Key Components for the Delivery of Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Care Homes in Hong Kong: A Modified Delphi Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

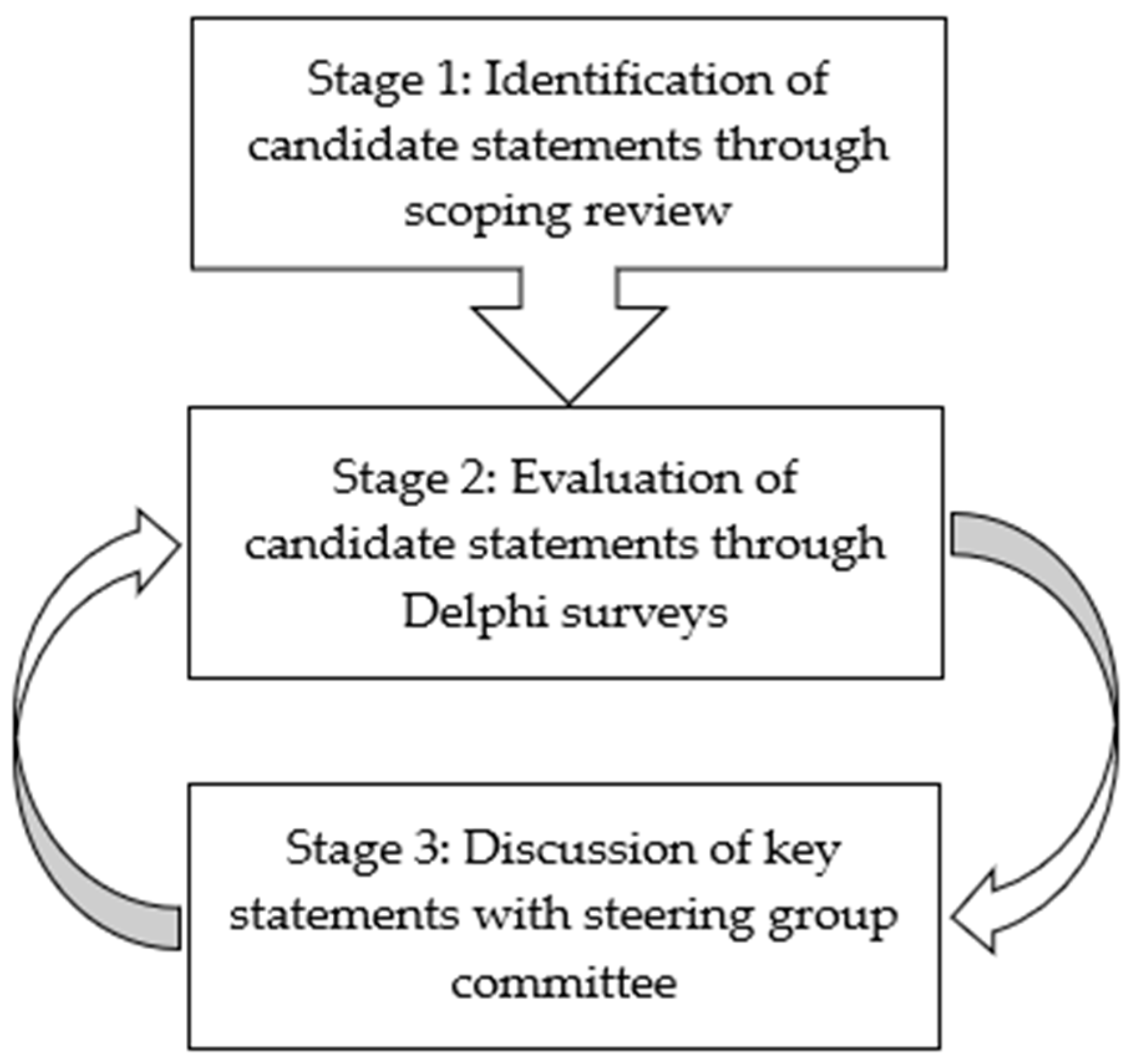

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stage 1: Identification of Candidate Statements

