New Dimension on Quality of Life Differences among Older Adults: A Comparative Analysis of Digital Consumption in Urban and Rural Areas of China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Consumption

2.2. Community Services and Consumption Habits

2.3. Quality of Life for Older Adults

2.4. Impact of Pandemic on Quality of Life for Older Adults

2.5. Selective Optimization with Compensation Model

3. Materials and Methods

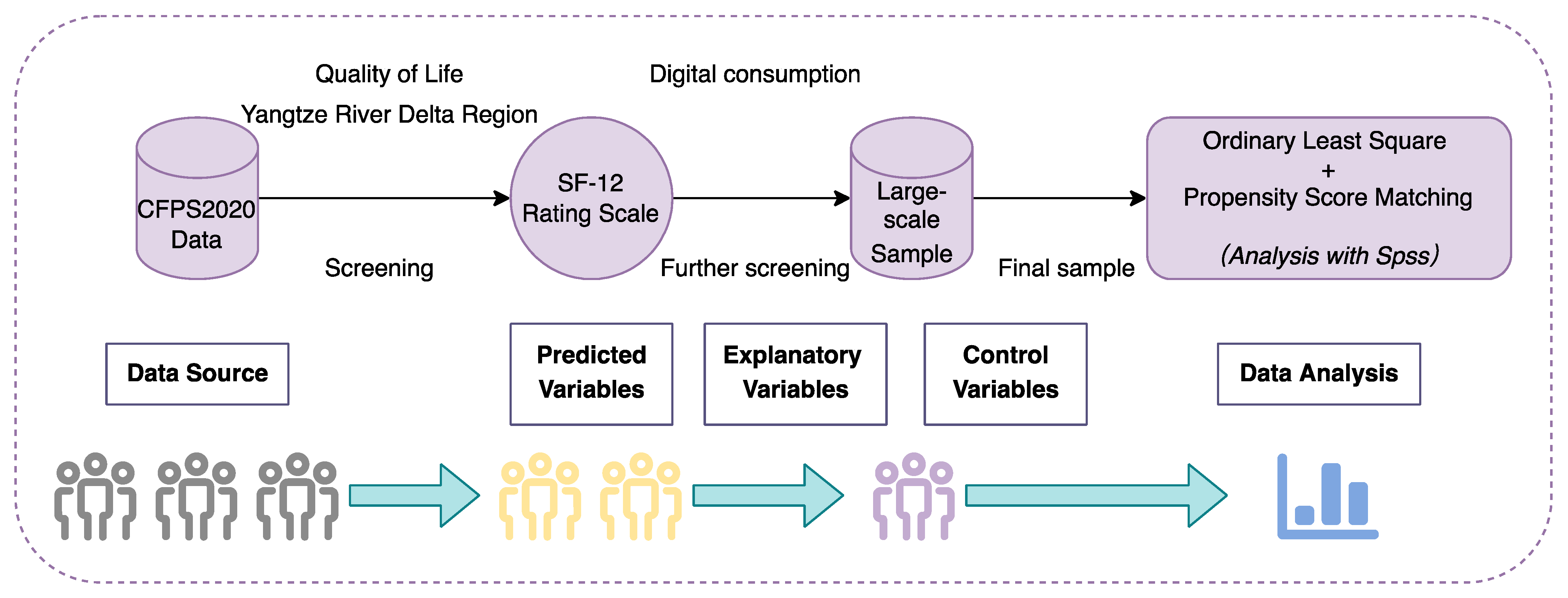

3.1. Quantitative Study of Large-Scale Sample

3.1.1. Study Design

3.1.2. Respondents and Study Site

3.1.3. Measurement

- (1)

- Dependent variables

- (2)

- Independent variables

- (3)

