Menstrual and Reproductive Factors for Gastric Cancer in Postmenopausal Women: The 2007–2020 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

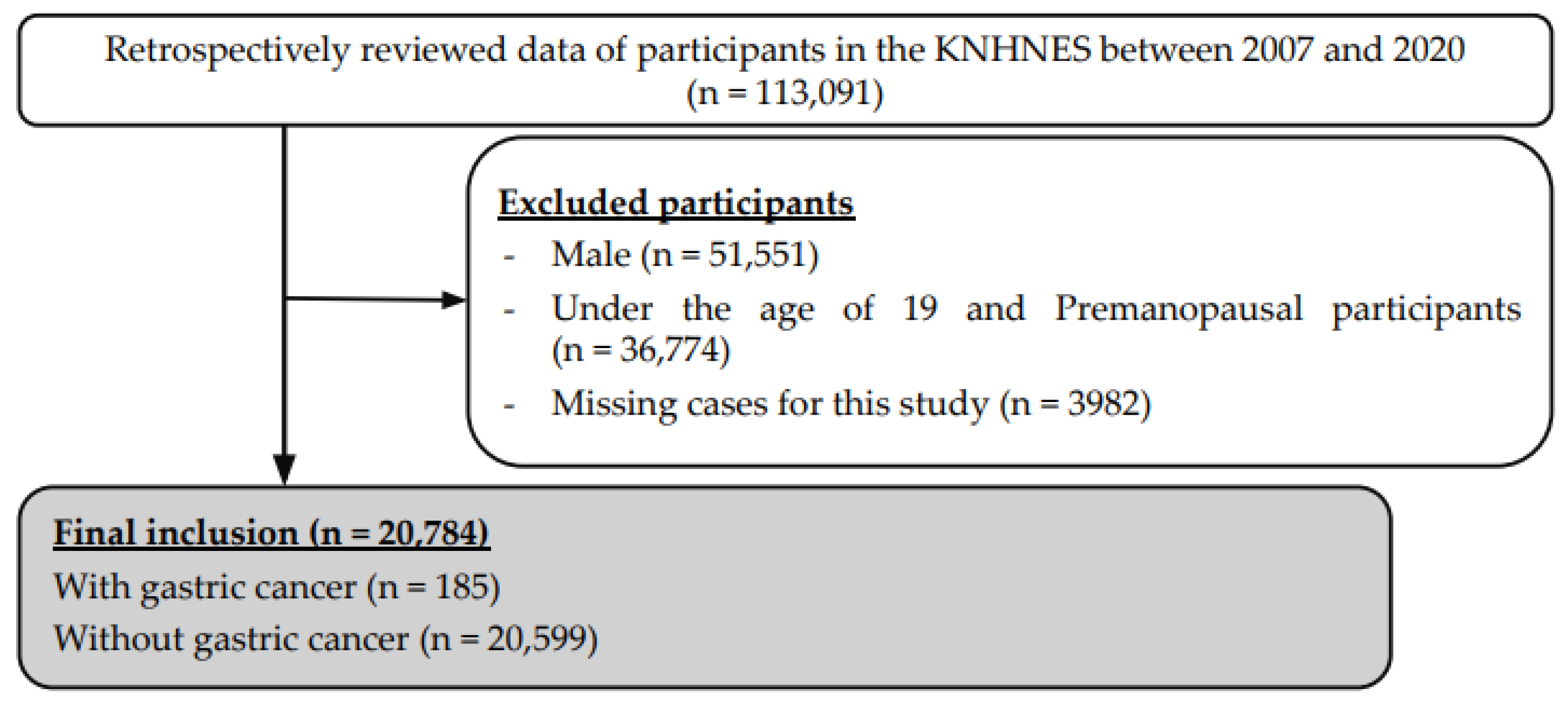

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Menstrual and Reproductive Factors for Gastric Cancer

