Abstract

Background: Sexual harassment in the workplace (SHWP) is highly prevalent and has a negative impact, including depression, on its victims, as well as a negative economic impact resulting from absenteeism and low productivity at work. This paper aims to outline the available evidence regarding the prevention of depressive symptoms among workers through policies and interventions that are effective in preventing SHWP. Methods: We conducted two systematic reviews. The first focused on the association of depression and SHWP, and the second on policies and interventions to prevent SHWP. We conducted a meta-analysis and a narrative synthesis, respectively. We identified 1831 and 6107 articles for the first and second review. After screening, 24 and 16 articles were included, respectively. Results: Meta-analysis results show a prevalence of depression of 26%, as well as a 2.69 increased risk of depression among workers who experience SHWP. Variables such as number of harassment experiences and exposure to harassment from coworkers and other people increase this risk. Conclusions: There is limited evidence regarding the effectiveness of policies and training to prevent SHWP, mostly focused on improvements in workers’ knowledge and attitudes about SHWP. However, there is no available evidence regarding its potential impact on preventing depression.

1. Introduction

Over the past 25 years, the issue of sexual harassment in the workplace (SHWP) has become more recognized [1]. Sexual harassment is defined as any unwelcome sexual behavior that is intimidating, hostile or offensive, which violates the victim’s human rights and dignity [2,3,4,5], and can be physical, psychological, verbal and non-verbal [2]. Behaviors that fall under this definition can range from sexual gestures and comments, unwelcome touching or repeated requests for dates to sexual violence and rape [1,2].

SHWP is a very common problem, with a prevalence between 20% and 50% reported in studies conducted in high-income countries (HICs) [2], and from 14.5% to 98.8% in low- and middle-income countries’ surveys (LMICs) [6]. Despite its high prevalence, it is usually underreported due to fear of retaliation or uncertainty about how to report it [2,3].

Most cases of SHWP can be categorized into two types: quid pro quo and hostile work environment [1,2,3]. Quid pro quo involves asking for sexual favors or allowing sexual advances in exchange for a job benefit or the continuation of employment. Rejection will result, explicitly or implicitly, in an action that affects the victim’s work. A hostile working environment is the result of the harassing behaviors towards the worker and, depending on the frequency and severity, evolve into an unbearable situation for the victim.

Certain workers are exposed to risk factors that increase their odds of experiencing SHWP [2]. Some examples include domestic workers, informal workers and people working with the public (patients, customers, etc.) [2,7]. Informal work is particularly relevant in LMICs, since it is more common [1].

SHWP has a significant negative impact on victims’ wellbeing [2,5]. Consequences include feelings of irritation, anger, fear, humiliation and stress [1]. Furthermore, it can result in workers missing career opportunities or resigning from their jobs [1,2,5]. Perhaps one of the most important consequences is depression, which is two to five times more frequent among people who experienced SHWP, compared to those who do not [8]. The psychological consequences of sexual harassment may be related to the type and severity of sexual harassment, the role of the perpetrator (e.g., coworkers, supervisors, clients), the victim’s attributes, and the access to social support and resources, among others.

In turn, depression has a negative impact on the workers’ quality of life [6,9] and a negative economic impact due to absenteeism and low productivity at work [2]. Therefore, addressing and preventing SHWP can, in turn, help reduce the prevalence of depression and its negative consequences among workers.

Both men and women can be victims of sexual harassment; however, women are more commonly affected [2,6,9]. Currently, there are several international policies and standards aimed at eliminating discrimination and violence against women, including SHWP. Examples of the international policies include the International Labour Organization (ILO) Declaration of Philadelphia, the ILO Convention No. 111, the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, and the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, among others [2,7]. In addition, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals include, among them, eliminating all forms of violence against women (Goal 5) and creating productive and decent work for all (Goal 8) [2]. These act as frameworks for businesses’ internal policies and initiatives.

Training is a common initiative to prevent SHWP, aiming to inform workers about internal policies, procedures and resources available, improve knowledge and attitudes regarding gender and help initiate change in the organizational culture [2,10]. Currently, an increasing number of workplaces provide training for managers, supervisors and workers, covering topics such as attitudes, stereotypes, social norms, unconscious bias, and bystander intervention, among others [2]. However, there is still limited evidence aiming at assessing the effectiveness of these interventions and its potential implications for the mental health of the workers.

