The Effectiveness of Ultraviolet-C (UV-C) Irradiation on the Viability of Airborne Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

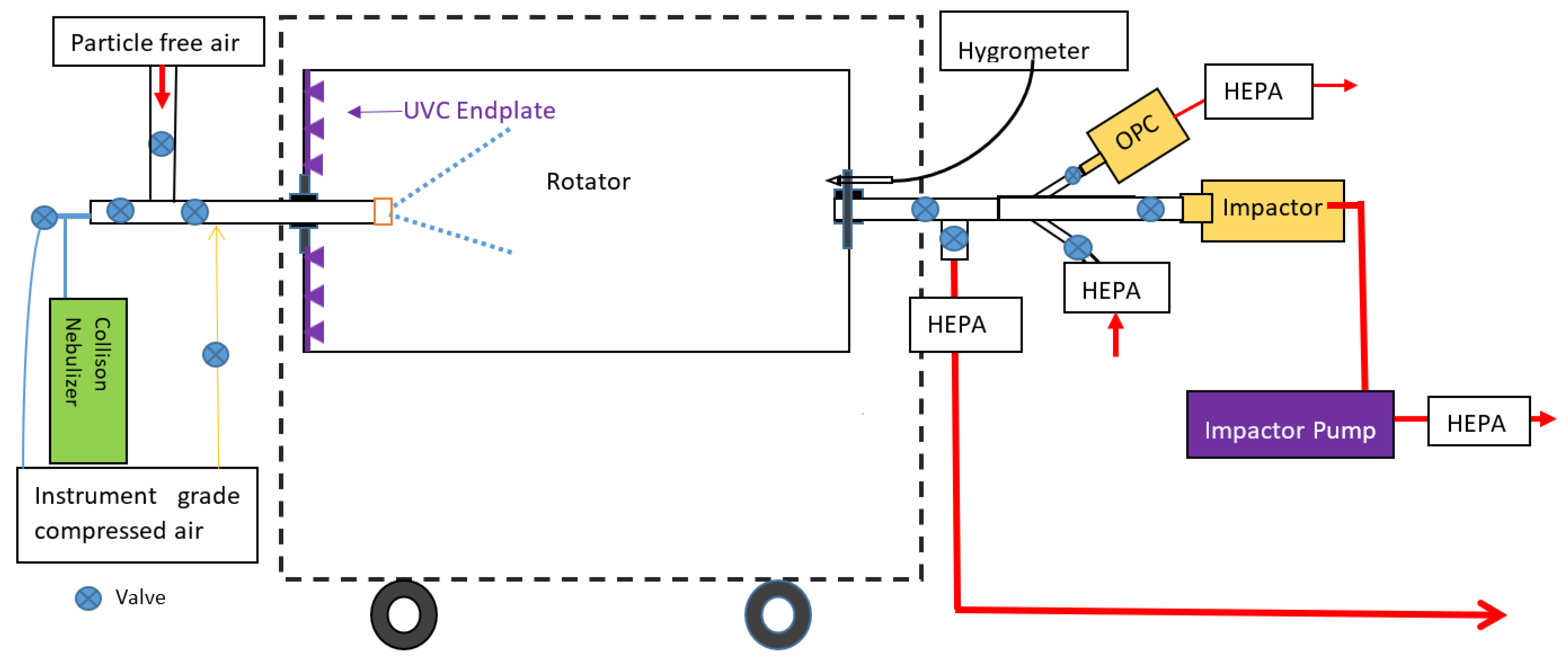

2.1. TARDIS-Rotator and UV-C System

2.2. UV-C Validation

2.3. Relative Humidity and Temperature

2.4. Culture Preparations

2.5. Nebulization

2.6. Bioaerosol Sampling

2.7. Enumeration of Airborne Pa

2.8. Particle Size Measurements

2.9. Test Procedure

2.10. Core Experiments

2.11. Other Experiments

2.12. Statistical Analysis

2.13. Indoor Model

3. Results

3.1. General

3.2. Natural Decay and Total Reduction in Airborne Pa

3.3. UV-C Effectiveness

3.4. Other Experiments

3.5. Indoor Model Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Other Studies

4.2. Relevance to Infection Control in People with CF

4.3. Safety and Implementation

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Sullivan, B.P.; Freedman, S.D. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2009, 373, 1891–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, M.C.; Couet, W.; Olivier, J.C.; Pais, A.A.; Sousa, J.J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis lung disease and new perspectives of treatment: A review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 32, 1231–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahenthiralingam, E. Emerging cystic fibrosis pathogens and the microbiome. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2014, 15 (Suppl. S1), 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elborn, J.S. Identification and management of unusual pathogens in cystic fibrosis. J. R Soc. Med. 2008, 101 (Suppl. S1), S2–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, J.A.; Lewis, P.A.; Stanton, M.; Wilsher, J. Cystic fibrosis mortality and survival in the UK: 1947–003. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 29, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, R.H.; Szczesniak, R.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; Bilton, D. Up-to-date and projected estimates of survival for people with cystic fibrosis using baseline characteristics: A longitudinal study using UK patient registry data. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2018, 17, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, S.; Caruso, M.; Ruseckaite, R.; BobotA, S.B.N. The Australian Cystic Fibrosis Data Registry Annual Report 2020; Report No. 22; Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rachel, M.; Topolewicz, S.; Śliwczyński, A.; Galiniak, S. Managing Cystic Fibrosis in Polish Healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CF Australia. Infection Control Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis Patients and Carers; CF Australia: Burwood, NSW, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez, C.; Pena, C.; Arch, O.; Dominguez, M.A.; Tubau, F.; Juan, C.; Gavalda, L.; Sora, M.; Oliver, A.; Pujol, M.; et al. A large sustained endemic outbreak of multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A new epidemiological scenario for nosocomial acquisition. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiman, L.; Siegel, J.; Cystic Fibrosis, F. Infection control recommendations for patients with cystic fibrosis: Microbiology, important pathogens, and infection control practices to prevent patient-to-patient transmission. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2003, 24, S6–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.M.; Grogono, D.M.; Greaves, D.; Foweraker, J.; Roddick, I.; Inns, T.; Reacher, M.; Haworth, C.S.; Curran, M.D.; Harris, S.R.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing to identify transmission of Mycobacterium abscessus between patients with cystic fibrosis: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2013, 381, 1551–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.R.; Pressler, T.; Ridderberg, W.; Johansen, H.K.; Skov, M. Achromobacter species in cystic fibrosis: Cross-infection caused by indirect patient-to-patient contact. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2013, 12, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, T.J.; Ramsay, K.A.; Hu, H.; Marks, G.B.; Wainwright, C.E.; Bye, P.T.; Elkins, M.R.; Robinson, P.J.; Rose, B.R.; Wilson, J.W.; et al. Shared Pseudomonas aeruginosa genotypes are common in Australian cystic fibrosis centres. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 41, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifton, I.J.; Peckham, D.G. Defining routes of airborne transmission of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in people with cystic fibrosis. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2010, 4, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffer, K. Epidemiology of infection and current guidelines for infection prevention in cystic fibrosis patients. J. Hosp. Infect. 