2.2. Stage 2: Evaluation of Candidate Statements through Delphi Surveys

2.3. Stage 3: Discussion of Key Statements

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Candidate Statements

3.2. Results of Delphi Surveys

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

4.2. Conceptual Framework

4.3. Tailored to the Socio-Cultural Context

4.4. Strengths

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oliver, D.P.; Washington, K.; Kruse, R.L.; Albright, D.L.; Lewis, A.; Demiris, G. Hospice family members’ perceptions of and experiences with end-of-life care in the nursing home. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Temkin-Greener, H.; Zheng, N.; Norton, S.A.; Quill, T.; Ladwig, S.; Veazie, P. Measuring end-of-life care processes in nursing homes. Gerontologist 2009, 49, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinley, J.; Hockley, J.; Stone, L.; Dewey, M.; Hansford, P.; Stewart, R.; McCrone, P.; Begum, A.; Sykes, N. The provision of care for residents dying in UK nursing care homes. Age Ageing 2014, 43, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, P.E.; Stefanacci, R.G.; Feuerman, M. Prevalence and description of palliative care in US nursing homes: A descriptive study. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2016, 33, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyniers, T.; Deliens, L.; Pasman, H.R.; Morin, L.; Addington-Hall, J.; Frova, L.; Cardenas-Turanzas, M.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.; Naylor, W.; Ruiz-Ramos, M.; et al. International variation in place of death of older people who died from dementia in 14 European and non-European countries. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivodic, L.; Smets, T.; Van den Noortgate, N.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; Engels, Y.; Szczerbińska, K.; Finne-Soveri, H.; Froggatt, K.; Gambassi, G.; Deliens, L.; et al. Quality of dying and quality of end-of-life care of nursing home residents in six countries: An epidemiological study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1584–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froggatt, K.A.; Payne, S.; Morbey, H.; Edwards, M.; Finne-Soveri, H.; Gambassi, G.; Pasman, H.R.; Szczerbińska, K.; Van den Block, L. Palliative care development in European care homes and nursing homes: Application of a typology of implementation. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 550.e7–550.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National End of Life Care Intelligence Network. The Role of Care Homes in End of Life Care; Public Health England, UK, 2017; Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/828120/Briefing_1_Care_home_provision_and_potential_end_of_life_care.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Irajpour, A.; Hashemi, M.; Taleghani, F. The quality of guidelines on the end-of-life care: A systematic quality appraisal using AGREE II instrument. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 1555–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government. Guidelines for a Palliative Approach in Residential Aged Care; The National Palliative Care Program, Australia, 2006. Available online: https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-06/RCD.9999.0049.0016.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority. Guidelines for Palliative and End of Life Care in Nursing Homes and Residential Care Homes; Guidelines and Audit Implementation Network; Belfast, Northern Ireland, 2013; Available online: https://www.rqia.org.uk/RQIA/files/6c/6cfdca9d-a1f1-432e-bca0-06e42cd181e9.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Temkin-Greener, H.; Ladwig, S.; Caprio, T.; Norton, S.; Quill, T.; Olsan, T.; Cai, X.; Mukamel, D.B. Developing palliative care practice guidelines and standards for nursing home-based palliative care teams: A Delphi study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 86.e1–86.