This paper aims to outline the available evidence regarding the prevention of depressive symptoms among workers through policies and interventions that are effective in preventing SHWP. Specifically, we focused on three research questions: (1) What is the association between depression and SHWP? (2) What policies and interventions are effective at preventing SHWP? and (3) Do these policies and interventions have an impact on the prevention of depressive symptoms? In order to answer these questions, we conducted two systematic reviews, one focused on the association of depression and SHWP (RQ 1), and a second focused on policies and interventions to prevent SHWP (RQ 2 and 3).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

We conducted two systematic reviews, a meta-analysis for the first review and a narrative synthesis for both reviews. Both systematic reviews consisted of database searching. The search was conducted on 22 and 30 November on PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CENTRAL and Global Index Medicus. In addition, for the review focused on policies and interventions to prevent SHWP (review 2), we searched grey literature via the websites of six organizations (UN, UN Women, ILO, World Health Organization, National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, and Institute for the Study of Labor). The search strategy for both reviews can be found in Supplementary Material A. Key terms included “sexual harassment”, “workplace”, “intervention”, “depression”, among others.

We set out inclusion and exclusion criteria a priori for both reviews. Inclusion criteria were (1) published from the year 2000 onwards, (2) published in English or Spanish and (3) focused on working population. The exclusion criteria were (1) publications such as reviews, case reports, editorials, correspondence and conferences, and (2) publications in other languages.

2.2. Data Extraction and Analysis

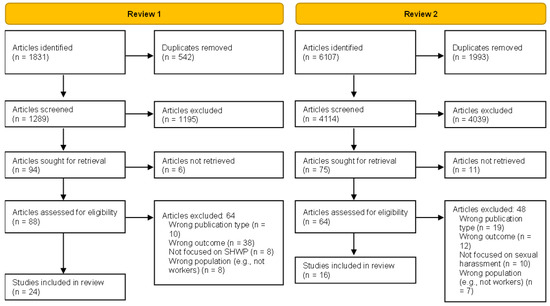

A minimum of two reviewers screened each article using the Rayyan software [11]. We identified 1831 and 6107 articles for the first and second review. Duplicates were identified automatically using Rayyan, then screened by the reviewers to ensure only identical papers were removed. After removing duplicates, 1289 and 4114 articles were screened by titles and abstracts to include only the papers related to the topic of the reviews. At this stage, the agreement percentage between raters was 95% (k = 0.415) for the first review and 98% (k = 0.403) for the second. Next, the reviewers read each article in full, leading to 24 articles were included for the first review and 16 articles for the second review. The agreement percentage for reviews 1 and 2 were 76% (k = 0.415) and 87% (k = 0.681) for the second. The reviewers were instructed to opt for including an article rather than excluding it when in doubt about their decision. Disagreements between the reviewers were settled by a third reviewer in virtual meetings, where each of the first two reviewers stated their reasoning to either including or excluding an article and then, with the input of the third reviewer, they reached consensus to make a final decision. The inclusion process is detailed in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) consort diagram (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Following this process, two reviewers extracted the relevant information (see Supplementary Material A) into an Excel spreadsheet, and any discrepancies in the information extracted were discussed to reach an agreement. This procedure required both reviewers to compare the data extracted and discuss any differences, revise the original data on the paper and reach a final agreement.

For the first review, a meta-analysis was conducted for papers reporting prevalence and/or odds ratios of depression as a result of SHWP, in order to synthesize the results across different studies. For the analysis of prevalence rates, percentages of individuals reporting depression (as measured on a validated clinical scale, or via clinical diagnosis) for those who had experienced SHWP, and associated 95% confidence intervals (calculated using the Wilson’s method which produces asymmetric confidence intervals in studies with low prevalence rates) were entered into STATA Version 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Heterogeneity among studies was estimated based on Cochran Q and reported using I2 (and 95% confidence interval of the I2). As I2 > 75% is considered indicative of high heterogeneity, we used a random-effects meta-analysis applying the metan code. For the meta-analysis of odds ratios, where odds ratios were not directly reported in the papers, these were calculated from a 2 × 2 contingency table for the rates of individuals with and without depression and with experience of no experience of SHWP. The resulting odds ratios and confidence intervals were then entered into STATA v17 and the metan command used to conduct a random-effects meta-analysis. The included papers were not enough to be conduct a meta-regression to explore how participant and study characteristics were linked to depression prevalence rates and ORs. Therefore, the findings are summarized narratively.

