Self-Reported Experiences of Midwives Working in the UK across Three Phases during COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

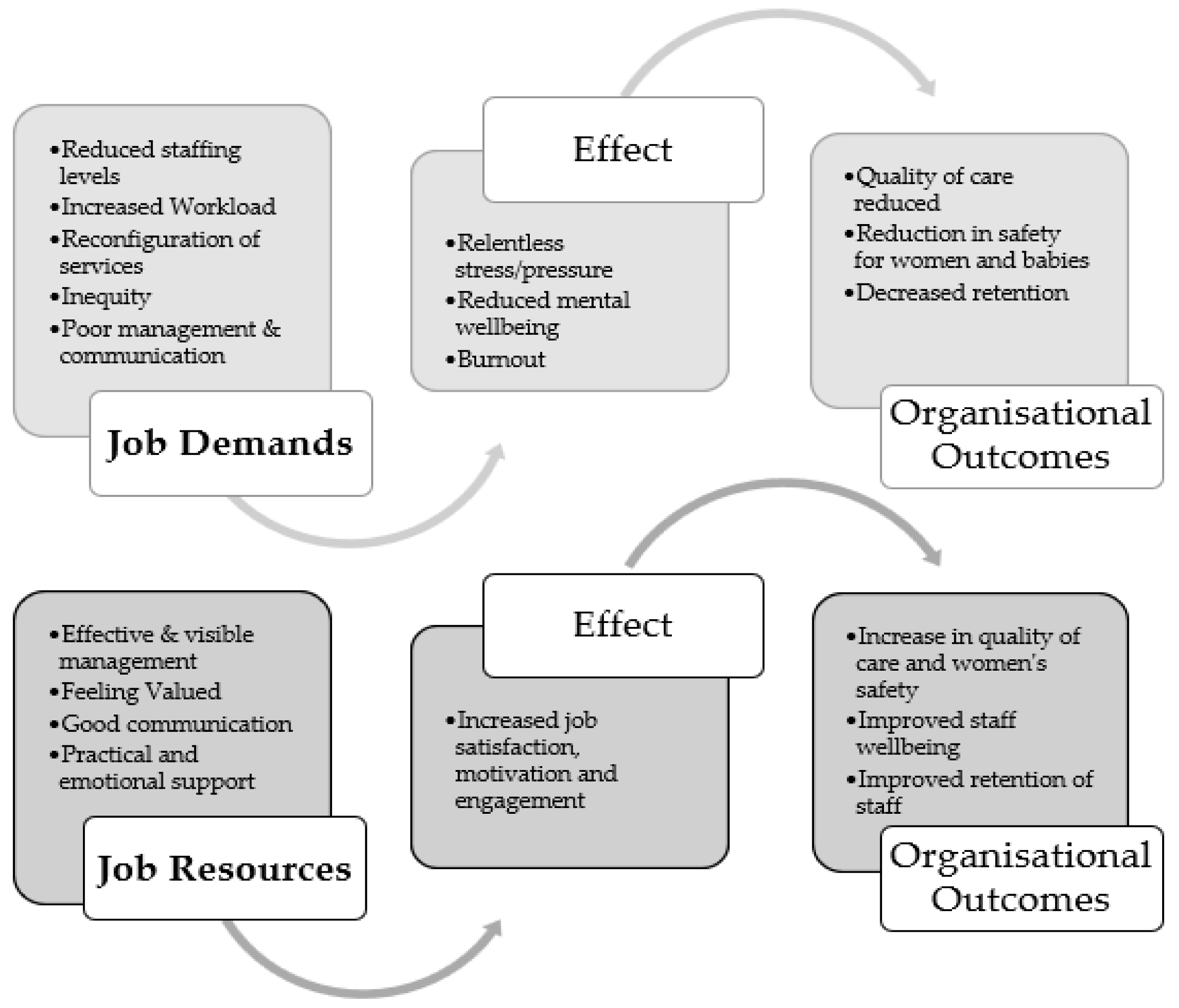

Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Participants

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Thematic Analysis

3.3. Relentless Stress/Pressure

3.3.1. Work Practices

I’m a midwife working in both community and hospital environments to provide continuity of care for women. This requires me to be on call 24/36 h per week for women living in the area I cover. However, the health board I work for now wish for me to go on call for the hospital cover due to short staffing with COVID. We are expected to do excess work without excess pay. Due to staff shielding at home midwives are already covering other midwives’ caseload so having higher patient numbers that what was deemed appropriate for this model or care. I think now, midwives are starting to feel burnt out, with the rapidly changing protocols and excess work. (Scotland, Hospital, Phase 1)

