Exploring Mental Health and Holistic Healing through the Life Stories of Indigenous Youth Who Have Experienced Homelessness

Abstract

1. Introduction and Review of Literature

Indigenous homelessness is not defined as lacking a structure of habitation; rather, it is more fully described and understood through a composite lens of Indigenous worldviews. These include: individuals, families and communities isolated from their relationships to land, water, place, family, kin, each other, animals, cultures, languages and identities. Importantly, Indigenous people experiencing these kinds of homelessness cannot culturally, spiritually, emotionally or physically reconnect with their Indigeneity or lost relationships.

2. Theoretical Framing

3. Materials and Methods

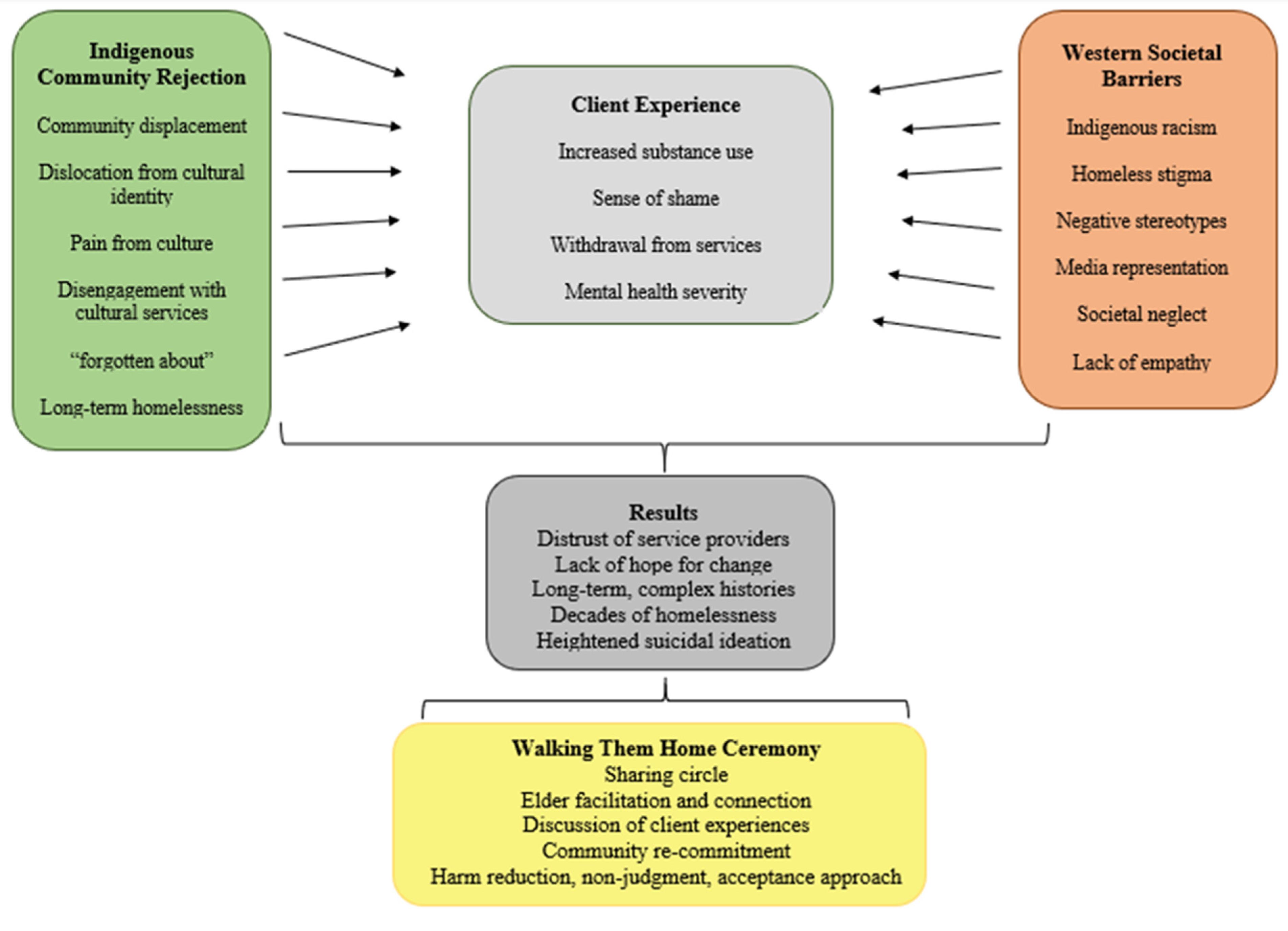

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Personal Domains of Health

4.1.1. Physical Health

I haven’t been on my medication in the longest … because I’ve been going from house to house, places like this, moved all around and my medication goes to one spot, oh he’s in a different town … we can’t give him any more meds because he has to go back to the city … they’re spending money from here to Newmarket to … 26 extra bucks for a bus ticket and then getting to Toronto and then walking how far in Toronto to get to wherever and then get my medication and then more money for a bus to get to Union Station, then from Union to wherever I will be staying and then to Newmarket and then uh Northern where I am…just in busses alone is like 75 bucks.(Daniel, age 26, Inuit youth)

4.1.2. Emotional Health

I was just drowning. I really felt like the whole world was against me. It just was not fair at all. I didn’t have—my family, they’re helpless to me. They’re in the same boat as me. There’s no one I could turn to. I don’t have a rich dad that could just pay my housing. What can I do to avoid becoming homeless?[5]

4.1.3. Spiritual Health

I think one of the reasons why we’re so successful at it is because we don’t insert protocol into ceremony. I couldn’t care less if you used last night, as long as your intention of going into that lodge is pure. And sincere. And that’s all that matters. You know, there’s too much imposed protocol on our people as it is from the settlers. We shouldn’t be doing it ourselves. Who cares that you’re wearing a pair of slacks into a ceremony area. Creator doesn’t care. Why should I care?[5]

... maybe they did abuse their partner; I don’t know. But that was yesterday; it’s not today. Who’s to say they’re going to do it today? So if I go in there with the attitude [of] if you’re a bad person because this is what you’re known to do, then they’re going to just walk out of there with a bad experience. Where we’ve really watched some of these men blossom, and they don’t know what they’re going to do when the program ends because they’ve gotten used to being accepted for who they are, being able to speak and not be judged for speaking”.[5]

And I think when society, especially in the city, gets back to that and funds safe spaces for people that are accepting of who they are and where they are in their journey. Because it’s your journey. It’s not my journey; it’s your journey. And you’re going to trip and fall and make the mistakes that you need to make to get you to a better place, get you where you need to be going. People need to fall and learn to pick themselves back up. But these people like all of us in the corner are supporting them.[5]

