“It Made Me Feel like Things Are Starting to Change in Society:” A Qualitative Study to Foster Positive Patient Experiences during Phone-Based Social Needs Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Approach

2.2. Context, Setting, and Intervention

2.3. Sampling Strategy

2.4. Ethical Issues Pertaining to Human Subjects

2.5. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.6. Data Processing and Analysis

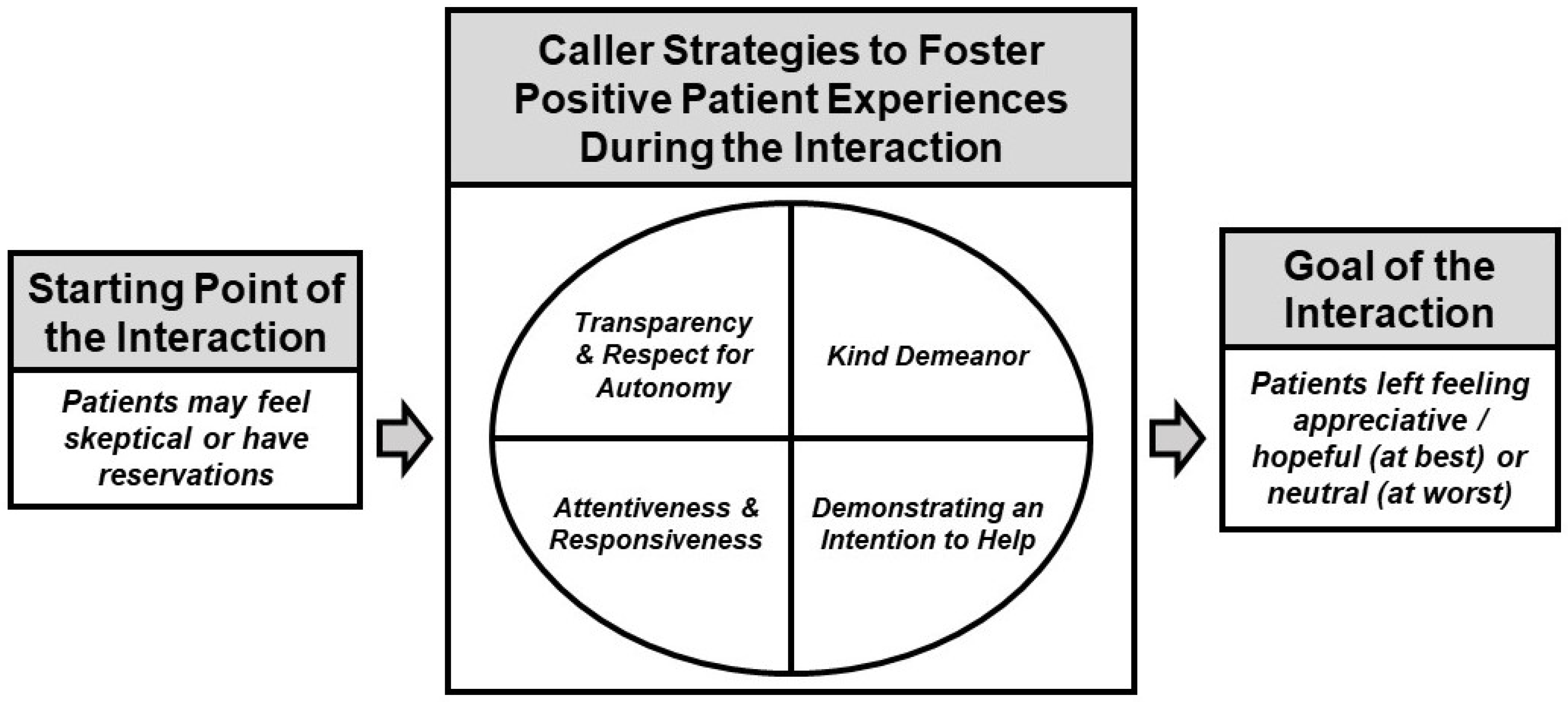

3. Results

“Some people will take that as a straight up scam, like you’re trying to track them or some shit, you know what I mean?”<25-year-old White male (a)

