Differences in and Factors Related to Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 in Long-Term Care Facilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

3. Results

3.1. Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with COVID-19 in Different Scenarios

3.2. Univariate Analysis of Factors Related to Willingness to Provide Care

3.3. Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Related to Willingness to Provide Care

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences in Personnel’s Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with COVID-19

4.2. Experience with Communicable Disease Control on Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with COVID-19

4.3. Effects of Various Work Incentives on Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with COVID-19

4.4. Relationships between Demographic Variables and Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with COVID-19

4.5. Analysis of Factors Related to Personnel’s Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with COVID-19

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Childs, A.; Zullo, A.R.; Joyce, N.R.; McConeghy, K.W.; van Aalst, R.; Moyo, P.; Bosco, E.; Mor, V.; Gravenstein, S. The burden of respiratory infections among older adults in long-term care: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECDC Public Health Emergency Team; Danis, K.; Fonteneau, L.; Georges, S.; Daniau, C.; Bernard-Stoecklin, S.; Domegan, L.; O’Donnell, J.; Hauge, S.H.; Dequeker, S.; et al. High impact of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities, suggestion for monitoring in the EU/EEA, May 2020. Euro Surveill 2020, 25, 2000956. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, M.; Searle, S.D.; McElhaney, J.E.; McNeil, S.A.; Clarke, B.; Rockwood, K.; Kelvin, D.J. COVID-19, frailty and long-term care: Implications for policy and practice. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Surveillance of COVID-19 at Long-Term Care Facilities in the EU/EEA; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/surveillance-COVID-19-long-term-care-facilities-EU-EEA (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Sun, N.; Wei, L.; Shi, S.; Jiao, D.; Song, R.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; You, Y.; et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 48, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, M.; Tang, F.; Wang, Y.; Nie, H.; Zhang, L.; You, G. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Henan, China. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, M.-C.; Wu, H.-C.; Lin, H.-T.; Lei, L.; Chao, C.-L.; Lu, C.-M.; Yang, W.-P. Exploring the stress, psychological distress, and stress-relief strategies of Taiwan nursing staffs facing the global outbreak of COVID-19. J. Nurs. 2020, 67, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- White, E.M.; Wetle, T.F.; Reddy, A.; Baier, R.R. Front-line Nursing Home Staff Experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahed, W.Y.A.; Hefzy, E.M.; Ahmed, M.I.; Hamed, N.S. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perception of Health Care Workers Regarding COVID-19, A Cross-Sectional Study from Egypt. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshutwi, S.S. ‘Senior Nursing Students and Interns’ Concerns and Willingness to Treat Patients with COVID-19: A Strategy to Expand National Nursing Workforce during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Risk Manag. Health Policy 2021, 14, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Long-Term Care Services Act. 2021. Available online: https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=L0070040 (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Chen, S.J. The Study of University Social-Welfare and Social-Work Department Students’ Attitude and Behavior Intention to the Aged. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Social Welfare, Hsuan Chuang University, Hsinchu City, Taiwan, 2006. Available online: https://ndltd.ncl.edu.tw/cgi-bin/gs32/gsweb.cgi/login?o=dnclcdr&s=id=%22094HCU00206002%22.&searchmode=basic (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Dykgraaf, S.H.; Matenge, S.; Desborough, J.; Sturgiss, E.; Dut, G.; Roberts, L.; McMillan, A.; Kidd, M. Protecting Nursing Homes and Long-Term Care Facilities From COVID-19: A Rapid Review of International Evidence. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1969–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Number of Workers in Elderly Long Term Care, Nursing and Caring Institutions. 2021. Available online: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/dos/cp-5223-62358-113.html#_4.%E9%95%B7%E6%9C%9F%E7%85%A7%E9%A1%A7 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Raosoft Inc. Sample Size Calculator. 2004. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Crucial Policies for Combating COVID-19: Central Command Center for COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://covid19.mohw.gov.tw/ch/cp-4825-53646-205.html (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Arcadi, P.; Simonetti, V.; Ambrosca, R.; Cicolini, G.; Simeone, S.; Pucciarelli, G.