Pandemic COVID-19 Influence on Adult’s Oral Hygiene, Dietary Habits and Caries Disease—Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

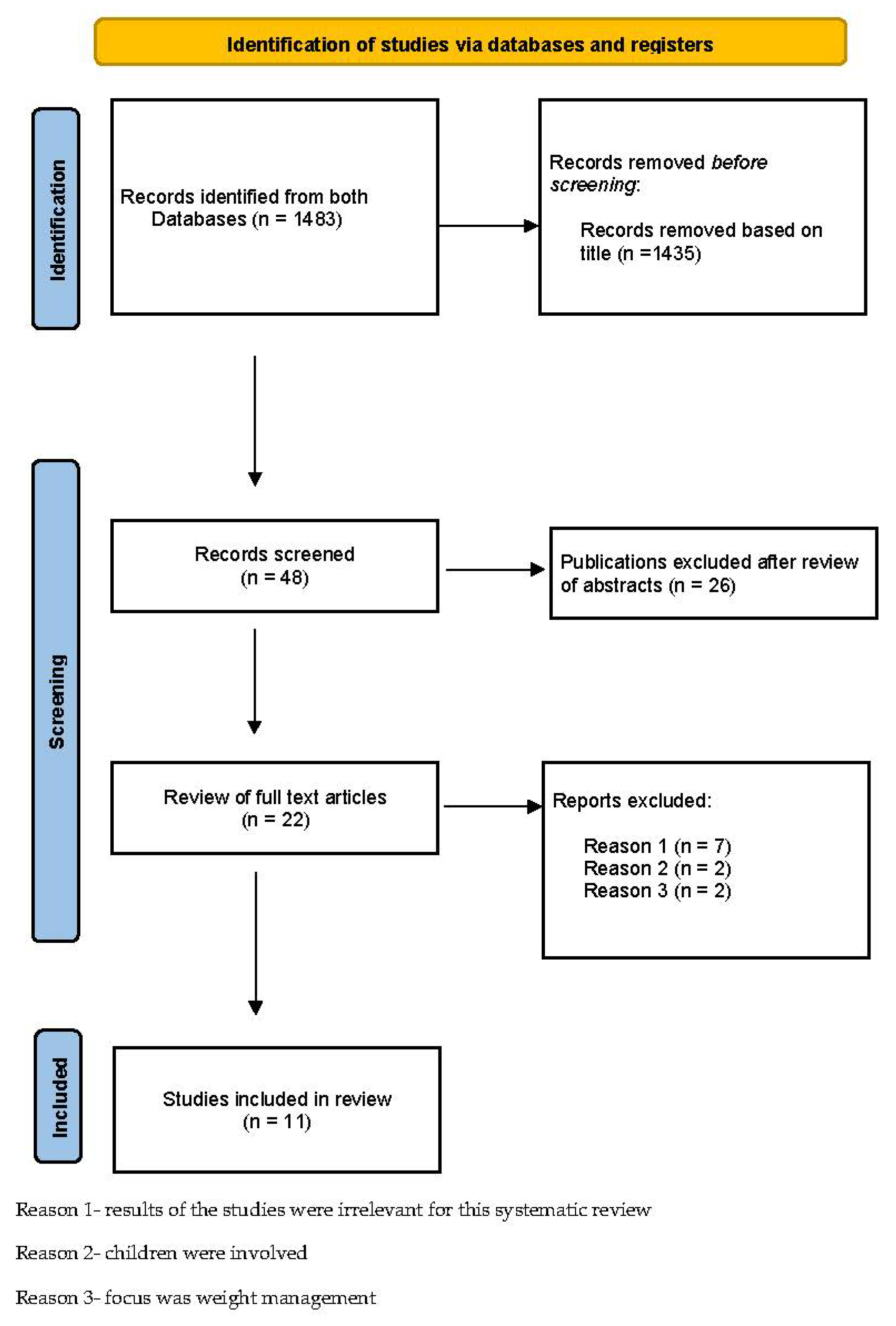

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Assessment of Quality of Study

