Exploring the Intersections of Migration, Gender, and Sexual Health with Indonesian Women in Perth, Western Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Team

2.2. Participants

2.3. Participant Characteristics

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

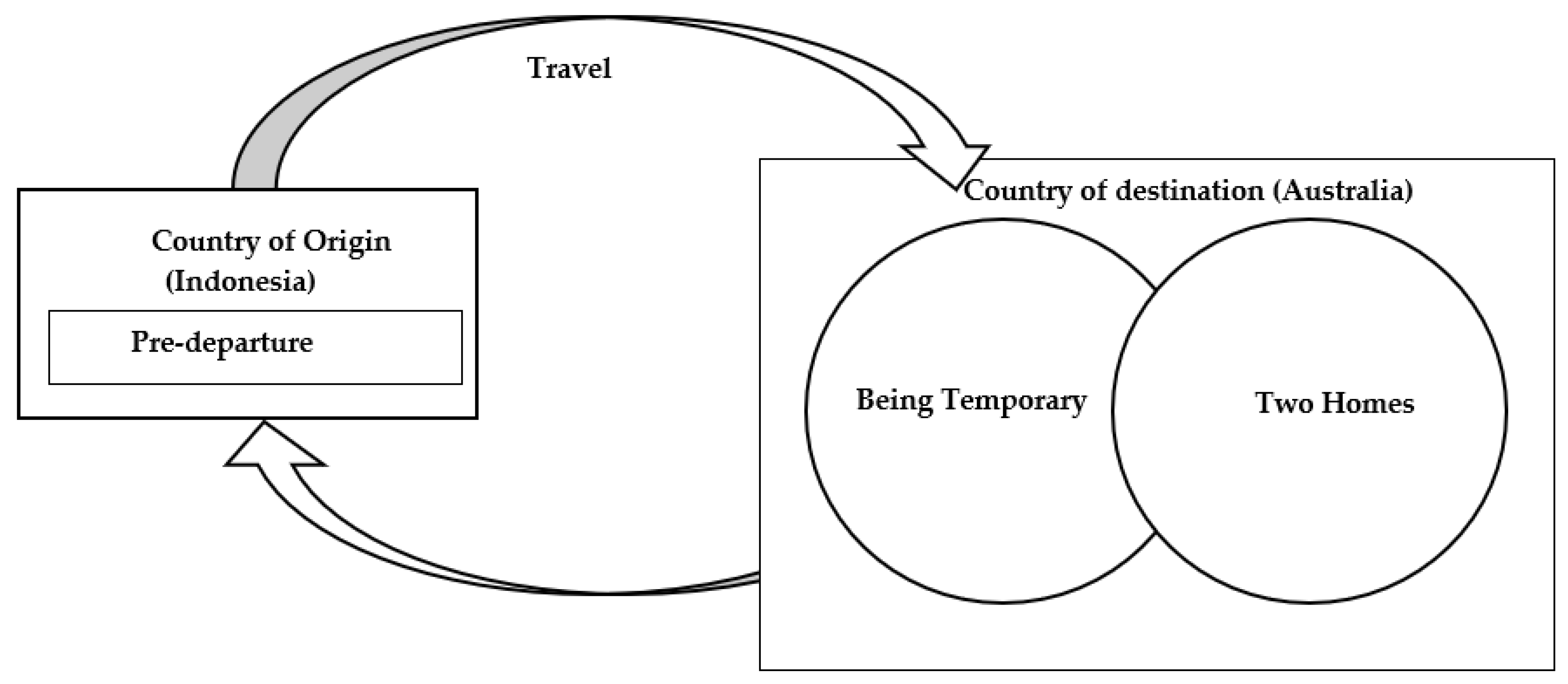

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Departure and Travel: Motivations, Support, and Gender Roles

3.1.1. ‘I’m a Little Curious’: Expectations of Marriage, Sexual Naivety, and Self-Taught Sexual Education

“In Indonesia, it’s like a culture when a girl—just better to stay at home. If you’re a boy, then you can go. I mean we (girls) have to like, you know, be more protected.”—Student visa, 2019

“You can only learn it (sexual health) from your friends and internet… you know, boys would bring the porn magazine. And then the comic, the porn—soft porn comic book and then they share it to themselves and then even though you are a female, you kinda like come across to them and will be like, “Oh, can I see that as well?” And you kinda,—you know, learn from them (porn magazines)”—Permanent resident, 2007

3.1.2. ‘You Already Know the Culture’: Maintaining Gender Roles in Migration

“He came here and started PhD.… He’s not quite good in cooking. He’s not that quite good with other household stuff… I feel that I don’t want to lose my career. I love to work. I love to become a lecturer. And sadly, I have to leave that, I have to resign from that position… I really regret that.”—Student visa, 2004