4.1.4. Mental Health

Everyone that is going through that same situation is going through the same things: depression, anxiety, any type of different mental health disorder … whatever it is, they’re going through that together… this is not something that we can necessarily control. You need to be able to control the way that you think about how we got there and why we’re here in this situation.[5]

If there’s some way where there’s an intervening process where you can help that person fight their battle with depression and anxiety, then they will be able to focus more on work or housing. If you have a scattered mind, or someone who’s depressed and doesn’t want to get up or do anything, you can’t expect that person to get up and do things. They’re just literally uncapable of doing that. It’s not even their fault. A lot of people are left fighting these battles alone, and then they’re left on the street and hooked up to drugs and needles because they couldn’t get out of that depression. Or that anxiety led them to think suicidal thoughts or something like that. Where do we step in?[5]

4.1.5. Suicidality, Self-Worth and Long-Term Effects

It was self-harm depression and suicidal … first like, with the depression, it wasn’t for like, it was to make myself feel pain, I would bash my head on stuff, anything, just so I wouldn’t feel emotional and then I wouldn’t start feeling that pain anymore so I just … I would just bash body parts and then it got to the point where I wouldn’t feel it, so I started cutting and at first, I was deathly afraid because I didn’t want to die when I first started doing it but I also didn’t want to feel the pain so it was challenging and then a year after I started cutting, I started attempting suicide, which seems to always fail, thank God, obviously, because I’m here.(Craig, age 23, Indigenous youth)

4.1.6. Substance Use

Ahh, it started off with weed and shrooms primarily, then uh meth, coke, which was not fun … We had guys that would come in with heroin … But you know, we did all this shit because we felt like, in a way, nobody cared because it’s like society had forgotten about us and everyone else that we had known had moved on and they don’t want to accept that this way of life exists … so it’s kind of like, that was another thing for us, was the hopelessness that developed from not really having any life skills…(James, age 24, Indigenous youth)

4.2. Social and Cultural Domains

4.2.1. Substance Use and Cultural Barriers

4.2.2. Health, Home and Education

4.2.3. Services

It was very hard trying to get the necessary help that I needed, because I didn’t know where to start. I had no resources; I had no help; I had no workers; I had nothing. No one. I had to really do a lot of independent research on my own, even though I wasn’t in shelter. They’re supposed to be doing all the helping and they’re supposed to, get me back on track and to avoid homelessness—because I’ve never been homeless before—to intervene before it’s something that continues to happen. Because I’m not stable; I don’t have the things that I should have at my age. So, if I wouldn’t have really took it upon myself to get the right help that I needed, I probably would have ended up staying in the shelter longer than I should have.[5] p. 457.

