Costs of an Alcohol Measurement Intervention in Three Latin American Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

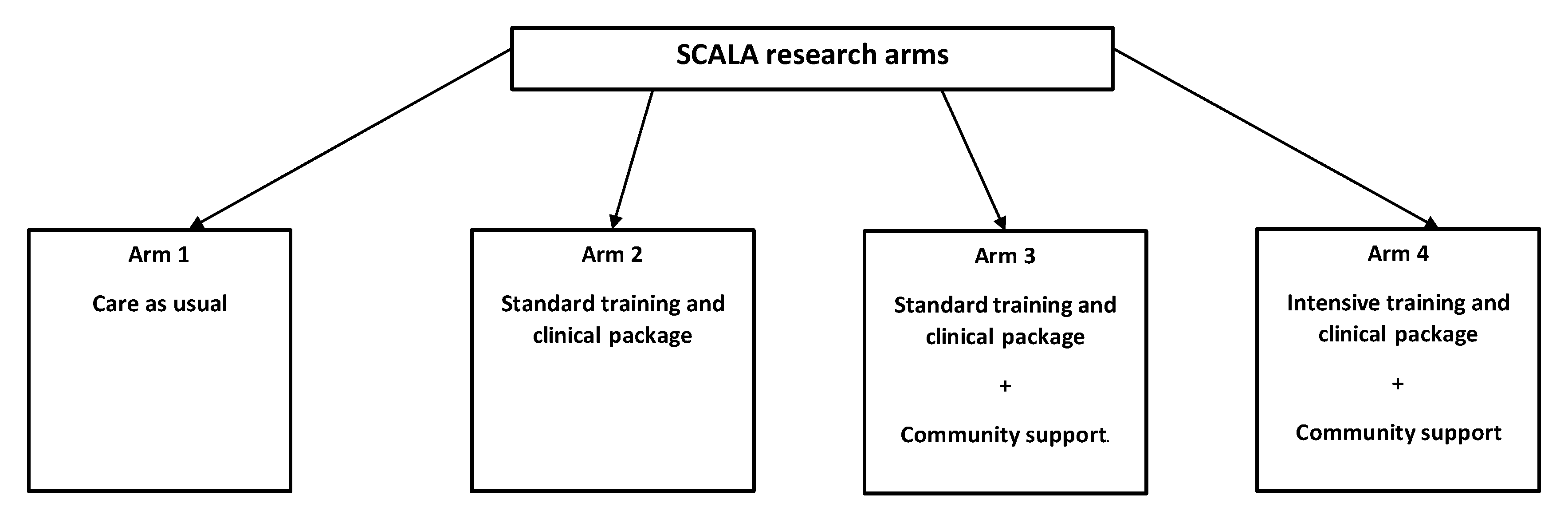

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Implementation Strategies

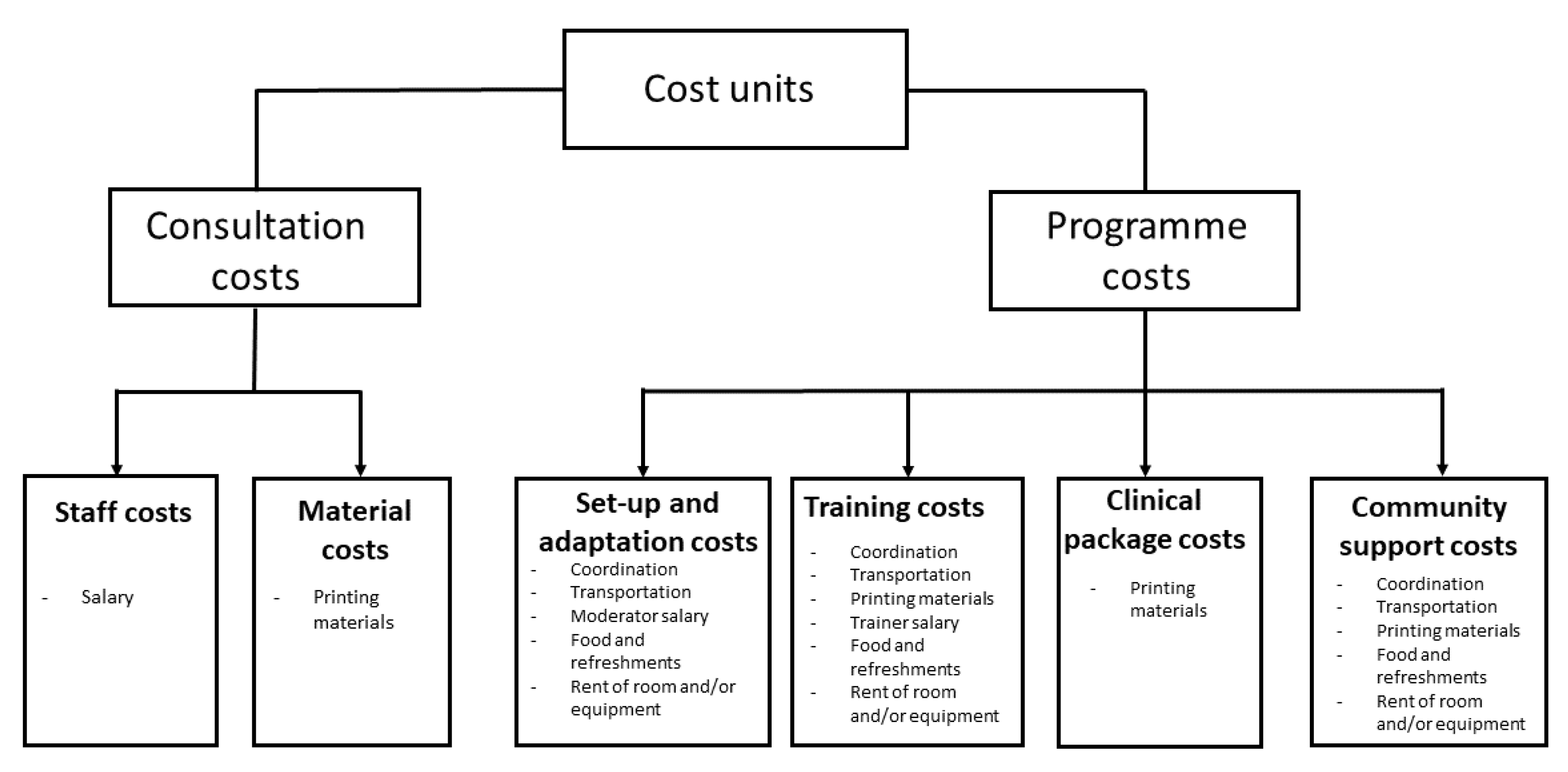

2.3. Costs Identification, Measurement, and Valuation

2.4. Consultation Costs

2.5. Programme Costs

2.6. Costs per Additional Alcohol Measurement Session

2.7. Costs per 10,000 Alcohol Measurement Sessions in SCALA

2.8. Statistical Testing

3. Results

3.1. Consultation Costs

3.2. Programme Costs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Colombia | Mexico | Peru | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health care systems | In Colombia, the health care system is regulated by the General System of Social Security in Health, which entails an universal health insurance programme managed by insurance companies. By 2017, 95% of the population were covered by public health insurance. Approximately 10% of the population (mainly in the higher SES segment) also own a private insurance scheme. | In Mexico, the health care system is segmented into several partially overlapping groups: (1) social security, covering workers and their families (about 63%), (2) “Seguro Popular”—a public health insurance conceived to provide health care for everyone (poor persons are exempted from paying insurance fees, about 46%), (3) private insurance (about 10%). | In Peru, the health care system is organised into five main