Trauma-Informed Design of Supported Housing: A Scoping Review through the Lens of Neuroscience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Trauma, Homelessness and Domestic Violence

2.2. Trauma-Informed Design and Supported Housing

- Reduce or remove known adverse stimuli;

- Reduce or remove environmental stressors;

- Engage the individual actively in a dynamic, multi-sensory environment;

- Provide ways for the individual to exhibit their self-reliance;

- Provide and promote connectedness to the natural world;

- Separate the individual from others who may be in distress;

- Reinforce the individual’s sense of personal identity; and

- Promote the opportunity for choice while balancing program needs and the safety/comfort of the majority.

2.3. Evidence-Based Design and Neuroscience for Architecture

- What is the current evidence on the relationship between the design of the built environment and trauma in the context of supported and how does this correlate with established principles of trauma-informed design?

- What insights can neuroscience offer in extending or questioning our understanding of this evidence and what are the implications for future research?

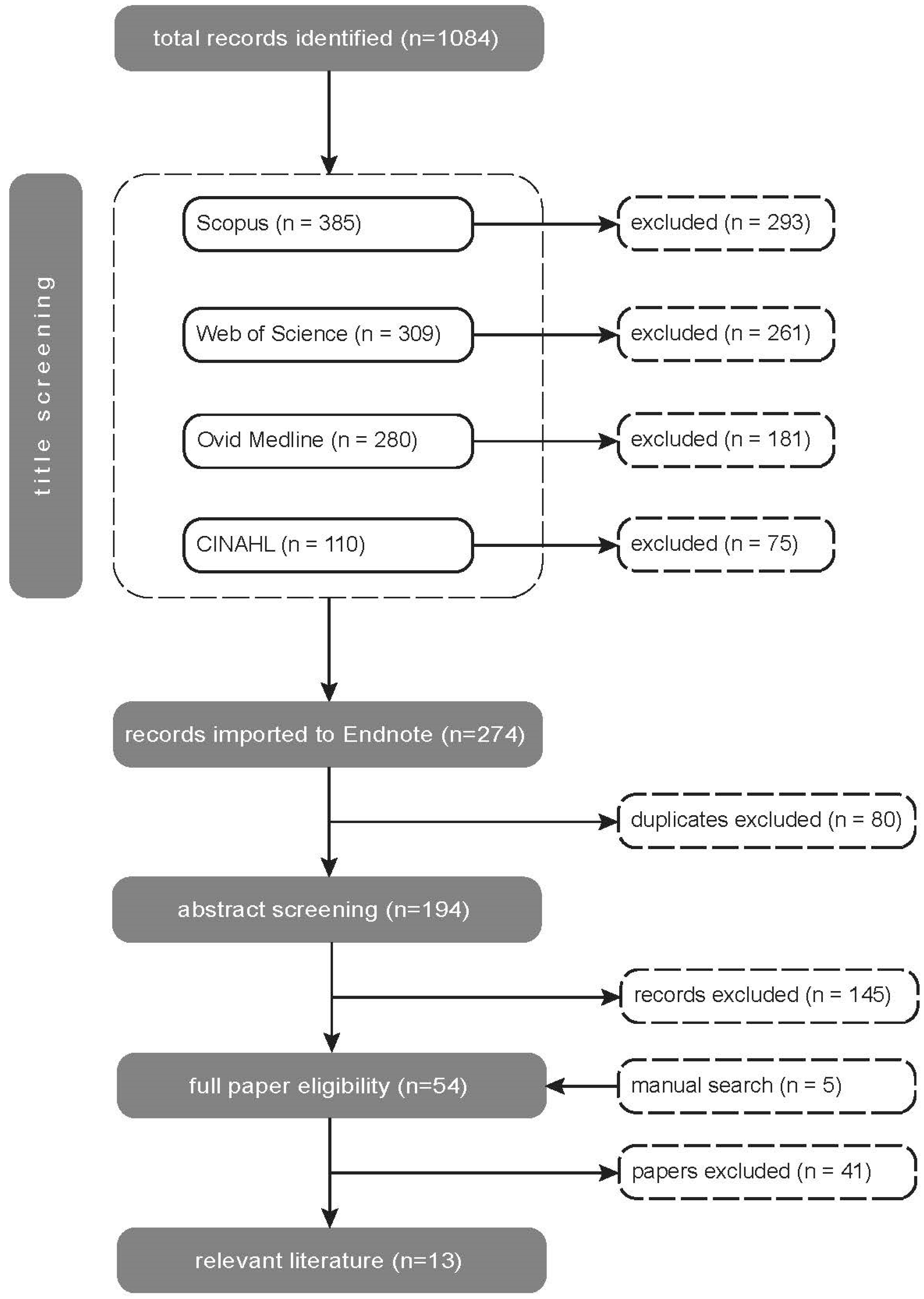

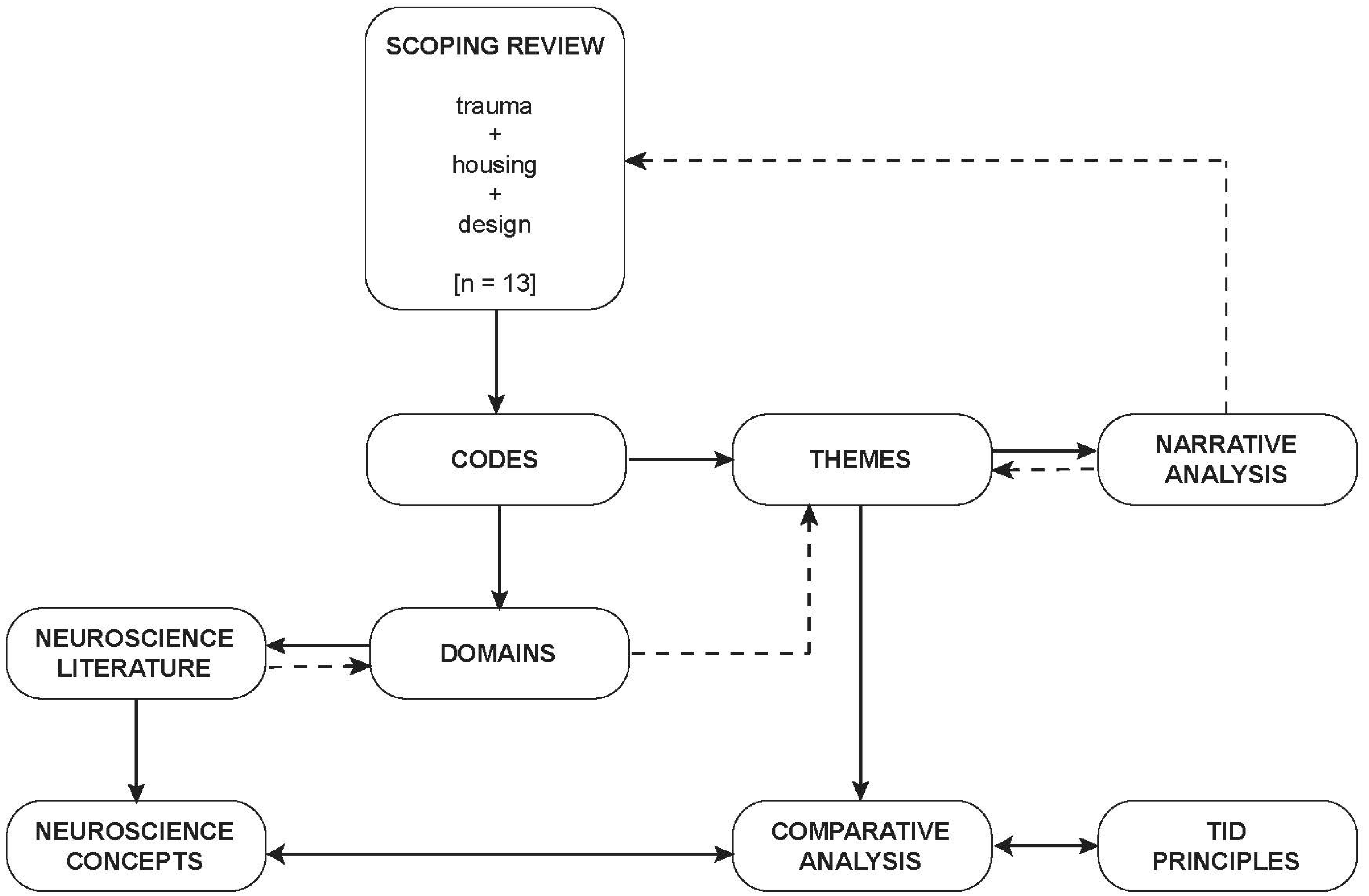

3. Methods

- Directly related to the experience of trauma including both domestic violence and homelessness as well as trauma-related disorders such as PTSD;

- Related to housing context including temporary, transitional and permanent housing;

- Related to the design of the built environment;

- Qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods studies with clearly identified methodology; and

- Peer reviewed journal papers.