3.1.3. ‘Moving Here Is So Liberating’: Challenging Traditional Gender Roles

“Yeah. I wanted to go to university. (Parents) say, “But you’re a girl.” You know, they still think that boys deserve more education than girls. … you get married and then, you know—just like that. But for boys, they’re willing to pay for their education… But then I think years after that, I can go to the university by myself.”—Student visa, 2018

3.2. Country of Destination: Being ‘Temporary’

3.2.1. ‘You Can Disappear’: Temporary Visas Limiting Help Seeking and Reinforcing Gender Roles

“And then even when I got home that night there was like bruise marks on me where he grabbed me, my mum still didn’t call the cops. … everyone just like ‘Oh, you can disappear!’ and of course all Asians have heard horror stories from America. We don’t know if Australia is the same. Getting deported.”—Permanent resident, 2012

3.2.2. ‘Good Girls’: Maintaining Gendered Expectations of Sexuality

“So when I start to have that, um, to have sex and everything with my husband, that’s when I start learning things related to that sexual stuff. But luckily, I don’t have any problem with the healthy side, especially in my—that part (vaginal area). [laughs] See. You noticed me. I still cannot say that.”—Student visa, 2004

“You know, Indonesia has a history with patriarchal culture where men become a leader of the family, the decision-maker, the breadwinner, and wives should respect the husband… But at some point, there’s some value that we still keep because of our religion as well because we have to respect our husband… as long as my husband still love me, still take care of my children, still responsible to the family, so, if he has lust (sexual intercourse) with somebody else, but put the wife more priority, well, I think, that’s okay.”—Student visa, 2016

3.2.3. ‘They Talking behind me and How Bad I am’: How Anticipating Return Influences Sexuality While in Australia

3.3. Country of Destination: Two Homes

3.3.1. ‘Being a Banana’: Becoming More Open-Minded about Sexuality

“So yeah, and like moving here everything is so liberated and I’ve never really explored sexually and learned proper sexual health stuff until I moved here.”—Permanent resident, 2012

3.3.2. ‘White Knights’: Relationships with Australians Supporting Changing Gender Roles

“Because for me, I think, if we are married, for one, [Indonesian husband] like take away our freedom. I don’t want to live like that.”—Student visa, 2019

“Australians are super chilled and friendly and open about things. If I were to talk about things with Asian Indonesians mostly here, they tend to be a bit almost innocent like, close-minded innocent like. I would mention about the things (sexual behaviour)… and they’d look at me as if I’ve committed a great taboo. Yeah, so that’s why I’m not really close to Indonesians here.”—Permanent resident, 2012

3.3.3. ‘Open-Minded’: Being in Australia, Freedom of Sexuality and Sexual Health Risk

“When you have a kid, you have no freedom… when we have kid, we will lose our future. We cannot go finish our study. We cannot go working... But then with, you know, health issue (STI)… If you take your medicine and after then go check up in a doctor and after medicine, it doesn’t really like, affect your future, kind of thing? But then if you’re pregnant, it’s kinda like my future is ruined... there is always, always a moral judgment like people judge you and whatever, but then you can actually still, as a female, you can apply job and then they wouldn’t ask you for that (STI results). You get a job functioning as a human being, normal human being according to them. But then if you’re a pregnant woman? No. The doors close. At all. So you have no future.”—Permanent resident, 2007

