Parenting Styles, Mental Health, and Catastrophizing in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Case-Control Study

Abstract

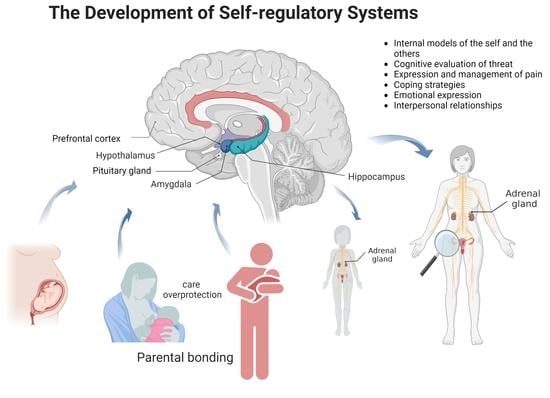

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Demographic Data

2.5.2. Assessment of Parental Bonding

2.5.3. Assessment of Anxiety

2.5.4. Assessment of Depression

2.5.5. Assessment of Pain Catastrophizing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethics

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahangari, A. Prevalence of chronic pelvic pain among women: An updated review. Pain Physician 2014, 17, E141–E147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, F.M. The role of laparoscopy in the chronic pelvic pain patient. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 46, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira-Campos, V.M.; Da Luz, R.A.; de Deus, J.M.; Zangiacomi Martinez, E.; Conde, D.M. Anxiety and depression in women with and without chronic pelvic pain: Prevalence and associated factors. J. Pain Res. 2019, 12, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripoli, T.M.; Sato, H.; Sartori, M.G.; De Araújo, F.F.; Girão, M.J.B.C.; Schor, E. Evaluation of quality of life and sexual satisfaction in women suffering from chronic pelvic pain with or without endometriosis. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnoaham, K.E.; Hummelshoj, L.; Webster, P.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Cicco Nardone, F.; De Cicco Nardone, C.; Jenkinson, C.; Kennedy, S.H.; Zondervan, K.T. Reprint of: Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: A multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, e137–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. RCOG Green-Top Guideline No. 41: The Initial Management of Chronic Pelvic Pain, 2nd ed.; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: London, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg41/ (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Siqueira-Campos, V.M.; de Deus, M.S.C.; Poli-Neto, O.B.; Rosa-E-Silva, J.C.; de Deus, J.M.; Conde, D.M. Current challenges in the management of chronic pelvic pain in women: From bench to bedside. Int. J. Womens Health 2022, 14, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). IASP Terminology. Available online: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/ (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Tarantino, S.; De Ranieri, C.; Dionisi, C.; Gagliardi, V.; Paniccia, M.F.; Capuano, A.; Frusciante, R.; Balestri, M.; Vigevano, F.; Gentile, S.; et al. Role of the attachment style in determining the association between headache features and psychological symptoms in migraine children and adolescentes: An analytical observational case-control study. Headache 2017, 57, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, N.R.; Lynch-Jordan, A.; Barnett, K.; Peugh, J.; Sil, S.; Goldschneider, K.; Kashikar-Zuck, S. Child pain catastrophizing mediates the relation between parent responses to pain and disability in youth with functional abdominal pain. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 59, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, E.; Zagoory-Sharon, O.; Feldman, R. Early maternal and paternal caregiving moderates the links between preschoolers’ reactivity and regulation and maturation of the HPA-immune axis. Dev. Psychobiol. 2021, 63, 1482–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundström, H.; Larsson, B.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Gerdle, B.; Kjølhede, P. Pain catastrophizing is associated with pain thresholds for heat, cold and pressure in women with chronic pelvic pain. Scand. J. Pain 2020, 20, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C.R.; Tuckett, R.P.; Song, C.W. Pain and stress in a systems perspective: Reciprocal neural, endocrine, and immune interaction. J. Pain 2008, 9, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoly, P. How pain shapes depression and anxiety: A hybrid self-regulatory/predictive mind perspective. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Setting 2021, 28, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisz, S.; Duschinsky, R.; Siegel, D.J. Disorganized attachment and defense: Exploring John Bowlby’s unpublished reflections. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2018, 20, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. II. Some principles of psychotherapy. The fiftieth Maudsley Lecture. Br. J. Psychiatry 1977, 130, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. Social engagement and attachment: A phylogenetic perspective. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 1008, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Allostasis and allostatic load: Implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology 2000, 22, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolacz, J.; Porges, S.W. Chronic diffuse pain and functional gastrointestinal disorders after traumatic stress: Pathophysiology through a polyvagal perspective. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schore, A.N. Effects of a secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant. Ment. Health J. 2003, 22, 7–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, T.J.; Jaaniste, T. Attachment and chronic pain in children and adolescents. Children 2016, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Tupling, H.; Brown, L.B. A Parental Bonding Instrument. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1979, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Bell, S.M.; Stayton, D.F. Infant-mother attachment and social development: Socialization as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In The Integration of a Child into a Social World; Richards, M.P.M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, M.; Ninomiya, T.; Anno, K.; Kawata, H.; Iwaki, R.; Sawamoto, R.; Kubo, C.; Kiyohara, Y.; Sudo, N.; Hosoi, M. Parenting style during childhood is associated with the development of chronic pain and a patient’s need for psychosomatic treatment in adulthood: A case-control study. Medicine 2020, 99, e21230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Failo, A.; Giannotti, M.; Venuti, P. Associations between attachment and pain: From infant to adolescente. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 2050312119877771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Moloney, C.; Seidman, L.C.; Zeltzer, L.K.; Tsao, J.C.I. Parental bonding in adolescents with and without chronic pain. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anno, K.; Shibata, M.; Ninomiya, T.; Iwaki, R.; Kawata, H.; Sawamoto, R.; Kubo, C.; Kiyohara, Y.; Sudo, N.; Hosoi, M. Paternal and maternal bonding styles in childhood are associated with the prevalence of chronic pain in a general adult population: The Hisayama Study. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avagianou, P.A.; Mouzas, O.D.; Siomos, K.E.; Zafiropoulou, M. The relationship of parental bonding to depression in patients with chronic pain. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2010, 9, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciechanowski, P.; Sullivan, M.; Jensen, M.; Romano, J.; Summers, H. The relationship of attachment style to depression, catastrophizing and health care utilization in patients with chronic pain. Pain 2003, 104, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, M.; Churilov, L.; Mooney, S.; Ma, T.; Maher, P.; Grover, S.R. Chronic pelvic pain—Pain catastrophizing, pelvic pain and quality of life. Scand. J. Pain. 2018, 18, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaire, C.; Williams, C.; Bodmer-Roy, S.; Zhu, S.; Arion, K.; Ambacher, K.; Wu, J.; Yosef, A.; Wong, F.; Noga, H.; et al. Chronic pelvic pain in an interdisciplinary setting: 1-year prospective cohort. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 114.e1–114.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantz, T.E.; Andrews, N.; Petersen, T.R.; Dunivan, G.C.; Montoya, M.; Swanson, N.; Wenzl, C.K.; Zambrano, J.R.; Komesu, Y.M. Adverse childhood experiences among gynecology patients with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, J.L.; Levin, B.; Paik, M.C. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leithner-Dziubas, K.; Bluml, V.; Nareder, A.; Tmej, A.; Fischer-Kern, M. Mentalization and bonding in chronic pelvic pain patients: A pilot study. Z. Psychosom. Med. Psychother. 2010, 56, 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, S.; Schestatsky, S.; Terra, L.; Knijnik, L.; Sanchez, P.; Ceitlin, L.H.F. Cross-cultural adaptation of Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) to Brazilian Portuguese. Rev. Psiquiatr. Rio Gd. Sul. 2006, 28, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.L.; Sousa, D.A.; Souza, A.M.F.L.P.; Manfro, G.G.; Salum, G.A.; Koller, S.H.; Osório, F.L.; Crippa, J.A.S. Factor structure, reliability, and item parameters of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the GAD-7 questionnaire. Trends Psychol. Temas Psicol. 2016, 24, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) Screeners. Available online: http://www.phqscreeners.com/ (accessed on 5 May 2018).