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E.; Durante, A. Nursing during the COVID-19 outbreak: A phenomenological study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardebili, M.E.; Naserbakht, M.; Bernstein, C.; Alazmani-Noodeh, F.; Hakimi, H.; Ranjbar, H. Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, D.; Haase, J.E.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.Q.; Liu, S.; Xia, L.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, B.X. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: A qualitative study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e790–e798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyashanu, M.; Pfende, F.; Ekpenyong, M. Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK. J. Interprofessional Care 2020, 34, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Madrazo, J.A.; Sosa-Tinoco, E.; Flores-Castro, M.; López-Ortega, M.; Gutiérrez-Robledo, L.M. COVID-19 and long-term care facilities in Mexico: A debt that cannot be postponed. Gac. Med. Mex. 2021, 157, 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mcphee, M. Valuing Patient Safety: Responsible Work-Force Design. 2014. Available online: https://nursesunions.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Valuing-Patient-Safety-PRINT-May-2014.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Chaaban, T.; Ahouah, M.; Lombrail, P.; Morvillers, J.M.; Rothan-Tondeur, M.; Carroll, K. Nursing role for medication stewardship within long-term care facilities. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2019, 32, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Hashimoto, K.; Zhang, K.; Liu, H. Knowledge and attitudes of medical staff in Chinese psychiatric hospitals regarding COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 4, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guan, X.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Tong, Y.; Ren, R.; Leung, K.S.M.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Wong, J.Y.; et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, C.; Schunk, M.; Sothmann, P.; Bretzel, G.; Froeschl, G.; Wallrauch, C.; Zimmer, T.; Thiel, V.; Janke, C.; Guggemos, W.; et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 970–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, D.D.; Dick, A.; Agarwal, M.; Jones, K.M.; Mody, L.; Stone, P.W. COVID-19 Preparedness in Nursing Homes in the Midst of the Pandemic. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1164–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T.M. Personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A reply. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 1121–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, E.; Cárdenas, L.; Kieffer, E.; Larson, E. Reflections from the "Forgotten Front Line": A qualitative study of factors affecting wellbeing among long-term care workers in New York City during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ET Today News. Far Eastern Memorial Hospital Enlists Recovered Patients to Take Care of Confirmed Patients. 2022. Available online: https://today.line.me/tw/v2/article/Gg3WgQY (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- El-Hage, W.; Hingray, C.; Lemogne, C.; Yrondi, A.; Brunault, P.; Bienvenu, T.; Etain, B.; Paquet, C.; Gohier, B.; Bennabi, D.; et al. Health professionals facing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: What are the mental health risks? Encephale 2020, 46, S73–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, C.; Yang, B.X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Lai, J.; Ma, X.; et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brereton, A.I. Toward a Preliminary Theory of Organizational Incentives: Addressing Incentive Misalignment in Private Equity-Owned Long-Term Care Facilities. Am. J. Law Med. 2021, 47, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.D. Nurses’ ability and willingness to work during pandemic flu. J. Nurs. Manag. 2011, 19, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanios, A.; Bocheńska-Brandt, A. Occupational burnout among workers in the long-term care sector in relation to their personality traits. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2021, 34, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyagi, Y.; Beck, C.R.; Dingwall, R.; Nguyen-Van-Tam, J.S. Healthcare workers’ willingness to work during an influenza pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Influ. Other Respir. Viruses 2015, 9, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Willing to Provide Care | Unwilling to Provide Care | No Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Willingness to provide care to patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 | 119 (30.9) | 156 (40.5) | 110 (28.6) |

| 1. Reasons for willingness to provide care (multiple choice) | |||

| 1.1. Responsibility as a professional | 87 (33.2) | ||

| 1.2. Opportunities for personal learning and growth | 76 (29.0) | ||

| 1.3. Performance of job duties | 70 (26.7) | ||

| 1.4. Previous experience with caring for patients with COVID-19 | 13 (5.0) | ||

| 1.5. Completion of training or courses related to caring for patients with COVID-19 | 13 (5.0) | ||