programmes: (1) the “Seguro Integral de Salud/SIS“ programme, regulated by the Ministry of Health (for about 47% of the population); (2) the “EsSalud“ programme—a standard contributory health insurance scheme regulated by the Ministry of Labour and Employment Promotion, providing mandatory coverage for formal workers (25% of the population); (3) a programme regulated by the Armed Forces; (4) a programme regulated by the National Police; and (5) the private sector. The latter three sectors are estimated to cover health care services of about 5% of the population |

| Municipalities | With community support: Soacha (~700,000 inhabitants and an area of 184 km2, located in the metropolitan area of Bogota, in the department of Cundinamarca) Without community support: Funza (population ~75,000) and Madrid (population ~80,000) are located at 25 km distance from Bogota, in the department of Cundinamarca. | With community support: three municipalities in Mexico City: Tlaplan (~650,000 inhabitants); Benito Juares (~400,000 inhabitants); and Alvaro Obregon (~700,000 inhabitants) Without community support: two municipalities in Mexico City: Miguel Hidalgo (~400,000 inhabitants) and Xochimilco (~400,000 inhabitants) | With community support: Callao (~450,000 inhabitants, xx km), located in the proximity of Lima and of the Pacific Ocean, in the province Callao. Without community support: two districts in the Lima region: Chorrilos (~300,000 inhabitants, xx km) and Santiago de Surco (~300,000 inhabitants, xx km). |

