The Impact of Childhood Socioeconomic Status on Adolescents’ Risk Behaviors: The Role of Physiological and Psychological Threats

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Childhood SES and Adolescent Risk Behaviors in Gain and Loss Domains

1.2. The Moderating Role of Threats

2. Experiment 1: The Effect of Childhood SES on Adolescents’ Risk-Seeking Behaviors in Gain and Loss Domains

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Childhood Socioeconomic Status Scale (Childhood SES)

2.3.2. Risk-Seeking Measurement in the Gain and Loss Domains

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Data Analyses

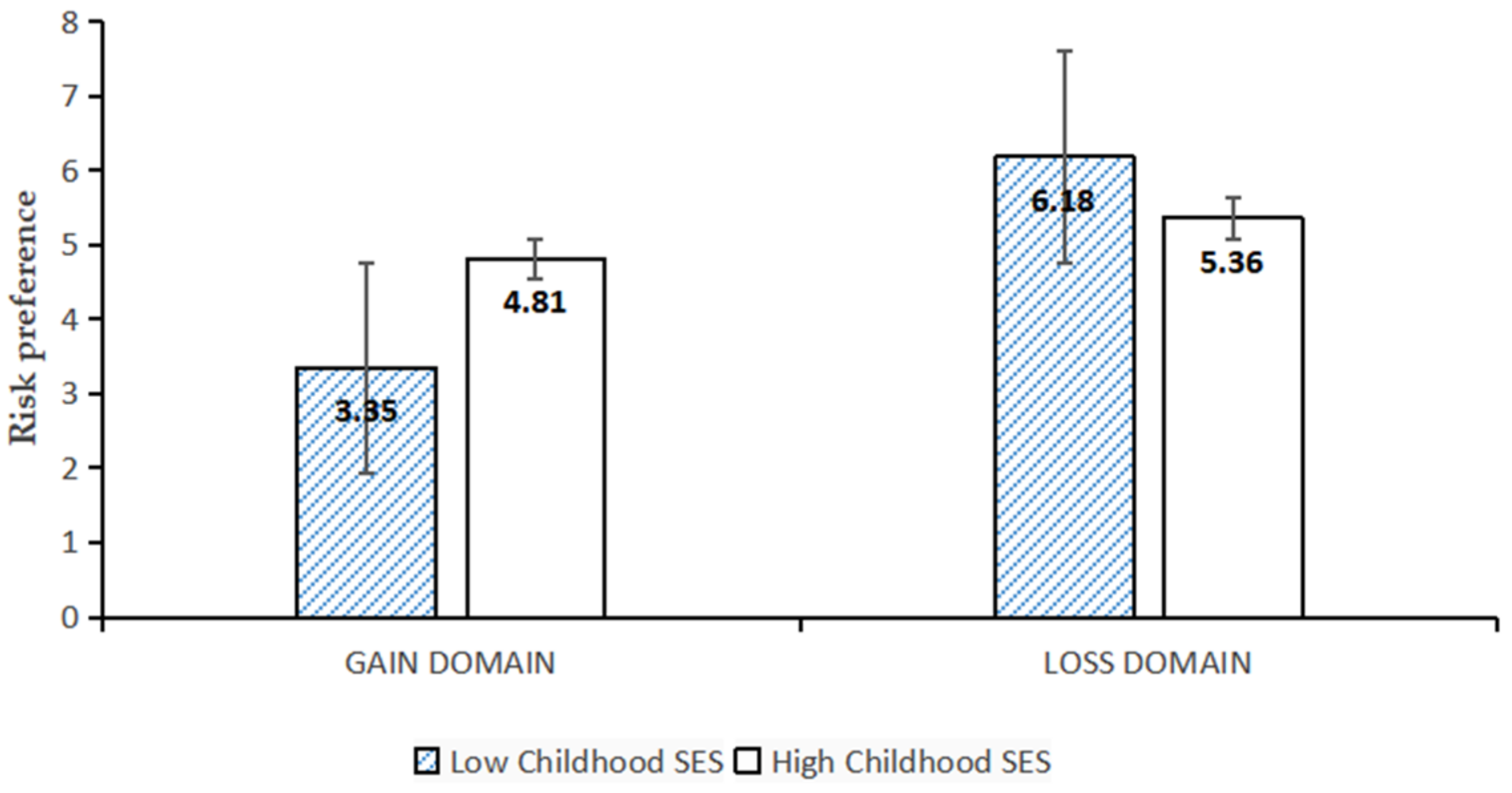

2.6. Results

2.7. Discussion

3. Experiment 2: The Moderating Role of Threats

3.1. Experiment 2a: The Moderating Role of Physiological Threat

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Experimental Design

3.1.3. Materials

3.1.4. Procedure

3.1.5. Data Analyses

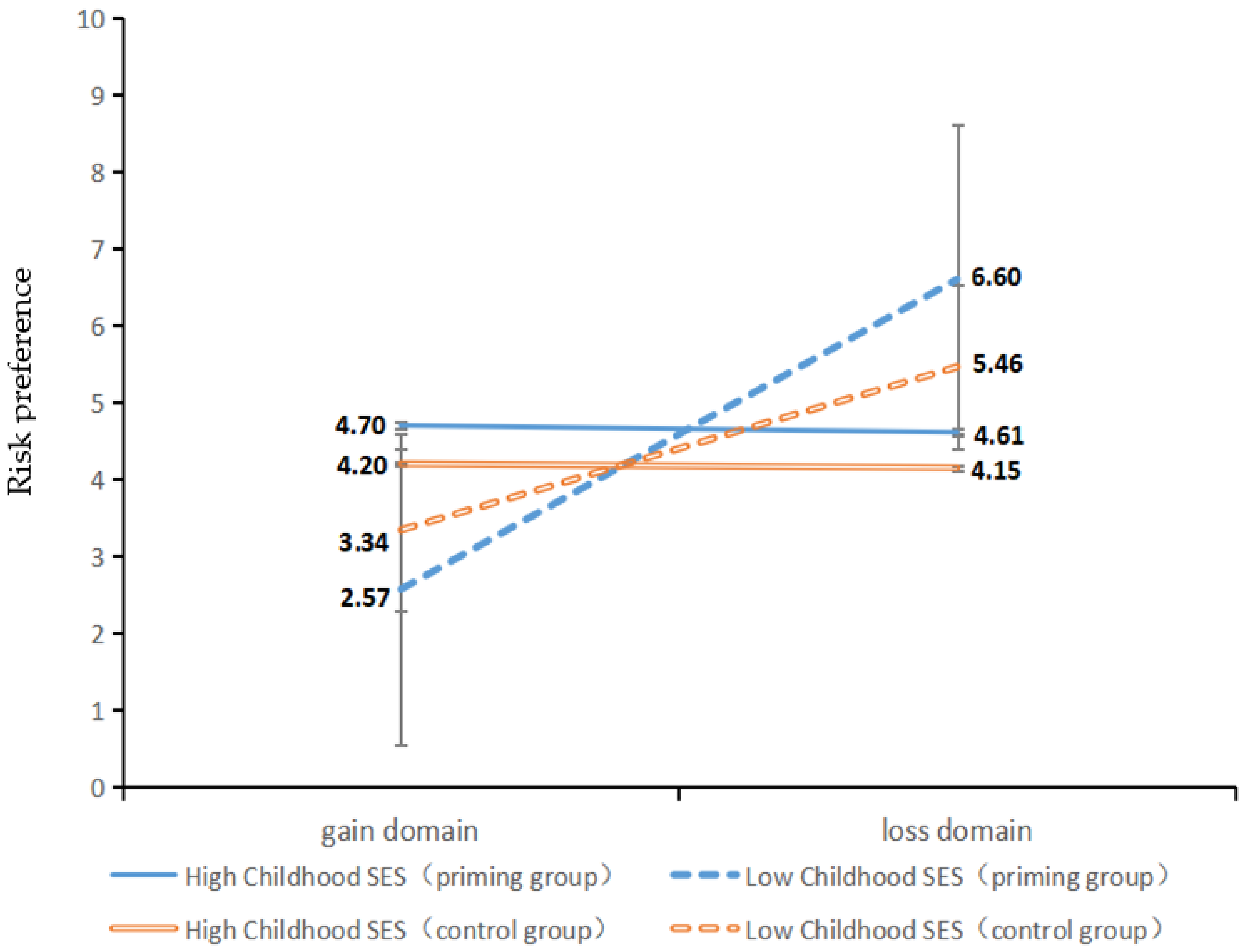

3.1.6. Results

3.2. Experiment 2b: The Moderating Effect of Psychological Threats

3.2.1. Participants

3.2.2. Experimental Design

3.2.3. Materials

3.2.4. Procedure

3.2.5. Data Analyses

3.2.6. Results

4. General Discussion

4.1. Influences of Childhood SES on Adolescents’ Risk Behaviors in Gain and Loss Domains

4.2. Influences of Childhood SES on Adolescent Risk-Seeking Behavior in Gain and Loss Domains under Threat

4.3. Theoretical and Practical Value

4.4. Limitation and Directions of Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, T. The Developmental Cognitive Neural Mechanisms of Adolescents’ Risky Decision Making. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Tian, L.M.; Dong, X.Y. The Relationship between Family Functioning and Adolescent Negative Risk-taking Behavior: A Moderated Mediating Model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2018, 34, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.L.; Tian, L.M.; Guo, J.J. The Associations of Parent-adolescent Relationship with Adolescent Risk-taking Behavior: A Moderated Mediating Model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2019, 35, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Osmont, A.; Camarda, A.; Habib, M.; Cassotti, M. Peers’ Choices Influence Adolescent Risk-taking Especially When Explicit Risk Information is Lacking. J. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 31, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siraj, R.; Najam, B.; Ghazal, S. Sensation Seeking, Peer Influence, and Risk-Taking Behavior in Adolescents. Educ. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.S.; Zhu, D.H.; Sun, G.Q. The Relationship Between Subjective Social Status and Negative Risk-taking Behavior in Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Self-control and Moderating Role of Gender. China J. Health Psychol. 