Assessment and Management of Obesity and Self-Maintenance (AMOS): An Evaluation of a Rural, Regional Multidisciplinary Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

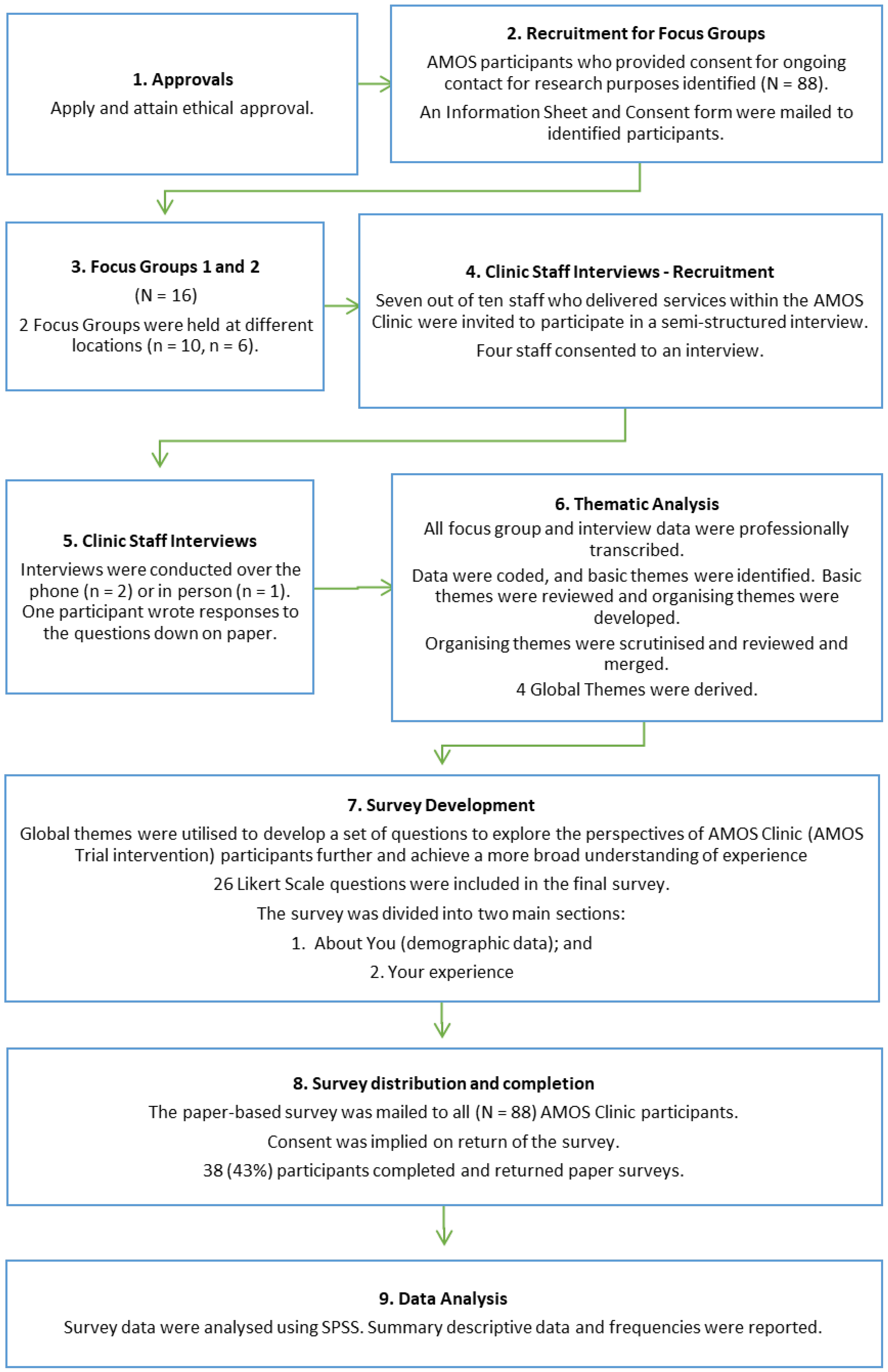

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.3.1. Focus Groups (Participants)

2.3.2. Surveys (Participants)

2.3.3. Interviews (Clinic Staff)

2.4. Method

2.4.1. Focus Groups

- How was your overall experience with the clinic?