| 1.6. Others | 3 (1.1) | ||

| 2. Reasons for unwillingness to provide care (multiple choice) | |||

| 2.1. Not considering taking care of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 to be an institutional responsibility | 31 (9.3) | ||

| 2.2. Lack of relevant expertise | 98 (29.4) | ||

| 2.3. Reluctance to risk exposure to the virus | 82 (24.6) | ||

| 2.4. Insufficient care equipment and human resources at the institution | 65 (19.5) | ||

| 2.5. Lack of proper PPE | 37 (11.1) | ||

| 2.6. Others | 20 (6.0) | ||

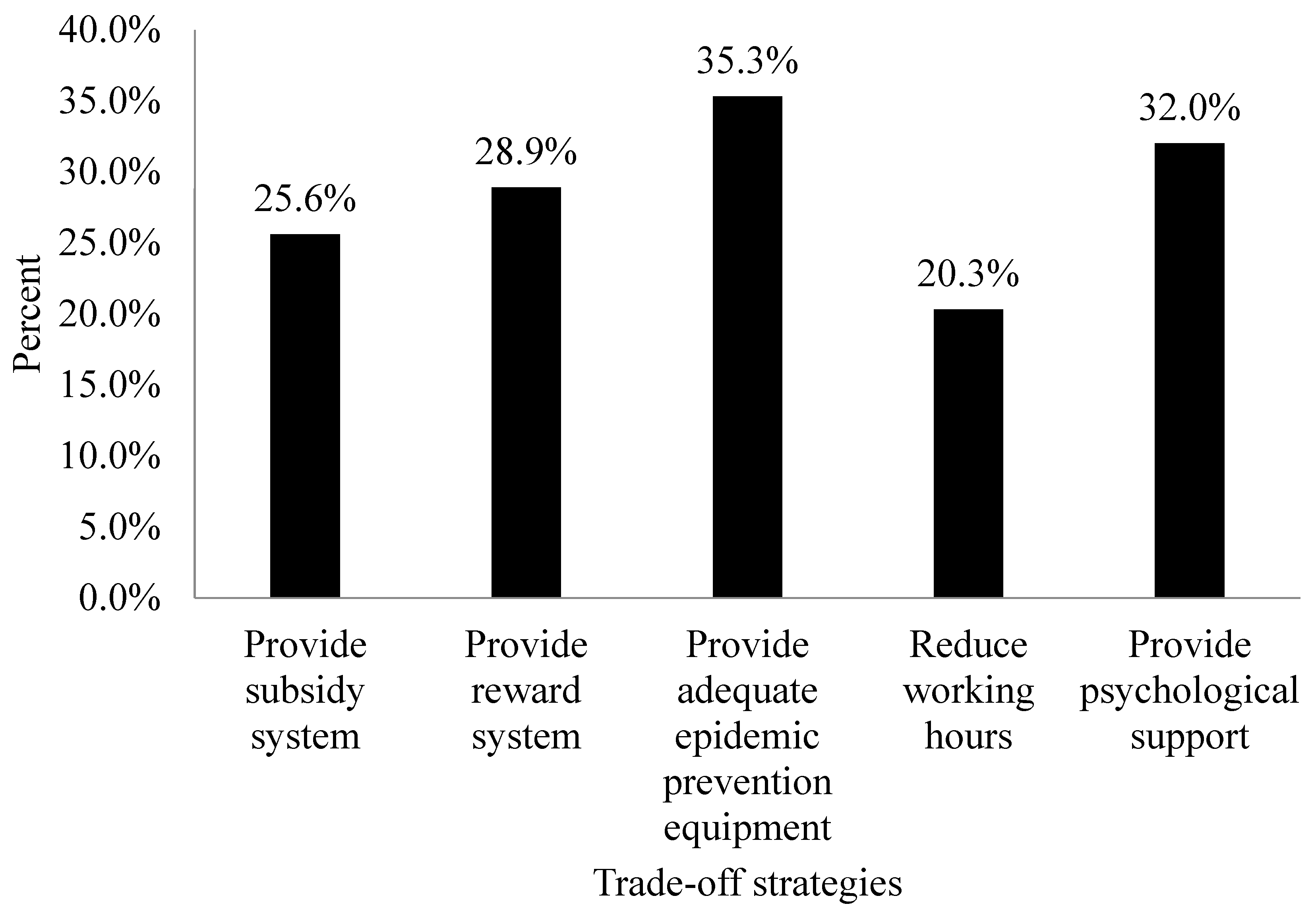

| 3. Trade-off conditions (incentives offered by institutions; n = 266) | |||

| 3.1. Subsidy systems (e.g., subsidies related to contracting COVID-19 at work) | 68 (25.5) | 93 (35.0) | 105 (39.5) |

| 3.2. Incentive systems (e.g., epidemic prevention bonuses and care bonuses) | 77 (28.9) | 94 (35.3) | 95 (35.7) |

| 3.3. Sufficient PPE | 94 (35.4) | 90 (33.8) | 82 (30.8) |

| 3.4. Reductions in working hours | 54 (20.3) | 126 (47.4) | 86 (32.3) |

| 3.5. Mental health support programs | 85 (32.0) | 101 (38.0) | 80 (30.0) |

| Variable | Willingness to Provide Care | χ² | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing to Provide Care (%) | Unwilling to Provide Care (%) | |||

| Gender | 1.50 | 0.221 | ||

| Male | 21 (36.2) | 37 (63.8) | ||

| Female | 98 (45.2) | 119 (54.8) | ||

| Age (years) | 5.83 | 0.121 | ||

| 20–35 | 6 (25.0) | 18 (75) | ||

| 36–50 | 41 (41.4) | 58 (58.6) | ||

| 51–64 | 53 (49.1) | 55 (50.9) | ||

| ≥65 | 19 (43.2) | 25 (56.8) | ||

| Education level | 4.89 | 0.180 | ||

| Junior high school or below | 37 (59.7) | 25 (40.3) | ||

| Senior high school | 61 (73.5) | 22 (26.5) | ||

| Junior college or above | 168 (70.0) | 72 (30.0) | ||