| Infrastructure: congested traffic; private transportation services (e.g., taxi, hired minibuses) had to be used for project activities, rather than public transportation. Internet penetrance: medium, ~60% of the population has access to internet. | Infrastructure: congested traffic; private transportation services (e.g., taxi, hired minibuses) had to be used for project activities, rather than public transportation. Internet penetrance: medium, ~70% of the population has access to internet. | Infrastructure: congested traffic and safety risks in certain regions; private transportation services (e.g., taxi, hired minibuses) had to be used for project activities, rather than public transportation. Internet penetrance: medium, ~60% of the population has access to internet. |

| SCALA Study Arms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Arm 1 Care as Usual | Arm 2 Standard Training and Clinical Package | Arm 3 Community Support | Arm 4 Intensive Training and Clinical Package |

| Participants received: - A booklet describing a pathway for delivering alcohol measurement and subsequent interventions; - paper tally sheets with the AUDIT-C questionnaire (3 items) which could be used by providers to deliver the intervention; - no other support materials and activities were offered. | Participants received: - A booklet describing a pathway for delivering alcohol measurement and subsequent interventions; - paper tally sheets with the AUDIT-C questionnaire (3 items) which could be used by providers to deliver the intervention; - training (one session) before the start of the implementation, in which they were trained to deliver alcohol measurement and subsequent interventions using the same pathway as in arm 1; - patient leaflets (2 double-sided pages) to be offered to patients receiving brief advice. | Participants received: - A booklet describing a pathway for delivering alcohol measurement and subsequent interventions; paper tally sheets with the AUDIT-C questionnaire (3 items) which could be used by providers to deliver the intervention; - training (one session) before the start of the implementation, in which they were trained to deliver alcohol measurement and subsequent interventions using the same pathway as in arm 1; - patient leaflets (2 double-sided pages) to be offered to patients receiving brief advice; community support was offered to participating PHCC, in the form of supportive actions (e.g., regular feedback offered to providers) and CAB meetings. | Participants received: - A booklet describing a pathway for delivering alcohol measurement and subsequent interventions; paper tally sheets with the AUDIT questionnaire (10 items) which could be used by providers to deliver the intervention; - one training (two sessions in Mexico and Peru, one session in Colombia, which was longer that in the other arms) before the start of the implementation, in which they were trained to deliver alcohol measurement and subsequent interventions using a longer pathway than in arm 1; - patient leaflets (2 double-sided pages) to be offered to patients receiving brief advice; community support was offered to participating PHCC, in the form of supportive actions (e.g., regular feedback offered to providers) and CAB meetings. |

| Community Support Activity | Colombia | Mexico | Peru |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAB meetings | Two CAB meetings setting up the Municipal Actions Plan for the community actions intervention. | Two CAB meetings setting up the Municipal Actions Plan for the community actions intervention. | One CAB meeting setting up the Municipal Actions Plan for the community actions intervention. |

| Adoption mechanisms | 1. The benefits of the SCALA project have been emphasised in face-to-face meetings with centre managers and providers. 2. In implementation month 3, in a face to face meetings with providers, the number of screened patients was communicated. 3. A local university became engaged in the project. 4. In implementation month 3, in face to face meetings with providers, the highest alcohol measurement rates per centre were highlighted. 5. Organisational issues are monitored through discussions with centres; no substantial issues have been identified. | 1. During the training sessions, the benefits of implementing the alcohol measurement and brief advice in the centre for patients, providers, and the community have been highlighted. 2. In the training sessions, the large number of patients that can benefit if alcohol measurement and brief advice are implemented in the centre was reaffirmed. 3. A poster presentation was held at an Annual Research Meeting of the National Institute of Psychiatry; a presentation about the role of alcohol measurement was held on the National Day against Harmful use of Alcoholic Beverages 2019. 4. Informing centres about the percentage of alcohol measurement sessions carried out by each centre is done on a monthly basis. 5. Organisational issues are monitored through discussions with centres; no substantial issues have been identified. | 1. Collaboration with the Mental Health Program of the Ministry of Health, in order to promote the adoption of the program in the implementation municipality. 2. The large number of patients who benefit from the project was communicated to providers, focusing on three subgroups with higher alcohol risk in the intervention municipality: (a) persons in treatment of tuberculosis, (b) persons at risk of sexual transmitted diseases, and (c) persons in violent families. 3. In order to engage the municipality, 35 community promoters were trained in methods for working in alcohol prevention. 4. Lists were created for each centre using WhatsApp to promote the identification of champions. 5. Organisational issues are monitored through discussions with centres; one issue identified is that providers seem very busy. |