The pressure at times feels relentless, service users can often become critical and voice their opinions with staff they come in contact even though that department is not theirs. eg criticism of waiting times for ED (emergency department treatment) or for cancer treatment is not something we in maternity services can respond to other than to acknowledge that currently there is widespread pressure within the NHS. (NI, Hospital, Phase 2)This caused monumental stress and poor mental health as it felt like we were being used as a staff bank while juggling oversubscribed caseloads of women in rapidly evolving guidelines as well as coming into contact with the most amount of people/in and out of their homes. (Scotland, Hospital and Community, Phase 2)

Increased levels of stress. Feeling scared of impact of COVID and potentially sharing it with loved ones. A change in delivery of service or minimising home visits, but as only midwifery working keeping ladies on longer than usual. Feeling extreme pressure to get everything done (Wales, Community, Phase 3)

I had a panic attack whilst driving on the motorway on my way to work in March. I’ve not been at work since then. I’ve been diagnosed with OCD, PTSD, intrusive thoughts and anxiety (England, Other, Phase 3)Everyday just feels the same and there seems to be no enjoyment or things to look forward to anymore, I sometimes feel there will be no end to this situation. I have withdrawn somewhat and get quite angry and frustrated (Scotland, Hospital, Phase 3)

3.3.2. Client Related

Women not having their birth partner for all of their appointments and in the postnatal wards. Women were highly anxious and tearful. (NI, Hospital, Phase 2)I have been dealing with increased verbal aggression and hostility from patients and their families, due to their frustrations at poorer quality of care. (Wales, Community, Phase 3)No visitors, so extra help needed by New Mums (England, Hospital, Phase 3)

3.4. Reconfiguration of Services

3.4.1. Ante/Post-Natal, Home Birth, Home Visit Changes

Increased use of telephone triage effectively reducing the number of face-to-face triage admissions. Conversion of MLU rooms to COVID-19 isolation areas and removal of water birth availability (England, Hospital, Phase 1)Increase in women wishing local Midwife birth Centre and Homebirths. (Wales, Community, Phase 1)The MLU has been closed to deal with the virus so we have lost a lot of our services and everything operating out of the obstetric unit. This means all our women have to give birth in the obstetric unit which, for some, is really far away. Lost the home birth service as well. (England, Hospital, Phase 1)

3.4.2. Impact of Closure/Changes to Other Services

Increased dramatically as GPs didn’t allow clinics or women into practice, areas all clinics had to be centralised into a hub (NI, Hospital, Phase 2)

3.4.3. Additional Workload

Increased workload as the low risk unit MLU closed, to be used for suspected and positive COVID patients. With high risk staff being redeployed the skill mix isn’t great. (NI, Hospital, Phase 1)Service provision moved out of GP surgeries into Health Centres we have moved 3 times into different centres since the pandemic began. The last move was as a consequence of the rooms becoming a hub for COVID vaccinations. Some elements of care are now carried out on the phone where staff are able to work from home once a week or whilst isolating if well (England, Community, Phase 2)

A&E closed as a result we had to take on early pregnancy. More inductions and C/S (Caesarean sections) from neighbouring hospital (same Trust). High volume of phone calls booking patients in for induction or C/S from antenatal clinics from both sites not to mention our own workload in the admission and assessment unit, and only 1 midwife and maternity support worker, a receptionist would be handy! By the time we put apron and gloves on the phone rings non stop and we have to wash hands and go and answer the phone several times while dealing with patients. Also extra time required for COVID swabbing, it has been challenging and exhausting. (NI, Hospital, Phase 1)More admin with visiting questionnaires, contact tracing and arranging visiting time slots. This has been an expected midwifery staff role! (Scotland, Hospital, Phase 3)

I have seen significantly increased numbers of COVID positive women since July, compared to back in March to July. Which is very stressful & causes the worry of possibly bringing the illness home to family. PPE not great quality—worry it’s not fit for purpose. (NI, Hospital, Phase 2)Increased demand for Complex midwifery care for women with COVID. Increased pressure on staff due to midwives being allocated to care for COVID women, leaving the rest of the ward understaffed. (England, Hospital, Phase 3)