- Not explicitly related to experience of trauma including developmental disorders, psychiatric disorders, acquired brain injuries, depression and anxiety disorders, or the experience of staff rather than residents;

- Institutional settings such as care homes, respite and places of incarceration, hotels and other travel accommodation, and any other non-residential setting such as workplaces, educational, recreational or other public buildings or spaces or healthcare environments;

- Not directly related to the design of the built environment;

- Literature reviews, position papers, or any research where research methods were not clearly stated, or papers that repeated/extracted findings from other included studies; and

- Book chapters, conference papers, grey literature or non-peer reviewed papers.

4. Results

4.1. Safety and Security

4.1.1. The Neuroscience of Safety and Security

4.1.2. Safety and Security and Design of the Built Environment in the Reviewed Literature

4.1.3. Safety and Security, Neuroscience and Trauma-Informed Design

4.2. Control

4.2.1. The Neuroscience of Control

4.2.2. Control and Design of the Built Environment in the Reviewed Literature

4.2.3. Control, Neuroscience and Trauma-Informed Design

4.3. Enriched Environments

4.3.1. The Neuroscience of Enriched Environments

4.3.2. Enriched Environments and Design of the Built Environment in the Reviewed Literature

4.3.3. Enriched Environments, Neuroscience and Trauma-Informed Design

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hopper, E.K.; Bassuk, E.L.; Oliver, J. Shelter from the Storm: Trauma-Informed Care in Homelessness Services Settings. Open Health Serv. Policy J. 2010, 3, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Bromet, E.J.; Cardoso, G.; Degenhardt, L.; De Girolamo, G.; Dinolova, R.V.; Ferry, F.; et al. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2017, 8, 1353383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrich, N.; Hodder, T.; Teesson, M. Lifetime Prevalence of Trauma among Homeless People in Sydney. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2000, 34, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitbeck, L.B.; Armenta, B.E.; Gentzler, K.C. Homelessness-Related Traumatic Events and PTSD Among Women Experiencing Episodes of Homelessness in Three U.S. Cities. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, M.; Dalton, L.; Maxwell, H.; Cleary, M. Women and homelessness, a complex multidimensional issue: Findings from a scoping review. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2019, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhall-Melnik, J.; Dunn, J.R.; Svenson, S.; Patterson, C.; Matheson, F.I. Men’s experiences of early life trauma and pathways into long-term homelessness. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 80, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, E.B.; Garvert, D.W.; Macia, K.S.; Ruzek, J.I.; Burling, T.A. Traumatic Stressor Exposure and Post-Traumatic Symptoms in Homeless Veterans. Mil. Med. 2013, 178, 970–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Taylor, K.M.; Sharpe, L. Trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Homeless Adults in Sydney. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2008, 42, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.; Saxe, L.; Harvey, M. Homelessness as psychological trauma: Broadening perspectives. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagdon, S.; Armour, C.; Stringer, M. Adult experience of mental health outcomes as a result of intimate partner violence victimisation: A systematic review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2014, 5, 24794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloitre, M.; Hyland, P.; Bisson, J.I.; Brewin, C.R.; Roberts, N.P.; Karatzias, T.; Shevlin, M. ICD-11 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the United States: A Population-Based Study. J. Trauma. Stress 2019, 32, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollo, C.; Donofrio, A. Trauma-informed design for permanent supportive housing: Four case studies from Seattle and Denver. Hous. Soc. 2021, 49, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollings, K.A.; Bollo, C.S. Permanent supportive housing design characteristics associated with the mental health of formerly homeless adults in the U.S. and Canada: An integrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pable, J.; Ellis, A. Trauma-informed Design: Definitions and Strategies for Architectural Implementation; Design Resources for Homelessness: Tallahassee, FL, USA. Available online: http://designresourcesforhomelessness.org/about-us-1/ (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Jewkes, Y.; Jordan, M.; Wright, S.; Bendelow, G. Designing ‘Healthy’ Prisons for Women: Incorporating Trauma-Informed Care and Practice (TICP) into Prison Planning and Design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, R.E. Trauma-informed care in residential treatment. Resid. Treat. Child. Youth 2014, 31, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trauma-Informed Design Society. Available online: https://traumainformeddesign.org/about-tid/ (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Kopec, D.; Harte, L. Design as the missing variable in trauma-informed schools. In Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students: A Guide for School-Based Professionals, 2nd ed.; Rossen, E., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 343–358. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, K.; Noll, J.G.; Henry, K.A.; Suglia, S.F.; Sarwer, D.B. Trauma-informed neighborhoods: Making the built environment trauma-informed. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesinger, J.G.; Topor, A.; Bøe, T.D.; Larsen, I.B. Studies regarding supported housing and the built environment for people with mental health problems: A mixed-methods literature review. Health Place 2019, 57, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, T. Built community: Architecture, community, and participation in a permanent supportive housing project. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2018, 27, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLane, Y.; Pable, J. Architectural Design Characteristics, Uses, and Perceptions of Community Spaces in Permanent Supportive Housing. J. Inter. Des. 2020, 45, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, P.; Krotofil, J.; Killaspy, H. What Works? Toward a New Classification System for Mental Health Supported Accommodation Services: The Simple Taxonomy for Supported Accommodation (STAX-SA). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieder, M.A.; Chanmugam, A. Applying environmental psychology in the design of domestic violence shelters. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2013, 22, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Watkins, N. Therapeutic Environments. Available online: https://www.wbdg.org/resources/therapeutic-environments (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Donnelly, S. Design Guide for Refuge Accommodation for Women and Children; University of Technology Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2020; pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Washington State Coalition against Domestic Violence. Building Dignity: Design Strategies for Domestic Violence Shelter. Available online: https://buildingdignity.wscadv.org/ (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Ulrich, R.S.; Berry, L.L.; Quan, X.; Parish, J.T. A conceptual framework for the domain of evidence-based design. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2011, 4, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Myron, R.; Stansfeld, S.; Candy, B. A systematic review of the evidence on the effect of the built and physical environment on mental health. J. Public Ment. Health 2007, 6, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, C.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Galea, S. Are Neighborhood Characteristics Associated with Depressive Symptoms? A Critical Review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D. Blues from the Neighborhood? Neighborhood Characteristics and Depression. Epidemiol. Rev. 2008, 30, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Palmer, S.; Gallacher, J.; Marsden, T.; Fone, D. A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environ. Int. 2016, 96, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, S.; Tobin, D.; Avison, W.; Gilliland, J. Mental health benefits of interactions with nature in children and teenagers: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderton, A.; Villanueva, K.; O’Connor, M.; Boulangé, C.; Badland, H. Reducing Inequities in Early Childhood Mental Health: How Might the Neighborhood Built Environment Help Close the Gap? A Systematic Search and Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, M.A.; Golembiewski, J.A.; Moustafa, A.A. Mental health and urban design—Zoning in on PTSD. Curr. Psychol. Res. Rev. 2020, 39, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckney, P.; Bentley, R. The urban public realm and adolescent mental health and wellbeing: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 284, 114242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Dennis, S., Jr.; Mohammed, H. Mental Health Outcome Measures in Environmental Design Research: A Critical Review. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2021, 14, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollander, J.; Foster, V. Brain responses to architecture and planning: A preliminary neuro-assessment of the pedestrian experience in Boston, Massachusetts. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2016, 59, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, A.; Hollander, J.B. Cognitive Architecture: Designing for How We Respond to the Built Environment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–193. [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, A.; Vartanian, O.; Chatterjee, A. Buildings, beauty, and the brain: A neuroscience of architectural experience. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017, 29, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszewska-Guizzo, A.; Escoffier, N.; Chan, J.; Yok, T.P. Window view and the brain: Effects of floor level and green cover on the alpha and beta rhythms in a passive exposure eeg experiment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golembiewski, J.A. The Designed Environment and How it Affects Brain Morphology and Mental Health. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2016, 9, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, B.M.; Lundman, B.; Graneheim, U.H. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 108, 103632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lindgren, B.M.; Lundman, B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 56, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A. “Homed” in Arizona: The architecture of emergency shelters. Urban Geogr. 2005, 26, 536–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, K.; Collins, A.B.; Burgess, H.; Von Bischoffshausen, O.; Marziali, M.; Salters, K.A.; Hogg, R.S.; Parashar, S. Understanding the pervasiveness of trauma within a housing facility for people living with HIV. Hous. Stud. 2020, 35, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygum, V.L.; Poulsen, D.V.; Djernis, D.; Djernis, H.G.; Sidenius, U.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Post-Occupancy Evaluation of a Crisis Shelter Garden and Application of Findings Through the Use of a Participatory Design Process. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2019, 12, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, H.; Walsh, C.A. Shelter design and service delivery for women who become homeless after age 50. Can. J. Urban Res. 2014, 23, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nuamah, J.; Rodriguez-Paras, C.; Sasangohar, F. Veteran-Centered Investigation of Architectural and Space Design Considerations for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Health Environ. Res. Des. J. (HERD) 2021, 14, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pable, J. The Homeless Shelter Family Experience: Examining the Influence of Physical Living Conditions on Perceptions of Internal Control, Crowding, Privacy, and Related Issues. J. Inter. Des. 2012, 37, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.; Maas, J.; Hovinga, D.; Van Den Bogerd, N.; Schuengel, C. Experiencing nature to satisfy basic psychological needs in parenting: A quasi-experiment in family shelters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.; Hovinga, D.; Maas, J.; Schuengel, C. Exposure to a natural environment to improve parental wellbeing in parents in a homeless shelter: A multiple baseline single case intervention study. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refuerzo, B.J.; Verderber, S. Effects of Personal Status and Patterns of Use on Residential Satisfaction in Shelters for Victims of Domestic Violence. Environ. Behav. 1989, 21, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refuerzo, B.J.; Verderber, S. Dimensions of person-environment relationships in shelters for victims of domestic violence. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 1990, 7, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Marcus, C. House as a Mirror of Self: Exploring the Deeper Meaning of Home; Conari Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B.S. Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress. Chronic Stress 2017, 1, 247054701769232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; McEwen, B.S.; Friston, K. Uncertainty and stress: Why it causes diseases and how it is mastered by the brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 156, 164–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: Central role of the brain. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 8, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNally, G.P.; Westbrook, R.F. Predicting danger: The nature, consequences, and neural mechanisms of predictive fear learning. Learn. Mem. 2006, 13, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeDoux, J. Rethinking the Emotional Brain. Neuron 2012, 73, 653–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeDoux, J. The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2003, 23, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asok, A.; Kandel, E.R.; Rayman, J.B. The neurobiology of fear generalization. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, Á.; Fullana, M.À.; Soriano-Mas, C.; Andero, R. Lost in translation: How to upgrade fear memory research. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 2122–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanbakht, A. A theory of everything: Overlapping neurobiological mechanisms of psychotherapies of fear and anxiety related disorders. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maren, S. Seeking a Spotless Mind: Extinction, Deconsolidation, and Erasure of Fear Memory. Neuron 2011, 70, 830–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangha, S.; Diehl, M.M.; Bergstrom, H.C.; Drew, M.R. Know safety, no fear. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 108, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, E.; Monje, F.J.; Hirsch, J.; Pollak, D.D. Learning not to Fear: Neural Correlates of Learned Safety. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krypotos, A.M.; Effting, M.; Kindt, M.; Beckers, T. Avoidance learning: A review of theoretical models and recent developments. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treanor, M.; Barry, T.J. Treatment of avoidance behavior as an adjunct to exposure therapy: Insights from modern learning theory. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 96, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrenz, F.; Woud, M.L.; Elsenbruch, S.; Icenhour, A. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly—Chances, Challenges, and Clinical Implications of Avoidance Research in Psychosomatic Medicine. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 841734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanovic, T.; Kazama, A.; Bachevalier, J.; Davis, M. Impaired safety signal learning may be a biomarker of PTSD. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, V.; Wang, K.S.; Bhanji, J.; Delgado, M.R. A reward-based framework of perceived control. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huys, Q.J.M.; Dayan, P. A Bayesian formulation of behavioral control. Cognition 2009, 113, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryce, C.R.; Azzinnari, D.; Spinelli, S.; Seifritz, E.; Tegethoff, M.; Meinlschmidt, G. Helplessness: A systematic translational review of theory and evidence for its relevance to understanding and treating depression. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 132, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, S.; Kristin, H. The nursing home as a home: A field study of residents’ daily life in the common living rooms. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Horst, H. Living in a reception centre: The search for home in an institutional setting. Hous. Theory Soc. 2004, 21, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, P.L.; Chiu, M.Y.-L. An ecological study of families in transitional housing—‘housed but not homed’. Hous. Stud. 2016, 31, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overmier, J.B.; Seligman, M.E. Effects of inescapable shock upon subsequent escape and avoidance responding. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1967, 63, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroto, D.S.; Seligman, M.E. Generality of learned helplessness in man. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 31, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R. Learned helplessness, depression and the perception of reinforcement. Behav. Res. Ther. 1976, 14, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.C.; Seligman, M.E. Reversal of performance deficits and perceptual deficits in learned helplessness and depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1976, 85, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, D.C.; Fencil-Morse, E.; Seligman, M.E. Learned helplessness, depression, and the attribution of failure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1976, 33, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S.F.; Seligman, M.E.P. Learned helplessness at fifty: Insights from neuroscience. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 123, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgaz, C.; Estevez, A.; Matute, H. Pathological gamblers are more vulnerable to the illusion of control in a standard associative learning task. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.; Averbeck, B.; Payer, D.; Sescousse, G.; Winstanley, C.A.; Xue, G. Pathological choice: The neuroscience of gambling and gambling addiction. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 17617–17623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigoli, F.; Pezzulo, G.; Dolan, R.J. Prospective and Pavlovian mechanisms in aversive behaviour. Cognition 2016, 146, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huys, Q.J.M.; Daw, N.D.; Dayan, P. Depression: A Decision-Theoretic Analysis. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 38, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queen, N.J.; Hassan, Q.N., II; Cao, L. Improvements to Healthspan Through Environmental Enrichment and Lifestyle Interventions: Where Are We Now? Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubert, C.; Hannan, A.J. Environmental enrichment as an experience-dependent modulator of social plasticity and cognition. Brain Res. 2019, 1717, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Carvajal, M.; Sequeira-Cordero, A.; Brenes, J.C. The environmental enrichment model revisited: A translatable paradigm to study the stress of our modern lifestyle. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022, 55, 2359–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempermann, G. Environmental enrichment, new neurons and the neurobiology of individuality. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, H.; Olivier, B.; Oosting, R.S. From non-pharmacological treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder to novel therapeutic targets. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 732, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofton, E.J.; Zhang, Y.; Green, T.A. Inoculation stress hypothesis of environmental enrichment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 49, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smail, M.A.; Smith, B.L.; Nawreen, N.; Herman, J.P. Differential impact of stress and environmental enrichment on corticolimbic circuits. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2020, 197, 172993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich-Lai, Y.M.; Herman, J.P. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venniro, M.; Zhang, M.; Caprioli, D.; Hoots, J.K.; Golden, S.A.; Heins, C.; Morales, M.; Epstein, D.H.; Shaham, Y. Volitional social interaction prevents drug addiction in rat models. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1520–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward Thompson, C.; Roe, J.; Aspinall, P.; Mitchell, R.; Clow, A.; Miller, D. More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Cline, H.; Turkheimer, E.; Duncan, G.E. Access to green space, physical activity and mental health: A twin study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, R. Does Access to Green Space Impact the Mental Well-being of Children: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 37, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanaken, G.-J.; Danckaerts, M. Impact of Green Space Exposure on Children’s and Adolescents’ Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Mavoa, S.; Zhao, J.; Raphael, D.; Smith, M. The Association between Green Space and Adolescents’ Mental Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Qi, J.; Li, W.; Dong, J.; van den Bosch, C.K. The Contribution to Stress Recovery and Attention Restoration Potential of Exposure to Urban Green Spaces in Low-Density Residential Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, B.; Chen, H.; Li, Z. Exploring the linkage between greenness exposure and depression among Chinese people: Mediating roles of physical activity, stress and social cohesion and moderating role of urbanicity. Health Place 2019, 58, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soto, J.; Lena, M.M.L.; Vázquez, A.C. Psychological restoration and urban nature: Some mental health implications. Salud Ment. 2014, 37, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Berto, R. The Role of Nature in Coping with Psycho-Physiological Stress: A Literature Review on Restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautio, N.; Filatova, S.; Lehtiniemi, H.; Miettunen, J. Living environment and its relationship to depressive mood: A systematic review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; Wiley: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Henwood, B.F.; Lahey, J.; Harris, T.; Rhoades, H.; Wenzel, S.L. Understanding Risk Environments in Permanent Supportive Housing for Formerly Homeless Adults. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 2011–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme Area | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Trauma | “trauma-informed care” OR “trauma-informed practices” OR “trauma-informed design” OR “post-traumatic stress” OR “PTSD” OR “domestic violence” OR “partner violence” or “family violence” OR “interpersonal trauma” OR “traumatic violence” OR “child abuse” OR “childhood adversity” OR homeless * OR “mental health” |