- Santos, I.S.; Tavares, B.F.; Munhoz, T.N.; Almeida, L.S.P.; Silva, N.T.B.; Tams, B.D.; Patella, A.M.; Matijasevich, A. Sensitivity and specificity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) among adults from the general population. Cad. Saude Publica 2013, 29, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehn, F.; Chachamovich, E.; Vidor, L.P.; Dall-Agnol, L.; Souza, I.C.C.; Torres, I.L.S.; Fregni, F.; Caumo, W. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. Pain Med. 2012, 13, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J.L.; Bishop, S.R.; Pivik, J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijma, A.J.; van Wilgen, C.P.; Meeus, M.; Nijs, J. Clinical biopsychosocial physiotherapy assessment of patients with chronic pain: The first step in pain neuroscience education. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2016, 32, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancey, C.P.; Reidy, J. Statistics without Maths for Psychology; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D.G. Practical Statistics for Medical Research; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.; Leckman, J.F.; Mayes, L.C.; Newman, M.A.; Feldman, R.; Swain, J.E. Perceived quality of maternal care in childhood and structure and function of mothers’ brain. Dev. Sci. 2010, 13, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, B.L.; Tottenham, N. The neuro-environmental loop of plasticity: A cross-species analysis of parental effects on emotion circuitry development following typical and adverse caregiving. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, A.; McEwen, B.S. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli-Neto, O.B.; Tawasha, K.A.S.; Romão, A.P.M.S.; Hisano, M.K.; Moriyama, A.; Candido-Dos-Reis, F.J.; Rosa-E-Silva, J.C.; Nogueira, A.A. History of childhood maltreatment and symptoms of anxiety and depression in women with chronic pelvic pain. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 39, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliki, M.N.; Apkarian, A.V. Nociception, pain, negative moods, and behavior selection. Neuron 2015, 87, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooten, W.M. Chronic Pain and Mental Health Disorders: Shared Neural Mechanisms, Epidemiology, and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.M.C.; Quarantini, L.C.; Daltro, C.; Pires-Caldas, M.; Koenen, K.C.; Kraychete, D.C.; De Oliveira, I.R. Comorbidade de sintomas ansiosos e depressivos em pacientes com dor crônica e o impacto sobre a qualidade de vida. Rev. Psiq. Clin. 2011, 38, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Eiland, L.; Hunter, R.C.; Miller, M.M. Stress and anxiety: Structural plasticity and epigenetic regulation as a consequence of stress. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.E.; Johnson, E.; Wechter, M.E.; Leserman, J.; Zolnoun, D.A. Catastrophizing: A predictor of persistent pain among women with endometriosis at 1 year. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 3078–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faedda, N.; Natalucci, G.; Piscitelli, S.; Fegatelli, D.A.; Verdecchia, P.; Guidetti, V. Migraine and attachment type in children and adolescents: What is the role of trauma exposure? Neurol. Sci. 2018, 39, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamvu, G.; Carrillo, J.; Ouyang, C.; Rapkin, A. Chronic pelvic pain in women: A review. JAMA 2021, 325, 2381–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Chen, L.; Fu, L.; Xu, S.; Fan, H.; Gao, Q.; Xu, Y.; Wang, W. Stressful parental-bonding exaggerates the functional and emotional disturbances of primary dysmenorrhea. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 23, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, K.A.M.; Oldehinkel, A.J.; Rosmalen, J.G.M. Parental overprotection predicts the development of functional somatic symptoms in young adolescentes. J. Pediatr. 2009, 154, 918–923.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sil, S.; Lynch-Jordan, A.; Ting, T.V.; Peugh, J.; Noll, J.; Kashikar-Zuck, S. Influence of family environment on long-term psychosocial functioning of adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thege, B.K.; Petroll, C.; Rivas, C.; Scholtens, S. The effectiveness of family constellation therapy in improving mental health: A systematic review. Fam. Process. 2021, 60, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stjernswärd, S. Getting to know the inner self exploratory study of identity oriented psychotrauma therapy-experiences and value from multiple perspectives. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 526399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E.; Wickramaratne, P.; Weissman, M. The stability of parental bonding reports: A 20-year follow-up. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 125, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Both groups |