3.5. Protection of Self and Others (Physical and Emotional/Psychological)

3.5.1. PPE

When I raised a concern that we were not allowed to wear an ffp3 mask when caring for a labouring woman with suspected COVID I felt that I was in very close proximity and for an extended amount of time with her breathing Entonox I felt I wasn’t protected when I was only wearing a surgical mask. I spoke to my line manager who then spoke to the risk assessment manager and it was agreed we are now allowed an ffp3 mask but only for labour. This was very stressful for me but the end result was good. (NI, Hospital, Phase 1)Advice around PPE was inadequate in the few weeks and this advice changed frequently. It was felt that the advice depended on the available supply of PPE! (Wales, Other, Phase 1)Communication was more difficult due to masks. All just added to level of stress as at the beginning it was not known how COVID was transmitted and I had to have a student midwife with me on community who could not drive and was using public transport at the time. We had no advice at the time except we were to wear masks all the time and drive with the windows down. This was not always practical if going on longer distances and higher speeds (Scotland, GP Based, Phase 3)

3.5.2. Home/Work Balance

I find it difficult to separate the two and often have to complete e-learning at home. Non work responsibilities seem to take a back seat as I am so tired (Wales, Community, Phase 2)Work has overtaken home—I am behind on all home ‘stuff’ and on the back foot with family plans. Not enough brain space to be in control of it (England, Hospital, Phase 3)Non-work—difficult to be school teacher on top of all the work that we had to do and deal with all the stress and pressure. Felt I had little time for parenting. No outlet to go out with friends or family to celebrate birthdays or occasions and this is a huge loss to life. (NI, Hospital, Phase 3)

3.5.3. Protection of Family

Husband has become sole carer for my children as I have often had to work longer hours and overtime shifts. My mum has been shielding as she is elderly and due to me working in the NHS she has had to depend on meals on wheels etc and my daughter helping her with shopping etc as I am staying away from her in order to protect her (Wales, Hospital, Phase 1)My Husband has been shielding, I have had to live in a separate part of the house so I have had to change clothing in the car, clean down everything daily, wash all things delivered to the house. It has meant I stay at work longer to finish things I could have done at home (England, Community, Phase 3)

3.6. Workforce Challenges

3.6.1. Staffing

Due to staff shielding at home midwives are already covering other midwives’ caseload so having higher patient numbers than what was deemed appropriate for this model or care. I think now, midwives are starting to feel burnt out, with the rapidly changing protocols and excess work. (Scotland, Hospital, Phase 1)Significant staff shortages due to sickness or shielding, doubled caseload due to less midwives, changing ways of working, more use of technology, increased anxiety/dissatisfaction from some service users. (Wales, Community, Phase 3)

3.6.2. Management and Leadership

The most important thing was INFORMATION! Excellent daily communication from the CEO (Trust Chief Executive) kept us all in the loop! (England, Hospital, Phase 1)Having an excellent Manager who I can turn to for advice and excellent colleagues who all support each other. (NI, Hospital, Phase 2)

3.6.3. Communication

Clearer messages in the early days—conflicting messages on PPE from professional bodies, Department of Health etc. Once the PHE (Public Health England) advice came out everything was much clearer. (NI, Hospital Phase 1)Ask the staff what works well as well as reading the statistics. Staff are doing over and above what is expected of them to get the best outcomes for mums and babies. Perhaps it would make staff feel their opinion is valued. (Scotland, Hospital, Phase 1)Managers to clinically work at point of care to see pressure of work, as most managers not clinical anymore. Work pressure and lack of resource, and staff substantially increased over last years. (NI, Hospital, Phase 2)

3.6.4. Inequity

Dealing with the blatant racism and discrimination in the workplace (England, Community, Phase 1)Terms and conditions weren’t fair. Staff who were shielded got to keep annual leave and those who worked throughout got to keep none!!!! This was demoralising and caused animosity amongst staff (NI, Hospital, Phase 2)We are left to get on with it. Management tell us don’t do this etc. Yet they (are) working from home. Condensed hours and not visible when we need them. Want to keep midwifery led “open at all costs” to detriment of high risk patients and staff in those areas. Workload disproportionately allocated. (NI, Hospital, Phase 2)Haven’t felt at all supported by my employer during the pandemic. I enjoy working with patients/service users but struggle with an oppressive, undermining culture that has become more evident during the pandemic. (NI, Hospital, Phase 3)