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

3.3. Attributes of the Studies

3.4. Impact of COVID-19 on Dietary Habits

3.5. Impact of COVID-19 on Oral Hygiene Habits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Wen, P.Y.F.; Chen, M.X.; Zhong, Y.J.; Dong, Q.Q.; Wong, H.M. Global Burden and Inequality of Dental Caries, 1990 to 2019. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwitz, R.H.; Amid, I.; Nigel, P.B. Dental caries. Lancet 2007, 369, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove, J.M. Dental plaque revisited: Bacteria associated with periodontal disease. J. N. Z. Soc. Periodontol. 2004, 87, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kinane, D.; Stathopoulou, P.; Papapanou, P. Periodontal diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y. Diagnosis and Prevention Strategies for Dental Caries. J. Lifestyle Med. 2013, 3, 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Algren, M.H.; Ekholm, O.; Nielsen, L.; Ersbøll, A.K.; Bak, C.K.; Andersen, P.T. Social isolation, loneliness, socioeconomic status, and health-risk behaviour in deprived neighbourhoods in Denmark: A cross-sectional study. SSM—Popul. Health 2020, 10, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71 (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Paltrinieri, S.; Bressi, B.; Costi, S.; Mazzini, E.; Cavuto, S.; Ottone, M.; De Panfilis, L.; Fugazzaro, S.; Rondini, E.; Giorgi Rossi, P. The Potential Side Effects of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic on Public Health. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, A.; Sospedra, I.; Martínez-Sanz, J.M.; Gutierrez-Hervas, A.; Fernández-Saez, J.; Hurtado-Sánchez, J.A.; Norte, A. Assessment of Spanish Food Consumption Patterns during COVID-19 Home Confinement. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszynska, E.; Cofta, S.; Hernik, A.; Otulakowska-Skrzynska, J.; Springer, D.; Roszak, M.; Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Self-Reported Dietary Choices and Oral Health Care Needs during COVID-19 Quarantine: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, S.F.S.; Costa, F.O.; Pereira, A.G.; Cota, L.O.M. Self-perceived and self-reported breath odour and the wearing of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oral Dis. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, G.; Camussi, E.; Piccinelli, C.; Senore, C.; Armaroli, P.; Ortale, A.; Garena, F.; Giordano, L. Did social isolation during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic have an impact on the lifestyles of citizens? Epidemiol. Prev. 2020, 44 (Suppl. S2), 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotnicka, M.; Karwowska, K.; Kłobukowski, F.; Wasilewska, E.; Małgorzewicz, S. Dietary Habits before and during the COVID-19 Epidemic in Selected European Countries. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, T.C.; Oliveira, L.A.; Daniel, M.M.; Ferreira, L.G.; della Lucia, C.M.; Liboredo, J.C.; Anastácio, L.R. Lifestyle and eating habits before and during COVID-19 quarantine in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 25, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.; Fogacci, F.; Giovannini, M.; Mezzadri, M.; Grandi, E.; Borghi, C. COVID-19-Related Quarantine Effect on Dietary Habits in a Northern Italian Rural Population: Data from the Brisighella Heart Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzan-Vercelino, C.; Freitas, K.; Girão, V.; da Silva, D.; Peloso, R.; Pinzan, A. Does the use of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic impact on oral hygiene habits, oral conditions, reasons to seek dental care and esthetic concerns? J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2021, 13, e369–e375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, A.; Bilmez, Z.Y. Effects of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Fear on Oral Health Status. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2021, 19, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cărămidă, M.; Dumitrache, M.A.; Țâncu, A.M.C.; Ilici, R.R.; Ilinca, R.; Sfeatcu, R. Oral Habits during the Lockdown from the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in the Romanian Population. Medicina 2022, 58, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayaty, F.H.; Baharudin, N.; Hassan, M.I.A. Impact of dental plaque control on the survival of ventilated patients severely affected by COVID-19 infection: An overview. Dent. Med. Probl. 2021, 58, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradowska-Stolarz, A.M. Oral manifestations of COVID-19: Brief review. Dent. Med. Probl. 2021, 58, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuno-Gonzalez, A.; Martin-Carrillo, P.; Magaletsky, K.; Martin Rios, M.D.; Herranz Mañas, C.; Artigas Almazan, J.; García Casasola, G.; Perez Castro, E.; Gallego Arenas, A.; Mayor Ibarguren, A.; et al. Prevalence of mucocutaneous manifestations in 666 patients with COVID-19 in a field hospital in Spain: Oral and palmoplantar findings. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, M.; Partyka, M.; Romanowska, P.; Saczuk, K.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M.M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the dental service: A narrative review. Dent. Med. Probl. 2021, 58, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberoğlu, B.; Koç, N.; Boyacioglu, H.; Akçiçek, G.; İriağaç, Ş.; Doğan, Ö.B.; Özgüven, A.; Zengin, H.Y.; Dural, S.; Avcu, N. Assessment of dental anxiety levels among dental emergency patients during the COVID-19 pandemic through the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale. Dent. Med. Probl. 2021, 58, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lages, F.S.; Douglas-de-Oliveira, D.W. Effect of social isolation on oral healthstatus—A systematic review. Community Dent. Health 2022, 39, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Components | Response options | |||