|

|

| CPP group |

| |

| Pain-free group |

|

| Characteristics | CPP Group (n = 123) | Control Group (n = 123) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD; years) 1 | 37.0 ± 6.9 | 31.9 ± 7.2 | <0.001 c |

| Body mass index (mean ± SD; kg/m2) 1 | 27.5 ± 5.4 | 27.1 ± 5.8 | 0.310 |

| Monthly per capita income (mean ± SD; R$) 1 | 743.28 ± 496.68 | 748.08 ± 645.27 | 0.926 |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Skin color 2 | 0.447 | ||

| White | 31 (25.2) | 25 (20.3) | |

| Non-white | 92 (74.8) | 98 (79.7) | |

| Years of schooling 2 | 0.347 | ||

| <12 years | 46 (37.4) | 38 (30.9) | |

| ≥12 years | 77 (62.6) | 85 (69.1) | |

| Employment status 2 | 0.797 | ||

| Employed/in paid work | 67 (54.5) | 70 (56.9) | |

| Unemployed/retired/homemaker | 56 (45.5) | 53 (43.1) | |

| Marital status 2 | 0.893 | ||

| With a partner | 82 (66.7) | 80 (65.0) | |

| No partner | 41 (33.3) | 43 (35.0) | |

| Smoking 2 | 0.055 | ||

| Smoker | 10 (8.1) | 21 (17.1) | |

| Non-smoker | 113 (91.9) | 102 (82.9) | |

| Alcohol consumption 2 | 0.002 b | ||

| Yes | 48 (39.0) | 73 (59.3) | |

| No | 75 (61.0) | 50 (40.7) | |

| Physically active 2 | 0.517 | ||

| Yes | 26 (21.1) | 21 (17.1) | |

| No | 97 (78.9) | 102 (82.9) | |

| Physical abuse 2 | 0.003 b | ||

| Yes | 39 (31.7) | 18 (14.6) | |

| No | 84 (68.3) | 105 (85.4) | |

| Sexual abuse 2 | 0.062 | ||

| Yes | 27 (22.0) | 15 (12.2) | |

| No | 96 (78.0) | 108 (87.8) | |

| Relationship difficulties 2 | 0.001 b | ||

| Yes | 49 (39.8) | 24 (19.5) | |

| No | 74 (60.2) | 99 (80.5) | |

| Parity 2 | 0.148 | ||

| 0 | 29 (23.6) | 19 (15.4) | |

| ≥1 | 94 (76.4) | 104 (84.6) | |

| Chronic disease 2 | 0.071 | ||

| Yes | 93 (75.6) | 79 (64.2) | |

| No | 30 (24.4) | 44 (35.8) | |

| Abdominal/pelvic surgery 2 | 0.017 a | ||

| Yes | 96 (78.0) | 78 (63.4) | |

| No | 27 (22.0) | 45 (36.6) | |

| Anxiety 2 | <0.001 c | ||

| Yes | 98 (79.7) | 70 (56.9) | |

| No | 25 (20.3) | 53 (43.1) | |

| Depression 2 | 0.008 b | ||

| Yes | 90 (73.2) | 69 (56.1) | |

| No | 33 (26.8) | 54 (43.9) |

| Parenting Styles | CPP Group | Pain-Free Controls | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Maternal | 117 | 115 | |||

| Care | |||||

| Low | 71 | 60.7 | 52 | 45.2 | 0.026 a |

| High | 46 | 39.3 | 63 | 54.8 | |

| Overprotection | |||||

| Low | 35 | 29.9 | 34 | 29.6 | >0.999 |

| High | 82 | 70.1 | 81 | 70.4 | |

| Paternal | 91 | 94 | |||

| Care | |||||

| Low | 45 | 49.5 | 46 | 48.9 | >0.999 |

| High | 46 | 50.5 | 48 | 51.1 | |

| Overprotection | |||||

| Low | 22 | 24.2 | 30 | 31.9 | 0.314 |

| High | 69 | 75.8 | 64 | 68.1 | |

| Parenting Styles | Chronic Pelvic Pain | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted 1 | |||

| OR (95%CI) | p-Value | OR (95%CI) | p-Value | |

| Maternal | ||||

| Care | ||||

| High | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Low | 1.87 (1.11–3.15) | 0.019 a | 1.38 (0.74–2.57) | 0.315 |

| Overprotection | ||||

| Low | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| High | 0.98 (0.56–1.73) | 0.954 | 0.65 (0.33–1.28) | 0.212 |

| Paternal | ||||

| Care | ||||

| High | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Low | 1.02 (0.57–1.82) | 0.944 | 0.91 (0.46–1.81) | 0.799 |

| Overprotection | ||||

| Low | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| High | 1.47 (0.77–2.81) | 0.243 | 1.12 (0.51–2.43) | 0.782 |

| Pain Intensity | Duration of Pain | Catastrophizing | Anxiety | Depression | Maternal Care | Maternal Overprotection | Paternal Care | Paternal Overprotection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity | 1.0 | −0.051 | 0.342 c | 0.208 a | 0.165 | −0.101 | −0.098 | 0.087 | −0.153 |

| Duration of pain | 1.0 | 0.028 | −0.172 | −0.130 | 0.040 | −0.157 | 0.080 | −0.058 | |

| Catastrophizing | 1.0 | 0.271 b | 0.272 b | −0.128 | 0.185 a | −0.175 | 0.102 | ||

| Anxiety | 1.0 | 0.717 c | −0.184 a | 0.025 | −0.286 b | −0.003 | |||

| Depression | 1.0 | −0.219 a | −0.040 | −0.234 a | −0.003 | ||||

| Maternal care | 1.0 | −0.183 a | 0.224 a | 0.140 | |||||

| Maternal overprotection | 1.0 | −0.146 | 0.368 c | ||||||

| Paternal care | 1.0 | −0.079 | |||||||

| Paternal overprotection | 1.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siqueira-Campos, V.M.; Fernandes, L.J.H.; de Deus, J.M.; Conde, D.M. Parenting Styles, Mental Health, and Catastrophizing in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Case-Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013347

Siqueira-Campos VM, Fernandes LJH, de Deus JM, Conde DM. Parenting Styles, Mental Health, and Catastrophizing in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Case-Control Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013347

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiqueira-Campos, Vânia Meira, Lara Juliana Henrique Fernandes, José Miguel de Deus, and Délio Marques Conde. 2022. "Parenting Styles, Mental Health, and Catastrophizing in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Case-Control Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013347

APA StyleSiqueira-Campos, V. M., Fernandes, L. J. H., de Deus, J. M., & Conde, D. M. (2022). Parenting Styles, Mental Health, and Catastrophizing in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Case-Control Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013347