A Study on Emotions to Improve the Quality of Life of South Korean Senior Patients Residing in Convalescent Hospitals

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1.

- What is the frequency of emotion types of senior patients residing in convalescent hospitals?

- RQ2.

- What are the contents according to the emotions of senior patients residing in convalescent hospitals?

2. Methods

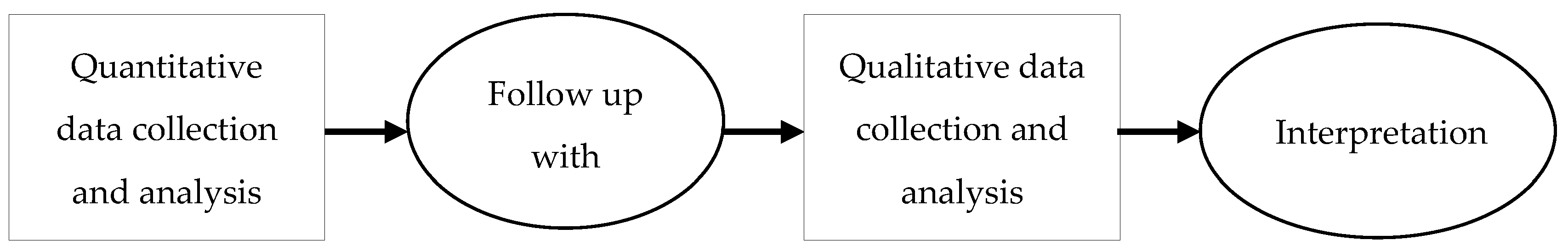

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Subjects

2.3. Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.4. Data Analysis Method

- (1)

- Frequency Analysis

- (2)