- Control variables

3.1.4. Data Collection

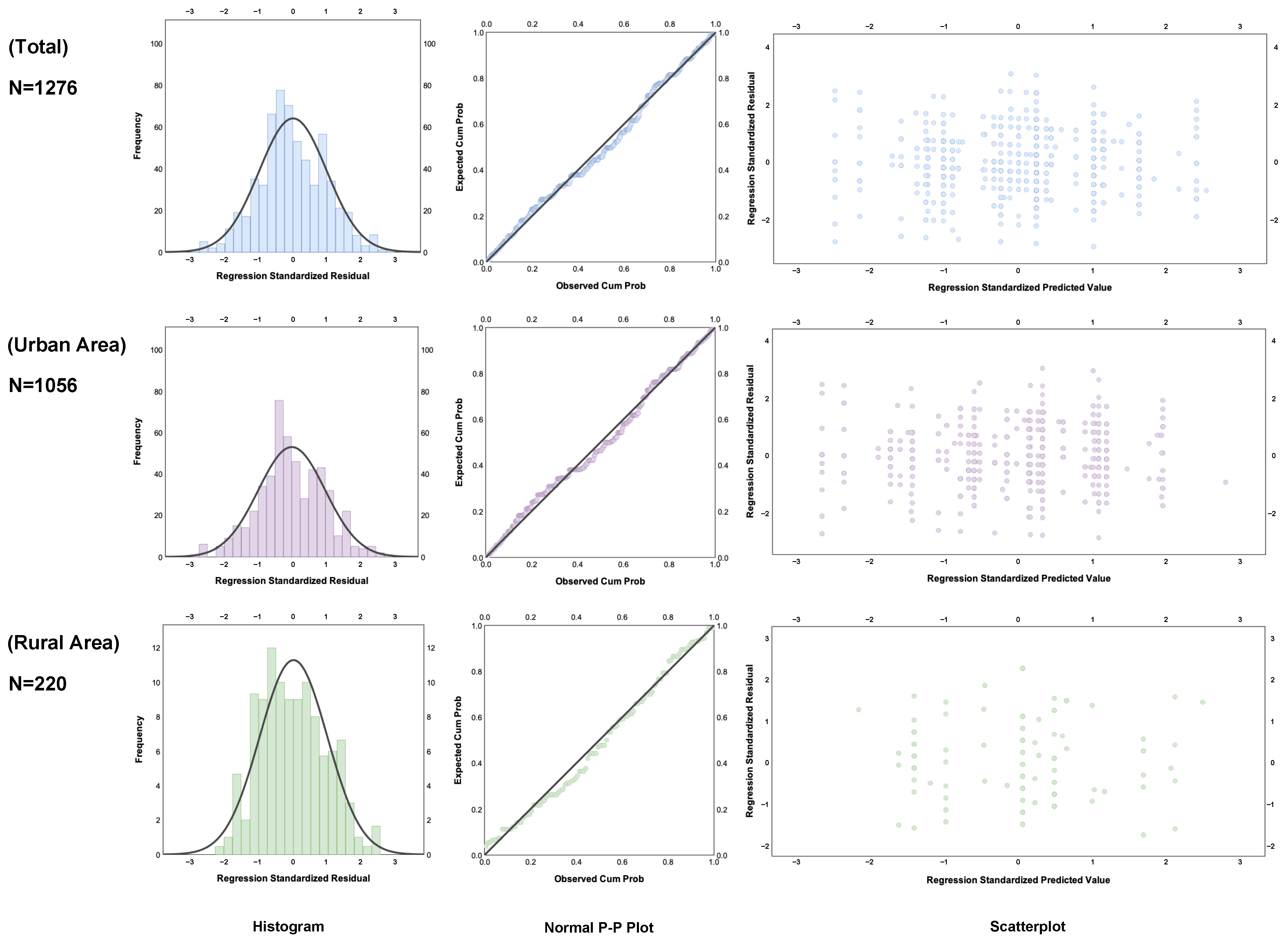

3.1.5. Data Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Study with Small-Scale Sample

3.2.1. Study Design

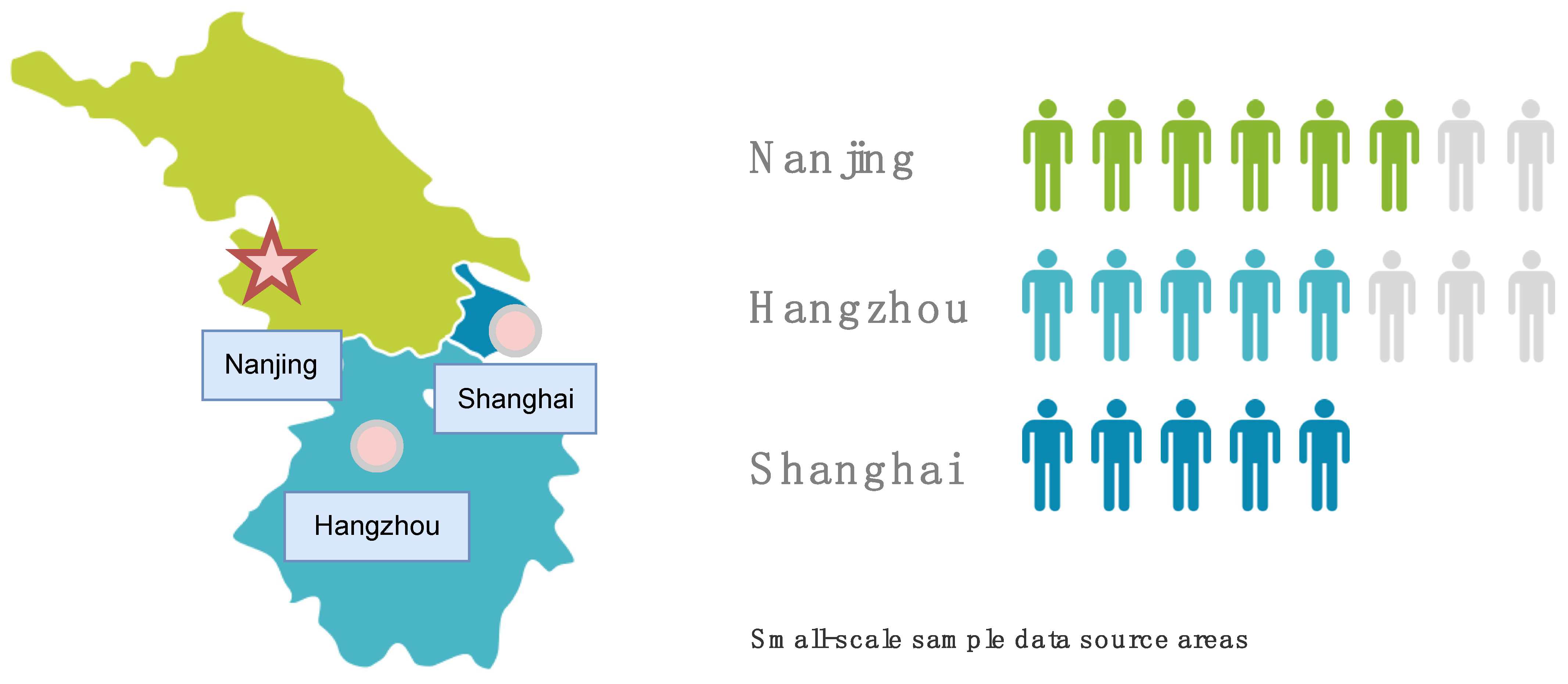

3.2.2. Respondents and Study Site

3.2.3. Measurements

3.2.4. Data Collection

3.2.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Large-Scale Sample

4.1.2. Impact of Digital Consumption on the Quality of Life for Older Adults

4.2. Qualitative Results

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Small-Scale Sample

4.2.2. Semantic Network on Digital Consumption for Older Adults

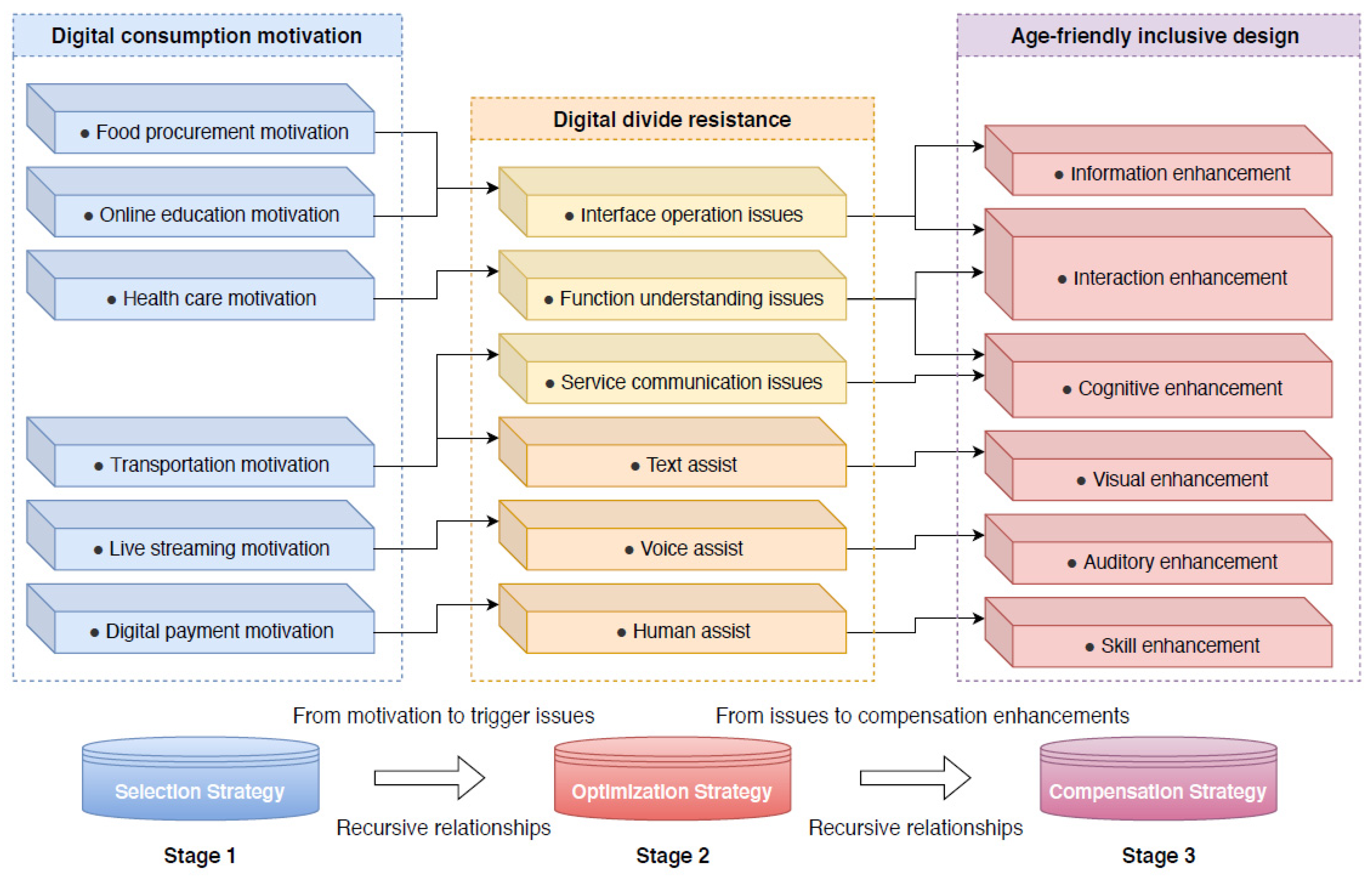

4.2.3. Analysis of Digital Consumption Strategies for Older Adults under the SOC Model

- (1)

- Selection strategy in digital consumption

“Although the range of movement is limited during a pandemic, we can use the online community system to get food provided by the government within one kilometer. We enjoy the better service at the same price.”(64, male, urban)

“Since digitizing my medical records, I can document my diabetes process more visually and better help with treatment. Through a year of use, I have become very proficient in using medical mobile apps. But I am very concerned about the app’s failure because I have not tried other companies’ app offerings.”(60, female, rural)

- (2)

- Optimization strategy in digital consumption