| 1. Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 2. Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 3. Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 4. Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 5. Were confounding factors identified? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 6. Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 7. Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 8. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| Total | 8 points | |||

| Study | Ferrante G. et al., 2020 [12] | Skotnicka M. et al., 2021 [13] | Maestre A. et al., 2021 [9] | Souza TC. et al., 2021 [14] | Paltrinieri S. et al., 2021 [8] | Cicero, A. et al., 2021 [15] | Pinzan-Vercelino, C. et al., 2020 [16] | Sari a. et al., 2021 [17] | Faria SFS et al., 2021 [11] | Paszynska, E. et al., 2021 [10] | Cărămidă M. et al., 2022 [18] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| 6 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Total | 4/8 | 5/8 | 6/8 | 5/8 | 7/8 | 5/8 | 5/8 | 5/8 | 4/8 | 5/8 | 5/8 |

| Author, Year, Country | Design | Duration of Study | Population | Age of Study Group, Sex | Number of Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrante G. et al., 2020, Italy [13] | Cross-sectional study | 21 April 2020–7 June 2020 | Internet responders | 14–70+, female and male | 7847 |

| Skotnicka M. et al., 2021, Poland [14] | Cross-sectional study | 1 October 2020–30 October 2020 | Internet responders | >18, Female and male | 1071 |

| Maestre A. et al., 2021, Spain [10] | Cross-sectional study | 1 April 2020–4 May 2020 | Internet responders | >18, Female and male | 1640 |

| Souza TC. et al., 2021, Brazil [15] | Cross-sectional study | from August 2020 to September 2020 | Internet responders | >18, Female and male, excluding pregnant women | 1368 |

| Paltrinieri S. et al., 2021, Italy [9] | Cross-sectional study | 4 May 2020–15 June 2020 | Internet responders | >18, Female and male | 1826 |

| Cicero, A. et al., 2021 Italy [16] | Sub-study of a longitudinal population study | February 2020–April 2020 | Phone Interview Responders | >18, Female and male | 359 |

| Pinzan-Vercelino, C. et al., 2020, Brazil [17] | Cross-sectional study | 10 June 2020–20 June 2020 | Electronic survey (Google Forms) | >18, Female and male, wearing face masks in the last 30 days | 1346 |

| Sari a. et al., 2021, Turkey [18] | Cross-sectional study | 1 August 2020–1 October 2020 | Online survey via email/WhatsApp | >18 and <65, Female and male | 1227 |

| Faria SFS et al., 2021, Brazil [12] | Cross-sectional study | August 2020 | Email questionnaire | Members and staff of Federal University of Minas Geiras | 4647 |

| Paszynska, E. et al., 2021, Poland [11] | Cross-sectional study | March 2021–May 2021 | Self-designed questionnaire conducted at the COVID-19 Vaccination point | >18, Female and male, COVID vaccinated individuals | 2574 |