All she kept saying is, ‘housing is a 14-years-long waiting list, I can’t see you getting housing or your children back.’ She’s supposed to be someone who’s supporting families? No. That was really wrong and I actually, I told her about herself. I told her, ‘you automatically judged me. Your job is supposed to be non-biased. You’re not supposed to just stand there and judge people because of a little picture of what you have’.[5] p. 467.

It’s not because of us; it’s this economy and the way that everything is and how rigged this system is. It’s not fair for a lot of people, especially the people that are living in poverty. It just never ends well for us. So we really need somebody to give these women a chance to just become successful. Don’t we all have that right? I think about that all the time.[5] p. 471.

4.2.4. Racism

I don’t feel like they should have workers that are not Native because most of the referrals that they get are Native parents. How can you send someone who won’t understand their point of view? I automatically become biased, because they don’t understand what that person has gone through to get where they are, what happened for them to be where they are. … We get discriminated on a daily basis. I’m not only Native but I’m a Black woman too. So, when do we get a break?[5] p. 468.

…there was a guy in a wheelchair that was sitting like this for quite a while. How hard was it for me to tap him on the shoulder and say, dude, are you OK? And he acknowledged us and off we went. He wasn’t asking for anything; he just fell asleep. What if he was dead there? People don’t give a s---. But if it was a dog or a squirrel or a raccoon lying on the side of the street, people would be all over it.[5]

5. Discussion and Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, T. Chapter 4: Indigenous Youth in Canada. Portrait of Youth in Canada: Data report, Statistics Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/42-28-0001/2021001/article/00004-eng.htm (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Statistics Canada. Statistics on Indigenous Peoples. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Patrick, C. Aboriginal Homelessness in Canada: A Literature Review; Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, S. Supporting Indigenous youth experiencing homelessness. In Mental Health and Addiction Interventions for Youth Experiencing Homelessness: Practical Strategies for Front-Line Providers; Kidd, S., Slesnick, N., Frederick, T., Karabanow, J., Gaetz, S., Eds.; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, M.D. Employment and Education Pathways: Exploring Traditional Knowledges Supports for Transitions Out of Homelessness for Indigenous Peoples. Published Doctoral Dissertation; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Memmott, P.; Chambers, C. Indigenous Homelessness in Australia: An Introduction. Parity 2010, 23, 8–11. Available online: http://homelesshub.ca/resource/indigenous-homelessness-australia-introduction (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Newhouse, D. Reconciliation. Indigenous Studies: David Newhouse. Trent University. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WIP966KOsps (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Cannon, M.; Sunseri, L. Racism, Colonialism and Indigeneity in Canada: A Reader; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhard, A. Reconciliation or racialization? Contemporary discourses about residential schools in the Canadian Prairies. Can. J. Educ. 2017, 40, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tasker, J. Residential Schools Findings Point to “Cultural Genocide,” Commission Chair Says. CBC News. Available online: http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/residential-schools-findings-point-tocultural-genocide-commission-chair-says-1.3093580 (accessed on 29 May 2015).

- Canadian Observatory on Homelessness. Definition of Youth Homelessness. Available online: https://www.homelesshub.ca/resource/canadian-definition-youth-homelessness (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Thistle, J. Indigenous Definition of Homelessness in Canada; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aboriginal Standing Committee on Housing and Homelessness (ASCHH). Plan to End Aboriginal Homelessness in Calgary; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- La Gory, M.; Ritchey, F.J.; Mullis, J. Depression among the homeless. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1990, 31, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.A.; Saxe, L.; Harvey, M. Homelessness as psychological trauma: Broadening perspectives. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.L.; Rezansoff, S.; Currie, L.; Somers, J.M. Trajectories of recovery among homeless adults with mental illness who participated in a randomised controlled trial of Housing First: A longitudinal, narrative analysis. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, M.D. Our Home Is Native Land: Teachings, Perspectives, & Experiences of Indigenous Houselessness. J. Nonprofit Soc. Econ. Res. 2022. submitted. Decolonizing Inequities: Indigenous self-sustenance in a social economy, special issue. [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan, C. Poverty, Indigeneity and the Socio-Legal Adjudication of Self Sufficiency. Critical Legal Thinking: Law and the Political. Available online: http://criticallegalthinking.com/2017/07/25/poverty-indigeneity-socio-legal-adjudication-self-sufficiency/ (accessed on 25 July 2017).