For the second review, a narrative synthesis was conducted to summarize the findings from the included studies. This process involved identifying common key topics between the included articles, such as the setting in which the study took place, the participants characteristics, the policy or intervention’s characteristics, duration, frequency, the measures used to assess its impact, and the main findings.

2.3. Quality Assessment

Included articles were assessed by two researchers using critical appraisal tools to assess the risk of bias. For the first review, we used the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS tool) [12]. For the second review, we used the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies [13]. The researchers compared their assessments, and any disagreements were discussed and solved among them.

2.4. Protocol Registration

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO, accessed on 17 December 2021). Registration number—CRD42021291829.

3. Results

3.1. Review 1: Association between Depression and SHWP

For the first review, two-thirds of the articles included came from HICs (16/24) [8,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], followed by articles from LMICs (7/24, 3 from upper-middle-income [29,30,31] and 3 from lower-middle-income countries [32,33,34]), and only one article from a low-income country [35]. Lastly, one article used data from different countries, mostly HICs [36]. Regarding the year of publication, two-thirds of the articles were published in the 2010s (16/24) [8,14,15,16,17,18,19,22,23,24,28,30,31,32,34,36], three articles in the 2000s [25,29,35] and five articles in the 2020s [20,21,26,27,33]. Regarding the methodology, most of the studies were cross-sectional (18/24) [14,15,16,17,18,20,21,22,25,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], while the rest were cohort studies (6/24) [8,19,23,24,26,27].

The great majority (20/24) used a standardized scale to measure depressive symptoms [8,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,34,35,36], while the rest (4/24) relied on self-reported experience of depression [20,29,32,33]. Further details of the studies can be found in Supplementary Material B.

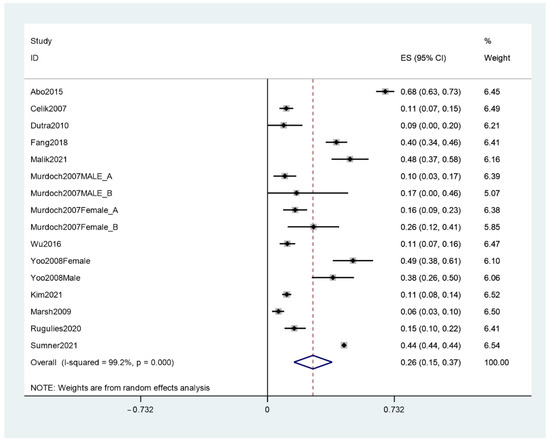

Among the included articles, 12 reported the prevalence rates of depression among workers who experienced SHWP [14,20,25,26,27,28,29,30,32,33,35,36]. Meta-analysis results show a combined prevalence of depression of 26% (95% CI, 0.15–0.37). However, the heterogeneity of studies is 99.2% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the prevalence of depression among workers who experienced SHWP.

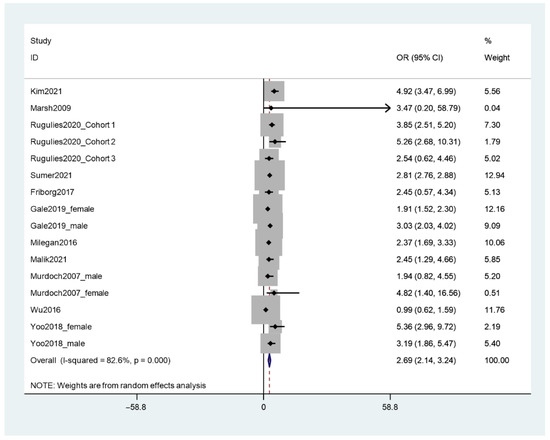

Similarly, eleven included articles reported odd ratios of depression as a result of SHWP. The results indicated that workers who experience SHWP have 2.69 higher odds of depression compared to workers who do not experience SHWP (see Figure 3); however, again, heterogeneity was high (82%).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of odd ratios of depression among workers who experienced SHWP.

