, U.J.J.; Oliver, A.; Michael, W.; Liridon, K.; Karen, H.; Damaris, R.; Hans, S. The power of putting a label on it: Green labels weigh heavier than contradicting product information for consumers’ purchase decisions and post-purchase behavior. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truelove, H.B.; Carrico, A.R.; Weber, E.U.; Raimi, K.T.; Vandenbergh, M.P. Positive and negative spillover of pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and theoretical framework. Glob. Environ. Res. 2014, 29, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagyo, Y. Organizational citizenship behavior as attitude integrity in measurement of individual performance appraisal. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 12, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freis, S.D.; Hansen-Brown, A.A. Justifications of entitlement in grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: The roles of injustice and superiority. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, K.C.; Klotz, A.C.; He, W.; Reynolds, S.J. From good soldiers to psychologically entitled: Examining when and why citizenship behavior leads to deviance. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Chen, C.; Yam, K.C.; Huang, M.; Ju, D. The double-edged sword of leader humility: Investigating when and why leader humility promotes versus inhibits subordinate deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordia, P.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Tang, R.L. When employees strike back: Investigating mediating mechanisms between psychological contract breach and workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1104–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, J. Moral rationalization and the integration of situational factors and psychological processes in immoral behavior. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.H.; Ma, J.; Johnson, R.E. When ethical leader behavior breaks bad: How ethical leader behavior can turn abusive via ego depletion and moral licensing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.T.; Effron, D.A. Psychological license: When it is needed and how it functions. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 43, 115–155. [Google Scholar]

- Monin, B.; Miller, D.T. Moral credentials and the expression of prejudice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Fielding, K.S.; Iyer, A. Experiences of pride, not guilt, predict pro-environmental behavior when pro-environmental descriptive norms are more positive. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Badir, Y.; Kiani, U.S. Linking spiritual leadership and employee pro-environmental behavior: The influence of workplace spirituality, intrinsic motivation, and environmental passion. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, F. Developing an integrated conceptual framework of pro-environmental behavior in the workplace through synthesis of the current literature. Adm. Sci. 2014, 4, 276–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.J.; Robinson, S.L. Development of a measure of workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary-Kelly, A.; Rosen, C.C.; Hochwarter, W.A. Who is deserving and who decides: Entitlement as a work-situated phenomenon. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 42, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, H.A.; Hammerschmidt, M.; Zablah, A.R. Gratitude versus entitlement: A dual process model of the profitability implications of customer prioritization. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitek, E.M.; Jordan, A.H.; Monin, B.; Leach, F.R. Victim entitlement to behave selfishly. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.H.; Wagner, D.T. Spilling outside the box: The effects of individuals’ creative behaviors at work on time spent with their spouses at home. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 841–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.K.; Bonacci, A.M.; Shelton, J.; Exline, J.J.; Bushman, B.J. Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. J. Pers. Assess. 2004, 83, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Schwarz, G.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 154, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.; Harris, K.J. Frustration-based outcomes of entitlement and the influence of supervisor communication. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 1639–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, J.J.; Baumeister, R.F.; Bushman, B.J.; Campbell, W.K.; Finkel, E.J. Too proud to let go: Narcissistic entitlement as a barrier to forgiveness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 894–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armouti-Hansen, J.; Kops, C. This or that? Sequential rationalization of indecisive choice behavior. Theor. Decis. 2017, 84, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S. Towards an understanding of inequity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.P.; Tamborski, M.; Wang, X.; Barnes, C.D.; Mumford, M.D.; Connelly, S.; Devenport, L.D. Moral credentialing and the rationalization of misconduct. Ethics Behav. 2011, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwepker, C.H.; Good, M.C. Salesperson grit: Reducing unethical behavior and job stress. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021, 37, 1887–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.W. Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling: How does sampling affect the validity of research? J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2015, 109, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamie, D.C.; Klaus, U.; Peter, R. Why firms engage in corruption: A top management perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.H.; Wellman, N.; Ashford, S.J.; Lee, C.; Wang, L. Deviance and Exit: The Organizational Costs of Job Insecurity and Moral Disengagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, S.; Shi, J. Linking ethical leadership to employee burnout, workplace deviance and performance: Testing the mediating roles of trust in leader and surface acting. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary-Kelly, S.W.; Vokurka, R.J. The empirical assessment of construct validity. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 16, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method variance in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, J.A.; Buckley, M.R. Estimating trait, method, and error variance: Generalizing across 70 construct validation studies. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regressions: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Loi, T.I.; Kuhn, K.M.; Sahaym, A.; Butterfield, K.D.; Tripp, T.M. From helping hands to harmful acts: When and how employee volunteering promotes workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 944–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.; Bahník, Š.; Kohlová, M.B. Green consumption does not make people cheat: Three attempts to replicate moral licensing effect due to pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Cheng, X.; Tang, Z.; Zhou, K.; Ye, L. Can previous pro-environmental behaviours influence subsequent environmental behaviours? The licensing effect of pro-environmental behaviours. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2016, 10, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.; Fang, W.; Feng, T. Green intellectual capital and green supply chain integration: The mediating role of supply chain transformational leadership. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Feng, T.; Liu, L. The influence of digital transformation on low-carbon operations management practices and performance: Does CEO ambivalence matter? Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Item Code | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private-sphere PEB | PRPE1 | 0.82 | 0.882 | 0.890 | 0.670 |