3.3. Alcohol Consumption, Smoking, and Chronic Diseases for Gastric Cancer

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rahman, M.S.; Cao, J. Estrogen receptors in gastric cancer: Advances and perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 2475–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Won, Y.J.; Lee, J.J.; Jung, K.W.; Kong, H.J.; Im, J.S.; Seo, H.G. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2018. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 53, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Liu, X.; Cheng, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, D. The global, regional and national burden of stomach cancer and its attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2019. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandanos, E.; Lagergren, J. Oestrogen and the enigmatic male predominance of gastric cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 2397–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, N.D.; Chow, W.H.; Gao, Y.T.; Shu, X.O.; Ji, B.T.; Yang, G.; Lubin, J.H.; Li, H.L.; Rothman, N.; Zheng, W.; et al. Menstrual and reproductive factors and gastric cancer risk in a large prospective study of women. Gut 2007, 56, 1671–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frise, S.; Kreiger, N.; Gallinger, S.; Tomlinson, G.; Cotterchio, M. Menstrual and reproductive risk factors and risk for gastric adenocarcinoma in women: Findings from the canadian national enhanced cancer surveillance system. Ann. Epidemiol. 2006, 16, 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.J.; Kuo, F.C.; Hu, H.M.; Chen, C.Y.; Huang, Y.B.; Cheng, K.H.; Yokoyama, K.K.; Wu, D.C.; Hsieh, S.; Kuo, C.H. 17β-Estradiol inhibition of IL-6-Src and Cas and paxillin pathway suppresses human mesenchymal stem cells-mediated gastric cancer cell motility. Transl. Res. 2014, 164, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylander-Koski, O.; Kiviluoto, T.; Puolakkainen, P.; Kivilaakso, E.; Mustonen, H. The effect of nitric oxide, growth factors, and estrogen on gastric cell migration. J. Surg. Res. 2007, 143, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Tamakoshi, A.; Ohno, Y.; Mizoue, T.; Yoshimura, T. Menstrual and reproductive factors and the mortality risk of gastric cancer in Japanese menopausal females. Cancer Causes Control 2003, 14, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.; Kim, Y.; Kweon, S.; Kim, S.; Yun, S.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, Y.; Park, O.; Jeong, E.K. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 20th anniversary: Accomplishments and future directions. Epidemiol. Health 2021, 43, e2021025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sica, V.; Nola, E.; Contieri, E.; Bova, R.; Masucci, M.T.; Medici, N.; Petrillo, A.; Weisz, A.; Molinari, A.M.; Puca, G.A. Estradiol and progesterone receptors in malignant gastrointestinal tumors. Cancer Res. 1984, 44, 4670–4674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kojima, O.; Takahashi, T.; Kawakami, S.; Uehara, Y.; Matsui, M. Localization of estrogen receptors in gastric cancer using immunohistochemical staining of monoclonal antibody. Cancer 1991, 67, 2401–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Min, B.H.; Lee, J.; An, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Sohn, T.S.; Bae, J.M.; Kim, J.J.; Kang, W.K.; Kim, S.; et al. Protective Effects of Female Reproductive Factors on Lauren Intestinal-Type Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Yonsei Med. J. 2018, 59, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.C.; Leung, C.Y.; Huang, H.L. Association of hormone replacement therapy with risk of gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duell, E.J.; Travier, N.; Lujan-Barroso, L.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Palli, D.; Krogh, V.; Mattiello, A.; Tumino, R.; Sacerdote, C.; et al. Menstrual and reproductive factors, exogenous hormone use, and gastric cancer risk in a cohort of women from the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 172, 1384–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, S.; Nakajima, T.; Kobayashi, O.; Yamazaki, T.; Kikuichi, M.; Mori, K.; Oura, S.; Watanabe, H.; Nagawa, H.; Otani, R.; et al. Effect of age on the relationship between gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori. Tokyo Research Group of Prevention for Gastric Cancer. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 2000, 91, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, S. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Gastric. Cancer 2002, 5, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosawa, M.; Kikuchi, S.; Inaba, Y.; Ishibashi, T.; Kobayashi, F. Helicobacter pylori infection among Japanese children. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000, 15, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machlowska, J.; Baj, J.; Sitarz, M.; Maciejewski, R.; Sitarz, R. Gastric Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Genomic Characteristics and Treatment Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duell, E.J.; Travier, N.; Lujan-Barroso, L.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Morois, S.; Palli, D.; Krogh, V.; Panico, S.; Tumino, R.; et al. Alcohol consumption and gastric cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1266–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moy, K.A.; Fan, Y.; Wang, R.; Gao, Y.T.; Yu, M.C.; Yuan, J.M. Alcohol and tobacco use in relation to gastric cancer: A prospective study of men in Shanghai, China. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2010, 19, 2287–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.A.; Choi, B.Y.; Song, K.S.; Park, C.H.; Eun, C.S.; Han, D.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, H.J. Prediagnostic Smoking and Alcohol Drinking and Gastric Cancer Survival: A Korean Prospective Cohort Study. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 73, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gervaso, L.; Dave, H.; Khorana, A.A. Venous and Arterial Thromboembolism in Patients With Cancer: JACC: CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol. 2021, 3, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, T.; Ji, W. Risk Factors for Gastric Cancer-Associated Thrombotic Diseases in a Han Chinese Population. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5544188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ageno, W.; Barni, S.; Di Nisio, M.; Falanga, A.; Imberti, D.; Labianca, R.F.; Mantovani, L. Treatment of venous thromboembolism with tinzaparin in oncological patients. Minerva Med. 2019, 110, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fioretti, A.M.; Leopizzi, T.; Puzzovivo, A.; Giotta, F.; Lorusso, V.; Luzzi, G.; Oliva, S. Cancer-Associated Thrombosis: Not All Low-Molecular-Weight Heparins Are the Same, Focus on Tinzaparin, A Narrative Review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2022, 2022, 2582923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Without Gastric Cancer (n) | With Gastric Cancer (n) | Gastric Cancer (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 680 | 4 | 0.58 |