| Support systems | 1. Training packages were slightly shortened, in order to fit into the centres’ schedules and rules of attendance of providers. 2. One formal meeting was organised in the first two months of implementation to identify difficulties regarding the brief advice and the care pathway. 3. Meetings for feedback with providers held every two months, in which the alcohol measurement rates are communicated. | 1. Materials and activities of the training sessions were adjusted to the needs of each centre. 2. Reporting the number of alcohol measurement sessions to centres each month; informing centres every three months on the progress of the global project. | 1. Additional materials were added for new providers who did not have previous information about the program. 2. Reporting the number of alcohol measurement sessions each month to centres. 3. Exploring the option of involving Community Mental Health Services, who could train other centres in the future. |

| Profession | Colombia | Mexico | Peru |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP | 20.43 | 16.92 | 21.53 |

| Nurse | 8.18 | 10.07 | 9.83 |

| Social worker | 11.00 | 9.49 | 11.66 |

| Psychologist | 14.95 | 11.41 | 12.02 |

| Other | 11.87 | 6.41 | 14.13 |

| Colombia | Mexico | Peru | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard training and clinical package | 9.34 years Activities: - Start-up for five PHCCs and adaptation of clinical package materials. - One training in the first implementation year for 13 trained providers. - Eight boosters (one per following implementation year) for 13 trained providers. | 7.06 years Activities: - Start-up for five PHCCs and adaptation of clinical package materials. - Three trainings in the first implementation year for 44 trained providers. - Eighteen boosters (one per following implementation year) for 44 trained providers. | 4.92 years Activities: - Start-up for five PHCCs and adaptation of clinical package materials. - Four trainings in the first implementation year for 61 trained providers. - Twelve boosters (one per following implementation year) for 61 trained providers. |

| Community support (in SCALA combined with standard training and clinical package) | 2.27 years Activities: - Start-up for five PHCCs and adaptation of clinical package materials. - Two trainings in the first implementation year for 21 trained providers. - Two boosters (one per following implementation year) for 21 trained providers. - Three CAB meetings (two in the first year and one per following implementation year). - Set-up and implementation of supportive actions for 5 PHCCs. | 4.51 years Activities: - Start-up for five PHCCs and adaptation of clinical package materials. - Three trainings in the first implementation year for 45 trained providers. - Nine boosters (one per following implementation year) for 45 trained providers. - Five CAB meetings (two in the first year and one per following implementation year). - Set-up and implementation of supportive actions for 5 PHCCs. | 7.36 years Activities: - Start-up for five PHCCs and adaptation of clinical package materials. - Two trainings in the first implementation year for 34 trained providers. - Twelve boosters (one per following implementation year) for 34 trained providers. - Seven CAB meetings (one per implementation year). - Set-up and implementation of supportive actions for 5 PHCCs. |

| Intensive training and clinical package (in SCALA combined with community support) | 3.40 years Activities: - Start-up for five PHCCs and adaptation of clinical package materials. - One intensive training (one session) in the first implementation year for 17 trained providers. - Two boosters (one per following implementation year) for 15 trained providers. - Fours CAB meetings (two in the first year and one per following implementation year). -Set-up and implementation of supportive actions for 5 PHCCs. | 3.17 years Activities: - Start-up for four PHCCs and adaptation of clinical package materials. - Three intensive trainings (two sessions each) in the first implementation year for 50 trained providers. - Six boosters (one per following implementation year) for 38 trained providers. - Fours CAB meetings (two in the first year and one per following implementation year). - Set-up and implementation of supportive actions for 5 PHCCs. | 16.14 years Activities: - Start-up for five PHCCs and adaptation of clinical package materials. - Three intensive trainings (two sessions each) in the first implementation year for 41 trained providers. - Forty-five boosters (one per following implementation year) for 41 trained providers. - Fours CAB meetings (two in the first year and one per following implementation year). - Set-up (40 h) and implementation of supportive actions for 5 PHCCs (15 h monthly). |

| Unit | Unit Operationalisation | Quantity | Unit Cost (Int$) | Costs (Int$) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col | Mex | Per | Col | Mex | Per | Col | Mex | Per | ||

| Set-up and Adaptation Costs | ||||||||||

| Coordination of PHCC participation | Hours spent to coordinate participation of one PHCC. | 10 h | 10 h | 10 h | 14.95 per hour | 11.41 per hour | 12.02 per hour | 149.50 | 114.08 | 120.21 |

| Coordination user panel | Hours spent to coordinate and organise one user panel. | 20 h | 20 h | 20 h | 14.95 per hour | 11.41 per hour | 12.02 per hour | 299.00 | 228.17 | 40.41 |