- Kidd, S.; Slesnick, N.; Frederick, T.; Karabanow, J.; Gaetz, S. Mental Health and Addiction Interventions for Youth Experiencing Homelessness: Practical Strategies for Front-Line Providers; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, C. Shared Stories, Silent Understandings Aboriginal Women Speak on Homelessness. Master’s Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, NF, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carl, H. Greater Vancouver Regional Steering Committee on Homelessness (Hrsg.): Results of the 2014 Homeless Count in the Metro Vancouver Region; Socialnet.de/Rezensionen für die Sozialwirtschaft: Eichstätt, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Christiensen, J. Homeless in a Homeland: Housing (in)Security and Homelessness in Inuvik and Yellowknife, Northwest Territories. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Christiensen, J. ‘They want a different life’: Rural northern settlement dynamics and pathways to homelessness in Yellowknife and Inuvik, Northwest Territories. Can. Geogr. 2012, 56, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetz, S.; O’Grady, B.; Kidd, S.; Schwan, K. Without a Home: The National Youth Homelessness Survey; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thistle, J. Defining Indigenous Homelessness: “Listen and They Will Tell You”; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Belanger, Y.D.; Head, G.W.; Awosoga, O. Housing and Aboriginal People in Urban Centres: A Quantitative Evaluation. Aborig. Policy Stud. 1969, 2, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, Y.D.; Weasel Head, G. Homelessness, Urban Aboriginal people and the need for a national enumeration. Aborig. Policy Stud. 2013, 2, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwan, K.; French, D.; Gaetz, S.; Ward, A.; Akerman, J.; Redman, M. Preventing youth homelessness: An international review of evidence. Public Policy Inst. Wales 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.A.; Cobb-Richardson, P.; Connolly, A.J.; Bujosa, C.T.; O’Neall, T.W. Substance abuse and personality disorders in homeless drop-in center clients: Symptom severity and psychotherapy retention in a randomized clinical trial. Compr. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassuk, E.L.; Browne, A.; Buckner, J.C. Families living in poverty. Sci. Am. 1996, 275, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, C.L.M.; Dominguez, B.; Schanzer, B.; Hasin, D.S.; Shrout, P.E.; Felix, A.; McQuistion, H.; Opler, L.A.; Hsu, E. Risk Factors for Long-Term Homelessness: Findings From a Longitudinal Study of First-Time Homeless Single Adults. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 1753–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, D.B.; Susser, E.S.; Struening, E.L.; Link, B.L. Adverse childhood experiences: Are they risk factors for adult homelessness? Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padgett, D.K.; Struening, E.L. Victimization and traumatic injuries among the homeless: Associations with alcohol, drug, and mental problems. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1992, 62, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rog, D.J.; Holupka, C.S.; McCombs-Thornton, K.L. Implementation of the Homeless Families Program: 1. Service models and preliminary outcomes. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1995, 65, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Whitbeck, L.B.; Bales, A. Life on the Streets: Victimization and Psychological Distress Among the Adult Homeless. J. Interpers. Violence 1989, 4, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.A.; Gelberg, L. Homeless men and women: Differential associations among substance abuse, psychosocial factors, and severity of homelessness. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1995, 3, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, S. Exploring Schooling and Educational Attainment through the Experiences of Homeless Youth. Unpublished. Doctoral Dissertation, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz, S.; Redman, M. Federal Investment in Youth Homelessness: Comparing Canada and the United States and a Proposal for Reinvestment; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Policy Brief, The Homeless Hub Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy Directives. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/homelessness.html (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Absolon, K.E. Indigenous holistic theory: A knowledge set for practice. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2010, 5, 74–87. Available online: https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/online-journal/vol5num/Absolon_pp74.