| 2008 | 1305 | 7 | 0.53 |

| 2009 | 1641 | 14 | 0.85 |

| 2010 | 1632 | 13 | 0.79 |

| 2011 | 1705 | 11 | 0.64 |

| 2012 | 1622 | 15 | 0.92 |

| 2013 | 1419 | 17 | 1.18 |

| 2014 | 1416 | 20 | 1.39 |

| 2015 | 1439 | 16 | 1.10 |

| 2016 | 1587 | 11 | 0.69 |

| 2017 | 1649 | 18 | 1.08 |

| 2018 | 1603 | 12 | 0.74 |

| 2019 | 1547 | 16 | 1.02 |

| 2020 | 1354 | 11 | 0.81 |

| Total | 20,599 | 185 | 0.89 |

| Variables | With Gastric Cancer | Without Gastric Cancer | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) or (M ± SD) | n (%) or (M ± SD) | χ2 or t-Test | p-Value | |

| Age (M ± SD) | 68.58 ± 9.53 | 64.14 ± 9.15 | −6.57 | <0.001 |

| Menstrual and reproductive history | ||||

| Use of the oral contraceptives (n, %) | 45 (24.32) | 4543 (22.05) | 0.55 | 0.459 |

| Age at menarche (M ± SD) | 15.89 ± 2.11 | 14.48 ± 2.02 | −2.74 | 0.006 |

| Age at menopause (M ± SD) | 48.09 ± 5.59 | 49.00 ± 5.09 | 2.41 | 0.016 |

| Age at the first childbirth (M ± SD) | 22.96 ± 3.33 | 23.85 ± 3.59 | 3.31 | <0.001 |

| Age at the last childbirth (M ± SD) | 29.83 ± 4.31 | 29.70 ± 4.49 | −0.36 | 0.718 |

| Frequency of pregnancy (M ± SD) | 4.90 ± 2.35 | 4.66 ± 2.27 | −1.43 | 0.154 |

| Breast feeding experience (n, %) | 149 (94.90) | 15,176 (90.27) | 3.82 | 0.051 |

| Alcohol consumption and smoking history | ||||

| Experience of alcohol consumption (n, %) | 111 (60.00) | 14,422 (70.01) | 8.74 | 0.003 |

| Experience of smoking (n, %) | 18 (9.73) | 1548 (7.52) | 1.28 | 0.257 |

| Period of smoking (M ± SD) | 23.44 ± 89.86 | 16.90 ± 78.63 | −1.13 | 0.261 |

| Chronic disease history | ||||

| Hypertension (n, %) | 78 (42.16) | 8345 (40.51) | 0.21 | 0.649 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 28 (15.14) | 2938 (14.26) | 0.11 | 0.736 |

| Dyslipidemia (n, %) | 27 (14.59) | 5657 (27.46) | 15.28 | <0.001 |

| Stroke (n, %) | 7 (3.78) | 694 (3.37) | 0.10 | 0.756 |

| Myocardial infarction (n, %) | 6 (3.24) | 235 (1.14) | 7.07 | 0.008 |

| Angina pectoris (n, %) | 12 (6.49) | 681 (3.31) | 5.75 | 0.016 |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Menstrual and reproductive history | ||||

| Age at menarche | 1.10 (1.03−1.18) | 0.006 | 1.08 (1.00−1.06) | 0.035 |

| Age at menopause | 0.97 (0.94−0.99) | 0.016 | 0.97 (0.95−1.00) | 0.030 |

| Age at the first childbirth | 0.93 (0.89−0.97) | 0.001 | 0.94 (0.90−0.98) | 0.007 |

| Alcohol consumption and smoking history | ||||

| Experience of alcohol consumption | 0.64 (0.48−0.86) | 0.003 | 0.68 (0.50−0.91) | 0.003 |

| Chronic disease history | ||||

| Dyslipidemia | 0.45 (0.30−0.68) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.59−1.36) | 0.473 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 2.90 (1.27−6.62) | 0.011 | 2.43 (1.05−5.62) | 0.026 |

| Angina pectoris | 2.03 (1.12−3.66) | 0.019 | 1.76 (0.96−3.21) | 0.058 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, H.; Park, J.Y.; Song, J.M.; Yoon, Y.; Kim, Y.-W. Menstrual and Reproductive Factors for Gastric Cancer in Postmenopausal Women: The 2007–2020 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114468

Song H, Park JY, Song JM, Yoon Y, Kim Y-W. Menstrual and Reproductive Factors for Gastric Cancer in Postmenopausal Women: The 2007–2020 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114468

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Heekyoung, Jung Yoon Park, Ju Myung Song, Youngjae Yoon, and Yong-Wook Kim. 2022. "Menstrual and Reproductive Factors for Gastric Cancer in Postmenopausal Women: The 2007–2020 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114468

APA StyleSong, H., Park, J. Y., Song, J. M., Yoon, Y., & Kim, Y.-W. (2022). Menstrual and Reproductive Factors for Gastric Cancer in Postmenopausal Women: The 2007–2020 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114468