2015, 89, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainwright, C.E.; France, M.W.; O’Rourke, P.; Anuj, S.; Kidd, T.J.; Nissen, M.D.; Sloots, T.P.; Coulter, C.; Ristovski, Z.; Hargreaves, M.; et al. Cough-generated aerosols of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Gram-negative bacteria from patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2009, 64, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knibbs, L.D.; Johnson, G.R.; Kidd, T.J.; Cheney, J.; Grimwood, K.; Kattenbelt, J.A.; O’Rourke, P.K.; Ramsay, K.A.; Sly, P.D.; Wainwright, C.E.; et al. Viability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cough aerosols generated by persons with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2014, 69, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.E.; Stockwell, R.E.; Johnson, G.R.; Ramsay, K.A.; Sherrard, L.J.; Kidd, T.J.; Cheney, J.; Ballard, E.L.; O’Rourke, P.; Jabbour, N.; et al. Cystic fibrosis pathogens survive for extended periods within cough-generated droplet nuclei. Thorax 2019, 74, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.M.; Grogono, D.M.; Rodriguez-Rincon, D.; Everall, I.; Brown, K.P.; Moreno, P.; Verma, D.; Hill, E.; Drijkoningen, J.; Gilligan, P.; et al. Emergence and spread of a human-transmissible multidrug-resistant nontuberculous mycobacterium. Science 2016, 354, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiman, L.; Siegel, J.D.; LiPuma, J.J.; Brown, R.F.; Bryson, E.A.; Chambers, M.J.; Downer, V.S.; Fliege, J.; Hazle, L.A.; Jain, M.; et al. Infection prevention and control guideline for cystic fibrosis: 2013 update. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2014, 35 (Suppl S1), S1–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Pickering, C.A.C.; Faragher, E.B.; Austwick, P.K.C.; Little, S.A.; Lawton, L. An Investigation of the Relationship between Microbial and Particulate Indoor Air-Pollution and the Sick Building Syndrome. Resp. Med. 1992, 86, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Driessche, K.; Hens, N.; Tilley, P.; Quon, B.S.; Chilvers, M.A.; de Groot, R.; Cotton, M.F.; Marais, B.J.; Speert, D.P.; Zlosnik, J.E. Surgical masks reduce airborne spread of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in colonized patients with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 897–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, M.E.; Stockwell, R.E.; Johnson, G.R.; Ramsay, K.A.; Sherrard, L.J.; Jabbour, N.; Ballard, E.; O’Rourke, P.; Kidd, T.J.; Wainwright, C.E.; et al. Face Masks and Cough Etiquette Reduce the Cough Aerosol Concentration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in People with Cystic Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, R.E.; Wood, M.E.; He, C.; Sherrard, L.J.; Ballard, E.L.; Kidd, T.J.; Johnson, G.R.; Knibbs, L.D.; Morawska, L.; Bell, S.C.; et al. Face Masks Reduce the Release of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Cough Aerosols When Worn for Clinically Relevant Periods. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 1339–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, N.G. The history of ultraviolet germicidal irradiation for air disinfection. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, T.; Vrahas, M.S.; Murray, C.K.; Hamblin, M.R. Ultraviolet C irradiation: An alternative antimicrobial approach to localized infections? Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2012, 10, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Beltr·n, J.A.; Barbosa-C·novas, G.V. Advantages and Limitations on Processing Foods by UV Light. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2004, 10, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, W.F.; Fair, G.M. Viability of B. Coli Exposed to Ultra-Violet Radiation in Air. Science 1935, 82, 280–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Kesavan, J.; Sagripanti, J.L. Germicidal UV Sensitivity of Bacteria in Aerosols and on Contaminated Surfaces. Aerosol. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kethley, T.W.; Branch, K. Ultraviolet lamps for room air disinfection. Effect of sampling location and particle size of bacterial aerosol. Arch. Environ. Health 1972, 25, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.L.; Knight, M.; Middlebrook, G. Ultraviolet susceptibility of BCG and virulent tubercle bacilli. Am. Rev. Respir Dis 1976, 113, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peccia, J.; Hernandez, M. UV-induced inactivation rates for airborne Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2004, 1, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.W.; Li, S.Y.; Huang, S.H.; Huang, C.K.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, C.C. Effects of ultraviolet germicidal irradiation and swirling motion on airborne Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Legionella pneumophila under various relative humidities. Indoor Air 2013, 23, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, G.; First, M.W.; Burge, H.A. Influence of relative humidity on particle size and UV sensitivity of Serratia marcescens and Mycobacterium bovis BCG aerosols. Tuber. Lung Dis. 2000, 80, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccia, J.; Werth, H.M.; Miller, S.; Hernandez, M. Effects of relative humidity on the ultraviolet induced inactivation of airborne bacteria. Aerosol. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, G.; Aliano, M.P.; Amagliani, G.; Magnani, M.; Brandi, G.; Pennino, C.; Schiavano, G.F. Airborne Microorganism Inactivation by a UV-C LED and Ionizer-Based Continuous Sanitation Air (CSA) System in Train Environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana Martins, C.P.; Xavier, C.S.F.; Cobrado, L. Disinfection methods against SARS-CoV-2: A systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2022, 119, 84–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.; Yang, M.; Marabella, I.A.; McGee, D.A.J.; Aboubakr, H.; Goyal, S.; Hogan, C.J., Jr.; Olson, B.A.; Torremorell, M. Greater than 3-Log Reduction in Viable Coronavirus Aerosol Concentration in Ducted Ultraviolet-C (UV-C) Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 4174–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, H.; Ito, M.; Furusawa, Y.; Yamayoshi, S.; Inoue, S.I.; Kawaoka, Y. A 265-Nanometer High-Power Deep-UV Light-Emitting Diode Rapidly Inactivates SARS-CoV-2 Aerosols. mSphere 2022, 7, e0094121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanOsdell, D.; Foarde, K. Defining the Effectiveness of UV Lamps Installed in Circulating Air Ductwork; Air-Conditioning and Refrigeration Technology Institute: Arlington, VA, USA; RTI International: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, S.N.; First, M.W. Fundamental Factors Affecting Upper-Room Ultraviolet Germicidal IrradiationÔÇöPart II. Predicting Effectiveness. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2007, 4, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.J.; Zheng, T.L.; Liu, J.X. Characterization, factors, and UV reduction of airborne bacteria in a rural wastewater treatment station. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Johnson, G.R.; Bell, S.C.; Knibbs, L.D. A Systematic Literature Review of Indoor Air Disinfection Techniques for Airborne Bacterial Respiratory Pathogens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, D.G. The effects of ultraviolet light on bacteria suspended in air. J. Bacteriol. 1940, 39, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noakes, C.J.; Fletcher, L.A.; Beggs, C.B.; Sleigh, P.A.; Kerr, K.G. Development of a numerical model to simulate the biological inactivation of airborne microorganisms in the presence of ultraviolet light. J. Aerosol Sci. 2004, 35, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggs, C.B.; Kerr, K.G.; Donnelly, J.K.; Sleigh, P.A.; Mara, D.D.; Cairns, G. The resurgence of tuberculosis in the tropics. An engineering approach to the control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other airborne pathogens: A UK hospital based pilot study. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2000, 94, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, F.M. Relative susceptibility of acid-fast and non-acid-fast bacteria to ultraviolet light. Appl. Microbiol. 1971, 21, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.R.; Knibbs, L.D.; Kidd, T.J.; Wainwright, C.E.; Wood, M.E.; Ramsay, K.A.; Bell, S.C.; Morawska, L. A Novel Method and Its Application to Measuring Pathogen Decay in Bioaerosols from Patients with Respiratory Disease. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sónia Gonçalves Pereira, I.P.M.; Ana Cristina Rosa and Olga Cardoso. Susceptibility to ultraviolet light C of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms from hydropathic respiratory treatment equipments: Impact in water quality control and public health. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2015, 4, 1200–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, A.A. New sampler for the collection, sizing, and enumeration of viable airborne particles. J. Bacteriol. 1958, 76, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macher, J.M. Positive-hole correction of multiple-jet impactors for collecting viable microorganisms. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 1989, 50, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- First, M.; Rudnick, S.N.; Banahan, K.F.; Vincent, R.L.; Brickner, P.W. Fundamental factors affecting upper-room ultraviolet germicidal irradiation—part I. Experimental. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2007, 4, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, G.; First, M.W.; Burge, H.A. The characterization of upper-room ultraviolet germicidal irradiation in inactivating airbone microorganisms. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickner, P.W.; Vincent, R.L.; First, M.; Nardell, E.; Murray, M.; Kaufman, W. The application of ultraviolet germicidal irradiation to control transmission of airborne disease: Bioterrorism countermeasure. Public Health Rep. 2003, 118, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First MW, N.E.; Chaisson, W.; Riley, R. Guidelines for the application of upper-room ultraviolet germicidal irradiation for preventing transmission of airborne contagion-Part I: Basic principles. Trans. Am. Soc. Heat. Refrig. Air Cond. Eng. 1999, 105, 869–876. [Google Scholar]