“Presbyopia is so severe that I need to look at my cell phone far away from my eyes, but the distance is too far to operate it. When shopping online, too many items often make myself feel disoriented and dizzy.”(65, female, urban)

“When using map navigation, I often can’t distinguish directions in a short period of time. Since I use a navigation app with a vibration feature, whenever I need to turn at an intersection, I can receive the vibration feedback to help me turn in time. I hope that such vibration cues can be used in other scenarios.”(62, male, urban)

- (3)

- Compensation strategy in digital consumption

“The phone screen is too small and when learning online skills, I often use the auto-read aloud text feature to help me acquire knowledge by ear. Also, I don’t need to keep an eye on home security; the security system will sound an alarm when people walk through.”(70, male, urban)

“Before I was exposed to digital services, I never owned a piano to learn to play because of the cost of space. But now I can play the piano just through online education and electronic simulators, and I can even learn to play any of the playing instruments.”(65, female, urban)

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison of Research Findings

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Appiah-Otoo, I.; Song, N. The impact of ICT on economic growth-Comparing rich and poor countries. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, C.; Zamani, E.D.; Stahl, B.C.; Brem, A. The future of ICT for health and ageing: Unveiling ethical and social issues through horizon scanning foresight. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 155, 119995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedeljko, M.; Bogataj, D.; Kaučič, B.M. The use of ICT in older adults strengthens their social network and reduces social isolation: Literature Review and Research Agenda. IFAC Pap. 2021, 54, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifshitz, R.; Nimrod, G.; Bachner, Y.G. Internet use and well-being in later life: A functional approach. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, E.; Singh, D.; Cruciani, F.; Chen, L.; Hanke, S.; Salvago, F.; Kropf, J.; Holzinger, A. A Conceptual framework for Adaptive User Interfaces for older adults. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PerCom Workshops), Athens, Greece, 19–23 March 2018; pp. 782–787. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, W. Research on Solving Path of Negative Effect of “Information Cocoon Room” in Emergency. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 2022, e1326579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, E. A Precinct Too Far: Turnout and Voting Costs. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2020, 12, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T.A. Census 2020: Understanding the Issues; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-40578-6. [Google Scholar]