| Marital status | 0.29 | 0.589 | ||

| Unmarried, divorced, or widowed | 39 (41.1) | 56 (58.9) | ||

| Married | 80 (44.4) | 100 (55.6) | ||

| Religious belief | 2.98 | 0.394 | ||

| None | 43 (40.6) | 63 (59.4) | ||

| Buddhist | 34 (41.0) | 49 (59.0) | ||

| Christian | 13 (40.6) | 19 (59.4) | ||

| Others * | 29 (53.7) | 25 (46.3) | ||

| Breadwinner | 0.078 | 0.780 | ||

| Yes | 60 (44.1) | 76 (55.9) | ||

| No | 59 (42.4) | 80 (57.6) | ||

| Self-rated health | ||||

| Healthy | 70 (43.2) | 92 (56.8) | 0.242 | 0.886 |

| Normal | 43 (42.6) | 58 (57.4) | ||

| Unhealthy | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | ||

| Variable | Willingness to Provide Care | χ² | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing to Provide Care (%) | Unwilling to Provide Care (%) | |||

| Total years of employment at current institution | 0.60 | 0.741 | ||

| 1–10 | 86 (42.0) | 119 (58.0) | ||

| 11–20 | 22 (47.8) | 24 (52.2) | ||

| >20 | 11 (45.8) | 13 (54.2) | ||

| Number of patients served daily | 2.17 | 0.537 | ||

| 1–10 | 37 (43.5) | 48 (56.5) | ||

| 11–15 | 11 (50.0) | 11 (50.0) | ||

| ≥16 | 44 (48.4) | 47 (51.6) | ||

| Uncountable | 27 (35.1) | 50 (64.9) | ||

| Service hours per month | 1.06 | 0.787 | ||

| 40–79 | 9 (34.6) | 17 (65.4) | ||

| 80–119 | 6 (40.0) | 9 (60.0) | ||

| 120–159 | 14 (46.7) | 16 (53.3) | ||

| ≥160 | 90 (44.1) | 114 (55.9) | ||

| Monthly income (USD) | 15.84 | <0.001 | ||

| <1000 | 10 (22.2) | 35 (77.8) | ||

| 1000–1500 | 75 (42.9) | 100 (57.1) | ||

| >1500 | 34 (61.8) | 21 (38.2) | ||

| Variable | Willingness to Provide Care | χ² | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing to Provide Care (%) | Unwilling to Provide Care (%) | |||

