Moderating Effects of Self-Esteem on the Relationship between Communication Anxiety and Academic Performance among Female Health College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Research Instrument

2.2.1. Sociodemographic and General Health Characteristics with COVID-19-Related Information

2.2.2. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

2.2.3. Personal Report of Communication Apprehension (PRCA-24)

2.2.4. Dual-Moderator Focus Group Process

2.2.5. Focus Group Guide

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Qualitative Analysis

4.1. Theme 1. Communication Patterns

4.1.1. Before Pandemic

“Yes, actually, I have been a talkative person since elementary school. I took around 100% in competition at King Saud.”(R1)

“Before COVID, I was so confident. So, I used to depend upon my mental skills before. I got many awards by using my mental skills and ability.”(R4)

“For presentations and things that are the group work, I used to be only for leading everything. I used to be so confident. It’s fine with me, you can count on me, it’s OK. I never prepare it early, as long as I know for the scientific parts—I am pretty good.”(R2)

“I was socially active and was not staying at the house with my family.”(R6)

On the other hand, one participant shared, “I’m not a very communicative person” (R5), and one did not report any difference in communication patterns.

4.1.2. After Pandemic

“It took too long to take part in speech with a lot of people. It was affected at many levels. I’m sorry to speak in Arabic, but it gives me more comfort to use it.”(R1)

“I lose my confidence, so I don’t know how to start [a] new conversation. I feel like, oh, I do this far, I do bad. I lost the basic skills of conversation, maybe.”(R4)

“Now I have to discuss with the leader what I [am] supposed to do for presentations? How long? I never used to do these things before.”(R2)

“I lost myself, but I’m trying to come back to my old habit, so it’s affected me a lot.”(R6)

According to Respondent 5, “After the pandemic, it has helped me to be more aware that we are all in one small world. We should get to know each other better because we are all humans, we like to be in one group, and we like to feel to belong. So now, right now, after the pandemic, I have so many friendships. I even got to communicate with my doctors (teachers).”

Respondent 3 added, “Communication [has] become better.”

4.2. Theme 2. Psychological Impact

4.2.1. Psychological Issues

“Previously, I was stable, [did] not have stress, [did] not have disorganizing thoughts. Right now, everything is changed. I had [a] presentation in the last week that [made] me [so] angry that I was shaking. It’s the first time actually—this is what makes me cry after the presentation. I don’t want to cry, yeah, because it’s difficult for me, the person that [has] a lot of conversations, talks with a lot of people—shaking is not normal for me. This is the first-time presentation after the pandemic.”(R1)

“So, the anxiety level around people, I mean, like, 18 persons and above, I got anxiety.”(R5)

“I’m sensitive now. I face [a stressful] situation; I cry. My teacher suddenly asked me a question—I [was] stuck on one word.”(R4)

“After the pandemic, I used to write [notes] for each thing I have. I’m supposed to say even my comment, even my side thing, or even a good morning doctor. I would like to write down to make sure that I don’t forget anything.”(R2)

“I was crying all the time. I lost a lot of aspects of my personality in this. And this year, I think I lost myself. I didn’t know if I even have doubt with my specialty. Do Iwant to continue to be (…) Is this worth it to continue? This adds depression.”(R6)

4.2.2. Anxiety Triggering Event

4.2.3. Problem Solving

“So, I prefer to just close [my] mouth and just listen.”(R4)

“I wish I can find the solution for my anxiety.”(R5)

“So, it’s like you know this is the issue I have to find a solution for.”(R1)

At the end of the focus group, they were asked if they wanted to add anything. One of the participants added the following:

“I want to mention something about that. I was having a conversation with my colleagues about how they change, and their communications like with the families, with a friend. Most of them, around 10 to 11 (people) in the communication circle—they [are] suffering, [and] they show a significant impact in their patterns of communication, with their family, friends in the university with the doctors (teachers), so perhaps you (professionals) could do something for them. This information could help you in the future, also this seems to spread in all the other students, not only [depending] on us here.”(R1)