“I’m very inquisitive when it comes to that … At first [I ask], ‘Where are you calling me from? Why are you calling me?’ Not just anyone is going to be helping a person. Sometimes they just do it to grab your information.” (“Yo soy muy preguntona para eso … Al principio [yo digo], ‘¿De dónde me llamas? ¿Por qué me llamas?’ … No cualquiera va a estar ayudando a una persona. A veces nomás hacen por agarrar información.”)45 to 54 year-old Hispanic female

“There are people out there that need help but don’t wanna be a bother … People my age and older, you don’t take handouts, that’s embarrassing.”45 to 54-year-old White female

“[She] didn’t want things to come down to her, like, because I’m applying for assistance then they would come and look at her, like, ‘Why aren’t you giving more money or why aren’t you doing something?’ … I think [there was a concern around something like Department of Human Services (DHS) involvement] … With my daughter’s disability there was DHS involved quite a bit in our household … Maybe it would cause her more problems to admit to some of this stuff.”65 to 74-year-old White female

“It seemed like a scam at first, but because I know [the healthcare organization] and I’ve been going there since I was like two years old, I was like, ‘No, there’s no way it’s a scam.’”<25-year-old White female (a)

Interviewer: “To make sure I’m getting this right, being prepared for when the person answers to give a clear description of who you are and where you’re coming from?” Interviewee: “Right. You got it. A plus.”65 to 74-year-old Black male

“She mentioned there was going to be some personal questions and I didn’t have to answer if I didn’t want to … I appreciated that a lot.”<25-year-old White female (b)

“I mean, I don’t want to be hassled if I tell them that everything is good … If I’m not in a good place, I’ll ask them. I don’t want to be pressured or hassled.”45 to 54-year-old Black male

“It’s pretty straightforward … We all know good customer service. Be nice to people. Treat others how you’d want to be treated.”35 to 44-year-old Black male

“The tone of voice she maintained the whole time was also really helpful … Just maintaining maybe a soft, it doesn’t always have to be soft, but just like a calming [voice] … It’s very stereotypical, but it does work.”<25-year-old Hispanic female (a)

Interviewer: “How did you feel during the call?” Interviewee: “Supported.” Interviewer: “Supported. Was that because of the questions they were asking you or because of the tone of their voice or both?” Interviewee: “Because of both things.” (Entrevistadora: “¿Cómo se sintió durante esta llamada?” Entrevistada: “Apoyada.” Entrevistadora: “Apoyada. ¿Es por las preguntas que le hicieron o por el tono de voz o ambas? Entrevistada: “Por ambas.”)55 to 64-year-old Hispanic female

“She wasn’t very kind, too. Just quick and short … The tone in her voice, it seemed like she was in a big hurry … I had the feeling she didn’t have her morning coffee … There was just no life and no concern, no personal interest in what she was saying.”55 to 64-year-old White female

“As long as I think it’s gonna help me and not hurt me, I’m willing to answer questions.”45 to 54-year-old American Indian or Alaska Native female

Interviewer: “Is it okay to ask [about social needs], even when help or resources cannot be guaranteed?” Interviewee: “It depends on the person. Look, there are times when, if they are going to help you, that’s fine! But if they are one of those people who doesn’t want to help, they will not explain it to you. Interviewer: “So, more like what are the intentions [of the person]?” Interviewee: “Yes.” (Entrevistadora: “¿Está bien que se hagan este tipo de preguntas, aun cuando no es posible garantizar la ayuda o los recursos?” Entrevistado: “Depende de la persona. Mira que hay veces que, si te van a ayudar, ¡está bien! Pero si son de esas personas que no quieren ayudar, no te van a explicar. Entrevistadora: “O sea, más bien ¿cómo son las intenciones?” Entrevistado: “Ajá.”)45 to 54-year-old Hispanic male

Interviewee: “It was just very helpful … One of those things where it’s like I point out a problem [and they say] ‘Oh, there’s an issue, let’s get that taken care of.’” … Interviewer: “It sounds like you appreciated that … she had an optimistic outlook on it, but she also explained that it couldn’t be guaranteed. Like, she tried to do both of those things?” Interviewee: “Exactly. That feels more honest because you can still be optimistic without knowing that there’s a guarantee.”<25-year-old White male (b)

“If you had gotten me, say, seven months ago … it would have been significantly more difficult because I was delusional … If [a person] is so far gone that they can’t actually answer the questions, [you] just need to contact them at a later date because it’s a day-to-day thing.”—35 to 44-year-old male (the participant did not respond to the questions about race or ethnicity)