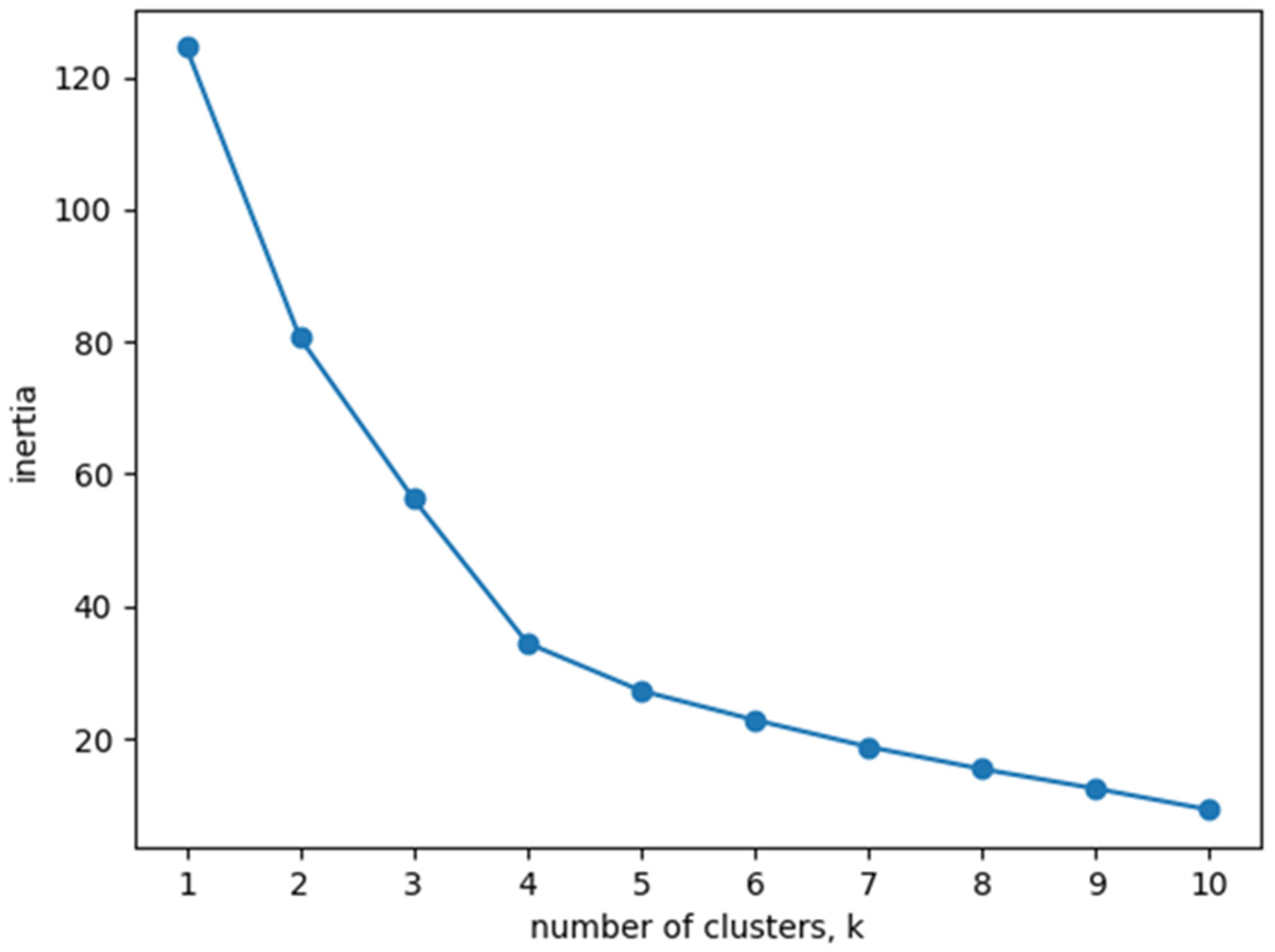

- Clustering of Survey Subjects

2.5. Qualitative Study Procedure

2.6. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Emotion Frequency Analysis

3.1.1. Frequency Analysis

3.1.2. Clustering of Survey Subjects

3.2. Emotion Content Analysis

3.2.1. Current Status of Four Dimensions by Emotion Type

3.2.2. Analysis of Contents According to Emotion Types

Health: Treatment and Recovery

Environment: Life in Narrow Boundaries

Social Relations: Relationships with New People and Family

Psychology: Accepting My Appearance, but It Is Not Easy

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

4.2. Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Health: Treatment and Recovery

| Emotion Type | Contents of Codes | Middle Classification | Code N (46 Total) |

| Joy | Ease of movement, feeling healthy, reduction of pain, good health status | Health status | 12 |

| Smooth bowel movements, smooth movement, comfortable sleep | Daily life function | ||

| Exercise, exercise thought of as rehabilitation | Exercise | ||

| Rehabilitation treatment, good treatment, good nursing | Treatment | ||

| Sorrow | Loss of motor function, uncomfortable movement, difficulty in daily life, poor bowel movements | Difficulties in daily living activities | 10 |

| No appetite, useless rehabilitation exercises | Lack of motivation | ||

| Feeling upset about missing the treatment time, missing the golden time for treatment, injury at a relatively younger age, physical pain | Loss of health due to an accident | ||

| Anger | Insomnia, physical pain | Pain due to illness | 4 |

| Dissatisfaction with the treatment process, dissatisfaction with the treatment result | Dissatisfaction with treatment | ||

| Tranquility | Physical fitness training | Effort for health | 1 |

| Fear | Fall leading to injury, fall, collapse | Accident | 11 |

| Having to take medicines that are thought to be bad, undergoing surgery | Treatment | ||

| Inability to go to a stool by oneself, physical pain, having nightmares, not being able to lead a normal life, worrying about developing dementia, pathological symptoms of the body | Symptoms of illness | ||

| Surprise | Surgery, drug change | Treatment process | 7 |

| Sudden dizziness, palpitations, collapse, inability to get up, knee pain | Sick symptoms | ||

| Hatred | Recognizing that the body is uncomfortable | Uncomfortable body | 1 |

Appendix B. Environment: Life within Narrow Boundaries

| Emotion Type | Contents of Codes | Middle Classification | Code N (28 Total) |

| Joy | Delicious food, eating | Food intake activity | 8 |

| Going out, freedom, everyday life | Everyday life | ||

| Watching food programs, watching TV programs, reading | Hobby | ||

| Sorrow | Uncomfortable environment, absence of caregivers, lack of communication | Discomfort | 6 |