5. Discussion

6. Study Limitations and Future Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dwyer, K. iConquer Speech Anxiety: A Workbook to Help You Overcome Your Nervousness & Anxiety about Public Speaking; KLD Book: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, V.P.; McCroskey, J.C. Communication: Apprehension, Avoidance, and Effectiveness; Pearson College Division: Engelwood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hasibuan, S.H.; Manurung, I.D.; Ekayati, R. Investigating Public Speaking Anxiety Factors among EFL. Appl. Res. Engl. 2022, 11, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.T.S.; Regencia, Z.J.G.; Dela Cruz, J.R.C.; Ho, F.D.V.; Rodolfo, M.S.; Ly-Uson, J.; Baja, E.S. Assessing the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, shift to online learning, and social media use on the mental health of college students in the Philippines: A mixed-method study protocol. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentiss, S. Speech Anxiety in the Communication Classroom during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Supporting Student Success. Front. Commun. 2021, 6, 642109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messman, S.J.; Jones-Corley, J. Effects of communication environment, immediacy, and communication apprehension on cognitive and affective learning. Commun. Monogr. 2001, 68, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajitha, K.; Alamelu, C. A study of factors affecting and causing speaking anxiety. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 172, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.H.; Agrawal, S. Do communication barriers in student teams impede creative behavior in the long run?—A time-lagged perspective. Think. Ski. Creat. 2017, 26, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attarabeen, O.F.; Gresham-Dolby, C.; Broedel-Zaugg, K. Pharmacy student stress with transition to online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2021, 13, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R.; Murphy, F.; Hogg, P. The impact of teaching experimental research on-line: Research-informed teaching and COVID-19. Radiography 2021, 27, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.; Mansour, A.E.; Fadda, W.A.; Almisnid, K.; Aldamegh, M.; Al-Nafeesah, A.; Alkhalifah, A.; Al-Wutayd, O. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.; Leon, G.; Patel, D.; Lee, C.; Simanton, E. The Impact of COVID-19 on Academic Performance and Personal Experience Among First-Year Medical Students. Med. Sci. Educ. 2022, 32, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, L.; Mammarella, S.; Salza, A.; Del Vecchio, S.; Ussorio, D.; Casacchia, M.; Roncone, R. Predictors of academic performance during the covid-19 outbreak: Impact of distance education on mental health, social cognition and memory abilities in an Italian university student sample. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B. The Role of Classroom Contexts on Learners’ Grit and Foreign Language Anxiety: Online vs. Traditional Learning Environment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 869186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qanash, S.; Al-Husayni, F.; Alemam, S.; Alqublan, L.; Alwafi, E.; Mufti, H.N.; Qanash, H.; Shabrawishi, M.; Ghabashi, A. Psychological Effects on Health Science Students After Implementation of COVID-19 Quarantine and Distance Learning in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2020, 12, e11767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azmi, F.M.; Khan, H.N.; Azmi, A.M.; Yaswi, A.; Jakovljevic, M. Prevalence of COVID-19 Pandemic, Self-Esteem and Its Effect on Depression Among University Students in Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 836688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Panzeri, A.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Castelnuovo, G.; Mannarini, S. The Anxiety-Buffer Hypothesis in the Time of COVID-19: When Self-Esteem Protects from the Impact of Loneliness and Fear on Anxiety and Depression. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Mccroskey, J.C.; Richmond, V.P.; Daly, J.A.; Falcione, R.L. Studies of the Relationship Between Communication Apprehension and Self-Esteem. Hum. Commun. Res. 1977, 3, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, U.; Awad, S.S.; Mortada, E.M.; Qasem, H.D.; Kayal, G.F. Psychometric evaluation of Arabic version of Self- Esteem, Psychological Well-being and Impact of weight on Quality of life questionnaire (IWQOL-Lite) in female student sample of PNU. Eur. Med. Health Pharm. J. 2015, 8, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofstad, W.; Brunner, L.J. Team-based learning in pharmacy education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2013, 77, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, C.; Mears, M.; Rowan, S.; Dong, F.; Andrews, E. Academic performance and attitudes of dental students impacted by COVID-19. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 86, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolatov, A.K.; Seisembekov, T.Z.; Askarova, A.Z.; Baikanova, R.K.; Smailova, D.S.; Fabbro, E. Online-Learning due to COVID-19 Improved Mental Health Among Medical Students. Med. Sci. Educ. 2020, 31, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Campbell, J.D.; Krueger, J.I.; Vohs, K.D. Does High Self-Esteem Cause Better Performance, Interpersonal Success, Happiness, or Healthier Lifestyles? Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2003, 4, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, M.Z.; Gerard, J.M. Self-esteem and academic achievement: A comparative study of adolescent students in England and the United States. Compare 2011, 41, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCroskey, J.C.; Richmond, V.P. Communication apprehension as a predictor of self-disclosure. Commun. Q. 1977, 25, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafek, M.B.; Ramli, N.H.L.B.; Iksan, H.B.; Harith, N.M.; Abas, A.I.B.C. Gender and Language: Communication Apprehension in Second Language Learning. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 123, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, J.; Marlow, A.; Wathen, J. Communication Apprehension and its Relationship to Gender and College Year. J. Undergrad. Res. Minnesota State Univ. Mankato 2005, 5, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Son, C.; Hegde, S.; Smith, A.; Wang, X.; Sasangohar, F. Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourhis, J.; Allen, M. Meta-analysis of the relationship between communication apprehension and cognitive. Commun. Educ. 1992, 41, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Muhammad, S.; Mahmood, K. Self-Esteem & Academic Performance Among University students. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Charan, J.; Biswas, T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2013, 35, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health. 2007. Available online: http://www.OpenEpi.com (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- McCroskey, J.C. An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- McCroskey‚, J.C.; Beatty‚, M.J.; Kearney‚, P.; Timothy, P.G. The Content Validity of the PRCA-24 as a Measure of Communication Apprehension across Communication Contexts. Commun. Q. 1985, 33, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendli, A. Communication Apprehension Among UAE Students: Implications and Recommendations in Midraj, S.A. In Research in ELT Contexts; TESOL Arabia: Dubai, Arabia, 2007; pp. 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, G.H.; Jackson, I.R.; Visram, A.S. Impacts of face coverings on communication: An indirect impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Audiol. 2021, 60, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mheidly, N.; Fares, M.Y.; Zalzale, H.; Fares, J. Effect of Face Masks on Interpersonal Communication During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 582191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealy, M.K. Communication in the Time of COVID-19: An Examination of Imagined Interactions and Communication Apprehension During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 2021, 41, 158–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colliver, J.A.; Swartz, M.H.; Robbs, R.; Cohen, D. Relationship between clinical competence and interpersonal and communication skills in standardized-patient assessment. Acad. Med. 1999, 74, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zraick, R.I.; Allen, R.M.; Johnson, S.B. The use of standardized patients to teach and test interpersonal and communication skills with students in speech-language pathology. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2003, 8, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, H.; Khor, J.; Mozaka, G.M.; Kayode, B.K.; Mehmood Khan, T. Prevalence of communication apprehension among college and university students and its association with demographic factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2017, 8, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, L.A.; MacIntyre, P.D. Age and sex differences in willingness to communicate, communication apprehension, and self-perceived competence. Commun. Res. Rep. 2004, 21, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, K.K. Communication apprehension and learning style preference: Correlations and implications for teaching. Commun. Educ. 1998, 47, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, D.; Croucher, S.M. Minority groups and communication apprehension: An investigation of Kurdistan. J. Intercult. Commun. 2017, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Lasode, A.O.; Awote, M.F. Challenges Faced by Married University Undergraduate Female Students in Ogun State, Nigeria. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 112, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, Z.; Shokrpour, N.; Valinejad, M.; Hadavi, M. Communication apprehension and level of anxiety in the medical students of Rafsanjan. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 29, 350. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M.; Korayem, A.S.; El-Nayal, M.A. Self-esteem among college students from four Arab countries. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 110, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, L.L.; Orth, U.; Denissen, J.J.A.; Kühnel, A. Age differences in instability, contingency, and level of self-esteem across the life span. J. Res. Pers. 2011, 45, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.; Robins, R.W.; Roberts, B.W. Low Self-Esteem Prospectively Predicts Depression in Adolescence and Young Adulthood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gammon, J. Analysis of the stressful effects of hospitalisation and source isolation on coping and psychological constructs. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 1998, 4, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purssell, E.; Gould, D.; Chudleigh, J. Impact of isolation on hospitalised patients who are infectious: Systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e030371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puddey, I.B.; Mercer, A. Predicting academic outcomes in an Australian graduate entry medical programme. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadalla, S.; Davies, E.B.; Glazebrook, C. A longitudinal cohort study to explore the relationship between depression, anxiety and academic performance among Emirati university students. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, B.D.; Baldwin, T.; Ryan, K.C. Communication apprehension: A barrier to learning, leadership, and multicultural appreciation. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2013, 12, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappe, R.; Van Der Flier, H. Predicting academic success in higher education: What’s more important than being smart? Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2012, 27, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allah, A.A.; Algethami, N.E.; Algethami, R.A.; Ayyubi, R.H.A.L.; Altalhi, W.A.; Atalla, A.A.A. Impact of COVID-19 on psychological and academic performance of medical students in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 3857–3862. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, P.; Briant, S. Predicting academic success: A longitudinal study of university design students. Int. J. Art. Des. Educ. 2021, 40, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talsma, K.; Robertson, K.; Thomas, C.; Norris, K. COVID-19 Beliefs, Self-Efficacy and Academic Performance in First-year University Students: Cohort Comparison and Mediation Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 643408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, D. Importance of Communication in Teaching Learning Process Ms Deepti Rawat Research Scholar Shobhit University Meerut. Sch. Res. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2016, 4, 3058–3063. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhahi, M.I.; Akil, S.; Zaidi, U.; Mortada, E.; Awad, S.; Awaji, N. Al Effect of resilience on health-related quality of life during the covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrabissa, G.; Simpson, S.G. Psychological Consequences of Social Isolation During COVID-19 Outbreak. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.P.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Pollak, T.A.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Zandi, M.S.; Lewis, G.; David, A.S. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Responses | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | <21 | 118 (41.1) |