Results from the narrative summary indicate a range of prevalence rates for depression in people who experience SHWP from 5.1% to 67.9%. Similarly, the odds of developing depression following SHWP increase based on the number of SHWP events experienced or who was the perpetrator (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Narrative summary of the association between depression and SHWP.

3.2. Review 2: Policies and Interventions to Prevent SHWP and Depression

For the second review, most included articles were from HICs, particularly the United States (15/16) [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51], and one article was from Nigeria, a lower-middle-income country [52]. Around two thirds of the articles were published in the 2010s (10/16) [39,40,41,43,45,46,47,49,50,53], 4 articles in the 2000s [38,42,44,52] and 2 articles in the 2020s [48,51]. Most studies used a cross-sectional design (9/16) [38,39,41,42,46,48,49,50,53], four studies were quasi-experimental [40,43,51,52] and three were RCTs [44,45,47].

Regarding the type of participants, five studies focused on health professionals [43,48,49,50,51], four focused on managers and human resource workers [39,41,45,46], followed by studies focused on the military [42], police [53], government employees [38], university employees [47], and apprentices [52], and two studies on workers from a variety of industries [40,44]. Further details of the studies can be found on Supplementary Material C.

None of the included articles focused on how the prevention of SHWP is associated with the prevention of depression directly. Only one study measured depressive symptoms and burnout. The study controlled for these variables to assess the effectiveness of a computer-based training (CBT) to a CBT plus peer facilitation training [43].

The studies have been categorized into two groups: evidence from policies and evidence from SHWP training.

3.3. Evidence from Policies

In total, five articles focused on SHWP policies. One study focused on grievance procedures for SHWP cases and found these are associated with diminished access of women to management positions in settings where men hold more positions of power, and this effect disappears in spaces where women hold more management jobs [41].

The other four studies focused on the impact of SHWP policies on reporting. One experimental study highlighted the importance of having comprehensive and explicit policies. The results showed that a zero-tolerance policy increases the likelihood of reporting SHWP, compared to a less specific policy or no policy [45]. The effect of the policy on the likelihood of reporting the case was higher for a moderate form of SHWP presented (i.e., comments about the body), compared to a more severe quid pro quo SHWP scenario, which is important, since the former is a more common form of SHWP and usually goes unreported.

Another study, focusing on the Dutch police force, showed SHWP rates were slightly higher among police divisions with more comprehensive policies (written statement, grievance procedures, training, etc.), compared to divisions with less comprehensive policies [53]. The authors interpret this result as comprehensive policies increasing awareness of SHWP, leading to more reported cases. Similarly, the other two studies reported an increase in reported cases after implementing the SHWP policy in their workplaces [49,50].

Some of the contents reported in the policies mainly include prevention efforts, reporting and grievance, as well as a clear and explicit stance on SHWP (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Contents of SHWP policies.

3.4. Evidence from Training

Eleven included articles focused on training, which can be further subcategorized into two types: observational (4/11) and implementation studies (7/11). Observational studies focused on assessing the impact of SHWP prevention training already taking place in specific work settings, while implementation studies focused on conducting and assessing the impact of training.

Regarding the observational studies, two articles focused on the impact of training on the participants’ perceptions regarding SHWP. One study targeted civil government employees [38], while the other centered around the military [42]. The results from both studies showed benefits from training, including increased self-reported sensitivity to the issue [38], increased awareness of conducts that can be labelled as SHWP, particularly in men receiving the training [38], as well as higher levels of intolerance towards harassment and more perceived efforts from the workplace to prevent it [42].

The other two observational studies focused on specific training features and their impact on preventing SHWP. The first study showed the quantity of training and the interaction between quantity and recency are only modest predictors of increased sensitivity to identify SHWP [39]. The second study revealed that the number of pre-training and post-training activities, such as needs assessment and refresher sessions, respectively, is associated with the perceived success of the training. However, this association is significant only when the perceived reason to conduct the training was related to improving the workplace, instead of legal compliance [46]. In addition, a greater number of post-training activities was associated with a lower perceived frequency of SHWP reports [46].