“I think [the process to try to connect me with resources] was very easy and thoughtful … She gave me a choice to do it online or by mail … So, when I was able to get it through the mail, like I requested, I could use it for future reference if I ever needed it.”55 to 64-year-old Black female

Interviewee: “Oh yeah, [having someone walk me through the paperwork was helpful]. For people like me, I have a hard time with reading and things that are pretty basic … Interviewer: “Do you think that had you not had that help, you may have not applied for the bus passes, for example?” Interviewee: “Yeah, probably, because I’m just really anxious about stuff like that, especially in regards to paperwork and legal stuff, I would have been too afraid of doing it wrong.”<25-year-old Hispanic female (b)

“Well, I told him, ‘I live in [County A], so do you [have] anything in [County A]?’ But they gave me the [number for] [County B] … That’s the problem … I don’t need [County B].”45 to 54-year-old Asian male

“I told him over and over again, ‘I don’t need all of the other stuff, the dot coms and all that crap.’ … [The resources were sent] as texts on my phone, but there weren’t phone numbers on any of them, and I don’t have a computer, or a laptop, or [know] how to do that.”55 to 64-year-old Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander female

“It’s giving so much hope and kindness … Because of COVID … because of my heart condition and health condition … I have to stay away from people, I don’t have the vaccine yet because of my heart and everything. So I’m not as social as I used to be. And some people, their lights go dim. And you guys are like the lighthouse on the beach, saying, ‘Here’s the light, I’m trying to shine it to you.’”45 to 54-year-old Multiracial female

“I was happy because it made me feel like things are starting to change in society … I really felt important and like things are starting to change.”25 to 34-year-old Hispanic female

“I don’t remember exactly, but when someone isn’t very nice to you, you would remember it … I think the person was nice. They were nice because of that, because I don’t really remember.” (“No recuerdo con exactitud, pero cuando alguien no es muy amable con uno, uno sí lo recuerda … Yo pienso que la persona fue amable. Fue amable por eso, [porque] no tengo mucho recuerdo.”)65 to 74-year-old Hispanic male

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide

- How is your health status in general? Would you say it is very good, good, relatively good, bad, or very bad?

- How would you describe your health over the last six to twelve months?

- Do you remember that call?

- What do you remember about the questions?

- How did the interaction feel to you?

- Did the questions seem relevant to your health?

- Were you surprised to get questions about these topics from [clinical delivery site]?

- What do you think about healthcare organizations asking these types of questions, in general?

- Do you have recommendations about how to ask these questions? For example, do you have a preference for being asked these questions in person or over the phone?

- That is totally fine. The questions were about things that may affect your health, like food, housing, and access to transportation.

- What do you think about healthcare organizations asking these types of questions, in general?

- Do you have recommendations about how to ask these questions?

- Did anyone follow up with you about this? If so, what do you remember about that conversation? Probes, if needed: For example, how the conversation went, what the person asked, how you felt?

- If no one followed up, do you have thoughts about that?

- If your healthcare provider offered to help you identify resources for things like food and housing, do you think you would accept their support? Why or why not?

- Were you able to access any resources through the person who followed up with you or through your own outreach?

- If so, please share a bit about the resources you received. Did you receive the resource information through the mail or electronically?

- If not, do you have thoughts about that?

- Are you still facing any of the same problems you were experiencing before?

- Are you okay with healthcare organizations asking about these types of things, even if they are not able to resolve the problem?

- Do you have any recommendations for how to make community resource referrals smoother for patients?

- Have you tried to access community resources like these before? Why or why not?

- Are you okay with healthcare organizations asking about these types of things, even if they are not able to resolve the problem?

- Do you have any recommendations for how to make community resource referrals smoother for patients?