2021, 30, 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Brieant, A.; Herd, T.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Lee, J.; King-Casas, B.; Kim-Spoon, J. Processes linking socioeconomic disadvantage and neural correlates of cognitive control in adolescence. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2021, 48, 100935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Delton, A.W.; Robertson, T.E. The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on risk and delayed rewards: A life history theory approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Guo, Y.Y.; Hu, X.Y.; Shu, S.L.; Li, J. Do lower class individuals possess higher levels of system justification? An ex-amination from the social cognitive perspectives. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2016, 48, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.J.; Kong, Y.Z. In the Perspective of Evolutionary Psychology: Childhood Socioeconomic Status, Values and Green Consumption. Psychol. Explor. 2010, 40, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiihberger, A. The influence of framing on risky decisions: A meta-analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1998, 75, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühberger, A.; Schulte-Mecklenbeck, M.; Perner, J. The effects of framing, reflection, probability, and payoff on risk preference in choice tasks. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1999, 78, 204–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnum, M.E.W.; Kitayama, S. The neuroscience of social class. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 18, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, D.; Jordan, M.R.; Rand, D.G. An uncertainty management perspective on long-run impacts of adversity: The influence of childhood socioeconomic status on risk, time, and social preferences. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 79, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, A.; Reese, H.E.; McNally, R.J.; Philippot, P. Attention training toward and away from threat in social phobia: Effects on subjective, behavioral, and physiological measures of anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 2012, 50, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, C.; Griskevicius, V. Sense of control under uncertainty depends on people’s childhood environment: A life history theory approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 107, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.E.; Prokosch, M.; DelPriore, D.J.; Griskevicius, V.; Kramer, A. Low Childhood Socioeconomic Status Promotes Eating in the Absence of Energy Need. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 27, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.W.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y. The influence of the public crisis on university students’ intertemporal choice: The moderate of subjective socioeconomic status. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 28, 449–456. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J. Childhood experience and the development of reproductive strategics. Psicothema 2010, 22, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Griskevicius, V.; Ackerman, J.M.; Cantú, S.M.; Delton, A.W.; Robertson, T.; Simpson, J.; Thompson, M.E.; Tybur, J.M. When the Economy Falters, Do People Spend or Save? Responses to Resource Scarcity Depend on Childhood Environments. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.F.; Bi, Y.F.; Wang, H.Y. The Effects of Emotions and Task Frames on Risk Preferences in Self Decision Making and An-ticipating Others’ Decisions. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2010, 42, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Gao, X.P. Self-threat Stimuli Capture Attention: Evidence from Inhibition of Return. J. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 40, 296–302. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Cao, Z.Y. The Processing Characteristics of Threatening Information and Its Regulation Strategy. J. Northwest Norm. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2019, 56, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Dan-Glauser, E.S.; Scherer, K.R. The Geneva affective picture database(GAPED): A new 730-picture database focusing on va-lence and normative significance. Behav. Res. Methods 2011, 43, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geng, X.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Yu, H. The Impact of Childhood Socioeconomic Status on Adolescents’ Risk Behaviors: The Role of Physiological and Psychological Threats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215254

Geng X, Xu J, Li Y, Zhang F, Sun X, Yu H. The Impact of Childhood Socioeconomic Status on Adolescents’ Risk Behaviors: The Role of Physiological and Psychological Threats. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215254

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeng, Xiaowei, Jinrong Xu, Yicong Li, Feng Zhang, Xinye Sun, and Hongyang Yu. 2022. "The Impact of Childhood Socioeconomic Status on Adolescents’ Risk Behaviors: The Role of Physiological and Psychological Threats" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215254

APA StyleGeng, X., Xu, J., Li, Y., Zhang, F., Sun, X., & Yu, H. (2022). The Impact of Childhood Socioeconomic Status on Adolescents’ Risk Behaviors: The Role of Physiological and Psychological Threats. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215254