| Food and refreshments | Food and refreshments in one user panel with 10 participants, including moderator and organiser. | 12 portions | 12 portions | 12 portions | 2.59 | 4.51 | 6.89 | 31.13 | 54.14 | 82.66 |

| Materials | Number of materials used during one user panel with 10 participants. | 10 sets | 10 sets | 10 sets | 1.48 per set | 3.65 per set | 3.10 per set | 14.83 | 36.52 | 31.00 |

| Remuneration moderator user panel | Number of hours spent by the moderator to prepare and deliver one user panel with 10 participants. | 4 h | 4 h | 4 h | 14.95 per hour | 11.41 per hour | 12.02 per hour | 59.80 | 45.63 | 48.08 |

| Transportation | Transportation used for one user panel with 10 participants, including moderator and organisers. | One transporation service | One transporation service | One transporation service | 37.06 | 107.42 | 71.76 | 37.06 | 107.42 | 71.76 |

| Adaptation of materials based on feedback | Hours spent to implement adaptation and tailoring of the clinical package materials. | 30 h | 30 h | 30 h | 14.95 per hour | 11.41 per hour | 12.02 per hour | 448.50 | 342.25 | 360.62 |

| Total set-up costs | Costs for coordinating the participation of 15 PHCCs in arms 2, 3, and 4. | 2242.50 | 1711.25 | 1803.10 | ||||||

| Total costs adaptation materials | Costs for two user panels and further adaptation of the clinical package materials. | 1332.15 | 1286.02 | 1308.45 | ||||||

| Standard Training and Clinical Package | ||||||||||

| Training coordination | Number of hours spent to coordinate one training session with 15 participants. | 20 h | 20 h | 20 h | 14.95 per hour | 11.41 per hour | 12.02 per hour | 299.00 | 228.17 | 240.41 |

| Participants materials | Number of materials used during one training session with 15 participants. | 15 sets | 15 sets | 15 sets | 2.59 per set | 5.37 per set | 5.74 per set | 38.92 | 80.57 | 86.11 |

| Remuneration trainer | Number of hours spent by the trainer to prepare and deliver one training session with 15 participants. | 3 h | 4 h | 4 h | 18.82 per hour | 20.41 per hour | 16.19 per hour | 56.46 | 81.64 | 64.75 |

| Food and refreshments (one training) | Food and refreshments in one training session with 15 participants, including trainer and organiser. | 17 portions | 17 portions | 17 portions | 2.59 per portion | 4.51 per portion | 6.89 per portion | 44.11 | 76.70 | 117.11 |

| Transportation (one training) | Transportation used for one training session with 15 participants, including trainer and organisers. | One transporation service | One transporation service | One transporation service | 37.06 | 75.20 | 71.76 | 37.06 | 75.20 | 71.76 |

| Total costs for one standard training | 475.55 | 542.27 | 580.14 | |||||||

| Total costs for one trained provider (standard training) | 31.70 | 36.15 | 38.68 | |||||||

| Clinical package materials for alcohol measurement | Number of double-sided pages used in the standard clinical package for each new patient whose alcohol consumption is measured. | 2 double- sided pages | 2 double- sided pages | 2 double- sided pages | 0.15 per double- sided page | 0.27 per double- sided page | 0.26 per double- sided page | 0.30 | 0.54 | 0.52 |

| Intensive Training and Clinical Package | ||||||||||

| Total costs for one intensive training | Total costs for one intensive training consisting of one session in Colombia and two sessions in Mexico and Peru. | 547.09 | 1050.22 | 881.99 | ||||||

| Total costs for one trained provider (intensive training) | 36.47 | 63.01 | 64.14 | |||||||

| Additional costs intensive training per provider (compared to standard training) | Additional costs, per provider, spent to provide intensive training (over and above standard training). | 6.50 | 30.01 | 21.11 | ||||||

| Additional time full AUDIT | Additional number of minutes spent to measure the alcohol consumption of a new patient, with the full AUDIT (over and above AUDIT-C). | 3.75 min | 2 min | 5 min | 15.69 per hour | 13.77 per hour | 12.76 per hour | 0.98 | 0.46 | 1.06 |

| Additional alcohol measurement material | Number of additional double-sided pages used for the full AUDIT assessment, for each new patient whose alcohol consumption is measured (as compared to care as usual). | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.07 per page | 0.1 per page | 0.1 per page | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Community Support | ||||||||||