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froggatt, K.A.; Collingridge Moore, D.; Van den Block, L.; Ling, J.; Payne, S.A.; PACE consortium collaborative authors on behalf of EAPC. Palliative care implementation in long-term care facilities: European Association for Palliative Care White Paper. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, E.; Kiang, N.; Chung, R.Y.-N.; Lau, J.; Chau, P.Y.-K.; Wong, S.Y.-S.; Woo, J.; Chan, E.Y.-Y.; Yeoh, E.-K. Quality of palliative and end-of-life care in Hong Kong: Perspectives of healthcare providers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, R.Y.-N.; Wong, E.L.-Y.; Kiang, N.; Chau, P.Y.-K.; Lau, J.Y.; Wong, S.Y.-S.; Yeoh, E.-K.; Woo, J.W. Knowledge, attitudes, and preferences of advance decisions, end-of-life care, and place of care and death in Hong Kong. A population-based telephone survey of 1067 adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 367.e19–367.e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.W.; Luk, J.K.H.; Hui, E.; Chiu, P.K.C.; Chan, C.S.Y.; Kwan, F.; Kwok, K.; Lee, D.; Woo, J. Advance Directive and End-of-Life Care Preferences Among Chinese Nursing Home Residents in Hong Kong. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2011, 12, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.Y.L.; Lee, D.T.F.; Woo, J. Diagnosing gaps in the development of palliative and end-of-life care: A qualitative exploratory study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.L.; Swagerty, D.; Barbagallo, M.; Vellas, B.; Cha, H.B.; Holmerova, I.; Dong, B.; Koopmans, R.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Robledo, L.M.G.; et al. IAGG/IAGG GARN International Survey of End-of-Life Care in Nursing Homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S.; McKenna, H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Jünger, S.; Payne, S.A.; Brine, J.; Radbruch, L.; Brearley, S.G. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulkedid, R.; Abdoul, H.; Loustau, M.; Sibony, O.; Alberti, C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, C. The Delphi technique: Myths and realities. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 41, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donabedian, A. The quality of care: How can it be assessed? J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1988, 260, 1743–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinley, J.; Froggatt, K.; Bennett, M.I. The effect of policy on end-of-life care practice within nursing care homes: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.; Agnelli, J.; McGreevy, J.; Diamond, M.; Roble, H.; McShane, E.; Strain, J. Palliative and end-of-life care for people living with dementia in care homes: Part 2. Nurs. Stand. 2016, 30, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, J.R.; Poetker, D.M.; Aksoy, U.; Allevi, F.; Biglioli, F.; Cha, B.Y.; Chiapasco, M.; Lechien, J.R.; Safadi, A.; Dds, R.S.; et al. Diagnosing odontogenic sinusitis: An international multidisciplinary consensus statement. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021, 11, 1235–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstey, S.; Powell, T.; Coles, B.; Hale, R.; Gould, D. Education and training to enhance end-of-life care for nursing home staff: A systematic literature review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2016, 6, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.Y.L.; Kwok, A.O.L.; Yuen, K.K.; Au, D.K.S.; Yuen, J.K.Y. Association between training experience and readiness for advance care planning among healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ 2020, 20, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.W.H.; Ng, N.H.Y.; Chan, H.Y.L.; Wong, M.M.H.; Chow, K.M. A systematic review of the effects of advance care planning facilitators training programs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019, 19, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumsion, T. The Delphi technique: An adaptive research tool. Brit. J. Occup. Ther. 1998, 61, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain/Statements | Percentage of Agreement 1 | Median 2 |