3.6.5. Feeling Valued

Colleagues have been inspirational, newsletters frequently and emails of praise and thanks from management (NI, Hospital, Phase 1)Emails from chief executive saying that appreciated the work as we’re doing. Facebook campaign to recognise unsung heroes, good for morale, we are all in it together. (NI, Community, Phase 1)

At the start the public showed appreciation of the care provided but as time has gone on it feels it’s always give and more is expected of you. And despite being kind, well mannered and wanting the best for those you provide care for, the relentless pressure and increase workload it has become frustrating. (NI, Hospital, Phase 2)

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Open-Ended Questions Used in Each Phase |

|---|

| Phase 1 |

| What was the impact of COVID-19 on your specific place of work, so far, in relation to patient numbers and service demand? If your caring responsibilities have changed during the COVID-19 Pandemic, can you say more about this? Can you describe what employer supports have worked well during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Can you describe what other support from your employer would have helped you in your day-to-day job during the COVID-19 Pandemic? What do you think employers need to provide to support their staff during any future Pandemics? What do you think employers need to do to support their staff in normal service delivery periods, that have been learned during the COVID-19 Pandemic |

| Phase 2 |

| What was the impact of COVID-19 on your specific place of work, so far, in relation to patient/service user numbers and service demand since July 2020? Can you describe what employer supports have worked well during the COVID-19 Pandemic and what could be improved? Is there anything else you would like to share with us about working in health and social care during the COVID-19 Pandemic? |