- Strausbaugh, L.J. Emerging health care-associated infections in the geriatric population. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001, 7, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pequeno, N.P.F.; de Cabral, N.L.A.; Marchioni, D.M.; Lima, S.C.V.C.; de Lyra, C.O. Quality of life assessment instruments for adults: A systematic review of population-based studies. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williet, N.; Sarter, H.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Adrianjafy, C.; Olympie, A.; Buisson, A.; Beaugerie, L.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Patient-reported Outcomes in a French Nationwide Survey of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamane, A.D.; Witt, E.A.; Su, J. Associations between COPD Severity and Work Productivity, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Health Care Resource Use: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of National Survey Data. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, e191–e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankhotkaew, J.; Chaiyasong, S.; Waleewong, O.; Siengsounthone, L.; Sengngam, K.; Douangvichit, D.; Thamarangsi, T. The impact of heavy drinkers on others’ health and well-being in Lao PDR and Thailand. J. Subst. Use 2017, 22, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.H.; Han, C.H. Health related quality of life in relation to asthma—Data from a cross sectional study. J. Asthma 2018, 55, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, C.; Sacre, H.; Obeid, S.; Salameh, P.; Hallit, S. Validation of the Arabic version of the “12-item short-form health survey” (SF-12) in a sample of Lebanese adults. Arch. Public Health 2021, 79, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimrod, G. Aging Well in the Digital Age: Technology in Processes of Selective Optimization with Compensation. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 75, 2008–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Edelman, L.S.; Tracy, E.L.; Demiris, G.; Sward, K.A.; Donaldson, G.W. Loneliness as a mediator of the impact of social isolation on cognitive functioning of Chinese older adults. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, D. Multiple Linear Regression-Structural Equation Modeling Based Development of the Integrated Model of Perceived Neighborhood Environment and Quality of Life of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study in Nanjing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.-N.; Hu, P.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, Q.-H. Social support as a mediator between depression and quality of life in Chinese community-dwelling older adults with chronic disease. Geriatr. Nurs. 2019, 40, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yin, H.; Meng, X.; Shang, B.; Meng, Q.; Zheng, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, L. Effects of Chinese square dancing on older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Geriatr. Nurs. 2020, 41, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouri, M.J. Eight impacts of the digital sharing economy on resource consumption. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewski, D.; Milewska, B. The Energy Efficiency of the Last Mile in the E-Commerce Distribution in the Context the COVID-19 Pandemic. Energies 2021, 14, 7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.K.; Padhy, R.K.; Dhir, A. Envisioning the future of behavioral decision-making: A systematic literature review of behavioral reasoning theory. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, S.; Oinas, T.; Karhinen, J. Heterogeneity of traditional and digital media use among older adults: A six-country comparison. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, R.P.; Gupta, S.; Patel, P.; Prikshat, V.; Liu, R. Digital consumption and socio-normative vulnerability. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 182, 121808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, V.; Matthies, E.; Thøgersen, J.; Santarius, T. Do online environments promote sufficiency or overconsumption? Online advertisement and social media effects on clothing, digital devices, and air travel consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y. Traditional Values and Political Trust in China. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2018, 53, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rn, D.D.; Machielse, A.; Verté Rn, D.; Dury, S.; De Donder, L.; D-Scope Consortium. Meaning in Life for Socially Frail Older Adults. J. Community Health Nurs. 2019, 36, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Casanova, J.M.; Dura-Perez, E.; Guzman-Parra, J.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.; Mayoral-Cleries, F. Telehealth Home Support During COVID-19 Confinement for Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Mild Dementia: Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Park, Y.-H.; Cho, B.; Lim, K.-C.; Chang, S.J.; Yi, Y.M.; Noh, E.-Y.; Ryu, S.-I. Gender differences in health status, quality of life, and community service needs of older adults living alone. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 83, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, W.; Ashkanani, F. Does COVID-19 change dietary habits and lifestyle behaviours in Kuwait: A community-based cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2020, 25, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, F.D.; Hassan, S.-N.; Alsaif, B.; Zrieq, R. Assessment of the Quality of Life during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qawasmi, J. Selecting a Contextualized Set of Urban Quality of Life Indicators: Results of a Delphi Consensus Procedure. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.S.J.; Mercieca-Bebber, R.; Rutherford, C.; Tait, M.-A.; King, M.T. How is quality of life defined and assessed in published research? Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 2109–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.N.; Pereira, L.N.; da Fé Brás, M.; Ilchuk, K. Quality of life under the COVID-19 quarantine. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 1389–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Basu, S.; Pandit, D. A framework for identifying perceived Quality of Life indicators for the elderly in the neighbourhood context: A case study of Kolkata, India. Qual. Quant. 