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- First Nations Centre. OCAP®: Ownership, Control, Access and Possession. In Sanctioned by the First Nations Information Governance Committee, Assembly of First Nations; National Aboriginal Health Organization: Ottawa, OT, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hirtle, J.S.P. Social constructivism. Engl. J. 1996, 85, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolson, M.S. By Sleight of Neoliberal Logics: Street Youth, Workfare, and the Everyday Tactics of Survival in London, Ontario, ON, Canada. City Soc. 2015, 27, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetz, S.; O’ Grady, B. Why don’t you just get a job? Homeless youth, social exclusion and employment training. In Youth Homelessness in Canada: Implications for Policy and Practice; Gaetz, S., O’ Grady, B., Buccieri, K., Karabanow, J., Marsolais, A., Eds.; Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Karabanow, J.; Carson, A.; Clement, P. Leaving the Streets: Stories of Canadian Youth; Fernwood Basics Series: Halifax, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klodawsky, F.; Aubry, T.; Farrell, S. Care and the Lives of Homeless Youth in Neoliberal Times in Canada. Gender Place Cult. 2006, 13, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, P. Social exclusion and citizenship in a global society. Youth Policy 2003, 80, 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, S. Young homeless people and social exclusion. Youth Policy 1998, 59, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. Social Exclusion, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, S.; Aubry, T.; Klodawsky, F. Resilient Educational Outcomes: Participation in School by Youth With Histories of Homelessness. Youth Soc. 2010, 43, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, R. Youth, the “Underclass” and Social Exclusion; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, R.; Marsh, J. Disconnected youth? J. Youth Stud. 2001, 4, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.; Crawley, J.; Kane, D. Social exclusion, health and hidden homelessness. Public Health. 2016, 139, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, J. Social Exclusion, Gender, and Access to Education in Canada: Narrative Accounts from Girls on the Street. Fem. Form. 2011, 23, 110–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetz, S.; Schwan, K.; Redman, M.; French, D.; Dej, E. The Roadmap for the Prevention of Youth Homelessness; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mandianipour, A. Social exclusion and space. In Social Exclusion in European Cities; Mandianipour, A., Cars, G., Allen, J., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 1998; pp. 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, D. Social exclusion: A philosophical anthropology. Politics 2007, 25, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.L. Promoting Indigenous mental health: Cultural perspectives on healing from Native counsellors in Canada. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2008, 46, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J. Qualitative Researching; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson/Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, A.; Donaldson, J.; Gaetz, S.A.; Mirza, S.; Coplan, I.; Fleischer, D. Leaving Home: Youth Homelessness in York Region; The Homeless Hub Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- National Learning Community on Youth Homelessness. Available online: http://learningcommunity.ca/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Kidd, S. Mental health and youth homelessness: A critical review. In Youth Homelessness in Canada: Implications for Policy and Practice; Gaetz, S., O’Grady, B., Buccieri, K., Karabnow, J., Marsolais, A., Eds.; Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013; pp. 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Toolis, E.E.; Hammack, P.L. The lived experience of homeless youth: A narrative approach. Qual. Psychol. 2015, 2, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, S.A.; Gaetz, S.; O’Grady, B. The 2015 National Canadian Homeless Youth Survey: Mental Health and Addiction Findings. Can. J. Psychiatry 2017, 62, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, A.; Howes, C. Responding to mental health concerns on the front line: Building capacity at a crisis shelter for youth experiencing homelessness. In Mental Health and Addiction Interventions for Youth Experiencing Homelessness: Practical Strategies for Front-Line Providers; Kidd, S., Slesnick, N., Frederick, T., Karabanow, J., Gaetz, S., Eds.; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McCay, E.; Aiello, A. Dialectical behaviour therapy to enhance emotional regulation & resilience among street-involved youth. In Mental Health and Addiction Interventions for Youth Experiencing Homelessness: Practical Strategies for Front-Line Providers; Kidd, S., Slesnick, N., Frederick, T., Karabanow, J., Gaetz, S., Eds.; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, S.A.; Carroll, M.R. Coping and suicidality among homeless youth. J. Adolesc. 2007, 30, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, T.J.; Kirst, M.; Erickson, P.G. Suicide attempts and suicidal ideation among street-involved youth in Toronto. Adv. Ment. Health 2012, 11, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetz, S.; Donaldson, J.; Richter, T.; Gulliver, T. The State of Homelessness in Canada–2013; Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013; Available online: http://homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/SOHC2103.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Kidd, S.A. “The walls were closing in, and we were trapped”: A qualitative analysis of street youth suicide. Youth Soc. 2004, 36, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirst, M.; Frederick, T.; Erickson, P.G. Concurrent mental health and substance use problems among street-involved youth. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2011, 9, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.; Hagan, J. Surviving on the street: The experience of homeless youth. J. Adolesc. Res. 1992, 7, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetz, S.; O’Grady, B.; Buccieri, K. Surviving Crime and Violence: Street Youth Victimization in Toronto; Justice for Children and Youth & the Homeless Hub, Homeless Hub Research Report Series #1; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, A.J.; Steiman, M.; Cauce, A.M.; Cochran, B.N.; Whitbeck, L.B.; Hoyt, D.R. Victimization and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Homeless Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz-Rashid, S. Employment experiences of homeless young adults: Are they different for youth with a history of foster care? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2005, 28, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.R.; Allen, N.B. Trauma and homelessness in youth: Psychopathology and intervention. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 54, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, E.K.; Olivet, J.; Bassuk, E. Trauma-informed care for street involved youth. In Mental Health and Addiction Interventions for Youth Experiencing Homelessness: Practical Strategies for Front-Line Providers; Kidd, S., Slesnick, N., Frederick, T., Karabanow, J., Gaetz, S., Eds.; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Price, E. Laziness Does Not Exist, But Unseen Barriers Do. Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/@dr_eprice/laziness-does-not-exist-3af27e312d01 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Gabriel, M.D. Indigenous Homelessness and Traditional Knowledge: Stories of Elders and Outreach Support. Master’s Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, S.; Beaulieu, T.; Gabriel, M.D.; Elliott, N.; Hyatt, A.; Ayoub, M. Mental Health Interventions for Aboriginal Homelessness: Best Practices from the Streets. In Proceedings of the Workshop presented at 77th Canadian Psychology Association National Convention, Victoria, BC, Canada, 9 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, T.N.; Marsh, D.C.; Ozawagosh, J.; Ozawagosh, F.; Northern Ontario School of Medicine; Nation, A.A.F. The Sweat Lodge Ceremony: A Healing Intervention for Intergenerational Trauma and Substance Use. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, J.W.; Moore, K. The impact of sweat lodge ceremony on dimensions of well-being. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. J. Natl. Cent. 2006, 13, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwan, K.; Gaetz, S.; French, D.; Redman, M.; Thistle, J.; Dej, E. What Would It Take? Youth Across Canada Speak Out on Youth Homelessness Prevention; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Edidin, J.P.; Ganim, Z.; Hunter, S.J.; Karnik, N.S. The Mental and Physical Health of Homeless Youth: A Literature Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2011, 43, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klos, N. Aboriginal Peoples and Homelessness: Interviews with Service Providers. Can. J. Urban Res. 1997, 6, 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ommer, R.E. The Coasts Under Stress Research Project team. Coasts under stress. In Restructuring and Social Ecological Health; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Piliavin, I.; Wright, B.R.E.; Mare, R.D.; Westerfelt, A.H. Exits from and Returns to Homelessness. Soc. Serv. Rev. 1996, 70, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. Dealing Effectively with Aboriginal Homelessness in Toronto: Final Report; Jim Ward Associates: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.; Maxim, P.; Gyimah, S.O. Labour Force Activity of Women in Canada: A Comparative Analysis of Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Women. Can. Rev. Sociol. Can. de Sociol. 2008, 40, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, N. Youth, School, and Community: Participatory Institutional Ethnographies; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Montez, J.K.; Hummer, R.A.; Hayward, M.D. Educational Attainment and Adult Mortality in the United States: A Systematic Analysis of Functional Form. Demography 2012, 49, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S. Addressing Strengths and Disparities in Indigenous Health. Int. J. Indig. Health. 2020, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelke, N.D.; Wilfreda, E.; Thurston, W.; Turner, D. Aboriginal Homelessness: A Framework for Best Practice in the Context of Structural Violence. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2016, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.; Gaetz, S. The Upstream Project Canada: An Early Intervention Strategy to Prevent Youth Homelessness & School Disengagement; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gabriel, M.D.; Mirza, S.; Stewart, S.L. Exploring Mental Health and Holistic Healing through the Life Stories of Indigenous Youth Who Have Experienced Homelessness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013402

Gabriel MD, Mirza S, Stewart SL. Exploring Mental Health and Holistic Healing through the Life Stories of Indigenous Youth Who Have Experienced Homelessness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013402

Chicago/Turabian StyleGabriel, Mikaela D., Sabina Mirza, and Suzanne L. Stewart. 2022. "Exploring Mental Health and Holistic Healing through the Life Stories of Indigenous Youth Who Have Experienced Homelessness" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013402

APA StyleGabriel, M. D., Mirza, S., & Stewart, S. L. (2022). Exploring Mental Health and Holistic Healing through the Life Stories of Indigenous Youth Who Have Experienced Homelessness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013402