Social, Economic and Human Capital: Risk or Protective Factors in Sexual Violence?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Sexual Violence

2.2.2. Social, Economic and Human Capital

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis Prevalence of Sexual Aggression

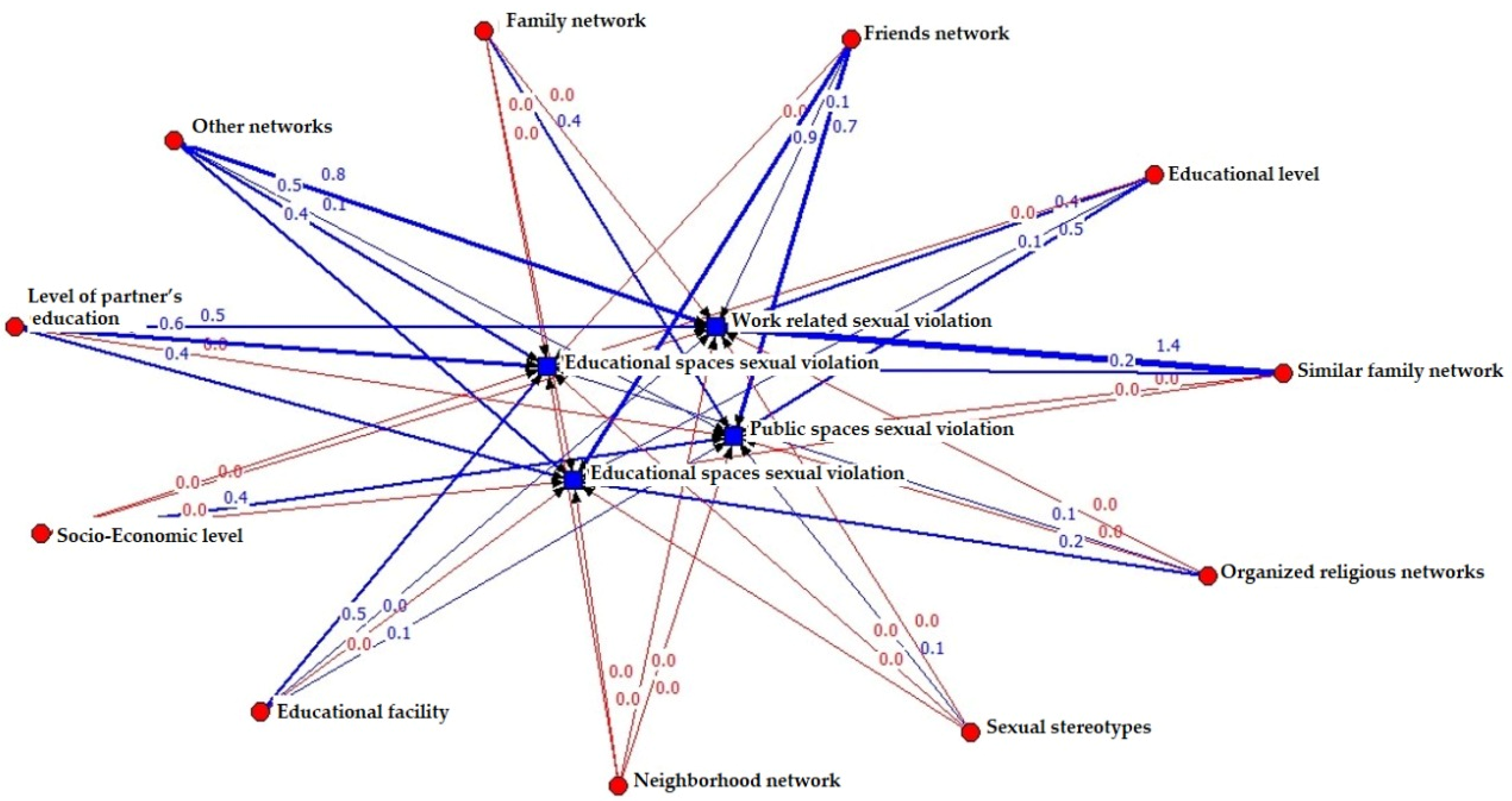

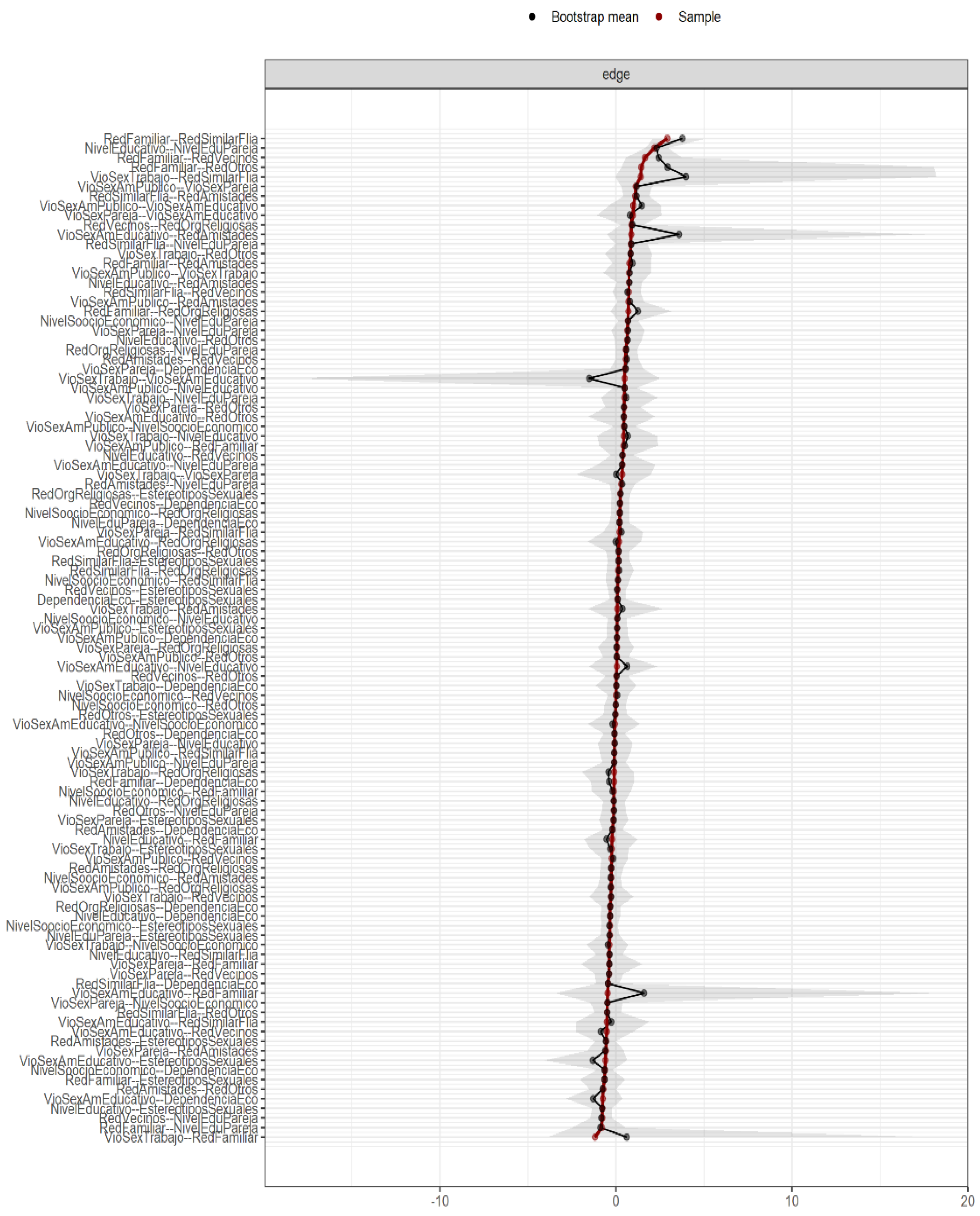

3.2. Definition of the Neural Network

3.3. Lattice Analysis

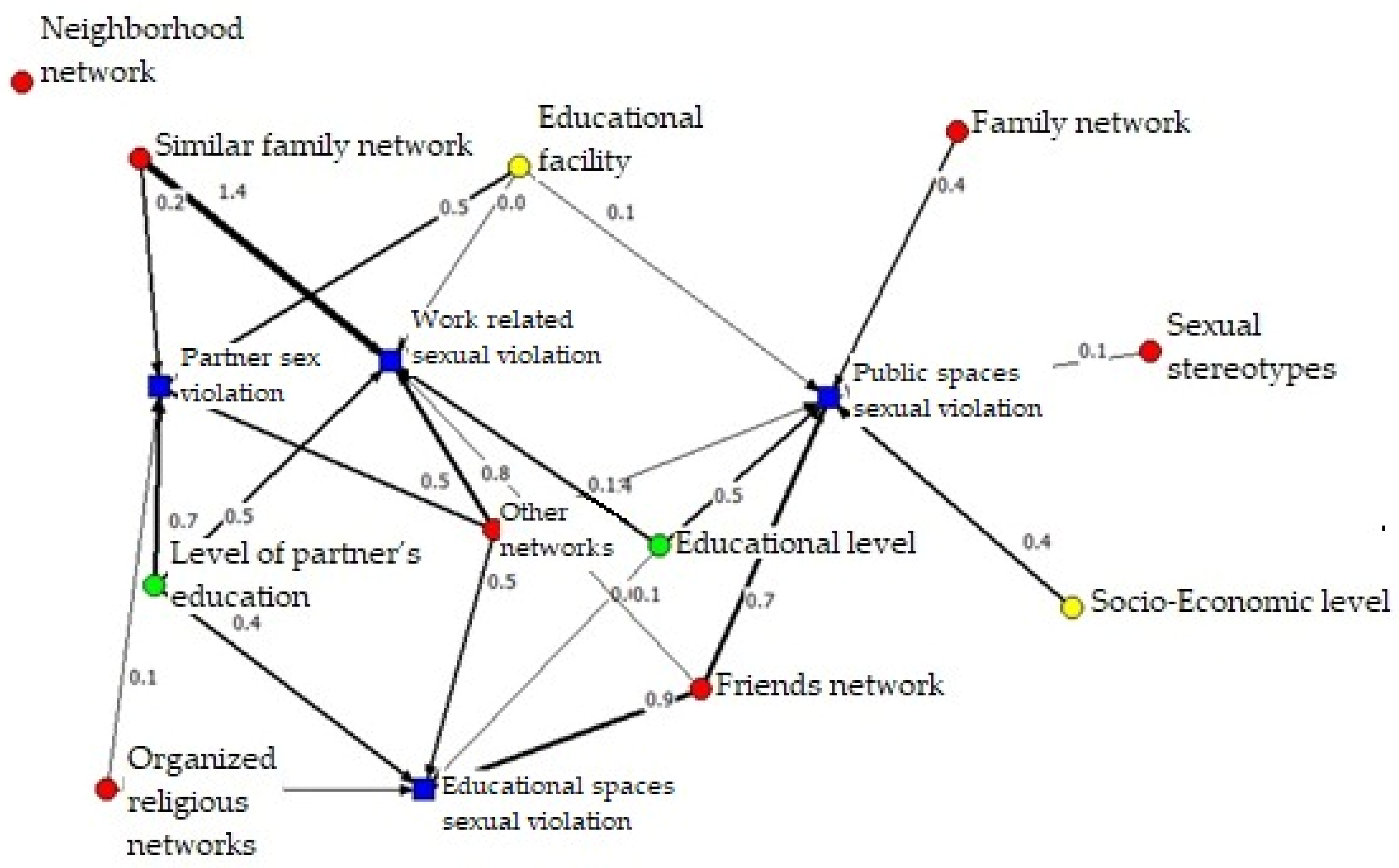

3.3.1. Protective Networks

3.3.2. Risk Networks

4. Discussion

4.1. Social, Economic and Human Capital as a Protective Effect for Sexual Violence

4.2. Social, Human and Economic Capital as Risk Factors in Sexual Victimization

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Un Women. Definition of Sexual Assault and Other Elements. Available online:https://www.endvawnow.org/en/articles/453-definition-of-sexual-assault-and-other-elements.html (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Estudio Revela Que en Chile SE Cometen 17 Violaciones Diarias Y 34 Abusos Sexuales Emol.com. Available online: https://www.emol.com/noticias/nacional/2011/09/23/504699/analisis-revela-que-en-chile-se-cometen-17-violaciones-diarias-y-34-abusos-sexuales.html (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Informe Estadístico de la FiscalíA: Denuncias de Delitos Crecieron Un 4.37% En El año 2018. Fiscalía de Chile. Available online: http://www.fiscaliadechile.cl/Fiscalia/sala_prensa/noticias_det.do?id=15644 (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Krug, E.G.; Mercy, J.A.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Zwi, A.B. World report on violence and health. Lancet 2002, 360, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickert, V.I.; Vaughan, R.D.; Wiemann, C.M. Adolescent dating violence and date rape. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 14, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COmprender Y Abordar la Violencia Contra Las Mujeres. Violencia Sexual. Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2013. WHO/RHR/12.37. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/98821/WHO_RHR_12.37_spa.pdf;sequence=1 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Lopez, S. The prevention of gender-based violence at the European Union. A 75 years journey. Perspect. Rev. De Cienc. Soc. 2020, 5, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, N.; Devries, K.; Watts, C.; Pallitto, C.; Petzol, M.; Shamu, S.; Garcia-Morena, C. Worldwide Prevalence of Non-Partner Sexual Violence: A Systematic Review. Lancet 2014, 383, 1648–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Internacional del Trabajo. Global Estimates of Modern Slavery. Oit.org. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_575479/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Chaparro, A. Acoso y hostigamiento sexual: Una revisión conceptual a partir de #MeToo. Rev. Investig. Divulg. Sobre Estud. Género 2021, 29, 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hooton, C. Netflix Film Crews ‘Banned from Looking at Each Other for Longer than Five Seconds’ in #Metoo Crackdown. Independent.co.uk. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/tv/news/netflix-sexual-harassment-training-rules-me-too-flirtingon-set-a8396431.html (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Lisak, D.; Miller, P.M. Repeat Rape and Multiple Offending Among Undetected Rapists. Violence Vict. 2002, 17, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, M.; Lussier, P. Estimating the size of the sexual aggressor population. In Sex Offenders: A Criminal Career Approach; Blokland, A., Lussier, P., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Drury, A.; Elbert, M.; Delisi, M. The dark figure of sexual offending: A replication and extension. Behavior. Sci. Law 2020, 38, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, J.A.; Lehrer, E.L.; Koss, M.P. Unwanted sexual experiences in young men: Evidence from a survey of university students in Chile. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2013, 42, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ilabaca, P.; Fuertes, A.; Orgaz, B. Impacto de la Coerción Sexual en la Salud Mental y Actitud Hacia la Sexualidad: Un Estudio Comparativo Entre Bolivia, Chile y España. Psykhe 2015, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, I.; Krahé, B.; Ilabaca Baeza, P.; Muñoz-Reyes, J.A. Sexual Aggression Victimization and Perpetration among Male and Female College Students in Chile. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, V.L.; Ward, S.; Cohn, E.S.; Plante, E.G.; Moorhead, C.; Walsh, W. Unwanted Sexual Contact on Campus: A Comparison of Women’s and Men’s Experiences. Violence Vict. 2007, 22, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, J.A.; Lehrer, V.L.; Lehrer, E.L.; Oyarzun, P. Sexual violence in college students in Chile. In IZA Discussion Papers (No. 3133); Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, C.D.; Robinson, A.L.; Post, L.A. The nature and predictors of sexual victimization and offending among adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2003, 32, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösel, F.; Farrington, D.P. Direct protective and buffering protective factors in the development of youth violence. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43 (Suppl. S1), S8–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, K.C.; Hamburger, M.E.; Swahn, M.H.; Choi, C. Sexual violence perpetration by adolescents in dating versus same-sex peer relationships: Differences in associated risk and protective factors. West J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 14, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, L.F.; Swartout, K.M.; Swahn, M.H.; Bellis, A.L.; Carney, J.; Vagi, K.J.; Lokey, C. Precollege sexual violence perpetration and associated risk and protective factors among male college freshmen in Georgia. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 62, S51–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowsky, I.W.; Hogan, M.; Ireland, M. Adolescent sexual aggression: Risk and protective factors. Pediatrics 1997, 100, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, C.G.; Trinitapoli, J.A.; Anderson, K.L.; Johnson, B.R. Race/ ethnicity, religious involvement, and domestic violence. Violence Against Women 2007, 13, 1094–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, C.G.; Anderson, K.L. Religious involvement and domestic violence among U.S. couples. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2001, 40, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, C.G.; Bartkowski, J.P.; Anderson, K.L. Are there religious variations in domestic violence? J. Fam. Issues 1999, 20, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Horne, S.G.; Levitt, H.M.; Klesges, L.M. Christian women in IPV relationships: An exploratory study of religious factors. J. Psychol. Christ. 2009, 28, 224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bonar, E.E.; DeGue, S.; Abbey, A.; Coker, A.L.; Lindquist, C.H.; McCauley, H.L.; Miller, E.; Senn, C.Y.; Thompson, M.P.; Ngo, Q.M. Prevention of sexual violence among college students: Current challenges and future directions. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, M.C.; D’Inverno, A.S.; Reidy, D.E. The Association Between Gender Inequality and Sexual Violence in the U.S. Am. J Prev. Med. 2020, 58, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, C.R. The span of collective efficacy: Extending social disorganization theory to partner violence. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 833–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, K.; Wallis, A.B.; Hamberger, L.K. Neighborhood environment and intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2015, 16, 16–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.J.; Bolton, P.A.; Annan, J.; Kaysen, D.; Robinette, K.; Cetinoglu, T.; Wachter, K.; Bass, J.K. The effect of cognitive therapy on structural social capital: Results from a randomized controlled trial among sexual violence survivors in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1680–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D.; Feldstein, L. Better Together: Restoring the American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Uphoff, N. Understanding Social Capital: Learning from the Analysis and Experience of Participation. In Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Lozares, C.; Verd Pericàs, J.M.; Martí, J.; López-Roldán, P.; Molina, J.L. Cohesión, Vinculación e Integración sociales en el marco del Capital Social. Redes Rev Hisp Para Anál Redes Soc. 2011, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotor, A.J.; Runyan, D.K. Social capital, family violence, and neglect. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e1124–e1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larance, L.Y.; Porter, M.L. Observations from practice: Support group membership as a process of social capital formation among female survivors of domestic violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2004, 19, 676–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutter, M. Do Women Suffer from Network Closure? The Moderating Effect of Social Capital on Gender Inequality in a Project-Based Labor Market, 1929 to 2010. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 80, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Emmerik, H. Gender differences in the creation of different types of social capital: A multilevel study. Soc. Netw. 2006, 28, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Ökonomisches Kapital, Kulturelles Kapital, Soziales Kapital; Kreckel, R., Ed.; Soziale Ungleichheiten, Soziale Welt; Otto Schwartz: Göttingen, Germany, 1983; Volume 2, pp. 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Abarzúa, I.N. Capital Humano: Su Definición y Alcances en el Desarrollo Local y Regional. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2005, 13, 1–36. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?idp=1&id=275020513035&cid=15097 (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Dalal, K.; Rahman, F.; Jansson, B. Wife abuse in rural Bangladesh. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2009, 41, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, F.; Barrientos, J.; Guzmán, M.; Cárdenas, M.; Bahamondes, J. Violencia de pareja en hombres gay y mujeres lesbianas chilenas: Un estudio exploratorio. Interdisciplinaria 2017, 34, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.R.C.; da Silva, A.A.M.; de Britto e Alves, M.T.S.S.; Batista RF, L.; Ribeiro CC, C.; Schraiber, L.B.; Bettiol, H.; Barbieri, M.A. Effects of socioeconomic status and social support on violence against pregnant women: A structural equation modeling analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M.W.; Edwards, B. Editors’ introduction: Escape from politics? Social theory and the social capital debate. Am. Behav. Sci. 1997, 40, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, M. Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory Soc. 1998, 27, 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B.J.; St Pierre, M. Intimate partner violence reported by lesbian-, gay-, and bisexual-identified individuals living in Canada: An exploration of within-group variations. J. Gay. Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2013, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, D.; Hilario, V.; Mejia, D. Perú: Indicadores de Violencia Familiar Y Sexual, 2000–2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1465/libro.Pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- International Youth Day 2013. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/unesco/events/prizes-and-celebrations/celebrations/international-days/international-youth-day-2013/ (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Instituto Nacional de la Juventud. Las Claves en la Disminución de Jóvenes Que No Estudian Y SE Encuentran Laboralmente Inactivos; Injuv: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2017.