The implementation studies showed SHWP prevention training has an impact on specific outcomes. The most common and supported evidence was increased knowledge and awareness about SHWP [40,47,48,52,54]. Additionally, in studies where the training aimed to provide specific skills to manage SHWP scenarios, there is a reported increase in confidence [54], self-efficacy [48] and preparedness among workers [51]. One study also identified a decrease in perceived barriers and increased intentions to intervene in these situations [48]. Only two studies measured effects over time in the prevalence of SHWP, and both found a decline in reported harassment at follow-up (6 months) [52,54]. Lastly, one study found training reduced the intention to confront the perpetrator [44]. The researchers attribute this unexpected result to the inclusion of potential consequences of confronting in the training contents, including retaliation and isolation from coworkers, which may have discouraged the participants.

Regarding training methods, nine out of the eleven studies reported in-person training, while the other two compared computer-based with in-person training, finding no significant differences between methods [47,54]. Training usually consisted of a single session lasting around 1 to 1.5 h, mostly using a lecture format with some interactive components, most frequently discussions. Common topics covered were the definition and types of SHWP, as well as how to identify SHWP, with a few studies adding some strategies to manage and address the situation (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of SHWP prevention training (Only eight out of the eleven studies focused on training reported the number of sessions, duration and format).

3.5. Quality of Studies

The studies included in the first review were assessed using the AXIS tool [12]. Overall, the studies included meet the reporting requirements expressed in the tool. However, there were common specific limitations in study reporting, specifically regarding the justification of sample size, information about the non-responders, and the internal consistency of the results (see Supplementary Material D).

Regarding the second review, the studies were assessed using the EPHPP tool. The majority of studies were rated as weak on quality, which is expected considering most were not RCTs, with only two obtaining a moderate score (see Supplementary Material E).

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevention of Sexual Harassment and Depression

The aim of this review was to examine whether SHWP prevention has an impact on preventing depression among workers. Our first review confirms SHWP is a predictor and a risk factor for depression. In addition, certain variables, such as the number of SHWP experiences and combined exposure to harassment from clients or customers and coworkers, increase the risk for depression. However, we found no direct evidence of the effectiveness of SHWP policies and training on preventing depression. Based on the identified association between SHWP and depression, we can infer early prevention of SHWP, through policies and training, could reduce the risk and prevalence of depression among workers and lead to an improvement in their mental health.

The available evidence regarding SHWP prevention policies and interventions is limited and weak. The most common evidence focused on SHWP prevention training; however, evidence of effectiveness was still somewhat small (11 studies). This result is in line with a report from UN Women conducted in 2020, which states there is a limited amount of literature on training [10]. Despite this limitation, the majority of studies report that both policies and training improve awareness regarding SHWP; and, in some cases, skills to address the situation. However, further research is required to assess the potential effect of training and prevention policies on workers’ depression levels.

4.2. Scalability, Applicability and Implementation

The majority of studies included in this review were conducted in formal work environments within HICs, therefore the applicability of our results to other contexts should be carefully assessed and adapted. Studies most commonly focused on health professionals and the military, therefore the results can be easily extrapolated to these workplaces. Further research is required to assess the applicability of these initiatives to LMICs, where informal work is more common. However, most countries adhere to international regulations and have national legislations regarding SHWP [55], which provide the framework to implement SHWP prevention measures.

Implementing SHWP zero-tolerance policies and training can be easily adapted to different types of workplaces with certain policy aspects potentially increasing their impact. Firstly, the workers’ perception of the employer’s intention to implement these initiatives is highly relevant to engage them with the policy [46]. It can be quite common for these policies and training to be implemented only to comply with a legal requirement, or as merely symbolic [10], which can diminish effectiveness. Secondly, it is important to tailor these initiatives to the context in which they are implemented, particularly training, using examples relevant to the types of SHWP situations they may experience and providing relevant information to address and manage it through role-playing [40,43,48,51]. Thirdly, training should be continuous and not restricted to a single moment in time [10]. Fourthly, as identified in the evidence, computer-based and instructor-led training methods provide similar outcomes [47,54]. Therefore, both methodologies can be used in combination or separately, according to each workplace’s conditions and after assessing the skills of the participants, including their technology literacy. Finally, making policies comprehensive and explicit regarding the stance on SHWP will provide a better framework for the workers to report cases [45,53]. Consequently, a key aspect to consider is to develop and inform workers about the grievance procedures that take place after a case is reported. Considering an increased awareness of SHWP could lead to a higher number of cases, as reported in the evidence from policies [45,49,50,53], it is crucial for workers to know how the workplace handles the reports and how they bring them to a resolution.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge this is the first review aiming to outline the available evidence regarding the prevention of depressive symptoms among workers through policies and interventions that are effective in preventing SHWP. We included evidence from both HICs and LMICs.