References

- Beauchamp, D.E. Public health as social justice. Inquiry 1976, 13, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, N.; Birn, A.-E. A vision of social justice as the foundation of public health: Commemorating 150 years of the spirit of 1848. Am. J. Public Health 1998, 88, 1603–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lawn, J.E.; Rohde, J.; Rifkin, S.; Were, M.; Paul, V.K.; Chopra, M. Alma-Ata 30 years on: Revolutionary, relevant, and time to revitalise. Lancet 2008, 372, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M.W.; Thompson, T.; McQueen, A.; Garg, R. Addressing Social Needs in Health Care Settings: Evidence, Challenges, and Opportunities for Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2020, 42, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, M.B.; Nguyen, K.H.; Byhoff, E.; Murray, G.F. Screening for Social Risk at Federally Qualified Health Centers: A National Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 62, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraze, T.; Lewis, V.A.; Rodriguez, H.P.; Fisher, E.S. Housing, transportation, and food: How ACOs seek to improve population health by addressing nonmedical needs of patients. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 2109–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, J.W.; Snyder, R.L.; Freeman, S.L.; Carson, S.R.; Ortega, A.N. It’s not just insurance: The Affordable Care Act and population health. Public Health Rep. 2018, 133, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onie, R.D.; Lavizzo-Mourey, R.; Lee, T.H.; Marks, J.S.; Perla, R.J. Integrating social needs into health care: A twenty-year case study of adaptation and diffusion. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzl, J.M.; Maybank, A.; De Maio, F. Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic: The need for a structurally competent health care system. JAMA 2020, 324, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, L.M.; Pantell, M.S.; Solomon, L.S. The National Academy of Medicine Social Care Framework and COVID-19 Care Innovations. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 1411–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, S.T.; Apenteng, B.A.; Kimsey, L.; Peden, A.; Owens, C. COVID-19 and social determinants of health: Medicaid managed care organizations’ experiences with addressing member social needs. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibbins-Domingo, K. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care. JAMA 2019, 322, 1763–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Billioux, A.; Verlander, K.; Anthony, S.; Alley, D. Standardized screening for health-related social needs in clinical settings: The accountable health communities screening tool. NAM Perspect. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, R.C.; Proser, M.; Jester, M.; Li, V.; Hood-Ronick, C.M.; Gurewich, D. Collecting social determinants of health data in the clinical setting: Findings from national PRAPARE implementation. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2020, 31, 1018–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurewich, D.; Garg, A.; Kressin, N.R. Addressing social determinants of health within healthcare delivery systems: A framework to ground and inform health outcomes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 1571–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchis, E.H.; Hessler, D.; Fichtenberg, C.; Adler, N.; Byhoff, E.; Cohen, A.J.; Doran, K.M.; de Cuba, S.E.; Fleegler, E.W.; Lewis, C.C. Part I: A quantitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, S25–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.J.; Hamity, C.; Sharp, A.L.; Jackson, A.H.; Schickedanz, A.B. Patients’ Attitudes and Perceptions Regarding Social Needs Screening and Navigation: Multi-site Survey in a Large Integrated Health System. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzzio, L.; Wellman, R.D.; De Marchis, E.H.; Gottlieb, L.M.; Walsh-Bailey, C.; Jones, S.M.W.; Nau, C.L.; Steiner, J.F.; Banegas, M.P.; Sharp, A.L.; et al. Social Risk Factors and Desire for Assistance Among Patients Receiving Subsidized Health Care Insurance in a US-Based Integrated Delivery System. Ann. Fam. Med. 2022, 20, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser Permanente. Kaiser Permanente Research: Social Needs in America. Available online: https://about.kaiserpermanente.org/content/dam/internet/kp/comms/import/uploads/2019/06/KP-Social-Needs-Survey-Key-Findings.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Garg, A.; Boynton-Jarrett, R.; Dworkin, P.H. Avoiding the unintended consequences of screening for social determinants of health. JAMA 2016, 316, 813–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, E.D.; Morgan, A.U.; Kangovi, S. Screening for unmet social needs: Patient engagement or alienation? NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, L.M.; Lindau, S.T.; Peek, M.E. Why Add “Abolition” to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Social Care Framework? AMA J. Ethics 2022, 24, 170–180. [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer, D.; Diep, A.; Grisham, K. It’s About Trust: Low-Income Parents’ Perspectives on How Pediatricians Can Screen for Social Determinants of Health; Public Agenda: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, D.; Attridge, M.; Fein, J.A. Food for Thought: A Qualitative Evaluation of Caregiver Preferences for Food Insecurity Screening and Resource Referral. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, L.M.; Hoots, B.; Tsang, C.A.; Leroy, Z.; Farris, K.; Jolly, B.; Antall, P.; McCabe, B.; Zelis, C.B.; Tong, I. Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January–March 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temesgen, Z.M.; DeSimone, D.C.; Mahmood, M.; Libertin, C.R.; Palraj, B.R.V.; Berbari, E.F. Health care after the COVID-19 pandemic and the influence of telemedicine. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, S66–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, E.; Roosevelt, G.E.; Vogel, J.A. Screening for health-related social needs in the emergency department: Adaptability and fidelity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 54, 323.e1–323.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Colón, G.D.; Mulaney, B.; Reed, R.E.; Ha, S.K.; Yuan, V.; Liu, X.; Cao, S.; Ambati, V.S.; Hernandez, B.; Cáceres, W. The COVID-19 Pandemic as an Opportunity for Operational Innovation at 2 Student-Run Free Clinics. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 2150132721993631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, R.; Kliot, T.; Weinstein, R.; Onigbanjo, M.; Carter, R. Social needs screening during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Care Health Dev. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. Pragmatism as a paradigm for social research. Qual. Inq. 2014, 20, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, C.; Schafft, K.A. Axiology and anomaly in the practice of mixed methods work: Pragmatism, valuation, and the transformative paradigm. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2015, 9, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemang, B.; Sitter, K.; Dimitropoulos, G. Pragmatism as a paradigm for patient-oriented research. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, L.M.; Cordeiro, M. Three principles of pragmatism for research on organizational processes. Methodol. Innov. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, V.; Walsh, C.A. Pragmatism as a research paradigm and its implications for social work research. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, D.E.; Asomugha, C.N.; Conway, P.H.; Sanghavi, D.M. Accountable health communities—Addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Designing qualitative studies. In Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 3, pp. 209–259. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative interviewing. In Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 3, pp. 339–428. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, A.; Taubman, S.; Wright, B.; Bernstein, M.; Gruber, J.; Newhouse, J.P.; Allen, H.; Baicker, K.; Group, O.H.S. The Oregon health insurance experiment: Evidence from the first year. Q. J. Econ. 2012, 127, 1057–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Maher, A., Ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Venturing Forth! Doing Reflexive Thematic Analysis. In Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines 2012; ACTFL: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2012.