- What do you see as some of the barriers to successful self-care for you, and what makes it easy?

- Were there times when you felt more supported in your care to feel hopeful and more confident to act for your own health and well-being.

- What, if any, were the elements that made you feel less supported or less confident?

- Did you feel as though you were being included in the decisions that were made about your care?

- If yes, how?

- If not, why not, and what would shared decision making look like to you? How would you like to be included in decisions around your care

- What is the personal and health-related value of the clinic for you?

- Do you feel that your experience in the clinic had any effect on your own diabetes and obesity management?

- Do you feel that your experience in the clinic had any effect on any other health outcomes/issues?

2.4.2. Surveys

2.4.3. Interviews

- How was your overall experience with the clinic?

- What do you see as some of the barriers to successful self-care for your patients, and what makes it easy?

- Did you feel supported in your role in the clinic?

- Do you feel that the clinic contributed to your patient’s overall health and well-being?

- Did you feel as though there was an element of shared decision making during the clinic?

- If yes, how?

- If not, why not, and what would shared decision making look like to you? How do you think they would like to be included in decisions around their care?

- Do you feel that your experience in the clinic had any effect on your own practice around diabetes and obesity management?

2.5. Analysis

2.5.1. Focus Groups and Interviews

2.5.2. Surveys

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.1.1. Focus Groups (Patient Participants)

3.1.2. Surveys (Patient Participants)

3.1.3. Interviews (Clinic Staff)

3.2. Themes from Focus Groups and Interviews

3.2.1. Theme 1: Affordability

“It was a holistic approach to care”(Participant 1);

“The whole package was brilliant”(Participant 13);

“Definitely recommend it for the support”(Participant 2);

“One of the biggest things is finding out that you are not alone”(Participant 13);

“AMOS is a one stop shop. Convenient, paid for, all done in one visit”(Participant 1).

“The facilities were great—depression is part of the diabetes story”(Participant 2);

“I joined to learn new exercises and get moving. Getting motivated”(Participant 5).

“I joined for similar reason, it could help and will not hurt and its free”(Participant 11);

“There are no free podiatry clinics for diabetes. It is hard on a pensioner”(Participant 5);

“It is hard to eat the right stuff—low calorie food is expensive”(Participant 7);

“Money is the main barrier to self-care outside the clinic”(Participant 3).

“Access to free or low-cost healthcare is absolutely motivating for people”(Staff 1);

“In regional areas, people who are bulk billed always turn up and put in the work”(Staff 1).

3.2.2. Theme 2: Multidisciplinary Care

“There were lots of services… having all of those specialties makes you feel more supported”(Participant 12);

“It was good having other specialties such as dietitian and exercise, but the forms were rotten”(Participant 7);

“I was given pamphlets on meals, but an individualised meal plan would have been more useful”(Participant 4).

“I think the patients valued the ‘team’ approach and not having to go to differing sites to access different disciplines”(Staff 2).

3.2.3. Theme 3: Person-Centred Care

“It felt like I was being individually counselled”(Participant 2);

“This was not a one size fits all clinic, which is good. It was tailor-made”(Participant 7);

“I was able to get off insulin which has made it totally worthwhile”(Participant 7).

“Many patients felt more involved in making decisions about their health and healthcare, but some did not”(Staff 3).

“…it increased my awareness (and therefore empathy) to the complex nature of these patients’ backgrounds and the multifactorial nature of their presentation”(Staff 2);

“Barriers to self-care include people’s beliefs about themselves and their abilities…”(Staff 3);

“It is important to understand how much time needs to be put in for behaviour change”(Staff 1).

“I lost 70 kg…completely off insulin”(Participant 1);

“Insulin makes you hungry, so it is hard to lose weight. So, getting off the insulin really helped”(Participant 3).

3.2.4. Theme 4: Motivation

- Motivation to seek healthcare;

- Motivation to lose weight;

- Motivation to communicate;

- Motivation to follow a plan long-term.