2022, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, S.; Greenwald, B. Loneliness in the Elderly during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Literature Review in Preparation for a Future Study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 29, S87–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin Kasar, K.; Karaman, E. Life in lockdown: Social isolation, loneliness and quality of life in the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Geriatr. Nur. 2021, 42, 1222–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asqari, M.; Choobdari, A.; Sakhaei, S. The Analysis of Psychological Experiences of the Elderly in the Pandemic of Coronavirus Disease: A Phenomenological Study. Aging Psychol. 2021, 7, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, M.R.; Frielink, N.; Hendriks, A.H.C.; Embregts, P.J.C.M. The General Public’s Perceptions of How the COVID-19 Pandemic Has Impacted the Elderly and Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente-Barroso, C.; Kolotouchkina, O.; Mañas-Viniegra, L. The Enabling Role of ICT to Mitigate the Negative Effects of Emotional and Social Loneliness of the Elderly during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, E.; Nadeau, S.; Higgins, J.; Kehayia, E.; Poldma, T.; Saj, A.; de Guise, E. COVID-19 lockdowns’ effects on the quality of life, perceived health and well-being of healthy elderly individuals: A longitudinal comparison of pre-lockdown and lockdown states of well-being. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 99, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, C.; Carpentieri, G. Quality of life in the urban environment and primary health services for the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic: An application to the city of Milan (Italy). Cities 2021, 110, 103038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-J.; Hsu, Y. Promoting the Quality of Life of Elderly during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri Sheykhangafshe, F.; Fathi Ashtiani, A. The Role of Religion and Spirituality in the Life of the Elderly in the Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Stud. Islam Psychol. 2021, 15, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuoppamäki, S. The Role of Age and Life Course Stage in Digital Consumption; Jyväskylän Yliopisto: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, H.; Işik, K.; Aylaz, R. The effect of anxiety levels of elderly people in quarantine on depression during COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Work Public Health 2021, 36, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.; Monroe-Lord, L.; Carson, A.D.; Jean-Baptiste, A.M.; Phoenix, J.; Jackson, P.; Harris, B.M.; Asongwed, E.; Richardson, M.L. COVID-19 pandemic-related changes in wellness behavior among older Americans. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.; Bouaziz, B.; Trabelsi, K.; Glenn, J.; Zmijewski, P.; Müller, P.; Chtourou, H.; Jmaiel, M.; Chamari, K.; Driss, T.; et al. Applying digital technology to promote active and healthy confinement lifestyle during pandemics in the elderly. Biol. Sport 2020, 38, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, F.; Dai, L.; Chang, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, C.; Li, W. sEMG-Based Identification of Hand Motion Commands Using Wavelet Neural Network Combined with Discrete Wavelet Transform. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 1923–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, P.B.; Baltes, M.M. Successful Aging: Perspectives from the Behavioral Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; ISBN 978-0-521-43582-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Radhakrishnan, K. Evidence on selection, optimization, and compensation strategies to optimize aging with multiple chronic conditions: A literature review. Geriatr. Nur. 2018, 39, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Angerer, P.; Becker, A.; Gantner, M.; Gündel, H.; Heiden, B.; Herbig, B.; Herbst, K.; Poppe, F.; Schmook, R.; et al. Bringing Successful Aging Theories to Occupational Practice: Is Selective Optimization with Compensation Trainable? Work Aging Retire. 2018, 4, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, L.; Csipke, E.; Moniz-Cook, E.; Leung, P.; Walton, H.; Charlesworth, G.; Spector, A.; Hogervorst, E.; Mountain, G.; Orrell, M. The development of the Promoting Independence in Dementia (PRIDE) intervention to enhance independence in dementia. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1615–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, C.; Layte, R. Development and Testing of the UK SF-12. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 1997, 2, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryman, A.; Cramer, D. Quantitative Data Analysis with SPSS 14, 15 & 16: A Guide for Social Scientists; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume XXV, p. 381. ISBN 978-0-415-44089-9. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, J.M.; Kler, J.S.; O’Shea, B.Q.; Eastman, M.R.; Vinson, Y.R.; Kobayashi, L.C. Coping During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study of Older Adults Across the United States. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 643807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friese, S.; Soratto, J.; Pires, D. Carrying Out a Computer-Aided Thematic Content Analysis with ATLAS.ti; MMG Working Paper: Göttingen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aspiration Level, Probability of Success and Failure, and Expected Utility. International Economic Review—Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1468-2354.2008.00494.x (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Padilla-Meléndez, A.; del Aguila-Obra, A.R.; Garrido-Moreno, A. Perceived playfulness, gender differences and technology acceptance model in a blended learning scenario. Comput. Educ. 2013, 63, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G. Age and gender differences in online travel reviews and user-generated-content (UGC) adoption: Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM) with credibility theory. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 428–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Pan, B.; Yin, Z. Pandemic, Mobile Payment, and Household Consumption: Micro-Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 2378–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. Impact of COVID-19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.A. The Oxford Handbook of Moral Development: An Interdisciplinary Perspective; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-0-19-067605-6. [Google Scholar]