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zimmerman, C.; Kiss, L.; Hossain, M. Migration and health: A framework for 21st century policy-making. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1001034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.; Crawford, G.; Maycock, B.; Lobo, R. Socioecological Factors Influencing Sexual Health Experiences and Health Outcomes of Migrant Asian Women Living in ‘Western’ High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, S.; Hallett, J.; Gray, C.; Lobo, R.; Crawford, G. What Works? Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Blood-Borne Viruses in Migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa, Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia Living in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet Public Health. No public health without migrant health. Lancet Public Health 2018, 3, e259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, I.; Aldridge, R.W.; Devakumar, D.; Orcutt, M.; Burns, R.; Barreto, M.L.; Dhavan, P.; Fouad, F.M.; Groce, N.; Guo, Y.; et al. The UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: The health of a world on the move. Lancet 2018, 392, 2606–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossin, M.Z. International migration and health: It is time to go beyond conventional theoretical frameworks. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e001938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markides, K.S.; Rote, S. The Healthy Immigrant Effect and Aging in the United States and Other Western Countries. Gerontologist 2018, 59, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health 2018; Cat. No. AUS 221; Australia’s Health Series No. 16; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jatrana, S.; Richardson, K.; Pasupuleti, S.S.R. Investigating the dynamics of migration and health in Australia: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Popul. 2018, 34, 519–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A.S.; Antoniades, J.; Brijnath, B. The symbolic mediation of patient trust: Transnational health-seeking among Indian-Australians. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 235, 112359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.A.; Basten, A.; Frattini, C. Migration: A Social Determinant of the Health of Migrants; International Organization for Migration: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, H.; Holmes, S.M.; Madrigal, D.S.; Young, M.-E.D.; Beyeler, N.; Quesada, J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmusi, D.; Borrell, C.; Benach, J. Migration-related health inequalities: Showing the complex interactions between gender, social class and place of origin. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes, E.A.; Miranda, P.Y.; Abdulrahim, S. More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabete, A.C. Examining Migrants’ Health from a Gender Perspective. In The Psychology of Gender and Health; Pilar Sanchez-Lopez, M., Gras, R.M.L., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, E.-O.; Yang, K. Theories on Immigrant Women’s Health. Health Care Women Int. 2006, 27, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkiouleka, A.; Huijts, T. Intersectional migration-related health inequalities in Europe: Exploring the role of migrant generation, occupational status & gender. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 267, 113218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldin, A.; Chakraverty, D.; Baumeister, A.; Monsef, I.; Noyes, J.; Jakob, T.; Seven, Ü.S.; Anapa, G.; Woopen, C.; Kalbe, E. Gender differences in health literacy of migrants: A synthesis of qualitative evidence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 4, CD013302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llacer, A.; Zunzunegui, M.V.; del Amo, J.; Mazarrasa, L.; Bolumar, F. The contribution of a gender perspective to the understanding of migrants’ health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61 (Suppl. S2), ii4–ii10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, C.; Gifford, S.; Temple-Smith, M. The cultural and social shaping of sexual health in Australia. In Sexual Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach; Temple-Smith, M., Ed.; IP Communications: Melbourne, Australia, 2014; pp. 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, M.T.; Gifford, S.M. Social Change, Migration and Sexual Health: Chilean Women in Chile and Australia. Women Health 2004, 38, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multicultural Women’s Health Australia. Sexual and Reproductive Health Data Report; Multicultural Women’s Health Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Keygnaert, I.; Guieu, A.; Ooms, G.; Vettenburg, N.; Temmerman, M.; Roelens, K. Sexual and reproductive health of migrants: Does the EU care? Health Policy 2014, 114, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z.B.; Dune, T.; Perz, J. Culturally and linguistically diverse women’s views and experiences of accessing sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: A systematic review. Sex. Health 2016, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M.T.; Gifford, S.M. Narratives, Culture and Sexual Health: Personal Life Experiences of Salvadorean and Chilean Women Living in Melbourne, Australia. Health 2001, 5, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Torres, L.; Gonzalez-Vazquez, T.; Fleming, P.J.; González-González, E.L.; Infante-Xibille, C.; Chavez, R.; Barrington, C. Transnationalism and health: A systematic literature review on the use of transnationalism in the study of the health practices and behaviors of migrants. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 183, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adanu, R.M.; Johnson, T.R. Migration and women’s health. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2009, 106, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. HIV Blueprint. Available online: https://www.afao.org.au/our-work/hiv-blueprint/ (accessed on 13 February 2018).

- Crawford, G.; Lobo, R.; Brown, G.; Langdon, P. HIV and Mobility in Australia: Road Map for Action; Western Australian Centre for Health Promotion Research and Australian Research Centre in Sex Health and Society: Perth, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, A.; Brown, G.; McDonald, A.; Korner, H. Transmission and Prevention of HIV among Heterosexual Populations in Australia. Aids Educ. Prev. 2014, 26, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.; Lobo, R.; Narciso, L.; Oudih, E.; Gunaratnam, P.; Thorpe, R.; Crawford, G. Why I Can’t, Won’t or Don’t Test for HIV: Insights from Australian Migrants Born in Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.; Crawford, G.; Lobo, R.; Maycock, B. Getting the right message: A content analysis and application of the health literacy INDEX tool to online HIV resources in Australia. Health Educ. Res. 2020, 36, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health Australian Government. Eighth National HIV Strategy 2018–2022; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Rade, D.; Crawford, G.; Lobo, R.; Gray, C.; Brown, G. Sexual Health Help-Seeking Behavior among Migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia living in High Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.; Crawford, G.; Lobo, R.; Maycock, B. Co-Designing an Intervention to Increase HIV Testing Uptake with Women from Indonesia At-Risk of HIV: Protocol for a Participatory Action Research Study. Methods Protoc. 2019, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Migration, Australia. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/migration-australia/2018-19 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Baum, F.; MacDougall, C.; Smith, D. Participatory action research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A.G.D. Researcher Positionality—A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research—A New Researcher Guide. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 2020, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, V. Thinking about the Coding Process in Qualitative Data Analysis. Qual. Rep. 2018, 23, 2850–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software; Version 11; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Victoria, Australia, 2016.