| PRPE2 | 0.89 | ||||

| PRPE3 | 0.87 | ||||

| PRPE4 | 0.68 | ||||

| Public-sphere PEB | PUPE1 | 0.86 | 0.858 | 0.867 | 0.626 |

| PUPE2 | 0.84 | ||||

| PUPE3 | 0.86 | ||||

| PUPE4 | 0.57 | ||||

| Psychological entitlement | PE1 | 0.76 | 0.837 | 0.876 | 0.649 |

| PE2 | 0.53 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.96 | ||||

| PE4 | 0.90 | ||||

| Rationalization of workplace deviance | RWD1 | 0.77 | 0.795 | 0.833 | 0.503 |

| RWD2 | 0.75 | ||||

| RWD3 | 0.61 | ||||

| RWD4 | 0.60 | ||||

| RWD5 | 0.79 | ||||

| Workplace deviance | WD1 | 0.64 | 0.898 | 0.904 | 0.563 |

| WD2 | 0.76 | ||||

| WD3 | 0.85 | ||||

| WD4 | 0.84 | ||||

| WD5 | 0.89 | ||||

| WD6 | 0.70 |

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.500 | 0.501 | - | |||||||||||

| 2. Marital status | 0.565 | 0.497 | −0.093 | - | ||||||||||

| 3. Dummy of education 1 | 0.583 | 0.494 | 0.075 | −0.325 *** | - | |||||||||

| 4. Dummy of education 2 | 0.088 | 0.284 | 0.082 | 0.108 | −0.367 *** | - | ||||||||

| 5. Age | 3.430 | 0.244 | −0.094 | 0.686 *** | −0.335 *** | 0.103 | - | |||||||

| 6. Tenure | 1.854 | 0.974 | −0.038 | 0.659 *** | −0.389 *** | 0.102 | 0.775 *** | - | ||||||

| 7. Salary | 1.991 | 0.249 | 0.241 *** | 0.132 | −0.078 | 0.380 *** | 0.074 | 0.053 | - | |||||

| 8. Private-sphere PEB | 5.417 | 1.151 | −0.054 | 0.213 ** | 0.016 | −0.020 | 0.261 *** | 0.196 ** | −0.106 | 0.819 | ||||

| 9. Public-sphere PEB | 4.943 | 1.161 | −0.051 | 0.241 *** | −0.137 * | −0.140 * | 0.283 *** | 0.193 ** | −0.039 | 0.534 *** | 0.791 | |||

| 10. Psychological entitlement | 3.188 | 1.555 | 0.082 | 0.087 | −0.089 | −0.159 * | 0.005 | −0.045 | 0.100 | −0.073 | 0.191 ** | 0.806 | ||

| 11. Rationalization of workplace deviance | 3.615 | 1.254 | 0.150 * | −0.064 | −0.017 | −0.043 | −0.030 | −0.071 | 0.085 | −0.194 *** | −0.007 | 0.229 *** | 0.709 | |

| 12. Workplace deviance | 2.302 | 1.032 | 0.157 * | −0.107 | −0.076 | −0.051 | −0.092 | −0.136 * | 0.063 | −0.118 | 0.038 | 0.391 *** | 0.478 *** | 0.750 |

| Variables | Psychological Entitlement | Workplace Deviance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Control variables | |||||

| Gender | 0.094 | 0.092 | 0.159 * | 0.125 | 0.070 |

| Marital status | 0.176 | 0.169 | −0.063 | −0.127 | −0.091 |

| Dummy of education 1 | −0.224 ** | −0.167 * | −0.220 ** | −0.138 | −0.088 |

| Dummy of education 2 | −0.308 *** | −0.247 ** | −0.154 * | −0.042 | −0.007 |

| Age | 0.022 | −0.003 | 0.071 | 0.063 | −0.024 |

| Tenure | −0.239 * | −0.208 | −0.218 | −0.131 | −0.048 |

| Salary | 0.165 * | 0.138 | 0.081 | 0.021 | 0.003 |

| Independent variables | |||||

| Private-sphere PEB | −0.177 * | ||||

| Public-sphere PEB | 0.238 ** | ||||

| Mediator | |||||

| Psychological entitlement (PE) | 0.365 *** | 0.325 *** | |||

| Moderator | |||||

| Rationalization of workplace deviance (RWD) | 0.340 *** | ||||

| Interaction | |||||

| PE × RWD | 0.223 *** | ||||

| R2 | 0.119 | 0.157 | 0.084 | 0.202 | 0.384 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.089 | 0.121 | 0.054 | 0.171 | 0.354 |

| R2 change | 0.039 | 0.117 | 0.182 | ||

| F test for R2 change | 4.009 *** | 4.277 *** | 2.742 ** | 6.539 *** | 12.778 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Shi, H.; Feng, T. Why Good Employees Do Bad Things: The Link between Pro-Environmental Behavior and Workplace Deviance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215284

Zhang Z, Shi H, Feng T. Why Good Employees Do Bad Things: The Link between Pro-Environmental Behavior and Workplace Deviance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215284

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhenglin, Haiqing Shi, and Taiwen Feng. 2022. "Why Good Employees Do Bad Things: The Link between Pro-Environmental Behavior and Workplace Deviance" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215284

APA StyleZhang, Z., Shi, H., & Feng, T. (2022). Why Good Employees Do Bad Things: The Link between Pro-Environmental Behavior and Workplace Deviance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215284