|---|---|---|

| I. Policy | ||

| 1. Formulating a framework to promote end-of-life care practices in care home setting. | 83.3 | 4.0 |

| 2. Developing an administrative policy specific to end-of-life care. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 3. Developing clinical policies and protocols to encourage documentation of the care practices. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 4. Having a professional body to provide guidance on the care implementation. | 94.4 | 4.0 |

| 5. Having an external reviewer to visit and monitor how the care practices are provided in place. | 72.2 | 4.0 |

| II. Philosophy of care | ||

| 6. Adopting a shared care approach. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 7. Treat residents with respect, kindness and dignity. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 8. Promote person-centred, personalized, and holistic care. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 9. Being responsive to the needs of patients and family members in a timely manner. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 10. Preserving residents’ dignity, privacy, and autonomy. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| III. Organization support | ||

| 11. Institutional leadership to support end-of-life care practices. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 12. Building a quality assurance mechanism to monitor the quality of end-of-life care. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 13. Reflecting on the quality of care in a continuous fashion. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 14. Designing remembrance activities to encourage open atmosphere to talk about death. | 83.3 | 4.0 |

| 15. Acknowledging the time devoted to support end-of-life care practices. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| IV. Staffing and training | ||

| 16. Ensuring staff adequacy and staff–resident ratio for supporting end-of-life care. | 66.7 | 4.0 |

| 17. Building a multidisciplinary team to address the complex care needs. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 18. Providing specific staff training tailored to the context and needs of care home setting. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 19. Including medico–ethical–legal issues in the training. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 20. Providing mentoring to ancillary staff members. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 21. Offering guidance at the bedside care. | 88.9 | 5.0 |

| 22. Provide continuous staff education on a specific topic or issue. | 88.9 | 5.0 |

| 23. Providing support to staff through counselling, debriefing, and bereavement care. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 24. Foster a learning culture for sharing knowledge and information about clients’ conditions or needs. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| V. Environment and facilities | ||

| 25. Providing a calm and private environment. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 26. Creating a welcoming atmosphere to encourage family visitation. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 27. Providing space and facilities for family members to stay overnight to accompany the resident in the last days of life. | 66.7 | 4.0 |

| VI. Identification of care needs | ||

| 28. Identifying the phase of illness of residents. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 29. Conducting a structured and systematic approach for assessing physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs of residents. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 30. Timely detection of changes in residents’ health status. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 31. Using valid and appropriate tools to assess the physical symptoms of the residents, especially for residents with cognitive impairment. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 32. Assessing non-verbal cues of pain and distress (agitation and restless). | 66.7 | 4.0 |

| 33. Formulate a supportive care plan for each resident to summarize the actual and anticipated needs. | 55.6 | 4.0 |

| VII. Physical care | ||

| 34. Ensuring adequate basic care to maintain cleanliness and comfort. | 100.0 | 5.0 |

| VIII. Pain and symptom management | ||

| 35. Adopting pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies for symptom alleviation or control. | 100.0 | 4.0 |

| 36. Regular medication review to manage symptoms. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 37. Arrange prescription of anticipatory medication for possible distress. | 72.2 | 4.0 |

| 38. Ongoing symptom management, in particular difficulties in breathing and nausea. | 88.9 | 5.0 |

| IX. Psychosocial care | ||

| 39. Providing counselling or reassurance to cope with stress and anxiety. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 40. Including trained volunteers in care delivery. | 27.8 | 3.0 |

| 41. Providing a supportive presence with the dying resident. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 42. Providing bereavement care to family members. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| X. Spiritual care | ||

| 43. Exploring the spiritual, religious, and existential concerns of residents and family members. | 50.0 | 3.0 |

| 44. Providing support to the search for meaning, forgiveness, and reconciliation. | 66.7 | 4.0 |

| 45. Providing or facilitating individual devotional activities for dying residents. | 66.7 | 4.0 |

| XI. Coordination and collaboration | ||

| 46. Designating a staff member as a named lead for the resident. | 66.7 | 4.0 |

| 47. Holding regular meetings to discuss the residents’ care. | 66.7 | 4.0 |

| 48. Maintaining a good rapport with the hospital, discharge planning coordinator, and community care team. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 49. Maintaining communication about care, in particular out-of-service hours. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 50. Collaborating with specialist palliative care team in complex cases. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 51. Collaborating with general practitioners. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| XII. Communication | ||

| 52. Preparing resident and family for end-of-life care (emotionally/intellectually). | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 53. Providing information to resident and family about end-of-life care and the dying process. | 77.8 | 5.0 |

| 54. Initiating advance care planning with residents and family members to clarify preferred place of care and treatment preferences. | 77.8 | 4.0 |

| 55. Planning for funeral arrangement. | 55.6 | 4.0 |

| 56. Documenting the conversations within easy access. | 55.6 | 4.0 |

| 57. Review the care plan regularly or when necessary. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| XIII. Family support | ||

| 58. Promoting family involvement in care and decision-making. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 59. Meeting with the family members on regular basis to explore their views towards the residents’ care. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 60. Allowing the family and individuals of residents’ choice to be present in the dying phase. | 88.9 | 4.0 |