| Previous experience with caring for patients with suspected COVID-19 | 0.31 | 0.576 | ||

| Yes | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | ||

| No | 111 (42.9) | 148 (57.1) | ||

| Previous experience with caring for patients with confirmed COVID-19 | 3.54 | 0.060 | ||

| Yes | 10 (41.2) | 5 (58.8) | ||

| No | 109 (41.9) | 151 (58.1) | ||

| Vaccination | 2.64 | 0.104 | ||

| Yes | 117 (42.9) | 156 (57.1) | ||

| No | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Completion of training related to communicable disease control | 8.81 | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 85 (50.3) | 84 (49.7) | ||

| No | 34 (32.1) | 72 (67.9) | ||

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Age (≤35 years) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 36–50 years | 2.30 | 0.78–6.81 | 0.131 | 1.96 | 0.56–6.80 | 0.290 | 3.16 | 0.76–13.18 | 0.114 |

| 51–64 years | 3.42 | 1.09–10.78 | 0.036 | 3.40 | 0.91–12.68 | 0.068 | 5.61 | 1.25–25.23 | 0.025 |

| ≥65 years | 2.25 | 0.73–6.94 | 0.157 | 3.30 | 0.90–12.02 | 0.072 | 5.65 | 1.29–24.75 | 0.021 |

| Education level (ref: Junior high school or below) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Senior high school | 0.49 | 0.22–1.09 | 0.079 | 0.39 | 0.16–0.95 | 0.038 | 0.37 | 0.15–0.90 | 0.028 |

| Junior college and above | 0.80 | 0.40–1.61 | 0.536 | 0.44 | 0.17–1.14 | 0.092 | 0.37 | 0.14–0.89 | 0.046 |

| Job category (ref: Caregiver) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Nurse | 3.39 | 1.21–9.50 | 0.021 | 4.03 | 1.38–11.77 | 0.011 | |||

| Social worker | 0.72 | 0.17–3.06 | 0.652 | 1.23 | 0.27–5.64 | 0.787 | |||

| Others ** | 1.03 | 0.34–3.07 | 0.964 | 1.49 | 0.47–4.72 | 0.494 | |||

| Number of patients served daily (ref: 1–10) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 11–15 | 1.06 | 0.35–3.24 | 0.920 | 0.90 | 0.28–2.88 | 0.863 | |||

| ≥16 | 0.49 | 0.22–1.11 | 0.087 | 0.44 | 0.19–1.02 | 0.055 | |||

| Indirect service | 0.41 | 0.16–1.04 | 0.061 | 0.30 | 0.11–0.83 | 0.020 | |||

| Monthly income (ref: <1000 USD) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 1000–1500 | 2.20 | 0.83–5.83 | 0.112 | 2.22 | 0.81–6.09 | 0.120 | |||

| >1500 | 5.22 | 1.56–17.47 | 0.007 | 5.26 | 1.48–18.61 | 0.010 | |||

| Experience with caring for patients with confirmed COVID-19 (ref: No) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Yes | 9.93 | 1.11–89.07 | 0.040 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, J.-R.; Lin, L.-P.; Lin, J.-D. Differences in and Factors Related to Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 in Long-Term Care Facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013461

Yu J-R, Lin L-P, Lin J-D. Differences in and Factors Related to Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 in Long-Term Care Facilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013461

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Jia-Rong, Lan-Ping Lin, and Jin-Ding Lin. 2022. "Differences in and Factors Related to Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 in Long-Term Care Facilities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013461

APA StyleYu, J.-R., Lin, L.-P., & Lin, J.-D. (2022). Differences in and Factors Related to Willingness to Provide Care to Patients with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 in Long-Term Care Facilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013461