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossakowski, J.J.; Epskamp, S.; Kieffer, J.M.; van Borkulo, C.D.; Rhemtulla, M.; Borsboom, D. The application of a network approach to Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL): Introducing a new method for assessing HRQoL in healthy adults and cancer patients. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics 2008, 9, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S. IsingSampler: Sampling Methods and Distribution Functions for the Ising Model. 2014. Available online: github.com/SachaEpskamp/IsingSampler (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Van Borkulo, C.D.; Borsboom, D.; Epskamp, S.; Blanken, T.F.; Boschloo, L.; Schoevers, R.A.; Waldorp, L.J. A new method for constructing networks from binary data. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foygel, R.; Drton, M. Extended Bayesian Information Criteria for Gaussian Graphical Models. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1011.6640. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1011.6640 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Lauritzen, S.L.; Wermuth, N. Graphical Models for Associations Between Variables, Some of which are Qualitative and Some Quantitative. Ann. Stat. 1989, 17, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinshausen, N.; Bühlmann, P. High-dimensional graphs and variable selection with the Lasso. Ann. Stat. 2006, 34, 1436–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanneman, R.; Riddle, M. Introduction to Social Network Methods, Riverside, 2005, University of California. Available online: http://www.faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Fruchterman, T.; Reingold, E. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw. —Pract. Exp. 1991, 21, 1129–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M.; Foran, H.M.; Heyman, R.E. United States Air Force Family Advocacy Research Program. An ecological model of intimate partner violence perpetration at different levels of severity. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voith, L.A. Understanding the relation between neighborhoods and intimate partner violence: An integrative review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2019, 20, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M.A.; Goycolea, R.; Santos, T. Convivencia, disciplina y conflicto: Las Secciones Juveniles de las cárceles de adultos en Gendarmería de Chile. Análisis de las actas de la Comisión Interinstitucional de Supervisión de los Centros de Privación de Libertad (2014–2017). Política Crim. 2020, 15, 141–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerna, T.; Molina, T. Aggression against Defendants in Santiago 1: The Harsh “Codes” among Inmates in Chile’s Prisons. Available online: https://www.emol.com/noticias/Nacional/2018/06/22/910720/Agresion-a-reclusos-de-Santiago-1-Los-codigos-que-se-manejan-en-carceles-para-hacer-pagar-a-algunos-reclusos.html (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Ketterer Romero, L.M.; Mayorga Muñoz, C.; Carrasco Henríquez, M.; Soto Higueras, A.; Tragolaf Ancalaf, A.; Nitrihual, L.; del Valle, C. Modelo participativo para el abordaje de la violencia contra las mujeres en La Araucanía, Chile. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2017, 41, e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Campo, P.; Burke, J.; Peak, G.L.; McDonnell, K.A.; Gielen, A.C. Uncovering neighbourhood influences on intimate partner violence using concept mapping. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, B.; O´neal, E.; Hernandez, C. The Sexual Victimization of College Students: A Test of Routine Activity Theory. Crime Delinq. 2021, 67, 2043–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzetti, C.M. Economic Stress and Domestic Violence; VAWnet, a Project of the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence; National Resource Center on Domestic Violence: Harrisburg, PA, USA, 2021; Available online: http://www.vawnet.org (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Putnam, R.D. The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life. Am. Prospect. 1993, 13, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.; Jovchelovitch, S. Health, community and development: Towards a social psychology of participation. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 10, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.M. The relationship between social support and intimate partner violence in neighborhood context. Crime Delinq. 2015, 61, 1333–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, E. Adolescencia y familia: Revisión de la relación y la comunicación como factores de riesgo o protección. Rev. Intercont. De Psicol. Y Educ. 2008, 10, 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tharp, A.T.; DeGue, S.; Valle, L.A.; Brookmeyer, K.A.; Massetti, G.M.; Matjasko, J.L. A systematic qualitative review of risk and protective factors for sexual violence perpetration. Trauma Violence Abus. 2013, 14, 133–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomi, A.; Nichols, E.; Kammes, R.; Green, T. Sexual Violence and Intimate Partner Violence in College Women with a Mental Health and/or Behavior Disability. J. Women’s Health 2018, 27, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouriles, E.N.; McDonald, R. Intimate partner violence, coercive control, and child adjustment problems. J. Interpers. Violence 2015, 30, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamu, S.; Shamu, P.; Machisa, M. Factors associated with past year physical and sexual intimate partner violence against women in Zimbabwe: Results from a national cluster-based cross-sectional survey. Glob Health Action. 2018, 11 (Suppl. S3), 1625594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, H.L.M.; Foshee, V.A.; Niolon, P.H.; Reidy, D.E.; Hall, J.E. Gender role attitudes and male adolescent dating violence perpetration: Normative beliefs as moderators. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCauley, H.L.; Tancredi, D.J.; Silverman, J.G.; Decker, M.R.; Austin, S.B.; McCormick, M.C.; Virata, M.C.; Miller, E. Gender-equitable attitudes, bystander behavior, and recent abuse perpetration against heterosexual dating partners of male high school athletes. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1882–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Family Map. Mapping Family Change and Child Well-Being Outcomes. 2019. Available online: https://ifstudies.org/ifs-admin/resources/reports/worldfamilymap-2019-051819.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Valenzuela, E.; Odgers, O. Usos sociales de la religión como recurso ante la violencia: Católicos, evangélicos y testigos de Jehová en Tijuana, México. Culturales 2014, 2, 9–40. [Google Scholar]