| Cărămidă M. et al., 2022, Romania [19] | Cross-sectional study | May 2020 | Questionnaire distributed via digital platforms | 18–75, Medical professionals and the general population | 800 |

| Author | Aim of the study | Form | Tools | Variables | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrante G. et al. [13] | to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on daily habits | -25 questions about eating and smoking habits | online self-report questionnaire | -nutrition -alcohol intake - smoking | -among smokers 30% reported an increase in the number of cigarettes smoked per day -the increase in alcohol consumption was reported by 17.3% of respondents -the number of responders who increased sweets intake (45%) is almost three-fold that of those who reduced them (16.5%) | -lack of representativeness of the considered sample -all data collected are self-reported = not completely reliable -small number of interviews (14%) was collected after May 3rd, the date marking the end of the most rigid period of social isolation |

| Skotnicka M. et al. [14] | to examine changes in dietary habits during COVID-19 | - 0 questions about dietary habits | online self-report questionnaire | -sweets and snacks, juice and sweets drinks consumption -alcohol intake | -5.61% increase of sweets consumption -9.81 % increase of alcohol consumption -0.65% decrease of juice and sweet drinks consumption | -were not mentioned |

| Maestre A. et al. [10] | to identify the main changes in the eating habits during COVID-19 | Modified Food consumption frequency questionnaire (FFQ) consisting of 18 questions | online self-report questionnaire | -sweets and candy consumption -snacks consumption -sugary sodas intake | Consumption’s Increase of: -sweets and candy = 32.7% -Snacks = 5.9% -sugary sodas = 28.2% --- > worsening of the dietary patterns of the population with an increase in the frequency of consumption of snacks and products rich in sugars | -telematic sampling system (over- and under-estimation possibility) -all data collected are self-reported = not completely reliable -more than 65% of the sample belonged to the Valencian Community- lack of representativeness of the considered sample -BMI biases possible |

| Souza TC. et al. [15] | to assess changes in food choices of adult Brazilians before and during the COVID-19 pandemic | Modified Food consumption frequency questionnaire (FFQ) consisting of 18 Questions | online self-report questionnaire | -alcohol consumption -frequency of smoking | -increase in the frequency of consumption of alcoholic beverages, but a reduction in the dose -increase in the frequency of smoking, but no significant difference in the number of cigarettes smoked per day | -all data collected are self-reported = not completely reliable -habits before the pandemic could possibly not be exactly remembered |

| Paltrinieri S. et al. [9] | to describe the changes in diet, alcohol drinking, and cigarette smoking during lockdown | -49 questions about dietary habits | online self-report questionnaire | -sweets and candy consumption -snacks consumption -sugary sodas intake -alcohol consumption -frequency of smoking | -diet changes in 17.6% of cases were for the worse (eating more snacks, sweets, carbonated drinks), in 33.5% improved (paying more attention to eating healthier) -in alcohol drinking changes occurred in both directions equally, since 12.5% of individuals increased their alcohol consumption and 12.6% decreased it -7.7% of smokers reported an increase and 4.1% a decrease in cigarette smoking | -sample was not representative of the resident population -self-perceived phenomena -age, sex, and education level as possible sources of bias |

| Cicero A. et al. [16] | to evaluate the effect of COVID-related quarantine on smoking and dietary habits | The Dietary Quality Index (DQI), a validated tool providing information on the usual food intake of 18 food items, grouped into three food categories | phone Interview | -sweets and sugar intake -alcoholic drinks intake -smoking frequency | -during quarantine, the interviewed subjects significantly increased the consumption of simple sugars, added fats, and alcohol, while overall increasing the carbohydrates and fat intake -quarantine did not significantly modify smoking habit (2.2% reduced their habit, 1.7% increased smoking) of respondents | -sample was not representative of the resident population -self-perceived phenomena -age, sex, and education level as possible sources of bias |