“I found the regular appointments were an incentive to maintain exercise and diet”(Participant 5);

“It would be helpful if they had someone to ring and talk to over the phone anytime for information that is individualised”(Participant 15).

“It is one-on-one, and it motivates you”(Participant 2);

“AMOS kept me accountable”(Participant 13);

“I need to have goals; I need to have someone check up on me. I tend to leave things if no one is pushing me”(Participant 5).

“They are all very friendly people… They are nice. That makes you feel at ease”(Participant 12);

“I found the dietitian easy to talk to…”(Participant 5)

“It’s about finding an environment and set of exercises that the patients feel comfortable with”(Staff 2).

3.3. Findings from the Survey Aligned with Themes Identified

3.3.1. Theme 1: Affordability

3.3.2. Theme 2: Multidisciplinary Care

3.3.3. Theme 3: Person-Centred Care

3.3.4. Theme 4: Motivation

4. Discussion

4.1. Theme 1: Affordability

4.2. Theme 2: Multidisciplinary Care

4.3. Theme 3: Person-Centred Care

4.4. Theme 4: Motivation

4.5. Rural, Regional and Remote Models of Care

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schutz, D.D.; Busetto, L.; Dicker, D.; Farpour-Lambert, N.; Pryke, R.; Toplak, H.; Widmer, D.; Yumuk, V.; Schutz, Y. European practical and patient-centred guidelines for adult obesity management in primary care. Obes. Facts 2019, 12, 40–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, E.W.; Shaw, J.E. Global health effects of overweight and obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 80–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wharton, S.; Lau, D.C.; Vallis, M.; Sharma, A.M.; Biertho, L.; Campbell-Scherer, D.; Adamo, K.; Alberga, A.; Bell, R.; Boulé, N.; et al. Obesity in adults: A clinical practice guideline. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E875–E891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Impact of Overweight and Obesity as a Risk Factor for Chronic Conditions: Australian Burden of Disease Study; Australian Burden of Disease Study Series No.11. Cat. No. BOD 12. BOD; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leitner, D.R.; Frühbeck, G.; Yumuk, V.; Schindler, K.; Micic, D.; Woodward, E.; Toplak, H. Obesity and type 2 diabetes: Two diseases with a need for combined treatment strategies—EASO can lead the way. Obes. Facts 2017, 10, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, D.; Sanchez-Collins, S.; Cheskin, L.J. Multidisciplinary team–based obesity treatment in patients with diabetes: Current practices and the state of the science. Diabetes Spectr. 2017, 30, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunton, J.E.; Cheung, N.W.; Davis, T.M.E.; Zoungas, S.; Colagiuri, S. A New Blood Glucose Management Algorithm for Type 2 Diabetes: A Position Statement of the Australian Diabetes Society. 2016. Available online: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2014/201/11/new-blood-glucose-management-algorithm-type-2-diabetes-position-statement (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Bell, K.; Shaw, J.E.; Maple-Brown, L.; Ferris, W.; Gray, S.; Murfet, G.; Flavel, R.; Maynard, B.; Ryrie, H.; Pritchard, B.; et al. A position statement on screening and management of prediabetes in adults in primary care in Australia. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 164, 108188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.; Blonde, L.; Chan, J.C.; Khunti, K.; Lavalle, F.J.; Bailey, C.J.; Global partnership for effective diabetes management. The interdisciplinary team in type 2 diabetes management: Challenges and best practice solutions from real-world scenarios. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Chen, Y.; Qin, H.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Chen, P. Using multi-disciplinary teams to treat obese patients helps improve clinical efficacy: The general practitioner’s perspective. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 2571–2580. [Google Scholar]