| Phase 3 |

| Between February and June 2021, what was the impact of COVID-19 on your specific place of work, in relation to patient/service user numbers and service demand? How did the experience of the pandemic change the way you now manage work and non-work responsibilities? |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2022. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Serafini, G.; Parmigiani, B.; Amerio, A.; Aguglia, A.; Sher, L.; Amore, M. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health in the General Population. QJM Int. J. Med. 2020, 113, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holton, S.; Wynter, K.; Rothmann, M.J.; Skjøth, M.M.; Considine, J.; Street, M.; Hutchinson, A.F.; Khaw, D.; Hutchinson, A.M.; Ockerby, C.; et al. Australian and Danish Nurses’ and Midwives’ Wellbeing during COVID-19: A Comparison Study. Collegian 2022, 29, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kock, J.H.; Latham, H.A.; Leslie, S.J.; Grindle, M.; Munoz, S.; Ellis, L.; Polson, R.; O’Malley, C.M. A Rapid Review of the Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers: Implications for Supporting Psychological Well-Being. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper, K.; Murrells, T.; Sanders, J.; Anderson, J.E.; Blake, H.; Kelly, D.; Kent, B.; Maben, J.; Rafferty, A.M.; Taylor, R.M.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Wellbeing of the UK Nursing and Midwifery Workforce during the First Pandemic Wave: A Longitudinal Survey Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 127, 104155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillen, P.; Neill, R.D.; Manthorpe, J.; Mallett, J.; Schroder, H.; Nicholl, P.; Currie, D.; Moriarty, J.; Ravalier, J.; McGrory, S. Decreasing Wellbeing and Increasing use of Negative Coping Strategies: The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the UK Health and Social Care Workforce. Epidemiologia 2022, 3, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.M.; Matthai, M.T.; Budhathoki, C. Midwifery Professional Stress and its Sources: A Mixed-methods Study. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2018, 63, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvie, K.; Sidebotham, M.; Fenwick, J. Australian Midwives’ Intentions to Leave the Profession and the Reasons Why. Women Birth 2019, 32, e584–e593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, B.; Fenwick, J.; Sidebotham, M.; Henley, J. Midwives in the United Kingdom: Levels of Burnout, Depression, Anxiety and Stress and Associated Predictors. Midwifery 2019, 79, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCM. RCM Warns of Midwife Exodus as Maternity Staffing Crisis Grows. 2021. Available online: https://www.rcm.org.uk/media-releases/2021/september/rcm-warns-of-midwife-exodus-as-maternity-staffing-crisis-grows/ (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Yörük, S.; Güler, D. The Relationship between Psychological Resilience, Burnout, Stress, and Sociodemographic Factors with Depression in Nurses and Midwives during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study in Turkey. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagen-Torkko, M.; Altman, M.R.; Kantrowitz-Gordon, I.; Gavin, A.; Mohammed, S. Moral Distress, Trauma, and Uncertainty for Midwives Practicing during a Pandemic. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2021, 66, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, S.; Maude, R.; Zhao, I.Y.; Bradford, B.; Gilkison, A. New Zealand Maternity and Midwifery Services and the COVID-19 Response: A Systematic Scoping Review. Women Birth 2021, 35, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hearn, F.; Biggs, L.; Wallace, H.; Riggs, E. No One Asked Us: Understanding the Lived Experiences of Midwives Providing Care in the North West Suburbs of Melbourne during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Interpretive Phenomenology. Women Birth 2021, 35, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stulz, V.M.; Bradfield, Z.; Cummins, A.; Catling, C.; Sweet, L.; McInnes, R.; McLaughlin, K.; Taylor, J.; Hartz, D.; Sheehan, A. Midwives Providing Woman-Centred Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia: A National Qualitative Study. Women Birth 2021, 35, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S.; Chan, V. Lessons from Past Epidemics and Pandemics and a Way Forward for Pregnant Women, Midwives and Nurses during COVID-19 and Beyond: A Meta-Synthesis. Midwifery 2020, 90, 102821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnuaimi, K. Understanding Jordanian Midwives’ Experiences of Providing Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis: A Phenomenological Study. Int. J. Commun. Based Nurs. Midwifery 2021, 9, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazfiarini, A.; Akter, S.; Homer, C.S.E.; Zahroh, R.I.; Bohren, M.A. ‘We are Going into Battle without Appropriate Armour’: A Qualitative Study of Indonesian Midwives’ Experiences in Providing Maternity Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Women Birth 2021, 35, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L. College Survey Confirms the Impact of COVID Response on Midwives. Aotearoa N. Z. Midwife 2020, 96, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- González-Timoneda, A.; Hernández Hernández, V.; Pardo Moya, S.; Alfaro Blazquez, R. Experiences and Attitudes of Midwives during the Birth of a Pregnant Woman with COVID-19 Infection: A Qualitative Study. Women Birth 2021, 34, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradfield, Z.; Hauck, Y.; Homer, C.S.E.; Sweet, L.; Wilson, A.N.; Szabo, R.A.; Wynter, K.; Vasilevski, V.; Kuliukas, L. Midwives’ Experiences of Providing Maternity Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia. Women Birth 2021, 35, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçüktürkmen, B.; Baskaya, Y.; Özdemir, K. A Qualitative Study of Turkish Midwives’ Experience of Providing Care to Pregnant Women Infected with COVID-19. Midwifery 2022, 105, 103206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinsky, S.E.; Adhikari, N.K. COVID-19, Variants of Concern and Pregnancy Outcome. Obstet. Med. 2021, 14, 65–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradfield, Z.; Wynter, K.; Hauck, Y.; Vasilevski, V.; Kuliukas, L.; Wilson, A.N.; Szabo, R.A.; Homer, C.S.E.; Sweet, L. Experiences of Receiving and Providing Maternity Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia: A Five-Cohort Cross-Sectional Comparison. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.N.; Sweet, L.; Vasilevski, V.; Hauck, Y.; Wynter, K.; Kuliukas, L.; Szabo, R.A.; Homer, C.S.; Bradfield, Z. Australian Women’s Experiences of Receiving Maternity Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional National Survey. Birth 2021, 49, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemperle, M.; Grylka-Baeschlin, S.; Klamroth-Marganska, V.; Ballmer, T.; Gantschnig, B.E.; Pehlke-Milde, J. Midwives’ Perception of Advantages of Health Care at a Distance during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Switzerland. Midwifery 2022, 105, 103201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCT. Birth Partners and Coronavirus. 