| ≥21 | 169 (58.9) | |

| 20.81 ± 1.4 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 281 (97.9) |

| Married | 6 (2.1) | |

| Perceived socioeconomic status | Low | 16 (5.6) |

| Middle | 243 (84.7) | |

| High | 28 (9.8) | |

| Level | 4 | 83 (28.9) |

| 6 | 95 (33.1) | |

| 8 | 100 (34.8) | |

| Higher | 9 (3.1) | |

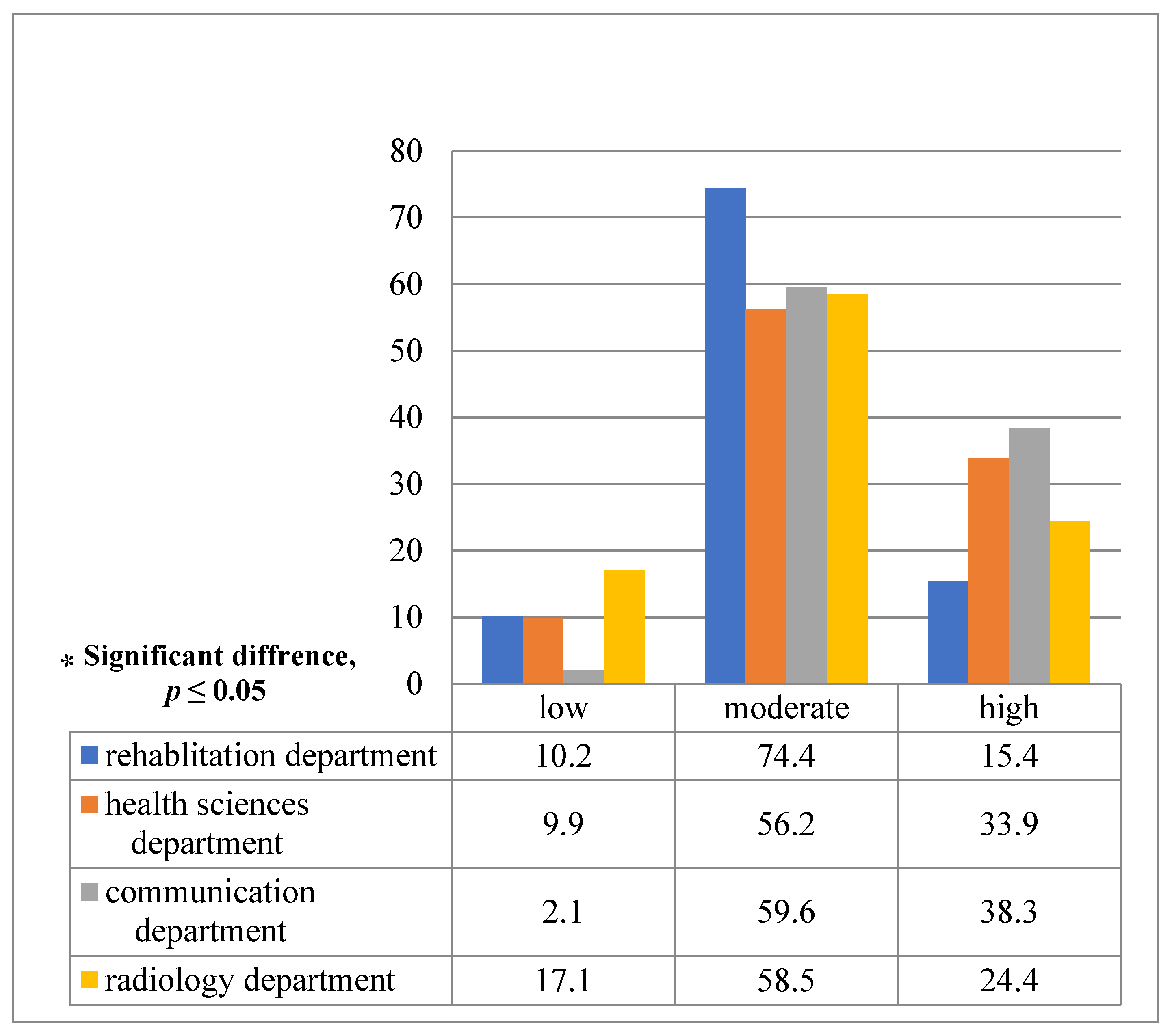

| Department | Health sciences | 78 (27.2) |

| Rehabilitation | 121 (42.2) | |

| Communication | 47 (16.4) | |

| Radiology | 41 (14.3) | |

| GPA | <4.5 | 125 (43.6) |

| ≥4.5 | 162 (56.4) | |

| 4.48 ± 0.32 | ||

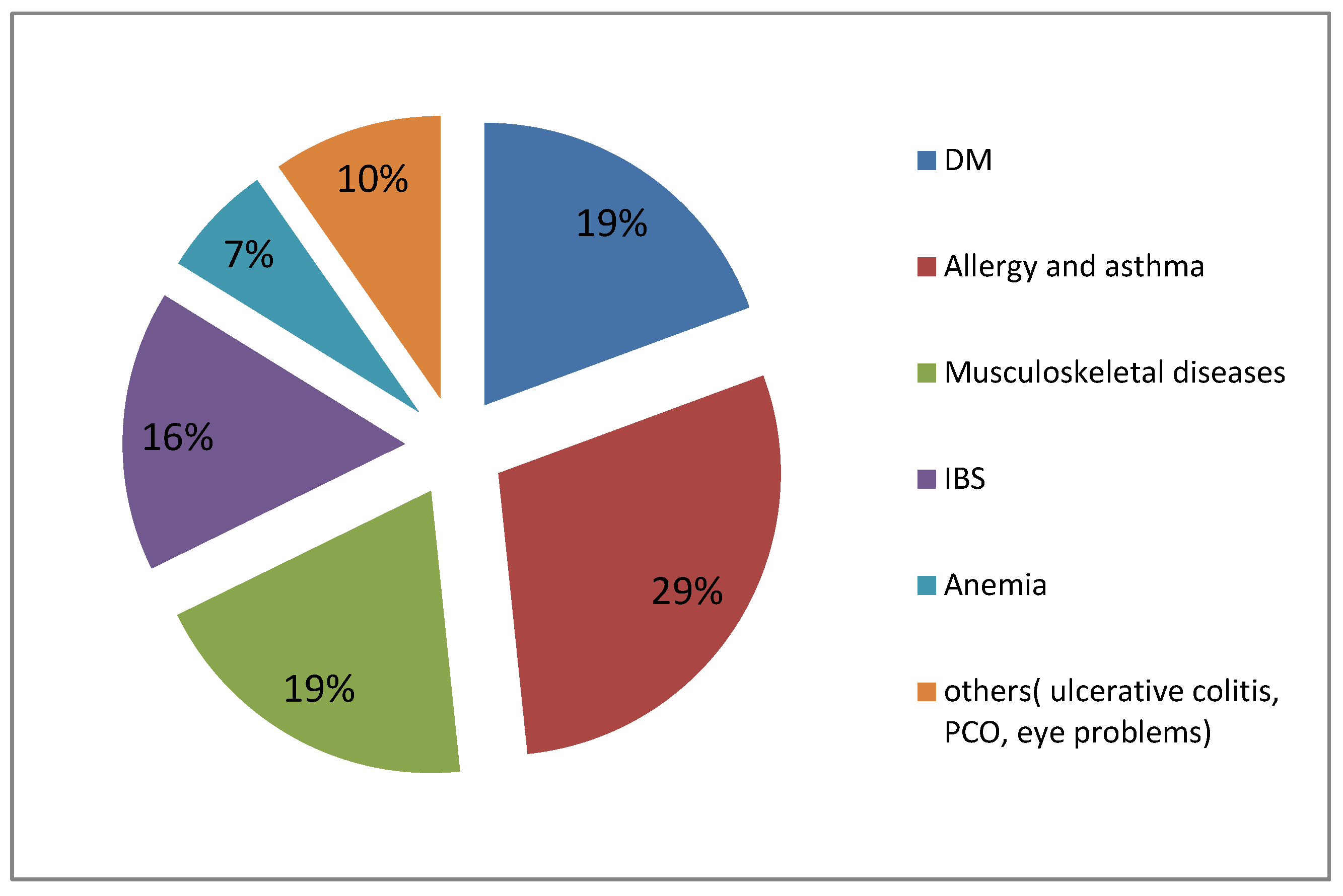

| Physical health issues | Absent | 257 (89.5) |

| Present | 30 (10.5) | |

| Psychological issues | Absent | 230 (80.1) |

| Present | 57 (19.9) | |

| Infected with COVID-19 | No | 168 (58.5) |

| Yes | 119 (41.5) | |

| Hospitalized | No | 112 (94.1) |

| Yes | 7 (5.9) | |

| Family members infected | No | 80 (27.9) |

| Yes | 207 (72.1) | |

| Total | 287 (100.0) | |

| Scales/Subscales | Items | M | SD | Mdn | IQR | MIN–MAX | Cronbach’s α Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GD | 6 | 18.6 | 5.04 | 18.6 | 6 | 6–30 | 0.74 |