| Lack of money, poor living | Economic difficulty | ||

| High hospital expenses | Hospital expenses | ||

| Anger | Absence of caregivers, uncomfortable environment | Lack of appropriate treatment environment | 6 |

| Unpalatable meals, no going out | Absence of desired daily life | ||

| Tranquility | Having a religion, religious life | Religion | 2 |

| Fear | Shouting of surrounding people | Surrounding people, environment | 1 |

| Surprise | Being humiliated, slamming the door, shouting | Surrounding environment | 3 |

| Hatred | Bad smell, fuss | Hospital environment | 2 |

Appendix C. Social Relations: Relationships with New People and Family

| Emotion Type | Contents of Codes | Middle Classification | Code N (44 Total) |

| Joy | Family members’ visit, increase in family members due to marriage or childbirth, warm family, family members who live well | Relationship with family members | 8 |

| Communication with hospital staff, kind hospital staff, affectionate fellow patients, conversation with fellow patients | Relationship with hospital staff | ||

| Sorrow | Separation from family members, longing for family members, feeling sorry for family members | Attitude toward family members | 17 |

| Family conflict, unhappy family history, and restrictions on meeting with family members due to COVID-19 | Relationship with family members | ||

| Hospital staff not sympathizing, feeling sorry for hospital staff, distrust of hospital staff, an unkind attitude of hospital staff | Attitude toward hospital staff | ||

| Worry about children, sorry for children, regret for not having been good to children, pity for children | Attitude toward children | ||

| Futility after passing on the property, conflict over property inheritance, feeling abandoned by children | Conflicts with children | ||

| Anger | Bad relationships with family members, difficulties with family members | Relationship with children | 6 |

| Quarrels with fellow patients, dissatisfaction with hospital staff, becoming the subject of anger | Conflict in hospital | ||

| High hospital expenses | Hospital expenses | ||

| Tranquility | Grateful for caring persons | Trust in people | 6 |

| Reliable hospital staff, bright hospital staff, good caregivers, kind hospital staff | Depending on people | ||

| Fear | Causing pain to family members | Negative impact on family members | 1 |

| Hatred | Swearing, fighting | Conflict with patients | 2 |

| Contempt | Extortion of hospital money, attitudes of caregivers | Conflict in hospital | 4 |

Appendix D. Psychology: My Appearance That Should Be Accepted although It Is Not Easy to Accept It

| Emotion Type | Contents of Codes | Middle Classification | Code N (41 Total) |

| Joy | Gratitude, a desire to give, positive thoughts, the elevation of mood | Positive attitude | 8 |

| New life in the hospital, a tranquil heart, not getting angry, accepting the situation | Receptive attitude | ||

| Sorrow | Hard life thus far, thinking that there is no future, a situation where I should stay here until death, lack of will to live, despair, resignation | Lethargy | 17 |

| Feeling miserable, sad, feeling pity for oneself, shame, misery, loneliness, depression | Negative attitude toward oneself | ||

| Fear of living long in a sick state, wanting to go home | Worry about the situation | ||

| Reading others’ faces, disappointment | Psychological conflict with others | ||

| Anger | Dissatisfaction, disappointment, and distrust in the hospital | Attitude toward the outside | 6 |

| Sense of shame of sick appearance of oneself, wounded pride, fear of being alone | Inner attitude | ||

| Tranquility | Gratitude, thankfulness, warmth | Attitude toward others | 10 |

| Humility, good character, effort, independent attitude, giving, repaying a favor, hope | Inner attitude |