- Indeed Editorial Team. Understanding Your Levels of Fluency and How to Include Them on a Resume. Available online: https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/resumes-cover-letters/levels-of-fluency-resume (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Dedoose, Version 9.0.17. Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data. SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Getting your own house in order: Understanding what makes good reflexive thematic analysis to ensure quality. In Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Maher, A., Ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, C.-N.; Brochier, A.; Pellicer, M.; Garg, A.; Drainoni, M.-L. Implementing social determinants of health screening at community health centers: Clinician and staff perspectives. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2019, 10, 2150132719887260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.; Paul, M.; Massar, R.; Marcello, R.K.; Krauskopf, M. Social Needs Screening and Referral Program at a Large US Public Hospital System, 2017. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, S211–S214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, J.; Mccurley, J.L.; Fung, V.; Levy, D.E.; Clark, C.R.; Thorndike, A.N. Addressing social determinants of health identified by systematic screening in a medicaid accountable care organization: A qualitative study. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 2150132721993651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostelanetz, S.; Pettapiece-Phillips, M.; Weems, J.; Spalding, T.; Roumie, C.; Wilkins, C.H.; Kripalani, S. Health care professionals’ perspectives on universal screening of social determinants of health: A mixed-methods study. Popul. Health Manag. 2021, 25, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.T.; Liaw, W.R.; Kashiri, P.L.; Pecsok, J.; Rozman, J.; Bazemore, A.W.; Krist, A.H. Clinician experiences with screening for social needs in primary care. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2018, 31, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spain, A.K.; Monahan, E.K.; Alvarez, K.; Finno-Velasquez, M. Latinx Family Perspectives on Social Needs Screening and Referral during Well-Child Visits. MCN Am. J. Matern./Child Nurs. 2021, 46, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiles, T.M.; Cernasev, A.; Leibold, C.; Hohmeier, K. Patient Perspectives of Discussing Social Determinants of Health with Community Pharmacists. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broaddus-Shea, E.T.; Fife Duarte, K.; Jantz, K.; Reno, J.; Connelly, L.; Nederveld, A. Implementing health-related social needs screening in western Colorado primary care practices: Qualitative research to inform improved communication with patients. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e3075–e3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.; Khan, S.; Palakshappa, D.; Cahill, R.; Kruger, E.; Poserina, B.G.; Koch, B.; Chilton, M. Successes, challenges, and considerations for integrating referral into food insecurity screening in pediatric settings. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2018, 29, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palakshappa, D.; Doupnik, S.; Vasan, A.; Khan, S.; Seifu, L.; Feudtner, C.; Fiks, A.G. Suburban families’ experience with food insecurity screening in primary care practices. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20170320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byhoff, E.; De Marchis, E.H.; Hessler, D.; Fichtenberg, C.; Adler, N.; Cohen, A.J.; Doran, K.M.; de Cuba, S.E.; Fleegler, E.W.; Gavin, N. Part II: A qualitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, S38–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MA, USA, 2014.