| Pinzan-Vercelino, C. et al. [17] | to evaluate the impact of the use of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic on oral hygiene habits | 41 multiple-choice questions oriented in the oral hygiene and oral conditions self-perception directions | online self-report questionnaire | -halitosis -need to seek dental care -concern about smile esthetic -frequency of teeth brushing | -10% needed to seek emergency dental care mainly due to tooth pain - the number of subjects with no concern about smile esthetics increased significantly (6.8%) -women, younger people, and subjects that had completed high school or had university or professional degrees reported more concern with smile esthetics - the subjects were brushing their teeth fewer times per day and people are less concerned about oral hygiene -the number of subjects that reported having halitosis increased significantly and there was a significant association between toothbrushing less time per day | -observations could not be directly inferred for other populations |

| Sari a. et al. [18] | to investigate the effects of COVID-19 on oral health status | total of 24 mandatory closed-ended questions | online self-report questionnaire | -frequency of teeth brushing -usage of oral care products -consumption of sugary foods -visiting dental clinics | -41.1% started brushing more regularly and 32.49% of brushing routines were disrupted -9.9% started using oral care products more regularly, while 7.3% more irregularly -33.3% increase in sugary food consumption -50.4% hesitated to go to the dentist compared to before COVID-19, and a total of 75,6% thought that dental clinics were at risk of COVID contamination. | -survey required the use of smartphones, therefore mostly young people mostly with high economic status participated -cross-sectional design |

| Faria SFS et al. [12] | to assess self-reported halitosis and oral hygiene habits with the wearing of face masks during the pandemic | questionnaire included a total of 18 items | email self-report questionnaire | -considering having a bad breath -changes in oral hygiene habits -seeking a healthcare professional | -14% of individuals started to consider having bad breath -24% increased frequency of toothbrushing, 5.8% of mouthwa use. Mainly individuals, who realized their bad breath significantly changed their oral hygiene -only 0,4% were seeking forsh a healthcare professional | -questionnaire-survey study with bias possibilities -most responders were female and limited to the university staff and students |

| Paszynska, E. et al. [11] | to assess whether the COVID-19 pandemic affected dietary choices, oral hygiene habits, and willingness to visit the dental office | questionnaire- number of questions not mentioned | self-report questionnaire | -eating frequency -smoking and alcohol consumption | -13.4% declared increased eating frequency with 19.1% sweet snack preference -only 17.3% did not report any alcohol consumption -3.4% declared smoking more than one pack a day -only 52.9% had a dental visit in 2020 -25% were afraid to schedule a dental examination | -limited access to some societal groups -limited frame of the questionnaire |

| Cărămidă M. et al. [19] | to assess differences in oral hygiene routine, smoking, and eating habits during the lockdown | online questionnaire formed of 17 items | self-report questionnaire | -frequency of toothbrushing -use of dental floss -smoking frequency -eating habits | -frequency of toothbrushing did not change, however, the time spent on toothbrushing increased in the medical professionals’ group significantly (5.2%), as well as the frequency of dental floss usage (3.5%) -sweet snacks consumption increased significantly in both groups (ca. 7%) -number of non-smokers increased in both groups (ca. 6%) | -self-reported habits with the possibility of under- or overestimation - not fully representative of the general population -only first quarantine context |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wdowiak-Szymanik, A.; Wdowiak, A.; Szymanik, P.; Grocholewicz, K. Pandemic COVID-19 Influence on Adult’s Oral Hygiene, Dietary Habits and Caries Disease—Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12744. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912744

Wdowiak-Szymanik A, Wdowiak A, Szymanik P, Grocholewicz K. Pandemic COVID-19 Influence on Adult’s Oral Hygiene, Dietary Habits and Caries Disease—Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12744. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912744

Chicago/Turabian StyleWdowiak-Szymanik, Aleksandra, Agata Wdowiak, Piotr Szymanik, and Katarzyna Grocholewicz. 2022. "Pandemic COVID-19 Influence on Adult’s Oral Hygiene, Dietary Habits and Caries Disease—Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12744. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912744

APA StyleWdowiak-Szymanik, A., Wdowiak, A., Szymanik, P., & Grocholewicz, K. (2022). Pandemic COVID-19 Influence on Adult’s Oral Hygiene, Dietary Habits and Caries Disease—Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12744. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912744