2021. Available online: https://www.nct.org.uk/labour-birth/coronavirus-and-birth/birth-partners-and-coronavirus (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Vasilevski, V.; Sweet, L.; Bradfield, Z.; Wilson, A.N.; Hauck, Y.; Kuliukas, L.; Homer, C.S.E.; Szabo, R.A.; Wynter, K. Receiving Maternity Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences of Women’s Partners and Support Persons. Women Birth 2021, 35, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtala, H.; Parzefall, M.R. Promotion of employee wellbeing and innovativeness: An opportunity for a mutual benefit. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2007, 16, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. The Job Demands–Resources Model: Challenges for Future Research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Role of Personal Resources in the Job Demands-Resources Model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, P.; Gillen, P.; Moriarty, J.; Schroder, H.; Mallett, J.; Ravalier, J.; Manthorpe, J.; Currie, D.; Nicholl, P.; McGrory, S.; et al. Health and Social Care Workers’ Quality of Working Life and Coping while Working during the COVID19 Pandemic: Findings from a UK Survey, Phase 3: 10th May 2021–5th July 2021. Ulster UniversityUlster University. 2021. Available online: https://www.hscworkforcestudy.co.uk/_files/ugd/2749ea_33ce52835941457db39e61badc9fa989.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- NHS Scotland. WEMWBS-User-Guide 2008. Available online: http://www.ocagingservicescollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/WEMWBS-User-Guide-Version-1-June-2008.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis, a Practical Guide; Sage: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Boulton, E.; Davey, L.; McEvoy, C. The Online Survey as a Qualitative Research Tool. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 24, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavadra, B.; Stockl, A.; Prosser-Snelling, E.; Simpson, P.; Morris, E. Women’s Perceptions of COVID-19 and their Healthcare Experiences: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis of a National Survey of Pregnant Women in the United Kingdom. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semaan, A.; Audet, C.; Huysmans, E.; Afolabi, B.; Assarag, B.; Banke-Thomas, A.; Blencowe, H.; Caluwaerts, S.; Campbell, O.M.R.; Cavallaro, F.L. Voices from the Frontline: Findings from a Thematic Analysis of a Rapid Online Global Survey of Maternal and Newborn Health Professionals Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ockenden, D. Findings, Conclusions and Essential Actions from the Independent Review of Maternity Services at the Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust. 2022. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1064302/Final-Ockenden-Report-web-accessible.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- NHS Digital. NHS Workforce Statistics-April 2021. 2021. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-workforce-statistics/april-2021# (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Goberna-Tricas, J.; Biurrun-Garrido, A.; Perelló-Iñiguez, C.; Rodríguez-Garrido, P. The COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: Experiences of Midwives on the Healthcare Frontline. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; de Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 2020, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G.; Teoh, K.; Harriss, A. The Mental Health and Wellbeing of Nurses and Midwives in the United Kingdom. 2020, pp. 1–68. Available online: https://www.som.org.uk/sites/som.org.uk/files/The_Mental_Health_and_Wellbeing_of_Nurses_and_Midwives_in_the_United_Kingdom.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Walton, G. COVID-19. The New Normal for Midwives, Women and Families. Midwifery 2022, 87, 102736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, T.; Muurlink, O.; Williamson, M. Social Culture and the Bullying of Midwifery Students Whilst on Clinical Placement: A Qualitative Descriptive Exploration. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 52, 103045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen Patricia, A.; Sincair, M.; Kernohan, G. The Nature and Manifestations of Bullying in Midwifery; Ulster University: Coleraine, UK, 2008; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, Y.E.; Koçak, V. Psychological effects of nurses and midwives due to COVID-19 outbreak: The case of Turkey. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 34, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewska, B.; Barratt, I.; Townsend, R.; Kalafat, E.; van der Meulen, J.; Gurol-Urganci, I.; O’Brien, P.; Morris, E.; Draycott, T.; Thangaratinam, S.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e759–e772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Patient Safety: A Rapid Review; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240055094 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Asefa, A.; Semaan, A.; Delvaux, T.; Huysmans, E.; Galle, A.; Sacks, E.; Bohren, M.A.; Morgan, A.; Sadler, M.; Vedam, S.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the provision of respectful maternity care: Findings from a global survey of health workers. Women Birth 2022, 35, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, I.H.M.; Thompson, A.; Dunlop, C.L.; Wilson, A. Midwives’ and maternity support workers’ perceptions of the impact of the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic on respectful maternity care in a diverse region of the UK: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e064731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, L.; Griffiths, P.; Kitson-Reynolds, E. Midwifery and nurse staffing of inpatient maternity services–a systematic scoping review of associations with outcomes and quality of care. Midwifery 2021, 103, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, E.; Hunter, B. Relationships between working conditions and emotional wellbeing in midwives. Women Birth 2019, 32, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Midwives. Caring for You Campaign: Survey Results. RCM Campaign for Healthy Workplaces Delivering High Quality Care; RCM: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.rcm.org.uk/media/2899/caring-for-you-working-in-partnership-rcm-campaign-for-healthy-workplaces-delivering-high-quality-care.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Z. Cross-Sectional Studies: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Recommendations. Chest 2020, 158, S65–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Phase 1 (7 May–3 July 2020) | Phase 2 (17 November 2020–1 February 2021) | Phase 3 (10 May–2 July 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 180 (100%) | 75 (100%) | 169 (98.8%) |

