Health Literacy and Change in Health-Related Quality of Life in Dialysed Patients

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

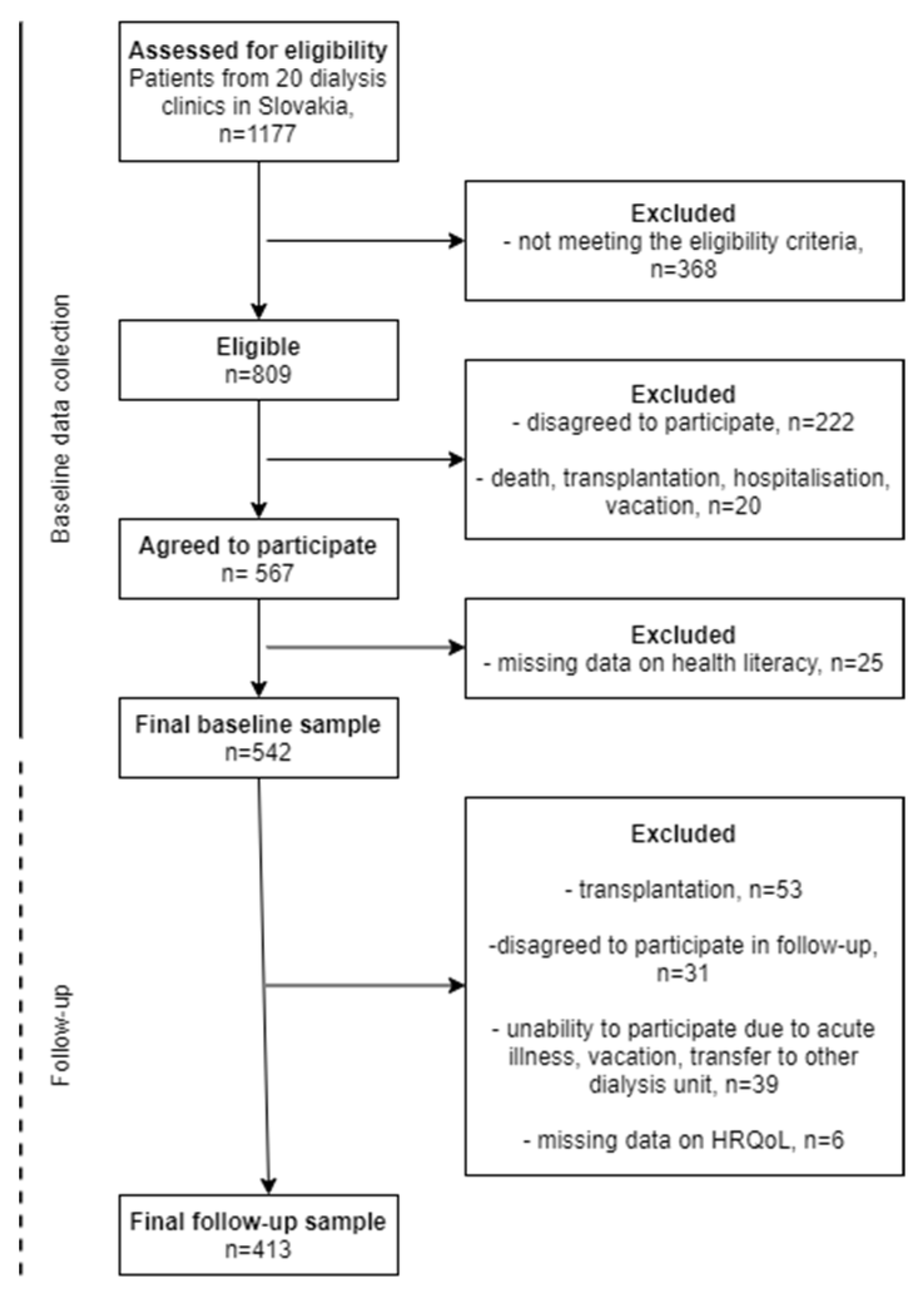

2.1. Sample and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Baseline and Follow-Up Characteristics

3.2. Association of Health Literacy with Baseline Health-Related Quality of Life

3.3. Health Literacy and Deterioration in Health-Related Quality of Life

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jha, V.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Iseki, K.; Li, Z.; Naicker, S.; Plattner, B.; Saran, R.; Wang, A.Y.; Yang, C.W. Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013, 382, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, V.; Modi, G.K. Getting to know the enemy better-the global burden of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2018, 94, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cockwell, P.; Fisher, L.A. The global burden of chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2020, 395, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tonelli, M.; Wiebe, N.; Culleton, B.; House, A.; Rabbat, C.; Fok, M.; McAlister, F.; Garg, A.X. Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: A systematic review. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 2034–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samoudi, A.F.; Marzouq, M.K.; Samara, A.M.; Zyoud, S.H.; Al-Jabi, S.W. The impact of pain on the quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis: A multicenter cross-sectional study from Palestine. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, R.L.; Finkelstein, F.O.; Liu, L.; Roys, E.; Kiser, M.; Eisele, G.; Burrows-Hudson, S.; Messana, J.M.; Levin, N.; Rajagopalan, S.; et al. Quality of life in chronic kidney disease (CKD): A cross-sectional analysis in the Renal Research Institute-CKD study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2005, 45, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagels, A.A.; Söderkvist, B.K.; Medin, C.; Hylander, B.; Heiwe, S. Health-related quality of life in different stages of chronic kidney disease and at initiation of dialysis treatment. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mujais, S.K.; Story, K.; Brouillette, J.; Takano, T.; Soroka, S.; Franek, C.; Mendelssohn, D.; Finkelstein, F.O. Health related quality of life in CKD Patients: Correlates and evolution over time. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nixon, A.C.; Wilkinson, T.J.; Young, H.M.L.; Taal, M.W.; Pendleton, N.; Mitra, S.; Brady, M.E.; Dhaygude, A.P.; Smith, A.C. Symptom-burden in people living with frailty and chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xie, L.; Yang, J.; Pang, X. Symptom burden amongst patients su_ering from end-stage renal disease and receiving dialysis: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 5, 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Kader, K.; Unruh, M.L.; Weisbord, S.D. Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuasuwan, A.; Pooripussarakul, S.; Thakkinstian, A.; Ingsathit, A.; Pattanaprateep, O. Comparisons of quality of life between patients underwent peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Elsurer, R.; Covic, A.; Kanbay, M. Vascular access type, health-related quality of life, and depression in hemodialysis patients: A preliminary report. J. Vasc. Access 2012, 13, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Stevens, P.E.; Bilous, R.W.; Coresh, J.; De Francisco, A.L.M.; De Jong, P.E.; Griffith, K.E.