| 61. Providing support to aftermath care and bereavement care to family members. | 88.6 | 4.0 |

| Domains/Statements | Type 1 |

|---|---|

| A. Policy and infrastructure | |

| 1. Having policies and guidelines regarding palliative and end-of-life care. | S |

| 2. Providing facilities to support the implementation of palliative and end-of-life care. | S |

| 3. Providing private space for the family members and friends of the dying resident. | S |

| B. Education | |

| 4. Providing training and supervision in palliative and end-of-life care to meet the staff’s learning needs. | S |

| 5. Providing education for the residents and their family members to enhance their knowledge and understanding of palliative and end-of-life care. | S |

| C. Assessment | |

| 6. Regularly assessing the residents’ care needs and documenting the results. | P |

| 7. Using standardized assessment tools to periodically evaluate the pain experienced by the residents and the effects of pain management. | P |

| 8. Including nutritional screening in the initial assessment. | P |

| 9. Identifying the risks of poor nutrition, dehydration, or swallowing difficulties. | P |

| 10. Formulating and regularly reviewing nutrition and hydration care plans. | P |

| D. Symptom management | |

| 11. Managing physical symptoms and medication side effects in a systematic approach. | P |

| 12. Managing the prescription of controlled drugs according to the local laws. | P |

| 13. Providing adequate analgesics and/or sedatives for a dying resident to alleviate pain. | P |

| 14. Making referrals to specialist palliative care services when deemed necessary due to the residents’ care needs. | P |

| E. Communication | |

| 15. Regularly assessing residents, their family members, or representatives of the assessment results, based on their choices. | P |

| 16. Recording and reviewing periodically end-of-life care preferences of the residents and their family members. | P |

| 17. Including residents’ preferences and religious, spiritual, and cultural beliefs and involving their family members in advance care planning. | P |

| 18. Consulting family members if the residents can no longer make decisions due to declining health. | P |

| 19. Immediately notifying family members and other residents when a resident is detected with signs of impending death. | P |

| 20. Providing emotional support for other residents and staff following a resident’s death and prepare a remembrance event based on the residents’ preferences. | P |

| F. Care for dying residents | |

| 21. Providing care in a respectful manner with consideration of the cultural and religious practices of the dying resident. | P |

| 22. Handling the deceased resident’s body according to guidelines, local laws, and regulations. | P |

| 23. Making arrangements for the personal possessions of the deceased resident in a timely and respectful manner according to his/her preferences. | P |

| G. Family support | |

| 24. Allowing sufficient time for the family members and friends to accompany the dying resident. | P |

| 25. Providing family members with timely guidance or information regarding signs and symptoms of the dying resident. | P |

| 26. Providing bereavement counseling for the family members or representatives. | P |

| 27. Providing family members or representatives with information regarding registration of death and funeral arrangements. | P |

| 28. Assessing the family needs for bereavement support services and providing information as necessary. | P |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chan, H.Y.-L.; Chan, C.N.-C.; Man, C.-W.; Chiu, A.D.-W.; Liu, F.C.-F.; Leung, E.M.-F. Key Components for the Delivery of Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Care Homes in Hong Kong: A Modified Delphi Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020667

Chan HY-L, Chan CN-C, Man C-W, Chiu AD-W, Liu FC-F, Leung EM-F. Key Components for the Delivery of Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Care Homes in Hong Kong: A Modified Delphi Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2):667. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020667

Chicago/Turabian StyleChan, Helen Yue-Lai, Cecilia Nim-Chee Chan, Chui-Wah Man, Alice Dik-Wah Chiu, Faith Chun-Fong Liu, and Edward Man-Fuk Leung. 2022. "Key Components for the Delivery of Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Care Homes in Hong Kong: A Modified Delphi Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 2: 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020667

APA StyleChan, H. Y.-L., Chan, C. N.-C., Man, C.-W., Chiu, A. D.-W., Liu, F. C.-F., & Leung, E. M.-F. (2022). Key Components for the Delivery of Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Care Homes in Hong Kong: A Modified Delphi Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020667