References

- Ryu, K. The effects of emotion expressivity and ambivalence over emotional expressiveness on the subjective well-being in later life. Korean J. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2010, 24, 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, E.G.; Jo, Y.D. Impact of emotional regulation on the quality of life in elderly people. J. Korean Gerontol. Soc. 2010, 30, 1429–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.-Y.; Choi, J.A. The structure and measurement of Koreans’ emotions. Korean J. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2016, 30, 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, L.S. Emotion-focused therapy. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 2004, 11, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, X.; Ma, X.; Ren, Z. Physical health and quality of life among older people in the context of Chinese culture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Chang, S. A study on relationships among the emotional clarity, emotion regulation style, and psychological well-being. Korean J. Couns. Psychother. 2003, 15, 259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Law Information Center of Ministry of Government Legislation. Available online: http://www.law.go.kr/ (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Poudel, T.M. Health status of ageing people: A case study of Bisharanti Old Aged Home, Mulghat, Dhankuta. Dristikon A Multidiscip. J. 2022, 12, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, A.H.; Karisto, A.; Pitkälä, K.H. Listening to the voice of older people: Dimensions of loneliness in long-term care facilities. Ageing Soc. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, T.G. Emotional, social, and existential loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence and risk factors among Dutch older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2022, 77, e179–e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Kim, K.O. Exploring health-related life changes in the elderly under the COVID-19 pandemic. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2022, 61, 211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, G.S.; Kim, J.S. Change of life of older due to social admission in long-term care hospital. J. Korean Gerontol. Soc. 2017, 37, 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. Universals and cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1971; pp. 207–283. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.H.; Min, K.-H. Emotional experience and emotion regulation in old age. Korean J. Psychol. Gen. 2004, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bendikova, E.; Bartík, P. Selected determinants of seniors’ lifestyle. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2015, 10, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.E.; Choi, J.S.; Choi, S.H.; Yoo, S.Y. The effect of postmigration factors on quality of life among North Korean refugees living in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Lee, M.H. What are the problems (difficulties) experienced by the elderly in Korea? Policy Eval. Manag. 2015, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M.J.; Kim, G.Y. A validation study of the Korean version of the CASP-16. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2022, 42, 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, I.S. Study on family strength and happiness of the pre-elderly and the elderly. Fam. Environ. Res. 2013, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, H.R.; Karppinen, H.; Lehti, T.E.; Knuutila, M.T.; Tilvis, R.; Strandberg, T.; Pitkala, K.H. Secular trends in functional abilities, health and psychological well-being among community-dwelling 75-to 95-year-old cohorts over three decades in Helsinki, Finland. Scand. J. Public Health 2022, 50, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almevall, A.D.; Nordmark, S.; Niklasson, J.; Zingmark, K. Aspects of well-being in very old people: Being in the margins of home and accepting the inevitable. In Proceedings of the 7th ICCHNR Conference, Linnéuniversitetet, Växjö, 21–22 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H.S.; Kim, O.S. Anxiety, depression and health behavior of elderly with chronic diseases. Health Nurs. 2013, 25, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.M.; Jo, E.J. Influence of nursing satisfaction, self-esteem and depression on adjustment of the elderly in long-term care hospital. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2016, 17, 441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Fino, E.; Russo, P.M.; Tengattini, V.; Bardazzi, F.; Patrizi, A.; Martoni, M. Individual differences in emotion dysregulation and social anxiety discriminate between high vs. low quality of life in patients with mild psoriasis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subedi, D. Explanatory sequential mixed method design as the third research community of knowledge claim. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 570–577. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Magai, C.; Consedine, N.S.; Krivoshekova, Y.S.; Kudadjie-Gyamfi, E.; McPherson, R. Emotion experience and expression across the adult life span: Insights from a multimodal assessment study. Psychol. Aging 2006, 21, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-T.; Kang, J.-H. The influence of consumption emotion and satisfaction on intention to re-attend professional soccer. Korean J. Sport Sci. 2006, 17, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.K. A study on web-user clustering algorithm for web personalization. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2011, 12, 2375–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In 5th Berkeley Symp. Math. Statist. Probability; University of California Press: Berkeley/Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1967; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Pheaktra, T.; Lee, J.-H.; Gil, J.-M. A study on research paper classification using keyword clustering. KIPS Trans. Softw. Data Eng. 2018, 7, 477–484. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Y.B.; Lee, H.C.; Jung, S.W. Qualitative Data Analysis; Academy Press: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Technique, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.W. Qualitative Data Analysis: NVivo12 Applications Handing Qualitative Data; Hyeongseol: Gwacheon, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nyun, H. Case study of big data visualization: Centre around the visual representation form. J. Integr. Des. Res. 2014, 13, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.; Lee, W.S.; Shim, J. Exploring Korean middle-and old-aged citizens’ subjective health and quality of life. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menec, V.H.; Chipperfield, J.G. Remaining active in later life: The role of locus of control in seniors’ leisure activity participation, health, and life satisfaction. J. Aging Health 1997, 9, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gringart, E.; Adams, C.; Woodward, F. Older adults’ perspectives on voluntary assisted death: An in-depth qualitative investigation in Australia. OMEGA-J. Death Dying 2022, 00302228221090066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.O.; Gu, M.O. Development and effects of a person-centered fall prevention program for older adults with dementia in long-term care hospitals: For older adults with dementia and caregivers in long-term care hospitals. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2022, 52, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.A. The meaning of relocation among elderly religious sisters. West J. Nurs. Res. 1996, 18, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, A.; Schelling, H.R. Seniors online: Attitudes toward the internet and coping with everyday life. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2018, 37, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Namazi, K.H.; McClintic, M. Computer use among elderly persons in long-term care facilities. Educ. Gerontol. 2003, 29, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ayedee, N. Life under COVID-19 lockdown: An experience of old age people in India. Work. Older People 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, P.S. Whose quality of life is it anyway? Why not ask seniors to tell us about it? Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2000, 50, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kabayama, M.; Tseng, W.; Kamide, K. The presence of neighbours in informal supportive interactions is important for mental health in later life. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 100, 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Choi, H.J. Factors influencing death anxiety in elderly patients in long-term care hospitals. J. Korean Gerontol. Nurs. 2016, 18, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. Dialogue with Erik Erikson; Jason Aronson, Incorporated: Lanham, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, S.B.; Larkin, E. Lessons from Erikson: A look at autonomy across the lifespan. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2006, 4, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, K.W.; Singer, P.A. Chinese seniors’ perspectives on end-of-life decisions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmir, S.; Navipour, H.; Negarandeh, R. Exploring challenges among Iranian family caregivers of seniors with multiple chronic conditions: A qualitative research study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, J.C.A.; Rocha, L.P.; Cavalcanti, F.C.; Marinho, P.E. Relevant functioning aspects and environmental factors for adults and seniors undergoing hemodialysis: A qualitative study. Chronic Illn. 2022, 18, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manju, H.K. Cognitive regulation of emotion and quality of life. J. Psychosoc. Res. 2017, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