- Oregon Primary Care Association. Principles for Patient-Centered Approaches to Social Needs Screening; Oregon Primary Care Association: Portland, OR, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright, S. The Future of Healing: Shifting from Trauma Informed Care to Healing Centered Engagement; Kinship Carers Victoria: Kensington, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fiori, K.P.; Rehm, C.D.; Sanderson, D.; Braganza, S.; Parsons, A.; Chodon, T.; Whiskey, R.; Bernard, P.; Rinke, M.L. Integrating Social Needs Screening and Community Health Workers in Primary Care: The Community Linkage to Care Program. Clin. Pediatr. 2020, 59, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.K.; Cairns, N.; Sunni, M.; Turnberg, G.L.; Gross, A.C. Addressing food insecurity in a pediatric weight management clinic: A pilot intervention. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2016, 30, e11–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palakshappa, D.; Vasan, A.; Khan, S.; Seifu, L.; Feudtner, C.; Fiks, A.G. Clinicians’ perceptions of screening for food insecurity in suburban pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20170319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marpadga, S.; Fernandez, A.; Leung, J.; Tang, A.; Seligman, H.; Murphy, E.J. Challenges and successes with food resource referrals for food-insecure patients with diabetes. Perm. J. 2019, 23, 18-097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polk, S.; Leifheit, K.M.; Thornton, R.; Solomon, B.S.; DeCamp, L.R. Addressing the Social Needs of Spanish-and English-Speaking Families in Pediatric Primary Care. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manian, N.; Wagner, C.; Placzek, H.; Darby, B.; Kaiser, T.; Rog, D. Relationship between intervention dosage and success of resource connections in a social needs intervention. Public Health 2020, 185, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna, L.R.; Tolou-Shams, M.; Robles-Ramamurthy, B.; Porche, M.V. Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: The need for a trauma-informed social justice response. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paremoer, L.; Nandi, S.; Serag, H.; Baum, F. COVID-19 pandemic and the social determinants of health. BMJ 2021, 372, n129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M.; Garg, R.; Javed, I.; Golla, B.; Wolff, J.; Charles, C. 3.5 million social needs requests during COVID-19: What can we learn from 2-1-1? Health Aff. Forefront 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petchel, S. COVID-19 makes funding for health and social services integration even more crucial. Health Aff. Forefront 2020. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200413.886531 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Kreuter, M.; Garg, R.; Thompson, T.; McQueen, A.; Javed, I.; Golla, B.; Caburnay, C.; Greer, R. Assessing The Capacity Of Local Social Services Agencies To Respond To Referrals From Health Care Providers: An exploration of the capacity of local social service providers to respond to referrals from health care providers to assist low-income patients. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, R.A.; Ziliak, J.P. COVID-19 and the US safety net. Fisc. Stud. 2020, 41, 515–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.W.; Chriqui, J.F.; Andreyeva, T.; Kenney, E.L.; Stage, V.C.; Dev, D.; Lessard, L.; Cotwright, C.J.; Tovar, A. A safety net unraveling: Feeding young children during COVID-19. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, S.; Satterfield, S.J.; Solorzano, G.; Bowen, S.; Hardison-Moody, A.; Williams, L. Disenfranchised: How Lower Income Mothers Navigated the Social Safety Net during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Socius 2021, 7, 23780231211031690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Quinn, J.W.; Hurvitz, P.M.; Hirsch, J.A.; Goldsmith, J.; Neckerman, K.M.; Lovasi, G.S.; Rundle, A.G. Addressing patient’s unmet social needs: Disparities in access to social services in the United States from 1990 to 2014, a national times series study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg-Graham, R.; Edwards, K.; Ely, T.L.; Mochizuki, M.; Varda, D. Exploring the capacity of community-based organisations to absorb health system patient referrals for unmet social needs. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, S.; Batko, S. Five Charts That Explain the Homelessness-Jail Cycle—And How to Break it. Available online: https://www.urban.org/features/five-charts-explain-homelessness-jail-cycle-and-how-break-it (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Velasco, G.; Fedorwicz, M. Applying a Racial Equity Lens to Housing Policy Analysis. Available online: https://housingmatters.urban.org/articles/applying-racial-equity-lens-housing-policy-analysis (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Williams, D.R.; Collins, C. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001, 116, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, K.; Stone, W. The social service divide: Service availability and accessibility in rural versus urban counties and impact on child welfare outcomes. Child Welf. 2008, 87, 101–124. [Google Scholar]