| CAB coordination and moderation | Number of hours spent to prepare and coordinate one CAB meeting. | 35 h | 35 h | 35 h | 14.95 per hour | 11.41 per hour | 12.02 per hour | 523.25 | 399.29 | 420.72 |

| Venue rent | Venue rent for one CAB meeting. | 1 conference hall | 1 conference hall | none | 111.19 | 268.56 | -- | 111.19 | 268.56 | 0.00 |

| Food and refreshments | Food and refreshments used in one CAB meeting. | 12 portions | 12 portions | 12 portions | 2.59 per portion | 4.51 per portion | 9.57 per portion | 31.13 | 54.14 | 82.66 |

| Materials | Amount of materials used in one CAB meeting. | 10 sets | 10 sets | 10 sets | 1.48 per set | 3.65 per set | 3.05 per set | 14.80 | 32.52 | 30.54 |

| Transportation | Transportation used for one CAB meeting. | One transporation service | One transporation service | One transporation service | 37.06 | 75.20 | 71.76 | |||

| Total cost one CAB meeting | Total costs for one CAB meeting. | 717.44 | 833.71 | 605.68 | ||||||

| Set-up supportive actions | Amount of hours spent to set-up and prepare supportive actions for 1 municipality, including 10 PHCCs. | 40 h | 40 h | 40 h | 14.95 per hour | 11.41 per hour | 12.02 per hour | 598.00 | 456.33 | 480.83 |

| Coordination and implementation supportive actions | Amount of hours spent to implement supportive actions for one municipality, including 10 PHCCs, during 1 month. | 20 h | 10 h | 10 h | 14.95 per hour | 11.41 per hour | 12.02 per hour | 299.00 | 171.12 | 120.21 |

| Total cost of supportive actions (1 municipality, 5 months) | Total costs of implementing supportive actions in 1 municipality, including 10 PHCCs. | 1495.00 | 855.62 | 601.03 | ||||||

| Total costs of community support | Total costs of 5 months of community support in 1 municipality, consisting of two CAB meetings in Colombia and Mexico, one CAB meeting in Peru, and five months of supportive actions. | 2929.88 | 2523.04 | 1206.72 | ||||||