| No | Gender | Age | Major Source of Income | The Persons Most Frequently Met Other Than Hospital Personnel after Hospitalization | Reason for Hospitalization (Including Disease Name) | Length of Hospitalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 72 | Farming | Children | Pain in the arm | 2 years |

| 2 | Female | 78 | Other (recipient) | Younger sister/brother | Cerebral infarction | At least 5 years |

| 3 | Female | 88 | Other (unknown) | Son | Unknown | Unknown |

| 4 | Female | 73 | Other (compensation) | Caregiver | Unknown | Unknown |

| 5 | Male | 66 | Other (worker’s compensation) | Children | Cervical spine surgery | At least 5 years |

| 6 | Female | 81 | Family members such as children | Children, friends | Fall at home | Unknown |

| 7 | Male | 78 | Guard’s work | Children, friends | Not remembered | 1 year |

| 8 | Female | 66 | Pension | Younger sister/brother | Cerebral hemorrhage | At least 3 years |

| 9 | Female | 87 | Other (recipient) | Grandson, granddaughter | Rehabilitation after hip surgery | Less than 2 years |

| 10 | Female | 82 | Family members such as children | Children | Stroke, diabetes | 5 years |

| 11 | Female | 86 | Family members such as children | Daughter-in-law | Surgery due to a leg injury | Unknown |

| 12 | Male | 71 | Other (unknown) | None | Stroke | 5 months |

| 13 | Male | 85 | Pension (severance pay) | None | Heart surgery | 20 years |

| 14 | Female | 80 | Other (unknown) | Children | Parkinson’s disease | 7 years |