One limitation is that the great majority of studies identified come from HICs. While it can be inferred that the results would be similar in similar HIC settings, more research is required, particularly for more challenging working conditions such as informal work, which is common in LMICs, and where these results might not be as generalized as for HICs. A second limitation is the concise descriptions of the training contents and methodologies, which made comparison among studies difficult. Given the nature of this review, we did not seek to identify differences in the methodologies used; however, more detailed descriptions of the training contents would have been an important complement to the evidence, as well as a facilitator to replicate the methodologies used. Another limitation is that most studies lack standardized measures to assess the effectiveness of the training programs, mainly relying on self-report of knowledge and attitudes instead of the reported cases of sexual harassment. This also limits the comparability among studies and highlights a gap that needs to be filled in order to better assess and compare the quality of the studies. Other limitations related to the methodology are including only studies in English and Spanish, and from the year 2000 onwards.

5. Conclusions

SHWP is a prevalent and important issue to tackle due to its impact on the workers’ lives, particularly their mental health. Workers who experience SHWP are at a higher risk for depression, and certain variables, such as number of harassment experiences and exposure to harassment from people other than coworkers, increase this risk.

There is limited evidence regarding the effectiveness of policies and training to prevent SHWP, and there is no evidence regarding its potential impact on preventing depression. In addition, most of the evidence comes from HICs. Despite this, the evidence indicates that training and policies can improve awareness, knowledge and resources to address SHWP in the daily lives of workers. Due to the aforementioned link between SHWP and depression, it can be inferred that preventing the former would most likely reduce the risk for depression among workers, however further research is required. Regardless of the limited evidence, it is crucial to ensure workplaces set up and implement procedures to address SHWP for the benefit of all workers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph192013278/s1, Supplementary Material A: Search terms for databases and data extracted. Supplementary Material B: Included articles in review 1. Supplementary Material C: Included articles in review 2. Supplementary Material D: Quality assessment of studies in review 1. Supplementary Material E: Quality assessment of studies in review 2.