| Demographics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 20 (59%) |

| Male | 14 (41%) |

| “What is your race?” (Select all that apply) * | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (6%) |

| Asian | 1 (3%) |

| Black or African American | 5 (15%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (3%) |

| White | 17 (50%) |

| Other | 7 (21%) |

| No Response | 3 (9%) |

| “Are you Hispanic, Latino/a, or Spanish Origin?” | |

| Yes | 10 (29%) |

| Spanish Language Interview | |

| Yes | 5 (15%) |

| Age | |

| <25 | 7 (21%) |

| 25–34 | 3 (9%) |

| 35–44 | 2 (6%) |

| 45–54 | 9 (26%) |

| 55–64 | 7 (21%) |

| 65–74 | 6 (18%) |

| “What is your highest grade or year of school you completed?” | |

| Never attended school or only kindergarten | 0 (0%) |

| Grades 1–8 (Elementary) | 4 (12%) |

| Grades 9–11 (Some High School) | 4 (12%) |

| Grade 12 or GED (High School) | 11 (32%) |

| College, 1–3 Years (Some College) | 11 (32%) |

| College, 4 Years or more (College Graduate) | 4 (12%) |

| HRSN | |

| Type(s) * | |

| Food | 27 (79%) |

| Housing | 26 (76%) |

| Transportation | 16 (47%) |

| Utilities | 8 (24%) |

| Interpersonal Safety | 3 (9%) |

| Quantity | |

| 1 | 8 (24%) |

| 2 | 10 (29%) |

| 3 | 12 (35%) |

| 4 | 4 (12%) |

| 5 | 0 (0%) |

| AHC Model Intervention & Interview Timing | |

| Clinical Delivery Site | |

| ED | 16 (47%) |

| FQHC | 18 (53%) |

| Months from AHC Model Intervention to Interview | |

| 1 | 2 (6%) |

| 2 | 18 (53%) |

| 3 | 9 (26%) |

| 4 | 2 (6%) |

| 5 | 3 (9%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Steeves-Reece, A.L.; Nicolaidis, C.; Richardson, D.M.; Frangie, M.; Gomez-Arboleda, K.; Barnes, C.; Kang, M.; Goldberg, B.; Lindner, S.R.; Davis, M.M. “It Made Me Feel like Things Are Starting to Change in Society:” A Qualitative Study to Foster Positive Patient Experiences during Phone-Based Social Needs Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912668

Steeves-Reece AL, Nicolaidis C, Richardson DM, Frangie M, Gomez-Arboleda K, Barnes C, Kang M, Goldberg B, Lindner SR, Davis MM. “It Made Me Feel like Things Are Starting to Change in Society:” A Qualitative Study to Foster Positive Patient Experiences during Phone-Based Social Needs Interventions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912668

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteeves-Reece, Anna L., Christina Nicolaidis, Dawn M. Richardson, Melissa Frangie, Katherin Gomez-Arboleda, Chrystal Barnes, Minnie Kang, Bruce Goldberg, Stephan R. Lindner, and Melinda M. Davis. 2022. "“It Made Me Feel like Things Are Starting to Change in Society:” A Qualitative Study to Foster Positive Patient Experiences during Phone-Based Social Needs Interventions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912668

APA StyleSteeves-Reece, A. L., Nicolaidis, C., Richardson, D. M., Frangie, M., Gomez-Arboleda, K., Barnes, C., Kang, M., Goldberg, B., Lindner, S. R., & Davis, M. M. (2022). “It Made Me Feel like Things Are Starting to Change in Society:” A Qualitative Study to Foster Positive Patient Experiences during Phone-Based Social Needs Interventions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912668