| Ms | 6 | 18.3 | 4.94 | 18 | 7 | 6–30 | 0.84 |

| IP | 6 | 19.3 | 4.60 | 19 | 5 | 6–30 | 0.85 |

| PS | 6 | 16.7 | 4.59 | 17 | 5 | 6–30 | 0.78 |

| PRCA | 24 | 72.8 | 16.69 | 73 | 21 | 24–119 | 0.82 |

| RSE | 10 | 24.3 | 2.14 | 25 | 3 | 17–32 | 0.80 |

| Characteristics | Responses | PRCA Mdn (IQR) | SUBSCALES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GD Mdn (IQR) | Ms Mdn (IQR) | PS Mdn (IQR) | PI Mdn (IQR) | RSE | |||

| Age groups (y) | <21 | 73 (17.3) | 19 (5.5) | 18 (6) | 17 (5) | 19 (5) | 25 (3) |

| ≥21 | 73 (22) | 19 (7) | 18 (7.5) | 17 (6) | 19 (5) | 24 (3) | |

| Test | 9722.000 (−0.36) | 9766.000 (−0.297) | 9480.500 (−0.712) | 9017.000 (−1.385) | 9916.500 (−0.079) | 9292.000 (−0.996) | |

| p Value | 0.719 | 0.766 | 0.477 | 0.166 | 0.937 | 0.319 | |

| Marital status | Single | 73 (20) | 19 (6) | 18 (6.5) | 17 (5.5) | 19 (5) | 25 (3) |

| Married | 90 (36.4) | 25 (12.3) | 24(12.25) | 18.5 (8) | 22 (5.25) | 26 (3) | |

| Test | 470.500 (−1.85) U | 484.0000 (−1.8) | 524.500 (−1.59) | 573.500 (−1.35) | 358.000 (−2.42) | 525.500 (−1.6) | |