| Design | “architecture and design” OR “architectural design” OR “physical design” OR “spatial design” OR “space design” OR “built environment design” OR “housing design” or “shelter design” or “refuge design” OR “interior design” OR “landscape design” OR “design features” OR “design elements” OR “built environment features” OR “built environment properties” OR “built environment characteristics” OR “environmental characteristics” OR “physical environment” OR “housing environment” OR “place attributes” OR “person-environment relationships” OR “trauma-informed design” |

| Housing | “supportive housing” OR “permanent housing” OR “temporary housing” OR “transitional housing” OR “crisis shelter” or “emergency shelter” OR “temporary shelter” OR “transitional shelter” OR shelter OR refuge OR hous* OR home OR residen* |

| Reference | Country | Key Focus | Study Design | Demographic | Housing Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bollo & Donofrio, 2021 [12] | USA | Application of Trauma-informed Design (TID) principles in the common areas of permanent supportive housing. | Qualitative case study: walking interviews with staff, environmental observations, and analysis of floor plans and meeting minutes of trauma-informed design renovation committee. No interviews with residents, but ‘evidence of use’ analysed through environmental observations and meeting minutes included resident representation on committee. | Formerly homeless people | Comparison of four ‘primary’ (TID) case study buildings and four ‘negative’ case study buildings. Primary study buildings comprise recently renovated [n = 3] and purpose-built [n = 1] permanent supportive housing (ranging from 46-84 units) with on-site support services. |

| Datta, 2005 [46] | USA | The relationship between feelings of ‘home’ and ‘homelessness’ and the architecture of emergency homeless shelters. | Qualitative case study: in-depth interviews with residents [n = 10] and environmental observations of common spaces (external, offices, childcare). | Homeless families | Single study site: emergency shelter in converted ‘run-down’ motel (30 families) with on-site support services. |

| Huffman, 2018 [21] | USA | Role of community space in supporting wellbeing in permanent supportive housing. | Qualitative case study: immersion in context (participation and engagement in meetings and activities) and in-depth interviews [n = 26] | Formerly homeless | Single study site: purpose-built permanent supportive housing (100 residents) with on-site support services |

| Koehn et al. 2020 [47] | Canada | The impact of trauma histories on the experiences of daily living and health outcomes for people living with HIV in supportivehousing environments. | Qualitative study: semi-structured interviews (24 participants) | Adults living with HIV who have experienced or are at-risk of homelessness. | Single study site: purpose-built permanent supportive housing (large facility) with on-site support services |

| Lygum et al., 2019 [48] | Denmark | Testing of guidelines for gardens to support health and wellbeing in crisis shelters for women and children exposed to domestic violence. | Qualitative case study: post-occupancy evaluation including analysis of landscape design, environment observation (physical traces), walking semi-structured interviews with staff [n = 12] and residents [n = 3] and participatory design/education program with staff. | Victims/ survivors of domestic violence | Single study site: crisis shelter in newly renovated historic building including evidence-based garden design (17 families) with on-site support services. |

| McLane & Pable, 2020 [22] | UK and USA | The design of interior communal spaces in supportive housing to aid in recovery from trauma. | Mixed methods case studies: exploratory questionnaires [n = 28], open-ended interviews [n = 18] with both residents and staff, space syntax analysis, and environmental observation via photography. | People escaping homelessness or at-risk of homelessness | Two study sites: transitional supportive housing in modified existing buildings with mix of shared and private rooms. |

| McLeod & Walsh, 2014 [49] | Canada | The experiences of women who become homeless after age 50 and the implications for shelter site, situation and service delivery. | Qualitative study: in-depth interviews [n = 8]. | Older homeless women | Multiple temporary shelters with on-site support services. |

| Nuamah et al., 2021 [50] | USA | Identifying architectural and space design considerations and guidelines for veterans diagnosed with PTSD. | Qualitative study: in-depth semi-structured interviews [n = 17]. | Veterans diagnosed with PTSD | No specific site: participant reflections on ‘general buildings’ including ‘both public and private spaces’ and ‘ideal living area’. |