| 15 | Female | 77 | Pension | Caregiver | Cause unknown | A few days |

| 16 | Male | 73 | Pension | Children | Liver transplant, hernia | 1 year |

| 17 | Male | 86 | Pension, assets, tangerine farming | Caregiver | Cerebral infarction | 1 month |

| 18 | Male | 86 | Family members such as children | Children | Cerebral infarction | At least 5 years |

| 19 | Male | 67 | Self-employment | Church friends | Spinal and limb paralysis due to car accident | At least 7 years |

| 20 | Female | 76 | Family members such as children | Child (eldest son) | Rehabilitation after leg fracture | At least 1 year |

| Study Participant | Emotion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joy | Surprise | Anger | Sorrow | Hatred | Fear | Contempt | Tranquility | |

| 1 | 1.25225 | 0.89189 | 0.18919 | 1.61261 | 0.00000 | 0.78378 | 0.00000 | 1.25225 |

| 2 | 2.71429 | 0.00000 | 4.62698 | 0.58730 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 |

| 3 | 0.00000 | 0.41270 | 0.00000 | 8.25397 | 0.00000 | 0.44444 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 |

| 4 | 1.12121 | 0.02273 | 0.00000 | 4.62879 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.40530 |

| 5 | 0.69697 | 0.37879 | 4.16667 | 1.31818 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 1.30303 |

| 6 | 1.97619 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.32143 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 2.64286 |

| 7 | 2.12121 | 0.00000 | 2.04545 | 1.08333 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.07955 | 0.69697 |

| 8 | 2.55758 | 0.32727 | 0.29091 | 2.64242 | 0.60606 | 0.33333 | 0.00000 | 0.96364 |

| 9 | 1.39247 | 0.10753 | 0.93190 | 2.25806 | 0.04301 | 0.60215 | 0.53405 | 0.67563 |

| 10 | 1.08835 | 0.43373 | 0.70683 | 3.20482 | 0.01205 | 0.01205 | 0.01205 | 0.01205 |

| 11 | 1.36735 | 2.17347 | 0.00000 | 1.62585 | 0.02041 | 0.77551 | 0.02041 | 0.02041 |

| 12 | 2.84459 | 0.01351 | 0.78378 | 0.79279 | 0.00000 | 0.01351 | 0.60811 | 0.93694 |

| 13 | 1.86404 | 0.02193 | 0.88158 | 1.25877 | 0.19737 | 0.65351 | 0.01316 | 0.38596 |

| 14 | 1.54000 | 0.36889 | 0.15111 | 3.74222 | 0.00000 | 0.08889 | 0.00000 | 0.22667 |

| 15 | 0.49383 | 0.00000 | 1.34568 | 3.60802 | 0.00000 | 0.33951 | 0.00000 | 0.19753 |

| 16 | 3.03226 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.78495 | 0.00000 | 0.17742 | 0.00000 | 0.38710 |

| 17 | 1.83987 | 0.00000 | 1.43791 | 2.26797 | 0.00000 | 0.26797 | 0.00000 | 0.14706 |

| 18 | 1.78947 | 0.00000 | 0.49123 | 3.02193 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 |

| 19 | 0.42593 | 0.30093 | 1.03241 | 2.46759 | 0.19907 | 0.40741 | 0.07407 | 0.43981 |

| 20 | 0.24883 | 0.14554 | 0.24883 | 3.13615 | 0.06103 | 0.09859 | 0.11033 | 0.56103 |

| No. | Division | Emotion | Category Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| 1 | Health: Treatment and recovery | Health status, daily life functions, exercise, treatment | Difficulty in daily life, lack of motivation, loss of health due to accident | Pain due to the disease, dissatisfaction with treatment | Effort for health | Accidents, treatment, symptoms appearing due to the disease | Treatment process, painful symptoms | Uncomfortable body | 16 | |

| 2 | Environment: Life within narrow boundaries | Food intake activities, daily life, hobbies | Discomfort, financial difficulties, hospital costs | Discomfort, lack of an appropriate treatment environment, and lack of desired routines | Religion | Surrounding people, environment | Surrounding environment | Surrounding environment | 13 | |