- Semlitsch, T.; Stigler, F.L.; Jeitler, K.; Horvath, K.; Siebenhofer-Kroitzsch, A. Management of overweight and obesity in primary care—A systematic overview of international evidence-based guidelines. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, K.M.; Manning, D.A.; Julian, R.M. Multidisciplinary teams and obesity: Role of the modern patient-centered medical home. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2016, 43, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obesity Australia: The Obesity Collective. Clinical Guidelines for Overweight and Obesity. 2020. Available online: https://www.obesityaustralia.org/points-of-view/#statements (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- National Association of Clinical Obesity Services. National Framework for Clinical Obesity Services—First Edition Appendix, NACOS 2020, VIC 3926 Australia. Available online: https://www.nacos.org.au/publications/ (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- National Rural Health Commissioner. National Rural Health Commissioner—Final Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/onrhc/resources?utm_source=health.gov.au&utm_medium=callout-auto-custom&utm_campaign=digital_transformation (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Pappachan, J.M.; Viswanath, A.K. Medical management of diabesity: Do we have realistic targets? Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2017, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Diabetes Educators Association. What Is Credentialling? What Is a Credentialled Diabetes Educator. 2022. Available online: http://www.adea.com.au/credentialling/what-is-credentialling/ (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Dixon, J.B.; Browne, J.L.; Mosely, K.G.; Rice, T.L.; Jones, K.M.; Pouwer, F.; Speight, J. Severe obesity and diabetes self-care attitudes, behaviours and burden: Implications for weight management from a matched case-controlled study. Results from Diabetes MILES--Australia. Diabet. Med. 2013, 31, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Overweight and Obesity—Determinants of Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/overweight-and-obesity (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- National Rural Health Alliance. Obesity Epidemic Select Committee on Obesity Epidemic in Australia. 2018. Available online: https://www.ruralhealth.org.au/advocacy/health-conditions-and-their-management (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- National Diabetes Services Scheme. Australian Diabetes Map. 2022. Available online: https://map.ndss.com.au/#!/ (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Ryan, D.H. Guidelines for obesity management. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 45, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murfet, G.; Richardson, I.; Luccisano, S.; Kilpatrick, M. Assessment and Management of Obesity and Self-Maintenance (AMOS): Outcomes of a Multidisciplinary Clinic for People Living with Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity. In Proceedings of the Australasian Diabetes Congress, Brisbane, Australia, 8–10 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry. Trial ID: ACTRN12622000240741. 2022. Available online: https://anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=383327 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callander, E.J.; Schofield, D.J. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of falling into poverty: An observational study. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callander, E.J.; Corscadden, L.; Levesque, J.-F. Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure and chronic disease—Do Australians forgo care because of the cost? Aust. J. Prim. Health 2017, 23, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, D.; Cunich, M.M.; Shrestha, R.N.; E Passey, M.; Veerman, L.; Callander, E.J.; Kelly, S.J.; Tanton, R. The economic impact of diabetes through lost labour force participation on individuals and government: Evidence from a microsimulation model. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Wong, R.; Newberry, C.; Yeung, M.; Peña, J.M.; Sharaiha, R.Z. Multidisciplinary clinic models: A paradigm of care for management of NAFLD. Hepatology 2021, 74, 3472–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwer, D.B.; Polonsky, H.M. The psychosocial burden of obesity. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 45, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.S.; Gupta, A.; Jacobs, J.P.; Lagishetty, V.; Gallagher, E.; Bhatt, R.R.; Vora, P.; Osadchiy, V.; Stains, J.; Balioukova, A.; et al. Improvement in uncontrolled eating behavior after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is associated with alterations in the Brain–Gut–Microbiome Axis in obese women. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalarchian, M.A.; Marcus, M.D.; Levine, M.D.; Courcoulas, A.P.; Pilkonis, P.A.; Ringham, R.M.; Soulakova, J.N.; Weissfeld, L.A.; Rofey, D.L. Psychiatric disorders among bariatric surgery candidates: Relationship to obesity and functional health status. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmisano, G.L.; Innamorati, M.; Vanderlinden, J. Life adverse experiences in relation with obesity and binge eating disorder: A systematic review. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane, A.J.; Dick, B.; King, N.A.; Hills, A.P.; Kavanagh, D.J. Developing dimensions for a multicomponent multidisciplinary approach to obesity management: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturgiss, E.; Jay, M.; Campbell-Scherer, D.; van Weel, C. Challenging assumptions in obesity research. BMJ 2017, 359, j5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, K.; Barr, J.; Rossetto, G.; Mercer, J. A “messy ball of wool”: A qualitative study of the dimensions of the lived experience of obesity. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.; Wolf, C.; Labbé, S.; Peterson, E.; Murray, S. Primary health care providers’ roles and responsibilities: A qualitative exploration of ‘who does what’ in the treatment and management of persons affected by obesity. J. Commun. Health 2017, 10, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Diabetes Society, the Australian and New Zealand Obesity Society and the Obesity Surgery Society of Australian and New Zealand. The Australian Obesity Management Algorithm. 2016. Available online: https://www.diabetessociety.com.au/position-statements.asp (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Rueda-Clausen, C.; Benterud, E.; Bond, T.; Olszowka, R.; Vallis, M.T.; Sharma, A.M. Effect of implementing the 5As of obesity management framework on provider-patient interactions in primary care: 5As of obesity management in primary care. Clin. Obes. 2013, 4, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, E.A.; Ramirez, M.L.; Haltzman, B.; Fritz, M.; Kozak, A.T. Patient’s experience with comorbidity management in primary care: A qualitative study of comorbid pain and obesity. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2015, 17, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, S.F.L.; Price, S.; Penney, T.L.; Rehman, L.; Lyons, R.F.; Piccinini-Vallis, H.; Vallis, M.; Curran, J.; Aston, M. Blame, shame, and lack of support: A multilevel study on obesity management. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, S.L.; Wischenka, D.; Appelhans, B.M.; Pbert, L.; Wang, M.; Wilson, D.K.; Pagoto, S.L.; Society of behavioral medicine. An evidence-based guide for obesity treatment in primary care. Am. J. Med. 2015, 129, 115.e1–115.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesi, L.; El Ghoch, M.; Brodosi, L.; Calugi, S.; Marchesini, G.; Dalle Grave, R. Long-term weight loss maintenance for obesity: A multidisciplinary approach. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2016, 9, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueland, V.; Furnes, B.; Dysvik, E.; Rørtveit, K. Living with obesity—Existential experiences. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2019, 14, 1651171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, B.; Borge, L.; Fagermoen, M.S. Understanding everyday life of morbidly obese adults-habits and body image. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2012, 7, 17255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surrow, S.; Jessen-Winge, C.; Ilvig, P.M.; Christensen, J.R. The motivation and opportunities for weight loss related to the everyday life of people with obesity: A qualitative analysis within the DO:IT study. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 28, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, R.T.; Schneider, K.L.; Yalla, S.V.; Reeves, N.D.; Vileikyte, L. Physiological and psychological challenges of increasing physical activity and exercise in patients at risk of diabetic foot ulcers: A critical review. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, Y.A.; Jansen, H.J.; Hopman, M.T.; Tack, C.J.; Thijssen, D.H. Insulin-associated weight gain in type 2 diabetes is associated with increases in sedentary behavior. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, e120–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pi-Sunyer, F.X. Weight loss in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1526–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Rural Health Alliance. National Rural Health Alliance—2021–22 Pre-Budget Submission. 2021. Available online: https://www.ruralhealth.org.au/document/national-rural-health-alliance-2021-22-pre-budget-submission (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Scottish Government. Models of Multi-Disciplinary Team Working in Rural Primary Care: An International Review—Report to the Remote and Rural General Practice Working Group, November 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/models-multidisciplinary-working-international-review/pages/4/ (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Department of Health. Australian National Strategic Framework for Rural and Remote Health. 2016. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/national-strategic-framework-rural-remote-health (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Commonwealth of Australia. The National Obesity Strategy 2022–2032. Health Ministers Meeting. 2022. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-obesity-strategy-2022-2032 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Not Sure | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I joined AMOS for the free weight management services | 9 (27%) | 8 (24%) | 11 (33%) | 2 (6%) | 3 (9%) | 5 |