| Pable, 2012 [51] | USA | Relationship between the design of homeless shelter bedrooms and perceptions of internal control, crowding and privacy. | Qualitative case study: comparison of design intervention in private dormitory bedroom (pre and post occupation) [n = 1] and continuous occupation of an unaltered private dormitory bedroom [n = 1] employing self-directed photography and in-depth interviews with occupants [n = 2], quantitative self-report questionnaire measurement [n = 2], photographic observation by researcher, and interviews with case-study managers [n = 2]. | Single mothers with children escaping homelessness | Single study site: transitional homeless shelter (20 bedrooms). |

| Peters et al. 2020 [52] | Netherlands | Impact of natural environment on wellbeing of parents in homeless shelters. | Quantitative study: comparative questionnaire of parental need satisfaction and need frustration and connectedness with nature during personalized ‘nature experience’ intervention and in ‘standard indoor environment’ [n = 160] and staff questionnaire outlining activity and observations. | Parents of children escaping homelessness | Multiple study sites: women’s and/or homeless shelters. |

| Peters et al., 2021 [53] | Netherlands | Impact of personalized exposure to natural environments on wellbeing of parents in homeless shelters. | Quantitative single case experiment: repeated and randomized exposure to indoor environment (baseline phases) and natural environment (intervention phases) for parents residing in shelters, self-report questionnaire on psychological need fulfilment and wellbeing, and affective state (alter report) by researcher. [n = 3] | Parents of children escaping homelessness | Single site: transitional homeless shelter for families. |

| Refuerzo & Verderber, 1989 [54] | USA | Identifying underlying determinants of satisfaction for residents and staff in shelters for victims of domestic violence. | Quantitative study: survey with residents [n = 51] and staff [n = 50]. | Victims/ survivors of domestic violence | Multiple study sites: temporary shelters for women and children [n = 6]. |

| Refuerzo & Verderber, 1990 [55] | USA | Perceptions of environment for residents and staff in domestic violence shelters. | Quantitative study: photo-questionnaire/survey with residents [n = 51] and staff [n = 50]. | Victims/ survivors of domestic violence | Multiple study sites: temporary shelters for women and children [n = 6]. |

| Bollo & Donofrio, 2021 [12] | Datta, 2005 [46] | Huffman, 2018 [21] | Koehn et al. 2020 [47] | Lygum et al., 2019 [48] | McLane & Pable, 2020 [22] | McLeod & Walsh, 2014 [49] | Nuamah et al., 2021 [50] | Pable, 2012 [51] | Peters et al. 2020 [52] | Peters et al. 2021 [53] | Refuerzo & Verderber, 1989 [54] | Refuerzo & Verderber, 1990 [55] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety and Security | ||||||||||||||

| Defensible environments | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||

| Visibility | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||

| Concealment | • | • | • | |||||||||||

| Escape | • | • | ||||||||||||

| Secure boundaries | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||

| Environmental stressors | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||

| Residence | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||

| Neighbourhood | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||

| Control | ||||||||||||||

| Self-reliance | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||

| Territory | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||

| Personal space | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||

| Common space | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||

| Enriched Environments | ||||||||||||||

| Connection to nature | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||

| Environmental diversity | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||

| Image | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||

| Reduce or Remove Adverse Stimuli | Reduce or Remove Environmental Stressors | Engage the Individual Actively in a Dynamic, Multi-Sensory Environment | Provide Ways for the Individual to Exhibit Their Self-Reliance | Provide and Promote Connectedness to the Natural World | Separate the Individual from others who may Be in Distress | Reinforce the Individual’s Sense of Personal Identity | Promote the Opportunity for Choice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety and Security | ||||||||

| Defensible environments | ||||||||

| Environmental stressors | ||||||||

| Control | ||||||||

| Self-reliance | ||||||||

| Territory | ||||||||

| Enriched Environments | ||||||||

| Connection to nature | ||||||||

| Environmental diversity | ||||||||

| Image | ||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Owen, C.; Crane, J. Trauma-Informed Design of Supported Housing: A Scoping Review through the Lens of Neuroscience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114279

Owen C, Crane J. Trauma-Informed Design of Supported Housing: A Scoping Review through the Lens of Neuroscience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114279

Chicago/Turabian StyleOwen, Ceridwen, and James Crane. 2022. "Trauma-Informed Design of Supported Housing: A Scoping Review through the Lens of Neuroscience" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114279

APA StyleOwen, C., & Crane, J. (2022). Trauma-Informed Design of Supported Housing: A Scoping Review through the Lens of Neuroscience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114279