| p Value | 0.05 * | 0.073 | 0.112 | 0.179 | 0.016 * | 0.11 | |

| Perceived socioeconomic status | Low | 68 (31) | 16 (3.75) | 16.5 (10) | 17 (10.75) | 17 (4.75) | 24 (3) |

| Intermediate | 73 (19) | 19 (6) | 18 (7) | 17 (5) | 19 (4) | 25 (3) | |

| High | 72 (21.5) | 18 (8.5) | 18 (9.25) | 16.5 (7.25) | 19 (8.5) | 25 (2) | |

| Test | 2.612 (2) H | 2.860 (2) H | 0.976 (2) H | 1.507 (2) H | 3.098 (2) H | 6.330 (2) H | |

| p Value | 0.271 | 0.239 | 0.614 | 0.471 | 0.213 | 0.042 * | |

| GPA | 72 (20.25) | 19 (7) | 18 (8) | 17 (6) | 19 (5) | 25 (2.25) | |

| 73 (19) | 19 (6.5) | 18 (6) | 17 (5) | 19 (5.5) | 24 (3) | ||

| Test | 9461.500 (−0.95) U | 9746.500 (−0.545) | 9435.500 (−0.993) | 9680.000 (−0.641) | 9859.000 (−0.383) | 9882.000 (−0.354) | |

| p Value | 0.341 | 0.586 | 0.321 | 0.522 | 0.702 | 0.723 | |

| Physical/health issues | Absent | 73 (19) | 19 (6) | 18 (7) | 17 (5.5) | 19 (5) | 25 (3) |

| Present | 73 (19.75) | 18.5 (5.7) | 18 (8.25) | 16.5 (4.5) | 19.5 (6.25) | 24 (3) | |

| Test | 3733.000 (−0.28) | 3747.500 (−0.25) | 3696.500 (−0.37) | 3452.500 (−0.94) | 3753.000 (−0.24) | 3331.500 (−1.24) | |