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Iseki, K.; Lamb, E.J.; et al. Kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2013, 3, 1–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, J.; Han, D. Health-Related Quality of Life Based on Comorbidities Among Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2020, 11, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Untas, A.; Thumma, J.; Rascle, N.; Rayner, H.; Mapes, D.; Lopes, A.A.; Fukuhara, S.; Akizawa, T.; Morgenstern, H.; Robinson, B.M.; et al. The associations of social support and other psychosocial factors with mortality and quality of lie in the Dialysis outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molsted, S.; Wendelboe, S.; Flege, M.M.; Eidemak, I. The impact of marital and socioeconomic status on quality of life and physical activity in patients with chronic kidney disease. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 2577–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick-Makaroff, K.; Molzahn, A.E.; Kalfoss, M. Symptoms, Coping, and Quality of Life of People with Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2018, 45, 339–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltsouda, A.; Skapinakis, P.; Damigos, D.; Ikonomou, M.; Kalaitzidis, R.; Mavreas, V.; Siamopoulos, K.C. Defensive coping and health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2011, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Chadban, S.; Walker, R.G.; Harris, D.C.; Carter, S.M.; Hall, B.; Hawley, C.; Craig, J.C. Patients’ experiences and perspectives of living with CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 53, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapes, D.L.; Lopes, A.A.; Satayathum, S.; McCullough, K.P.; Goodkin, D.A.; Locatelli, F.; Fukuhara, S.; Young, E.W.; Kurokawa, K.; Saito, A.; et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Kidney Int. 2003, 64, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Batterham, R.W.; Hawkins, M.; Collins, P.A.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R.H. Health literacy: Applying current concepts to improve health services and reduce health inequalities. Public Health 2016, 132, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.A.; Mor, M.K.; Shields, A.M.; Sevick, M.A.; Palevsky, P.M.; Fine, M.J.; Arnold, R.M.; Weisbord, S.D. Prevalence and demographic and clinical associations of health literacy in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 1354–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, D.M.; Fraser, S.D.S.; Bradley, J.A.; Bradley, C.; Draper, H.; Metcalfe, W.; Oniscu, G.C.; Tomson, C.R.V.; Ravanan, R.; Roderick, P.J.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Prevalence and Associations of Limited Health Literacy in CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 1070–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dodson, S.; Osicka, T.; Huang, L.; McMahon, L.P.; Roberts, M.A. Multifaceted Assessment of Health Literacy in People Receiving Dialysis: Associations With Psychological Stress and Quality of Life. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stømer, E.U.; Wahl, K.A.; Gøransson, G.L.; Urstad, H.K. Health literacy in kidney disease: Associations with quality of life and adherence. J. Ren. Care 2020, 46, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoumalova, I.; Madarasova Geckova, A.; Rosenberger, J.; Majernikova, M.; Kolarcik, P.; Klein, D.; de Winter, A.F.; van Dijk, J.P.; Reijneveld, S.A. Health-related quality of life profiles in dialyzed patients with varying health literacy. A cross-sectional study on Slovak haemodialyzed population. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 585801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Wolf, M.S. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am. J. Health Behav. 2007, 31, S19–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayah, F.A.; Qiu, W.; Johnson, J.A. Health literacy and health-related quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes: A longitudinal study. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, C.A.; Rincon, M. Impact of health literacy on longitudinal asthma outcomes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcelli, D.; Kirchgessner, J.; Amato, C.; Steil, H.; Mitteregger, A.; Moscardò, V.; Carioni, C.; Orlandini, G.; Gatti, E. EuCliD (European Clinical Database): A database comparing different realities. J. Nephrol. 2001, 14, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, R.D.; Kallich, J.D.; Mapes, D.L.; Coons, S.J.; Carter, W.B. Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual. Life Res. 1994, 3, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioncoloni, D.; Innocenti, I.; Bartalini, S.; Santarnecchi, E.; Rossi, S.; Rossi, A.; Ulivelli, M. Individual factors enhance poor health-related quality of life outcome in multiple sclerosis patients. Significance of predictive determinants. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 345, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, H.; Sugita, I.; Tachi, T.; Esaki, H.; Yoshida, A.; Kanematsu, Y.; Noguchi, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ichikawa, E.; Tsuchiya, T.; et al. The Relationship Between Dialysis Patients’ Quality of Life and Caregivers’ Quality of Life. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G.R.; Sloan, J.A.; Wyrwich, K.W. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med. Care 2003, 41, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolarcik, P.; Cepova, E.; Madarasova Geckova, A.; Elsworth, G.R.; Batterham, R.W.; Osborne, R.H. Structural properties and psychometric improvements of the Health Literacy Questionnaire in a Slovak population. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, R.H.; Batterham, R.W.; Elsworth, G.R.; Hawkins, M.; Buchbinder, R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoumalova, I.; Madarasova Geckova, A.; Rosenberger, J.; Majernikova, M.; Kolarcik, P.; Klein, D.; Winter, A.F.; van Dijk, J.P.; Reijneveld, S.A. Does Depression and Anxiety Mediate the Relation between Limited Health Literacy and Diet Non-Adherence? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 23.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, L.D.; Griffin, J.M.; Partin, M.R.; Noorbaloochi, S.; Grill, J.P.; Snyder, A.; Vanryn, M. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaper, M.S.; Reijneveld, S.A.; van Es, F.D.; de Zeeuw, J.; Almansa, J.; Koot, J.A.R.; de Winter, A.F. Effectiveness of a comprehensive health literacy consultation skills training for undergraduate medical students: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaper, M.S.; de Winter, A.F.; Bevilacqua, R.; Giammarchi, C.; McCusker, A.; Sixsmith, J.; Koot, J.A.R.; Reijneveld, S.A. Positive outcomes of a comprehensive health literacy communication training for health professionals in three European countries: A multi-centre pre-post intervention study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Patients Characteristics | Total Sample n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |

| Male gender | 241 (58.4%) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 64.8 ± 13.7 |

| Baseline clinical data | |

| Venous catheter | 112 (27.3%) |

| Insufficient dialysis effectiveness | 82 (20.1%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean ± SD) | 6.8 ± 2.9 |

| Health literacy | |

| Low | 128 (31.0%) |

| Moderate | 221 (53.5%) |

| High | 64 (15.5%) |

| HRQoL at baseline 1 | |

| Lower physical HRQoL | 296 (71.7%) |

| Lower mental HRQoL | 130 (31.5%) |

| Change in HRQoL 2 | |

| Deteriorated physical HRQoL | 204 (49.4%) |

| Deteriorated mental HRQoL | 169 (40.9%) |

| Model 1 (Crude) | Model 2 (Adjusted) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower HRQoL at Baseline | Lower HRQoL at Baseline | |||

| physical | mental | physical | mental | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Health literacy | ||||

| Low | 2.60 (1.33–5.10) ** | 2.98 (1.43–6.27) ** | 2.59 (1.30–5.32) ** | 2.95 (1.39–6.23) ** |

| Moderate | 1.32 (0.74–2.36) | 2.23 (1.10–4.54) * | 1.34 (0.72–2.48) | 2.16 (1.06–4.41) * |

| High | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Model 1 (Crude) | Model 2 (Adjusted) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deteriorated HRQoL | Deteriorated HRQoL | |||

| physical | mental | physical | mental | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Health literacy | ||||

| Low | 1.13 (0.62–2.07) | 1.07 (0.58–1.96) | 0.93 (0.49–1.75) | 0.88 (0.46–1.67) |

| Moderate | 1.00 (0.57–1.74) | 0.98 (0.56–1.74) | 0.91 (0.51–1.62) | 0.90 (0.50–1.63) |

| High | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Model 1 (Crude) | Model 2 (Adjusted) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deteriorated HRQoL | Deteriorated HRQoL | |||

| physical | mental | physical | mental | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Health literacy | ||||

| Low | 1.00 (0.49–2.07) | 0.86 (0.38–1.94) | 0.87 (0.41–1.85) | 0.70 (0.30–1.64) |

| Moderate | 1.12 (0.58–2.17) | 1.15 (0.56–2.39) | 1.02 (0.52–2.02) | 1.07 (0.50–2.27) |

| High | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skoumalova, I.; Madarasova Geckova, A.; Rosenberger, J.; Majernikova, M.; Kolarcik, P.; Klein, D.; de Winter, A.F.; van Dijk, J.P.; Reijneveld, S.A. Health Literacy and Change in Health-Related Quality of Life in Dialysed Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020620

Skoumalova I, Madarasova Geckova A, Rosenberger J, Majernikova M, Kolarcik P, Klein D, de Winter AF, van Dijk JP, Reijneveld SA. Health Literacy and Change in Health-Related Quality of Life in Dialysed Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2):620. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020620

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkoumalova, Ivana, Andrea Madarasova Geckova, Jaroslav Rosenberger, Maria Majernikova, Peter Kolarcik, Daniel Klein, Andrea F. de Winter, Jitse P. van Dijk, and Sijmen A. Reijneveld. 2022. "Health Literacy and Change in Health-Related Quality of Life in Dialysed Patients" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 2: 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020620

APA StyleSkoumalova, I., Madarasova Geckova, A., Rosenberger, J., Majernikova, M., Kolarcik, P., Klein, D., de Winter, A. F., van Dijk, J. P., & Reijneveld, S. A. (2022). Health Literacy and Change in Health-Related Quality of Life in Dialysed Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020620