- Ryan, G.W.; Bernard, H.R. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 2003, 15, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, C.; Gifford, S. “It is Good to Know Now…Before it’s Too Late”: Promoting Sexual Health Literacy Amongst Resettled Young People with Refugee Backgrounds. Sex. Cult. 2009, 13, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, A. Understanding Women and Migration: A Literature Review; Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Anicha, C.L.; Bilen-Green, C.; Green, R. A policy paradox: Why gender equity is men’s work. J. Gend. Stud. 2020, 29, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, C.; Gifford, S. Narratives of sexual health risk and protection amongst young people from refugee backgrounds in Melbourne, Australia. Cult. Health Sex. 2010, 12, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchard, A.; Laurence, C.; Stocks, N. Female International students and sexual health: A qualitative study into knowledge, beliefs and attitudes. Aust. Fam. Physician 2011, 40, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, C.P.; Kaflay, D.; Dowshen, N.; Miller, V.A.; Ginsburg, K.R.; Barg, F.K.; Yun, K. Attitudes and Beliefs Pertaining to Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Unmarried, Female Bhutanese Refugee Youth in Philadelphia. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, A.; Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J. Constructions and experiences of sexual health among young, heterosexual, unmarried Muslim women immigrants in Australia. Cult. Health Sex. 2014, 16, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poljski, C.; Quiazon, R.; Tran, C. Ensuring rights: Improving access to sexual and reproductive health services for female international students in Australia. J. Int. Stud. 2014, 4, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R. ‘His visa is made of rubber’: Tactics, risk and temporary moorings under conditions of multi-stage migration to Australia. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2021, 22, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Multicultural Interests. Search Diversity WA. Available online: https://www.omi.wa.gov.au/resources-and-statistics/search-diversity-wa (accessed on 16 June 2022).

| Year of Birth * | Number of Women |

|---|---|

| 1990–1999 | 1 |

| 1980–1989 | 5 |

| 1960–1979 | 2 |

| Religion | |

| Islam | 3 |

| Christian | 3 |

| Hindu | 1 |

| Buddhist | 1 |

| Catholic | 1 |

| Language(s) spoken | |

| Indonesian | 9 |

| Javanese | 1 |

| Sundanese | 1 |

| Balinese | 1 |

| Mandarin | 1 |

| Self-reported English Proficiency | |

| Very well | 4 |

| Well | 4 |

| Not well | 1 |

| Year of arrival in Australia | |

| 2015–2018 | 6 |

| 2010–2014 | 2 |

| 2004–2009 | 1 |

| Status in Australia | |

| Permanent resident | 3 |

| Student visa | 5 |

| Tourist visa | 1 |

| Education | |

| Masters | 2 |

| University degree | 5 |

| Year 12 | 1 |

| Some high school | 1 |

| Relationship Status | |

| Married | 7 |

| Unmarried | 1 |

| In a relationship | 1 |

| Children | |

| Yes | 7 |

| No | 2 |

| HIV test | |

| Yes | 4 |

| No | 5 |

| Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Pre-departure and travel: motivations, support, and gender roles | ‘I’m a little curious’: expectations of marriage, sexual naivety, and self-taught sexual education |

| ‘You already know the culture’: maintaining gender roles in migration | |

| ‘Moving here is so liberating’: challenging traditional gender roles | |

| Country of destination: being ‘Temporary’ | ‘You can disappear’: temporary visas limiting help seeking and reinforcing gender roles |

| ‘Good girls’: maintaining gendered expectations of sexuality | |

| ‘They talking behind me and how bad I am’: how anticipating return influences sexuality while in Australia | |

| Country of destination: two homes | ‘Being a Banana’: becoming more open-minded about sexuality |

| ‘White knights’: relationships with Australians supporting changing gender roles | |

| ‘Open-minded’: being in Australia, freedom of sexuality and sexual health risk |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gray, C.; Crawford, G.; Maycock, B.; Lobo, R. Exploring the Intersections of Migration, Gender, and Sexual Health with Indonesian Women in Perth, Western Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013707

Gray C, Crawford G, Maycock B, Lobo R. Exploring the Intersections of Migration, Gender, and Sexual Health with Indonesian Women in Perth, Western Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013707

Chicago/Turabian StyleGray, Corie, Gemma Crawford, Bruce Maycock, and Roanna Lobo. 2022. "Exploring the Intersections of Migration, Gender, and Sexual Health with Indonesian Women in Perth, Western Australia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013707

APA StyleGray, C., Crawford, G., Maycock, B., & Lobo, R. (2022). Exploring the Intersections of Migration, Gender, and Sexual Health with Indonesian Women in Perth, Western Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013707