| p Value | 0.777 | 0.802 | 0.711 | 0.347 | 0.812 | 0.217 | |

| Psychological issues | Absent | 73 (19) | 19 (6.25) | 18 (7) | 17 (5.5) | 19 (5) | 25 (3) |

| Present | 73 (23) | 18 (7.5) | 18 (7.5) | 17 (4.5) | 19 (5) | 24 (3.5) | |

| Test | 5816.500 (−1.32) | 5614.500 (−1.682) | 5857.000 (−1.249) | 6073.500 (−0.862) | 5654.500 (−1.611) | 6068.500 (−0.880) | |

| p Value | 0.188 | 0.093 | 0.211 | 0.389 | 0.107 | 0.379 | |

| Infected with COVID-19 | No | 73 (19.5) | 19 (6.75) | 18 (6) | 17 (5) | 19 (5) | 25 (2) |

| Yes | 73 (23) | 18 (7) | 18 (7) | 17 (7) | 19 (5) | 25 (2) | |

| Test | 9970.500 (−0.04) | 9593.500 (−0.583) | 9501.000 (−0.718) | 9191.000 (−1.167) | 9805.500 (−0.276) | 9384.000 (−0.897) | |

| p Value | 0.971 | 0.560 | 0.473 | 0.243 | 0.783 | 0.370 | |

| Hospitalized | No | 73 (23) | 18 (7) | 18 (8) | 17.5 (7) | 20 (5.75) | 25 (2) |

| Yes | 73 (7) | 19 (2) | 18 (5) | 17 (5) | 19 (1) | 23 (2) | |

| Test | 366.500 (−0.29) | 371.500 (−0.232) | 333.000 (−0.669) | 346.000 (−0.522) | 334.500 (−0.651) | 212.500 (−2.060) | |

| p Value | 0.773 | 0.816 | 0.504 | 0.602 | 0.515 | 0.039 * | |

| Infected Family members: | No | 73 (15.5) | 18 (5.75) | 18 (6.5) | 17 (4) | 19 (3) | 25 (3) |

| Yes | 73 (22) | 19 (7) | 18 (7) | 17 (6) | 19 (5) | 25 (3) | |

| Test | 8123.500 (−0.25) | 8188.500 (−0.15) | 7921.500 (−0.57) | 7893.000 (−0.62) | 8141.000 (−0.22) | 8001.000 (−0.45) | |

| p Value | 0.804 | 0.884 | 0.568 | 0.538 | 0.825 | 0.653 | |

| Characteristics | Responses | PRCA Mdn (IQR) | Subscales | RSE Mdn (IQR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GD Mdn (IQR) | Ms Mdn (IQR) | PS Mdn (IQR) | PI Mdn (IQR) | ||||

| Department | RehabS (n = 78) | 73 (13.3) | 19 (5) | 18 (5) | 17 (5) | 19 (4) | 24 (2) |

| HS (n = 121) | 74 (24.5) | 19 (8.5) | 18 (7.5) | 17 (6) | 19 (6) | 25 (3) | |

| RS (n = 41) | 69 (24.5) | 17 (6) | 18 (9) | 16 (6.5) | 18 (7) | 24 (3) | |

| HCS (n = 47) | 75 (12) | 19 (7) | 18 (7) | 18 (4) | 20 (5) | 25 (2) | |

| Test | 8.18 H&B | 5.165 H | 4.35H | 14.61H&B | 4.58 H | 6.51 H | |

| p Value | 0.04 * | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.002 * | 0.21 | 0.09 | |

| Group differences | HCS > RS 0.05 * | HCS > RS 0.003 * | |||||

| Characteristics | Responses | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PRCA | Low | 29 (9.8) |

| Average | 178 (62.0) | |

| High | 81 (28.2) | |

| RSE | Low | 75 (26.1) |

| High | 212 (73.9) |

| Correlation Matrix for the Study Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | GPA | Age | RSE | PRCA | GD | MS | IP | PS |

| GPA | 1 | |||||||

| Age | −0.042 | 1 | ||||||

| RSE | 0.065 | −0.65 | 1 | |||||

| PRCA | −0.089 | −0.028 | −0.195 ** | 1 | ||||

| GD | −0.021 | 0.011 | 0.178 ** | 0.859 ** | 1 | |||

| MS | −0.022 | −0.025 | −0.179 ** | 0.910 ** | 0.738 ** | 1 | ||

| IP | 0.039 | 0.036 | 0.144 * | 0.841 ** | 0.648 ** | 0.707 ** | 1 | |

| PS | 0.067 | −0.064 | −0.165 ** | 0.752 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.643 ** | 0.531 ** | 1 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Β | T | Sig. | B | Β | T | Sig. | B | β | T | Sig. | ||