| I joined AMOS for the free specialist diabetes services | 13 (39%) | 14 (42%) | 5 (15%) | 1 (3%) | 0 | 5 |

| I joined AMOS for the free psychology services | 6 (18%) | 5 (15%) | 15 (44%) | 4 (12%) | 4 (12%) | 4 |

| I joined AMOS for the free physiotherapy services | 5 (15%) | 6 (18%) | 15 (44%) | 4 (12%) | 4 (12%) | 4 |

| I joined AMOS for the free dietitian services | 8 (24%) | 12 (35%) | 8 (24%) | 4 (12%) | 2 (6%) | 4 |

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Not Sure | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMOS supported me to learn to take care of my body | 14 (40%) | 19 (54%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (6%) | 2 |

| AMOS provided a supportive team | 16 (46%) | 17 (49%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (6%) | 0 |

| My mental health was looked after by the AMOS team (or clinic) | 11 (31%) | 12 (34%) | 3 (9%) | 0 | 9 (26%) | 2 |

| I felt nervous or anxious about not having support after the AMOS Clinic | 5 (16%) | 2 (6%) | 13 (41%) | 3 (9%) | 9 (28%) | 5 |

| There was good communication between AMOS and my GP about diagnostic tests | 11 (33%) | 15 (45%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 4 (12%) | 4 |

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Not Sure | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Because of my experience with the AMOS Clinic, I feel that I am able to make the right changes to keep improving my health | 6 (18%) | 21 (62%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 5 (15%) | 3 |

| I felt safe in the AMOS Clinic | 16 (47%) | 17 (50%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) | 2 |

| I have been able to maintain any weight loss since the AMOS Clinic | 7 (21%) | 11 (32%) | 10 (29%) | 1 (3%) | 5 (15%) | 3 |

| The AMOS Clinic helped me get my diabetes under control | 16 (46%) | 10 (29%) | 1 (3%) | 0 | 8 (23%) | 3 |

| I have been able to keep my diabetes under control since the AMOS Clinic | 9 (26%) | 18 (51%) | 2 (6%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (11%) | 3 |

| Because of my experience with the AMOS Clinic, my medication changes were successful | 13 (37%) | 11 (31%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 8 (23%) | 3 |

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Not Sure | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMOS motivated me to look after my overall health and well-being | 11 (31%) | 20 (57%) | 2 (6%) | 0 | 2 (6%) | 3 |

| My GP was supportive of me being involved in the AMOS Clinic | 13 (38%) | 13 (38%) | 3 (9%) | 2 (6%) | 3 (9%) | 4 |

| The AMOS Clinic helped me lose weight | 13 (37%) | 15 (43%) | 3 (9%) | 0 | 4 (11%) | 3 |

| I would recommend the AMOS Clinic to other people who struggle with weight issues | 22 (63%) | 12 (34%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) | 3 |

| I joined AMOS because I had no success managing my diabetes on my own in the past | 5 (14%) | 16 (46%) | 8 (23%) | 0 | 6 (17%) | 3 |

| I joined AMOS because I have had no weight loss success on my own in the past | 9 (26%) | 7 (20%) | 12 (34%) | 0 | 7 (20%) | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prior, S.J.; Luccisano, S.P.; Kilpatrick, M.L.; Murfet, G.O. Assessment and Management of Obesity and Self-Maintenance (AMOS): An Evaluation of a Rural, Regional Multidisciplinary Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12894. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912894

Prior SJ, Luccisano SP, Kilpatrick ML, Murfet GO. Assessment and Management of Obesity and Self-Maintenance (AMOS): An Evaluation of a Rural, Regional Multidisciplinary Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12894. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912894

Chicago/Turabian StylePrior, Sarah J., Sharon P. Luccisano, Michelle L. Kilpatrick, and Giuliana O. Murfet. 2022. "Assessment and Management of Obesity and Self-Maintenance (AMOS): An Evaluation of a Rural, Regional Multidisciplinary Program" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12894. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912894

APA StylePrior, S. J., Luccisano, S. P., Kilpatrick, M. L., & Murfet, G. O. (2022). Assessment and Management of Obesity and Self-Maintenance (AMOS): An Evaluation of a Rural, Regional Multidisciplinary Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12894. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912894