- Perusset, M. Las redes sociales interpersonales y la violencia de género. Tareas 2019, 163, 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lanier, C.; Maume, M.O. Intimate partner violence and social isolation across the rural/urban divide. Violence Against Women 2009, 15, 1311–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Trujillo, M.; Jaramillo-Sierra, A.L.; Quintane, E. Connectedness as a protective factor of sexual victimization among university students. Vict. Offender. 2019, 14, 895–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammert, L. La relación entre confianza e inseguridad: El caso de Chile. Rev. Crim. 2014, 56, 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- RuizPerez, I.; Pastor-Moreno, G. Medidas de contención de la violencia de género durante la pandemia de COVID-19Measures to contain gender-based violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gac. Sanit. 2020, 35, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Menés, J.; Puig, D.; Sobrino, C. Polyand distinct-victimization in histories of violence against women. J. Fam. Violence 2014, 29, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Moreno, C.; Jansen, H.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet 2006, 368, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthman, O.A.; Lawoko, S.; Moradi, T. Factors associated with attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women: A comparative analysis of 17 sub-Saharan countries. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2009, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M.A.; Gelles, R.J.; Steinmetz, S. Behind Closed Doors: Violence in the American Family; SAGE Publications: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- León, T.; Grez, M.; Prato, J.; Torres, R.; Ruiz, S. Violencia intrafamiliar en Chile y su impacto en la salud: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Med. Chil. 2014, 142, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ceballo, R.; Ramirez, C.; Castillo, M.; Caballero, G.A.; Lozoff, B. Domestic violence and women’s mental health in Chile. Psychol. Women Q. 2004, 28, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhirter, P.T. La violencia privada: Domestic violence in Chile. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 15 to 19 years | 384 | 23.1 |