| 3 | Social Relations: Relationships with new people and family | Relationship with family members, relationship with hospital staff | Attitude toward family members, relationship with family members, attitude toward hospital staff, conflict with children | Relationship with family members, conflicts in the hospital | Trust in people, dependence on people | Negative impact on family members | Conflict with patients | Conflict in hospital | 13 | |

| 4 | Psychology: Sorrow that can hardly be accepted | Positive attitude, receptive attitude | Lethargy, negative attitude toward self, worry about the situation, psychological conflict with others | Attitude toward the outside, inner attitude | Attitude toward others, inner attitude | 10 | ||||

| Category Total | 11 | 14 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 52 | |

| Study Participant | Emotion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joy | Surprise | Anger | Sorrow | Hatred | Fear | Contempt | Tranquility | |

| 1 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 6 |

| 2 | 8 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 7 | 15 | 0 | 13 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 8 | 19 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| 9 | 19 | 1 | 13 | 34 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 10 | 14 | 7 | 14 | 44 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | 36 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 9 |

| 13 | 26 | 1 | 9 | 19 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| 14 | 20 | 4 | 2 | 45 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 15 | 5 | 0 | 11 | 32 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| 16 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 17 | 16 | 0 | 12 | 19 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 18 | 13 | 0 | 4 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | 6 | 4 | 13 | 34 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| 20 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 47 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| Total | 256 | 42 | 134 | 424 | 17 | 45 | 22 | 85 |

| Number | Support | Emotion and Emotion Pair |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Sorrow |

| 2 | 0.95 | Joy |

| 3 | 0.95 | Sorrow, Joy |

| 4 | 0.85 | Tranquility |

| 5 | 0.85 | Sorrow, Tranquility |

| 6 | 0.85 | Tranquility, Joy |

| 7 | 0.85 | Sorrow, Tranquility, Joy |

| 8 | 0.75 | Joy, Anger |

| 9 | 0.75 | Sorrow, Anger |

| 10 | 0.75 | Anger |

| 11 | 0.75 | Sorrow, Joy, Anger |

| 12 | 0.7 | Fear |

| 13 | 0.7 | Sorrow, Fear |

| 14 | 0.65 | Sorrow, Tranquility, Joy, Anger |

| 15 | 0.65 | Sorrow, Fear, Joy |

| 16 | 0.65 | Sorrow, Tranquility, Fear |

| 17 | 0.65 | Sorrow, Tranquility, Anger |

| 18 | 0.65 | Tranquility, Fear, Joy |

| 19 | 0.65 | Tranquility, Anger |

| 20 | 0.65 | Tranquility, Joy, Anger |

| 21 | 0.65 | Tranquility, Fear |

| 22 | 0.65 | Surprise |

| 23 | 0.65 | Sorrow, Surprise |

| 24 | 0.65 | Fear, Joy |

| 25 | 0.65 | Sorrow, Tranquility, Fear, Joy |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Rhee, J.; Lee, S.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, J.; Yoo, Y.; Kim, H.; So, H.; Park, J. A Study on Emotions to Improve the Quality of Life of South Korean Senior Patients Residing in Convalescent Hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114480

Kim A, Kim Y, Rhee J, Lee S, Jeong Y, Lee J, Yoo Y, Kim H, So H, Park J. A Study on Emotions to Improve the Quality of Life of South Korean Senior Patients Residing in Convalescent Hospitals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114480

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Aeju, Yucheon Kim, Jongtae Rhee, Songyi Lee, Youngil Jeong, Jeongeun Lee, Youngeun Yoo, Haechan Kim, Hyeonji So, and Junhyeong Park. 2022. "A Study on Emotions to Improve the Quality of Life of South Korean Senior Patients Residing in Convalescent Hospitals" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114480

APA StyleKim, A., Kim, Y., Rhee, J., Lee, S., Jeong, Y., Lee, J., Yoo, Y., Kim, H., So, H., & Park, J. (2022). A Study on Emotions to Improve the Quality of Life of South Korean Senior Patients Residing in Convalescent Hospitals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114480