References

- Chrystoja, B.R.; Rehm, J.; Manthey, J.; Probst, C.; Wettlaufer, A.; Shield, K.D. A Systematic Comparison of the Global Comparative Risk Assessments for Alcohol. Addiction 2021, 116, 2026–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shield, K.; Manthey, J.; Rylett, M.; Probst, C.; Wettlaufer, A.; Parry, C.D.H.; Rehm, J. National, Regional, and Global Burdens of Disease from 2000 to 2016 Attributable to Alcohol Use: A Comparative Risk Assessment Study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e51–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol Use and Burden for 195 Countries and Territories, 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, J.; Hassan, S.A.; Carr, S.; Kilian, C.; Kuitunen-Paul, S.; Rehm, J. What Are the Economic Costs to Society Attributable to Alcohol Use? A Systematic Review and Modelling Study. Pharmacoeconomics 2021, 39, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1659–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, J.; Shield, K.D.; Rylett, M.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Probst, C.; Rehm, J. Global Alcohol Exposure between 1990 and 2017 and Forecasts until 2030: A Modelling Study. Lancet 2019, 393, 2493–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Making the European Region Safer: Developments in Alcohol Control Policies, 2010–2019; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, K.; Kivlahan, D.R.; McDonell, M.B.; Fihn, S.D.; Bradley, K.A. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): An Effective Brief Screening Test for Problem Drinking. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998, 158, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, K.; Batra, A.; Fauth-Bühler, M.; Hoch, E. German Guidelines on Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorders. Eur. Addict. Res. 2017, 23, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- sNICE. NICE Pathways. Screening and Brief Interventions for Harmful Drinking and Alcohol Dependence. Available online: https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/alcohol-use-disorders#path=view%3A/pathways/alcohol-use-disorders/screening-and-brief-interventions-for-harmful-drinking-and-alcohol-dependence.xml&content=view-index (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Babor, T.F.; McRee, B.G.; Kassebaum, P.A.; Grimaldi, P.L.; Ahmed, K.; Bray, J. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): Toward a Public Health Approach to the Management of Substance Abuse. Subst. Abus. 2007, 28, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.; Chisholm, D.; Fuhr, D.C. Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Policies and Programmes to Reduce the Harm Caused by Alcohol. Lancet 2009, 373, 2234–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaner, E.F.S.; Beyer, F.R.; Muirhead, C.; Campbell, F.; Pienaar, E.D.; Bertholet, N.; Daeppen, J.B.; Saunders, J.B.; Burnand, B. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2, CD004148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, A.; Wallace, P.; Kaner, E. From Efficacy to Effectiveness and beyond: What next for Brief Interventions in Primary Care? Front. Psychiatry 2014, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Johnson, M.; Jackson, R.; Guillaume, L.; Meier, P.; Goyder, E. Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing Screening and Brief Intervention for Alcohol Misuse: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Evidence. J. Public Health 2011, 33, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.; Cowell, A.J.; Landwehr, J.; Dowd, W.; Bray, J.W. Cost of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment in Health Care Settings. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2016, 60, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, J.W.; Zarkin, G.A.; Hinde, J.M.; Mills, M.J. Costs of Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention in Medical Settings: A Review of the Literature. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2012, 73, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkin, G.A.; Bray, J.W.; Davis, K.L.; Babor, T.F.; Higgins-Biddle, J.C. The Costs of Screening and Brief Intervention for Risky Alcohol Use. J. Stud. Alcohol 2003, 64, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neighbors, C.J.; Barnett, N.P.; Rohsenow, D.J.; Colby, S.M.; Monti, P.M. Cost-Effectiveness of a Motivational Intervention for Alcohol-Involved Youth in a Hospital Emergency Department. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2010, 71, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, B.; Baltussen, R.; Hutubessy, R. Programme Costs in the Economic Evaluation of Health Interventions. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2003, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jané-Llopis, E.; Anderson, P.; Piazza, M.; O’Donnell, A.; Gual, A.; Schulte, B.; Pérez Gómez, A.; de Vries, H.; Natera Rey, G.; Kokole, D.; et al. Implementing Primary Healthcare-Based Measurement, Advice and Treatment for Heavy Drinking and Comorbid Depression at the Municipal Level in Three Latin American Countries: Final Protocol for a Quasiexperimental Study (SCALA Study). BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.; Manthey, J.; Llopis, E.J.; Rey, G.N.; Bustamante, I.V.; Piazza, M.; Aguilar, P.S.M.; Mejía-Trujillo, J.; Pérez-Gómez, A.; Rowlands, G.; et al. Impact of training and municipal support on primary health care–based measurement of alcohol consumption in three Latin American countries: 5-month outcome results of the quasi-experimental randomized SCALA trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 2663–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, A.; Schulte, B.; Manthey, J.; Schmidt, C.S.; Piazza, M.; Bustamante, I.; Natera, G.; Aguilar, N.B.; Hernández, G.Y.S.; Mejía-Trujillo, J.; et al. Primary care-based screening and management of depression amongst heavy drinking patients: Interim secondary outcomes of a three-country quasi-experimental study in Latin America. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovei, A.; Mercken, L.; Jané-Llopis, E.; Bustamante, I.; Evers, S.; Gual, A.; Medina, P.; Mejía-Trujillo, J.; Natera-Rey, G.; O’Donnell, A.; et al. Development of community strategies supporting brief alcohol advice in three Latin American countries: A protocol. Health Prom. Int. 2021, daab192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. PPP Conversion Factor, GDP (LCU per International $). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPP (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Wamsley, M.; Satterfield, J.M.; Curtis, A.; Lundgren, L.; Satre, D.D. Alcohol and Drug Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) training and implementation: Perspectives from 4 health professions. J. Addic. Med. 2018, 12, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manthey, J.; Carr, S.; Anderson, P.; Bautista, N.; Braddick, F.; O’Donnell, A.; Jané-Llopis, E.; López-Pelayo, H.; Medina, P.; Mejía-Trujillo, J.; et al. Reduced alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analyses of 17,000 patients seeking primary health care in Colombia and Mexico. J. Glob. Health, 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S.; Rehm, J.; Manthey, J. Guidelines and Reality in Studies on the Economic Costs of Alcohol Use: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Alcohol Drug Res. 2021, 9, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unit | Operationalisation | Quantity | Unit Cost | Costs (Int$) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col | Mex | Per | Col | Mex | Per | Col | Mex | Per | ||

| Alcohol measurement session | Minutes spent by provider to measure alcohol use in a new patient, using the AUDIT-C questionnaire. | 4.3 (CI:3.46; 5.13) | 2.43 (CI:0.75; 4.1) | 4.73 (CI:4.54; 4.93) | Int$ 15.69 per hour | Int$ 13.77 per hour | Int$ 12.76 per hour | 1.12 (CI:0.90; 1.34) | 0.57 (CI:0.17; 0.94) | 1.01 (CI:0.97; 1.05) |