| 20 to 25 years | 656 | 39.4 |

| 26 to 30 years | 625 | 37.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 1496 | 89.8 |

| Married | 138 | 8.3 |

| Civil union | 15 | 0.9 |

| Separated | 9 | 0.5 |

| Divorced | 5 | 0.3 |

| Widowed | 2 | 0.1 |

| Educational level | ||

| No studies | 2 | 0.1 |

| Grade school | 84 | 5.0 |

| Secondary school | 792 | 47.6 |

| Technical professional | 273 | 16.4 |

| University education | 506 | 30.4 |

| Post-graduate studies | 6 | 0.4 |

| Socio-economic level | ||

| High | 128 | 7.7 |

| Medium | 688 | 41.3 |

| Low | 849 | 51.0 |

| Variable | Never | Once Per Week | Once Per Month | Once Per Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| How often do you see or communicate with…? | ||||

| Immediate family | 1.9 (32) | 90.2 (1502) | 5.3 (88) | 2.4 (40) |

| People I consider family | 7.7 (129) | 77.7 (1293) | 12.1 (202) | 2.1 (35) |

| Friends | 6.6 (110) | 73.8 (1228) | 16.5 (275) | 2.8 (47) |

| Neighbors | 24.1 (401) | 55.3 (921) | 15.6 (259) | 4.9 (81) |

| Religious communities | 69 (1149) | 14.4 (239) | 6.6 (110) | 9.6 (160) |

| Others | 75.7 (1260) | 9.3 (155) | 3.5 (58) | 1.2 (20) |

| Variable | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Indifferent | In Agreement | Totally Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| It is more appropriate for the man to be recognized as the head of the household. | 29.2 (485) | 48.8 (809) | 6.8 (113) | 12.2 (203) | 2.9 (49) |

| Men should be responsible for family and household expenses. | 25 (414) | 43 (713) | 6.4 (106) | 19.7 (326) | 6 (100) |

| Women should be responsible for the care of children instead of men. | 30.1 (500) | 51.9 (862) | 5.4 (89) | 9.9 (165) | 2.7 (45) |

| Doing household chores (cleaning, washing, ironing, cooking) is a task more suitable for women than for men. | 36.4 (604) | 51.3 (852) | 4.5 (75) | 5.9 (98) | 1.9 (31) |

| A wife/partner should not contradict her husband’s/partner’s opinion. | 39.9 (662) | 49.4 (819) | 3.4 (57) | 5.8 (97) | 1.4 (24) |

| A woman may participate in a social activity, even if she does not have her husband’s/partner’s approval. | 5.5 (91) | 11.7 (193) | 2.2 (37) | 43.3 (716) | 37.3 (618) |

| A woman can choose her friends, even if her husband does not like it. | 3.9 (65) | 7.6 (125) | 1.8 (30) | 44.7 (740) | 42 (694) |

| A woman’s dress and make-up must be approved by her husband/partner. | 38.8 (645) | 52.5 (873) | 2.6 (43) | 4.5 (74) | 1.6 (27) |