| Constant | 4.270 | 11.986 | 0.000 | 4.012 | 9.516 | 0.000 | 4.010 | 9.490 | 0.000 | ||||

| Predictors | Age | −0.005 | −0.022 | −0.379 | 0.705 | −0.004 | −0.018 | −0.307 | 0.759 | −0.004 | −0.019 | −0.312 | 0.756 |

| Marital status | 0.122 | 0.055 | 0.905 | 0.366 | 0.115 | 0.052 | 0.857 | 0.392 | 0.116 | 0.052 | 0.858 | 0.392 | |

| Social class | 0.034 | 0.042 | 0.707 | 0.480 | 0.026 | 0.032 | 0.532 | 0.595 | 0.026 | 0.032 | 0.533 | 0.595 | |

| Department | 0.047 | 0.144 | 2.379 | 0.018 | 0.046 * | 0.143 | 2.358 | 0.019 * | 0.046 | 0.143 | 2.354 | 0.019 * | |

| Physical/health issues | 0.036 | 0.035 | 0.586 | 0.558 | 0.042 | 0.040 | 0.676 | 0.500 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.662 | 0.509 | |

| Psychological issues | 0.039 | 0.048 | 0.809 | 0.419 | 0.042 | 0.053 | 0.878 | 0.381 | 0.042 | 0.052 | 0.871 | 0.385 | |

| Infected with COVID-19 | −0.069 | −0.106 | −1.669 | 0.096 | −0.070 | −0.108 | −1.705 | 0.089 | −0.070 | −0.107 | −1.683 | 0.094 | |

| Relative infected with COVID-19 | 0.017 | 0.024 | 0.387 | 0.699 | 0.018 | 0.026 | 0.412 | 0.681 | 0.018 | 0.025 | 0.403 | 0.688 | |

| PRCA | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.185 | 0.854 | 5.518 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.998 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.007 | 0.995 | |

| Moderators | RSE | 0.010 | 0.070 | 1.144 | 0.254 | 0.011 | 0.071 | 1.151 | 0.251 | ||||

| Interaction | PRCA × RSE | −0.003 | −0.009 | −0.148 | 0.883 | ||||||||

| Model Statistics | F | 1.020 * | 1.034 | 0.944 | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.063 | 0.096 | 0.096 | ||||||||||

| ∆R2 | 0.063 | 0.023 | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Description | Example/Main points | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Communication patterns | Before pandemic | The quality of expressive communication in general before pandemic. | “I had been a talkative person”. |

| After pandemic | Difficulties in Communication pattern after pandemic. | “I lost the basic skills of conversation maybe”. | ||

| 2 | Psychological impact | Psychological Issue | Psychological issue in communication after the COVID-19 pandemic. | “I am sensitive now”. |

| Anxiety triggering event | Circumstance causing nervousness and stress. | Presentation, class discussion, conversing with a new acquaintance, general conversation. | ||

| Problem-solving | The problem-solving approaches used by the participants. | “I wish I can find the solution for my anxiety”. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Awaji, N.; Zaidi, U.; Awad, S.S.; Alroqaiba, N.; Aldhahi, M.I.; Alsaleh, H.; Akil, S.; Mortada, E.M. Moderating Effects of Self-Esteem on the Relationship between Communication Anxiety and Academic Performance among Female Health College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13960. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113960

Al Awaji N, Zaidi U, Awad SS, Alroqaiba N, Aldhahi MI, Alsaleh H, Akil S, Mortada EM. Moderating Effects of Self-Esteem on the Relationship between Communication Anxiety and Academic Performance among Female Health College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):13960. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113960

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Awaji, Nisreen, Uzma Zaidi, Salwa S. Awad, Nouf Alroqaiba, Monira I. Aldhahi, Hadel Alsaleh, Shahnaz Akil, and Eman M. Mortada. 2022. "Moderating Effects of Self-Esteem on the Relationship between Communication Anxiety and Academic Performance among Female Health College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 13960. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113960

APA StyleAl Awaji, N., Zaidi, U., Awad, S. S., Alroqaiba, N., Aldhahi, M. I., Alsaleh, H., Akil, S., & Mortada, E. M. (2022). Moderating Effects of Self-Esteem on the Relationship between Communication Anxiety and Academic Performance among Female Health College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13960. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113960