- Giansanti, D.; Veltro, G. The Digital Divide in the Era of COVID-19: An Investigation into an Important Obstacle to the Access to the mHealth by the Citizen. Healthcare 2021, 9, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Wang, C.; Bergmann, L. China’s prefectural digital divide: Spatial analysis and multivariate determinants of ICT diffusion. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Type | Contest of Application | Territorial Scale | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yildirim et al. (2021) [47] | Negative | Malatya, Turkey | Regional | During the pandemic, older adults become miserable, tired, and depressed. This leads to a rise in their negative emotions. |

| Guida and Carpentieri (2021) [43] | Negative | Milan, Italy | Urban | Measuring the quality of life of the older adults affected by the coronavirus in Milan in common work scenarios and during the pandemic. |

| Colucci et al. (2022) [42] | Negative | Quebec, Canada | Regional | The blockade during the pandemic led to a decline in the quality of life and well-being of the elderly. |

| Harrison et al. (2021) [48] | Positive | Washington, DC, US | Urban | Minority and non-minority physical activity has decreased since COVID-19, but no change in quality of life was found. |

| Lee and Hsu (2021) [44] | Positive | Taiwan | Regional | The skills of seniors are enhanced through in-home education, thus giving them a new experience. |

| Ammar et al. (2021) [49] | Positive | Magdeburg, German | Regional | Older adults used ICT solutions to improve confidence in health monitoring, improving their quality of life. |

| Sheykhangafshe et al. (2021) [45] | Positive | Tehran, Iran | Urban | Older adults in religious affiliations were more resilient during the pandemic, and more tolerant of the resulting stress and pain, which in turn improved their quality of life. |

| Duan et al. (2021) [50] | Positive | Wuhan, China | Regional | Importance of enhanced vegetable intake and preventive behaviors to improve the quality of life in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Variables | Measurement |

|---|---|

| GH | Respondents’ self-evaluation of general health. (Five-point scale: 1 = Very weak, 5 = Very healthy) |

| PF | Respondents’ self-evaluation of physical function. (Five-point scale: 1 = Very disabled, 5 = Very complete) |

| RP | Respondents’ self-evaluation of role physical. (Five-point scale: 1 = Very slow, 5 = Very fast) |

| BP | Respondents’ self-evaluation of body pain. (Five-point scale: 1 = Very often, 5 = Not at all) |

| VT | Respondents’ self-evaluation of vitality. (Five-point scale: 1 = Very lethargic, 5 = Very active) |

| SF | Respondents’ self-evaluation of social function. (Five-point scale: 1 = Very introverted, 5 = Very outgoing) |

| RE | Respondents’ self-evaluation of role emotion. (Five-point scale: 1 = Very depressed, 5 = Very pleased) |

| MH | Respondents’ self-evaluation of mental health. (Five-point scale: 1 = Very weak, 5 = Very healthy) |

| Variables | Measurement |

|---|---|

| DC1 | Have you ever used digital consumption for life services? (Dichotomous variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes) |

| DC2 | Have you ever used digital consumption for life affairs? (Dichotomous variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes) |

| DC3 | Have you ever used digital consumption for life entertainment? (Dichotomous variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes) |

| Control Variables | Measurement |

|---|---|

| PO | Do you have a pension? (Dichotomous variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes) |

| FS | Do you have financial support from your children? (Dichotomous variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes) |

| GA | Are you willing to participate in group activities? (Dichotomous variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes) |

| IR | Are you good at handling relationships with others? (Dichotomous variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes) |

| CS | Do you have care support from your children? (Dichotomous variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes) |

| FC | Are there aging-friendly facilities close to home? (Dichotomous variables: 0 = No, 1 = Yes) |

| Categories | Questionnaire Description |

|---|---|

| DC1 | |

| 1. Food procurement | Have you ever chosen to get food online? Please describe the experience of using it. |

| 2. Health care | Have you ever remote diagnosis and access to medical records? Please describe the experience of using it. |

| DC2 | |

| 3. Transportation | Have you ever used the electronic reservation system for transportation? Please describe the experience of using it. |

| 4. Digital payment | Have you ever used paperless trading? Please describe the experience of using it. |

| DC3 | |

| 5. Online education | Have you ever used the Internet to learn a skill? Please describe the experience of using it. |

| 6. Live streaming | Have you ever tried to live-stream your life in the network? Please describe the experience of using it. |

| Categories | Variables | Total (N = 1276) | Urban Area (N = 1056) | Rural Area (N = 220) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | ||