| Age | |||

| 16–29 | 27 (15.0%) | 5 (6.7%) | 29 (17.0%) |

| 30–39 | 38 (21.1%) | 16 (21.3%) | 45 (26.3%) |

| 40–49 | 57 (31.7%) | 23 (30.7%) | 49 (28.7%) |

| 50–59 | 44 (24.4%) | 28 (37.3%) | 36 (21.1%) |

| 60–65 | 14 (7.8%) | 3 (4.0%) | 12 (7.0%) |

| Ethnic background | |||

| White | 174 (96.7%) | 75 (100%) | 165 (96.5%) |

| Black | 2 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.8%) |

| Asian | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mixed | 3 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.8%) |

| Country of work | |||

| England | 41 (22.8%) | 5 (6.7%) | 77 (45.0%) |

| Scotland | 5 (2.8%) | 5 (6.7%) | 17 (9.9%) |

| Wales | 53 (29.4%) | 1 (1.3%) | 47 (27.5%) |

| Northern Ireland | 81 (45.0%) | 64 (85.3%) | 30 (17.5%) |

| Number of years of work experience | |||

| Less than 2 years | 12 (6.7%) | 2 (2.7%) | 18 (10.6%) |

| 2–5 years | 20 (11.1%) | 6 (8.0%) | 29 (17.1%) |

| 6–10 years | 34 (18.9%) | 8 (10.7%) | 35 (20.6%) |

| 11–20 years | 39 (21.9%) | 17 (22.7%) | 33 (19.4%) |

| 21–30 years | 37 (20.8%) | 19 (25.3%) | 16 (9.4%) |

| More than 30 years | 36 (20.2%) | 23 (30.7%) | 39 (22.9%) |

| Place of work | |||

| Hospital | 113 (62.8%) | 48 (64.0%) | 107 (62.6%) |

| Community | 36 (20.0%) | 17 (22.7%) | 47 (27.5%) |

| General practice (GP) based | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 5 (2.9%) |

| Other | 31 (17.2%) | 9 (12.0%) | 12 (7.0%) |

| Disability status | |||

| Yes | 12 (7.1%) | 6 (8.8%) | 8 (5.3%) |

| No | 156 (92.9%) | 68 (91.2%) | 142 (94.0%) |

| Unsure | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Themes | Relentless Stress/Pressure | Reconfiguration of Services | Protection of Self and Others | Workforce Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subthemes | Work practices Client related | Ante/post-natal, homebirth, home visits changes Impact of closure/changes to other services Additional workload | PPE Home/work balance Protection of family Importance of practical and emotional support | Staffing Management and leadership Communication Inequity Feeling valued data |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGrory, S.; Neill, R.D.; Gillen, P.; McFadden, P.; Manthorpe, J.; Ravalier, J.; Mallett, J.; Schroder, H.; Currie, D.; Moriarty, J.; et al. Self-Reported Experiences of Midwives Working in the UK across Three Phases during COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013000

McGrory S, Neill RD, Gillen P, McFadden P, Manthorpe J, Ravalier J, Mallett J, Schroder H, Currie D, Moriarty J, et al. Self-Reported Experiences of Midwives Working in the UK across Three Phases during COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013000

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGrory, Susan, Ruth D. Neill, Patricia Gillen, Paula McFadden, Jill Manthorpe, Jermaine Ravalier, John Mallett, Heike Schroder, Denise Currie, John Moriarty, and et al. 2022. "Self-Reported Experiences of Midwives Working in the UK across Three Phases during COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013000

APA StyleMcGrory, S., Neill, R. D., Gillen, P., McFadden, P., Manthorpe, J., Ravalier, J., Mallett, J., Schroder, H., Currie, D., Moriarty, J., & Nicholl, P. (2022). Self-Reported Experiences of Midwives Working in the UK across Three Phases during COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013000