- Knibbs, L.D.; Morawska, L.; Bell, S.C.; Grzybowski, P. Room ventilation and the risk of airborne infection transmission in 3 health care settings within a large teaching hospital. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2011, 39, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardell, E.A.; Bucher, S.J.; Brickner, P.W.; Wang, C.; Vincent, R.L.; Becan-McBride, K.; James, M.A.; Michael, M.; Wright, J.D. Safety of upper-room ultraviolet germicidal air disinfection for room occupants: Results from the Tuberculosis Ultraviolet Shelter Study. Public Health Rep. 2008, 123, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardell, E.; Vincent, R.; Sliney, D.H. Upper-room ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI) for air disinfection: A symposium in print. Photochem. Photobiol. 2013, 89, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIOSH. Environmental Control for Tuberculosis: Basic Upper-Room Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation Guidelines for Healthcare Settings; DHHS (NIOSH): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2009. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2009-105/pdfs/2009-105.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Agency ARPaNS. Radiation Protection Series No. 12. In Radiation Protection Standard, Occupational Exposure to Ultraviolet Radiation; Agency ARPaNS: Yallambie, Australia, 2006. Available online: https://www.arpansa.gov.au/sites/default/files/legacy/pubs/rps/rps12.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Bergman, R.S. Germicidal UV Sources and Systems(dagger). Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, S.E.; Wright, H.B.; Hargy, T.M.; Larason, T.C.; Linden, K.G. Action spectra for validation of pathogen disinfection in medium-pressure ultraviolet (UV) systems. Water Res. 2015, 70, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, D.K.; Kang, D.H. Using UVC Light-Emitting Diodes at Wavelengths of 266 to 279 Nanometers To Inactivate Foodborne Pathogens and Pasteurize Sliced Cheese. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2016, 82, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.Z.; Craik, S.A.; Bolton, J.R. Comparison of the action spectra and relative DNA absorbance spectra of microorganisms: Information important for the determination of germicidal fluence (UV dose) in an ultraviolet disinfection of water. Water Res. 2009, 43, 5087–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.W. The effect of environmental parameters on the survival of airborne infectious agents. J. R Soc. Interface 2009, 6 (Suppl. S6), S737–S746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.Y.; Li, C.S. Control effectiveness of ultraviolet germicidal irradiation on bioaerosols. Aerosol. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.W.; Weker, R.A.; Yasui, S.; Nardell, E.A. Monitoring human exposures to upper-room germicidal ultraviolet irradiation. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2005, 2, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifton, I.J.; Fletcher, L.A.; Beggs, C.B.; Denton, M.; Peckham, D.G. A laminar flow model of aerosol survival of epidemic and non-epidemic strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from people with cystic fibrosis. BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.M.; Brosseau, L.M. Aerosol transmission of infectious disease. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 57, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, R.; Cravigan, L.T.; Niazi, S.; Ristovski, Z.; Johnson, G.R. In situ measurements of human cough aerosol hygroscopicity. J. R. Soc. Interface 2021, 18, 20210209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, S.; Groth, R.; Cravigan, L.; He, C.R.; Tang, J.W.; Spann, K.; Johnson, G.R. Susceptibility of an Airborne Common Cold Virus to Relative Humidity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| UV-C Dose (µW s/cm2) | Total n = 34 | UV-C Effectiveness (%, SD) | Equivalent Air Exchange Rate due to UV-C (eAER, SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 * | 8 | 55.2 (4.4) § | 2.2 (0.2) † |