| A woman should have sexual relations with her husband/partner, even if she does not want to. | 52.4 (869) | 45.5 (755) | 1 (16) | 1 (16) | 0.2 (3) |

| A woman should avoid dressing provocatively in order to avoid harassment. | 37.1 (615) | 48.2 (799) | 3.5 (58) | 8.5 (141) | 2.8 (46) |

| Women should accept abuse for the sake of the family and their children. | 53.6 (891) | 44.6 (740) | 0.8 (13) | 0.9 (15) | 0.1 (2) |

| If there are blows or mistreatment in the house, it is a matter to be solved in the family. | 35.3 (580) | 40.2 (660) | 3.4 (56) | 17.5 (287) | 3.7 (60) |

| It is acceptable for a man to assault his partner in case of infidelity. | 55.4 (921) | 43.3 (719) | 0.8 (13) | 0.4 (6) | 0.2 (3) |

| Variables | Sexual Violation in Public Spaces | in Work Spaces | in Partnerships | in Educational Spaces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-economic level | 0.448 | −0.372 | −0.483 | −0.057 |

| Educational level | 0.485 | 0.441 | −0.081 | 0.049 |

| Family networks | 0.426 | −1.191 | −0.384 | −0.472 |

| Family similar networks | −0.092 | 1.411 | 0.206 | −0.517 |

| Friend networks | 0.713 | 0.078 | −0.567 | 0.866 |

| Neighborhood networks | −0.244 | −0.289 | −0.392 | −0.518 |

| Religious org. networks | −0.275 | −0.101 | 0.058 | 0.176 |

| Other networks | 0.051 | 0.822 | 0.464 | 0.454 |

| Partner educational level | −0.100 | 0.471 | 0.652 | 0.368 |

| Economic dependence | 0.058 | 0.013 | 0.514 | −0.748 |

| Sexual stereotypes | 0.064 | −0.238 | −0.144 | −0.597 |

| Factor | Degree | Closeness |

|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood networks | 1.00 | 0.89 |

| Socio-economic level | 0.75 | 0.77 |

| Family network | 0.75 | 0.77 |

| Sexual stereotypes | 0.75 | 0.77 |

| Similar family networks | 0.50 | 0.69 |

| Religious organization networks | 0.50 | 0.65 |

| Education networks | 0.25 | 0.59 |

| Friend network | 0.25 | 0.59 |

| Economic dependency | 0.25 | 0.59 |

| Partner educational level | 0.25 | 0.53 |

| Other networks | 0.00 | 0.34 |

| Partner sexual violence | 0.55 | 0.59 |

| Sexual violence in educational sphere | 0.55 | 0.59 |

| Sexual violence in work place | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| Sexual violence in public places | 0.36 | 0.52 |

| Factor | Degree | Closeness |

|---|---|---|

| Other networks | 1.00 | 0.89 |

| Educational level | 0.75 | 0.83 |

| Friend networks | 0.75 | 0.83 |

| Economic dependency | 0.75 | 0.83 |

| Educational level of partner | 0.75 | 0.69 |

| Similar family networks | 0.50 | 0.65 |

| Religious organizations network | 0.50 | 0.65 |

| Socio-economic level | 0.25 | 0.62 |

| Family network | 0.25 | 0.62 |

| Sexual stereotypes | 0.25 | 0.62 |

| Neighborhood network | 0.00 | 0.34 |

| Sexual violence in public spaces | 0.64 | 0.63 |

| Sexual violence in work spaces | 0.55 | 0.59 |

| Sexual violence in partnerships | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| Sexual violence in educational spaces | 0.45 | 0.55 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ilabaca Baeza, P.; Gaete Fiscella, J.M.; Hatibovic Díaz, F.; Roman Alonso, H. Social, Economic and Human Capital: Risk or Protective Factors in Sexual Violence? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020777

Ilabaca Baeza P, Gaete Fiscella JM, Hatibovic Díaz F, Roman Alonso H. Social, Economic and Human Capital: Risk or Protective Factors in Sexual Violence? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2):777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020777

Chicago/Turabian StyleIlabaca Baeza, Paola, José Manuel Gaete Fiscella, Fuad Hatibovic Díaz, and Helena Roman Alonso. 2022. "Social, Economic and Human Capital: Risk or Protective Factors in Sexual Violence?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 2: 777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020777

APA StyleIlabaca Baeza, P., Gaete Fiscella, J. M., Hatibovic Díaz, F., & Roman Alonso, H. (2022). Social, Economic and Human Capital: Risk or Protective Factors in Sexual Violence? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020777