Author Contributions

F.D.-C., M.T., L.H.-P. and V.J.B. conceived and designed the review. M.T. and L.H.-P. extracted the data. M.T., L.H.-P. and V.J.B. analyzed the data. M.T. drafted the initial version of this manuscript. F.D.-C., L.H.-P. and V.J.B. reviewed the manuscript and provided substantial inputs. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was commissioned by the Wellcome Trust. For the purpose of open access, Wellcome has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Roberto Torres, Leonardo Albitres, Sumiko Flores and Daniela Ramirez for their contributions during the data extraction process, as well as the lived experience advisory panel, for their insights and reflections throughout the review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- International Labour Organization. Sexual Harassment at Work: National and International Responses; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women; International Labour Organization. Handbook Addressing Violence and Harassment against Women in the World of Work; UN Women Headquarters: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Sexual Harassment in the Workplace in Nepal; International Labour Organization (ILO): Kathmandu, Nepal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Guidelines on Sexual Harassment Prevention at the Workplace; International Labour Organization (ILO): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Preventing and Responding to Sexual Harassment at Work: Guide to the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal); International Labour Organization (ILO): New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan, M.; Wamoyi, J.; Pearson, I.; Stockl, H. Measurement and prevalence of sexual harassment in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Women. Sexual Harassment in the Informal Economy: Farmworkers and Domestic Workers; UN Women: New York, NU, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, S.; Mordukhovich, I.; Newlan, S.; McNeely, E. The Impact of Workplace Harassment on Health in a Working Cohort. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurston, R.C.; Chang, Y.; Matthews, K.A.; von Kanel, R.; Koenen, K. Association of Sexual Harassment and Sexual Assault with Midlife Women’s Mental and Physical Health. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Women. Stepping up to the Challenge: Towards International Standards on Training to End Sexual Harassment; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.H.; Ciliska, D.; Dobbins, M.; Micucci, S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2004, 1, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, L.; Grubbs, K.; Greene, C.; Trego, L.L.; McCartin, T.L.; Kloezeman, K.; Morland, L. Women at war: Implications for mental health. J. Trauma Dissociation Off. J. Int. Soc. Study Dissociation (ISSD) 2011, 12, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friborg, M.K.; Hansen, J.V.; Aldrich, P.T.; Folker, A.P.; Kjær, S.; Nielsen, M.B.D.; Rugulies, R.; Madsen, I.E.H. Workplace sexual harassment and depressive symptoms: A cross-sectional multilevel analysis comparing harassment from clients or customers to harassment from other employees amongst 7603 Danish employees from 1041 organizations. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, G.M.; Laws, H.; Park, C.L.; Hoff, R.; Hoffmire, C.A. Meaning in life following deployment sexual trauma: Prediction of posttraumatic stress symptoms, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 278, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, G.C.; Perrin, N.A.; Moss, H.; Laharnar, N.; Glass, N. Workplace violence against homecare workers and its relationship with workers health outcomes: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, M.A.; Stanley, I.H.; Spencer-Thomas, S.; Joiner, T.E. Women Firefighters and Workplace Harassment: Associated Suicidality and Mental Health Sequelae. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2017, 205, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, J.N.; Staff, J.; Mortimer, J.T.; Uggen, C.; Blackstone, A. The Impact of Sexual Harassment on Depressive Symptoms during the Early Occupational Career. Soc. Ment. Health 2011, 1, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R. Associations between Workplace Violence, Mental Health, and Physical Health among Korean Workers: The Fifth Korean Working Conditions Survey. Workplace Health Saf. 2021, 70, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, T.F.; Sølvberg, N.; Sundgot-Borgen, C.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Sexual Harassment in Fitness Instructors: Prevalence, Perpetrators, and Mental Health Correlates. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 735015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud Aznar, M.P.; Velasco Portero, T.; Sánchez Tovar, L.; Espejo, M.J.D.P.; Voltes Dorta, D. Acoso Laboral en Mujeres y Hombres: Un estudio en la población española. Salud De Los Trab. 2013, 21, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, E.B.; Murdoch, M.; Erbes, C.R.; Arbisi, P.; Polusny, M.A. Impact of Deployment-Related Sexual Stressors on Psychiatric Symptoms after Accounting for Predeployment Stressors: Findings from a U.S. National Guard Cohort. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millegan, J.; Wang, L.; LeardMann, C.A.; Miletich, D.; Street, A.E. Sexual Trauma and Adverse Health and Occupational Outcomes among Men Serving in the U.S. Military. J. Trauma. Stress 2016, 29, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, M.; Pryor, J.B.; Polusny, M.A.; Gackstetter, G.D. Functioning and psychiatric symptoms among military men and women exposed to sexual stressors. Mil. Med. 2007, 172, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rugulies, R.; Sørensen, K.; Aldrich, P.T.; Folker, A.P.; Friborg, M.K.; Kjær, S.; Nielsen, M.B.D.; SørensenaId, J.K.; Madsen, E.H. Onset of workplace sexual harassment and subsequent depressive symptoms and incident depressive disorder in the Danish workforce. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J.A.; Lynch, K.E.; Viernes, B.; Beckham, J.C.; Coronado, G.; Dennis, P.A.; Tseng, C.-H.; Ebrahimi, R. Military Sexual Trauma and Adverse Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Comorbidity in Women Veterans. Women’s Health Issues Off. Publ. Jacobs Inst. Women’s Health 2021, 31, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, J.; Kim, S.S. Sexual harassment and its relationship with depressive symptoms: A nationwide study of Korean EMS providers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 62, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, Y.; Celik, S.S. Sexual harassment against nurses in Turkey. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2007, 39, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Zhao, X.; Yang, H.; Sun, P.; Li, Y.; Jiang, K.; Li, P.; Jiao, M.; Liu, M.; Qiao, H.; et al. Depressive symptoms and workplace violence-related risk factors among otorhinolaryngology nurses and physicians in Northern China: A crosssectional study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lyu, Y.; Ye, Y. Workplace sexual harassment, workplace deviance, and family undermining. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo Ali, E.A.; Saied, S.M.; Elsabagh, H.M.; Zayed, H.A. Sexual harassment against nursing staff in Tanta University Hospitals, Egypt. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2015, 90, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Inam, H.; Martins, R.S.; Janjua, M.B.N.; Zahid, N.; Khan, S.; Sattar, A.K.; Khan, S.; Haider, A.H.; Enam, S.A. Workplace mistreatment and mental health in female surgeons in Pakistan. BJS Open 2021, 5, zrab041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.; Sultana, S.; Imtiaz, I. The Trauma of Sexual Harassment and Its Mental Health Consequences among Nurses. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. 2015, 25, 675–679. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, J.; Patel, S.; Gelaye, B.; Goshu, M.; Worku, A.; Williams, M.A.; Berhane, Y. Prevalence of workplace abuse and sexual harassment among female faculty and staff. J. Occup. Health 2009, 51, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.C.; Donnelly-McLay, D.; Weisskopf, M.G.; McNeely, E.; Betancourt, T.S.; Allen, J.G. Airplane pilot mental health and suicidal thoughts: A cross-sectional descriptive study via anonymous web-based survey. Environ. Health A Glob. Access Sci. Source 2016, 15, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Williams, A.; Thomas, N. Engaging with a Web-Based Psychosocial Intervention for Psychosis: Qualitative Study of User Experiences. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e16730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antecol, H.; Cobb-Clark, D. Does Sexual Harassment Training Change Attitudes? A View from the Federal Level. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 826–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, G.E.; Hindman, H.D.; Huelsman, T.J.; Bergman, J.Z. Managing workplace sexual harassment: The role of manager training. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2014, 26, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Kramer, A.; Woolman, K.; Staecker, E.; Visker, J.; Cox, C. Effects of a brief pilot sexual harassment prevention workshop on employees’ knowledge. Workplace Health Saf. 2013, 61, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbin, F.; Kalev, A. The promise and peril of sexual harassment programs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 12255–12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, A.X.; Laurence, J.H. Examining the impact of training on the homosexual conduct policy for military personnel. Mil. Psychol. 2009, 21, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.; Hanson, G.C.; Anger, W.K.; Laharnar, N.; Campbell, J.C.; Weinstein, M.; Perrin, N. Computer-based training (CBT) intervention reduces workplace violence and harassment for homecare workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, C.B. The impact of training and conflict avoidance on responses to sexual harassment. Psychol. Women Q. 2007, 31, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R.K.; Eaton, A.A. How organizational policies influence bystander likelihood of reporting moderate and severe sexual harassment at work. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2018, 30, 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.L.; Kulik, C.T.; Bustamante, J.; Golom, F.D. The impact of reason for training on the relationship between ‘Best Practices’ and sexual harassment training effectiveness. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2010, 21, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preusser, M.K.; Bartels, L.K.; Nordstrom, C.R. Sexual harassment training: Person versus machine. Public Pers. Manag. 2011, 40, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relyea, M.R.; Portnoy, G.A.; Klap, R.; Yano, E.M.; Fodor, A.; Keith, J.A.; Driver, J.A.; Brandt, C.A.; Haskell, S.G.; Adams, L. Evaluating bystander intervention training to address patient harassment at the Veterans Health Administration. Women’s Health Issues 2020, 30, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridenour, M.L.; Hendricks, S.; Hartley, D.; Blando, J.D. Workplace Violence and Training Required by New Legislation among NJ Nurses. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, e35–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.; Whittemore, A.; Tsen, L.C. Instituting a culture of professionalism: The establishment of a center for professionalism and peer support. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2014, 40, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, L.E.; Barlow, P.B.; Scruggs, B.A.; Oetting, T.A.; Martinez, D.A.; Abràmoff, M.D.; Shriver, E.M. Tools for Responding to Patient-Initiated Verbal Sexual Harassment: A Workshop for Trainees and Faculty. MedEdPORTAL 2021, 17, 11096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawole, O.I.; Ajuwon, A.J.; Osungbade, K.O. Evaluation of interventions to prevent gender-based violence among young female apprentices in Ibadan, Nigeria. Health Educ. 2005, 105, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haas, S.; Timmerman, G.; Höing, M.; Zaagsma, M.; Vanwesenbeeck, I. The impact of sexual harassment policy in the Dutch police force. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2010, 22, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Seidman, G.; Atun, R. Does task shifting yield cost savings and improve efficiency for health systems? A systematic review of evidence from low-income and middle-income countries. Hum. Resour. Health 2017, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Compendium of International and National Legal Frameworks on Sexual Harassment in the Workplace; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).