| Dependent variable | QoL | 26.92 | 3.34 | 26.88 | 3.30 | 27.13 | 3.55 |

| Independent variable | DC | 0.61 | 0.98 | 0.70 | 1.03 | 0.17 | 0.52 |

| Control variable | PO | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.48 |

| FS | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.36 | |

| GA | 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0.63 | 0.49 | |

| IR | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.10 | 0.30 | |

| CS | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.21 | |

| FC | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.49 | |

| Demographic variable | Gender | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.50 |

| Age | 68.12 | 5.30 | 68.04 | 5.43 | 68.48 | 4.64 | |

| Variables | Total (N = 1276) | Urban Area (N = 1056) | Rural Area (N = 220) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Errors | p | VIF | Standard Errors | p | VIF | Standard Errors | p | VIF | |

| DC1 | 0.49 | 0.095 * | 1.48 | 0.59 | 0.097 * | 1.50 | 0.62 | 0.093 * | 1.50 |

| DC2 | 0.21 | 0.085 * | 1.12 | 0.19 | 0.088 * | 1.11 | 0.80 | 0.082 * | 1.25 |

| DC3 | 0.46 | 0.091 * | 1.77 | 0.48 | 0.095 * | 1.73 | 0.84 | 0.087 * | 2.11 |

| PO | 0.28 | 0.034 ** | 1.00 | 0.31 | 0.050 * | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.017 ** | 1.05 |

| FS | 0.37 | 0.069 * | 1.03 | 0.41 | 0.093 * | 1.04 | 0.92 | 0.044 ** | 1.03 |

| GA | 0.62 | 0.093 * | 2.53 | 0.70 | 0.090 * | 2.59 | 1.38 | 0.095 * | 1.48 |

| IR | 0.21 | 0.078 * | 2.82 | 0.23 | 0.066 * | 2.89 | 0.80 | 0.078 * | 2.15 |

| CS | 0.34 | 0.069 * | 1.33 | 0.33 | 0.069 * | 1.32 | 0.85 | 0.069 * | 2.31 |

| FC | 0.61 | 0.035 ** | 2.68 | 0.69 | 0.034 ** | 2.81 | 1.37 | 0.036 ** | 2.49 |

| R2 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.78 | ||||||

| F | F = 5.62 p = 0.027 ** 5.30 | F = 4.78 p = 0.032 ** 5.43 | F = 6.04 p = 0.022 ** 4.64 | ||||||

| Variables | Status | Treated (N = 220) Control | Control (N = 220) | p | Standard Error (%) | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | |||||

| DC1 | Unmatched | 0.66 | 0.45 | 0.04 ** | 5.25 | 81.25 |

| Matched | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.37 | 2.00 | ||

| DC1 | Unmatched | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 4.75 | 18.75 |

| Matched | 0.36 | 0.20 | 0.70 | 4.00 | ||

| DC1 | Unmatched | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 1.25 | 12.50 |

| Matched | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.89 | 0.75 | ||

| PO | Unmatched | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.02 ** | 1.00 | 18.75 |

| Matched | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.25 | ||

| FS | Unmatched | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.04 ** | 3.25 | 31.25 |

| Matched | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.83 | 2.00 | ||

| GA | Unmatched | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 2.00 | 12.50 |

| Matched | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 1.50 | ||

| IR | Unmatched | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.02 ** | 1.75 | 18.75 |

| Matched | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 1.00 | ||

| CS | Unmatched | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.50 | 6.25 |

| Matched | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.52 | 0.25 | ||

| FC | Unmatched | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 1.00 | 12.50 |

| Matched | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.67 | 0.50 |

| Matching Method | Treated (N = 220) | Control (N = 220) | ATT | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmatched | 27.13 | 27.25 | 0.12 | 0.04 ** |

| Nearest neighbor matching | 27.36 | 27.50 | 0.16 | 0.02 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Wei, W.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y. New Dimension on Quality of Life Differences among Older Adults: A Comparative Analysis of Digital Consumption in Urban and Rural Areas of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215203

Zhang Z, Wei W, Zhu T, Zhou M, Li Y. New Dimension on Quality of Life Differences among Older Adults: A Comparative Analysis of Digital Consumption in Urban and Rural Areas of China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215203

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhizheng, Wentao Wei, Tianlu Zhu, Ming Zhou, and Yajun Li. 2022. "New Dimension on Quality of Life Differences among Older Adults: A Comparative Analysis of Digital Consumption in Urban and Rural Areas of China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215203

APA StyleZhang, Z., Wei, W., Zhu, T., Zhou, M., & Li, Y. (2022). New Dimension on Quality of Life Differences among Older Adults: A Comparative Analysis of Digital Consumption in Urban and Rural Areas of China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215203