| 62 | 3 | 4.5 (6.1) | 0.1 (0.1) |

| 123 | 4 | 24.6 (6.1) | 0.7 (0.2) |

| 246 | 4 | 50.9 (5.1) | 2.3 (0.3) |

| 492 | 4 | 68.6 (2.1) | 4.5 (0.8) |

| 984 | 4 | 82.5 (1.4) | 10.0 (1.7) |

| 1968 | 4 | 88.5 (2.0) | 15.8 (1.1) |

| 4920 | 3 | 87.5 (1.6) | 15.6 (0.8) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, T.T.; He, C.; Carter, R.; Ballard, E.L.; Smith, K.; Groth, R.; Jaatinen, E.; Kidd, T.J.; Nguyen, T.-K.; Stockwell, R.E.; et al. The Effectiveness of Ultraviolet-C (UV-C) Irradiation on the Viability of Airborne Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13706. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013706

Nguyen TT, He C, Carter R, Ballard EL, Smith K, Groth R, Jaatinen E, Kidd TJ, Nguyen T-K, Stockwell RE, et al. The Effectiveness of Ultraviolet-C (UV-C) Irradiation on the Viability of Airborne Pseudomonas aeruginosa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13706. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013706

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Thi Tham, Congrong He, Robyn Carter, Emma L. Ballard, Kim Smith, Robert Groth, Esa Jaatinen, Timothy J. Kidd, Thuy-Khanh Nguyen, Rebecca E. Stockwell, and et al. 2022. "The Effectiveness of Ultraviolet-C (UV-C) Irradiation on the Viability of Airborne Pseudomonas aeruginosa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13706. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013706

APA StyleNguyen, T. T., He, C., Carter, R., Ballard, E. L., Smith, K., Groth, R., Jaatinen, E., Kidd, T. J., Nguyen, T.-K., Stockwell, R. E., Tay, G., Johnson, G. R., Bell, S. C., & Knibbs, L. D. (2022). The Effectiveness of Ultraviolet-C (UV-C) Irradiation on the Viability of Airborne Pseudomonas aeruginosa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13706. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013706