| Brief advice session | Minutes spent by provider to deliver a brief advice session to a patient. | 5.26 (CI:4.27; 6.25) | 4.14 (CI:1.35; 6.94) | 4.85 (CI:4.59; 5.12) | 1.38 (CI:1.12; 1.63) | 0.95 (CI:0.31; 1.59) | 1.03 (CI:0.98; 1.09) | |||

| Referral to treatment session | Minutes spent by provider to deliver a referral to treatment session to a patient. | 2.50 (CI:1.94; 3.06) | 2.43 (CI:0.63; 4.22) | 1.60 (CI:1.46; 1.74) | 0.65 (CI:0.54; 0.80) | 0.56 (CI:0.14; 0.97) | 0.34 (CI:0.31; 0.37) | |||

| Alcohol measurement material | Number of double-sided pages used for the AUDIT-C tally sheet, for each new patient whose alcohol consumption is measured. | 1 | 1 | 1 | Int$ 0.07 per page | Int$ 0.1 per page | Int$ 0.1 per page | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Consultation cost and alcohol measurement session | Costs incurred for every new patient whose alcohol consumption was measured, who did not receive subsequent interventions (staff costs + materials). | 1.19 (CI:0.97; 2.54) | 0.67 (CI:0.27; 1.04) | 1.11 (CI:1.07; 1.15) | ||||||

| Consultation cost, alcohol measurement, and brief advice session | Costs incurred for every new patient whose alcohol consumption was measured and received brief advice (staff costs + materials). | 2.57 (CI:2.09; 4.17) | 1.62 (CI:0.58; 2.63) | 2.14 (CI:2.05; 2.24) | ||||||

| Consultation cost, alcohol measurement, and referral to treatment session | Costs incurred for every new patient whose alcohol consumption was measured and received referral to treatment (staff costs + materials). | 1.84 (CI:1.51; 3.34) | 1.23 (CI:0.41; 2.01) | 1.45 (CI:1.38; 1.52) | ||||||

| Nr. of Alcohol Measurement Sessions Delivered in 5 Months of SCALA Implementation, and nr. of Participating Providers and PHCCs, per Study Arm. | Period within Which 10,000 Alcohol Measurement Sessions Would Be Delivered in One SCALA Study Arm | Programme and Consultation Costs for 10,000 Alcohol Measurement Sessions (Int$) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col | Mex | Per | Col | Mex | Per | Col | Mex | Per | |

| Standard training and clinical package | 446 (30 providers in five PHCCs) | 590 (54 providers in five PHCCs) | 846 (70 providers in five PHCCs) | 9.34 years | 7.06 years | 4.92 years | 20,082.85 | 22,177.18 | 25,474.28 |

| Community support (in SCALA combined with standard training and clinical package) | 1830 (26 providers in five PHCCs) | 922 (59 providers in five PHCCs) | 566 (40 providers in five PHCCs) | 2.27 years | 4.51 years | 7.36 years | 24,654.26 | 27,474.40 | 34,103.66 |

| Intensive training and clinical package (in SCALA combined with community support) | 1222 (17 providers in five PHCCs) | 1313 (47 providers in four PHCCs) | 258 (50 providers in five PHCCs) | 3.40 years | 3.17 years | 16.14 years | 37,506.26 | 30,360.53 | 74,414.28 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solovei, A.; Manthey, J.; Anderson, P.; Mercken, L.; Jané Llopis, E.; Natera Rey, G.; Pérez Gómez, A.; Mejía Trujillo, J.; Bustamante, I.; Piazza, M.; et al. Costs of an Alcohol Measurement Intervention in Three Latin American Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020700

Solovei A, Manthey J, Anderson P, Mercken L, Jané Llopis E, Natera Rey G, Pérez Gómez A, Mejía Trujillo J, Bustamante I, Piazza M, et al. Costs of an Alcohol Measurement Intervention in Three Latin American Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2):700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020700

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolovei, Adriana, Jakob Manthey, Peter Anderson, Liesbeth Mercken, Eva Jané Llopis, Guillermina Natera Rey, Augusto Pérez Gómez, Juliana Mejía Trujillo, Inés Bustamante, Marina Piazza, and et al. 2022. "Costs of an Alcohol Measurement Intervention in Three Latin American Countries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 2: 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020700

APA StyleSolovei, A., Manthey, J., Anderson, P., Mercken, L., Jané Llopis, E., Natera Rey, G., Pérez Gómez, A., Mejía Trujillo, J., Bustamante, I., Piazza, M., Pérez de León, A., Arroyo, M., de Vries, H., Rehm, J., & Evers, S. (2022). Costs of an Alcohol Measurement Intervention in Three Latin American Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020700