Investigating Outcomes of a Family Strengthening Intervention for Resettled Somali Bantu and Bhutanese Refugees: An Explanatory Sequential Mixed Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Resettled Bhutanese and Somali Bantu Communities in New England

1.2. The Family Strengthening Intervention for Refugees (FSI-R)

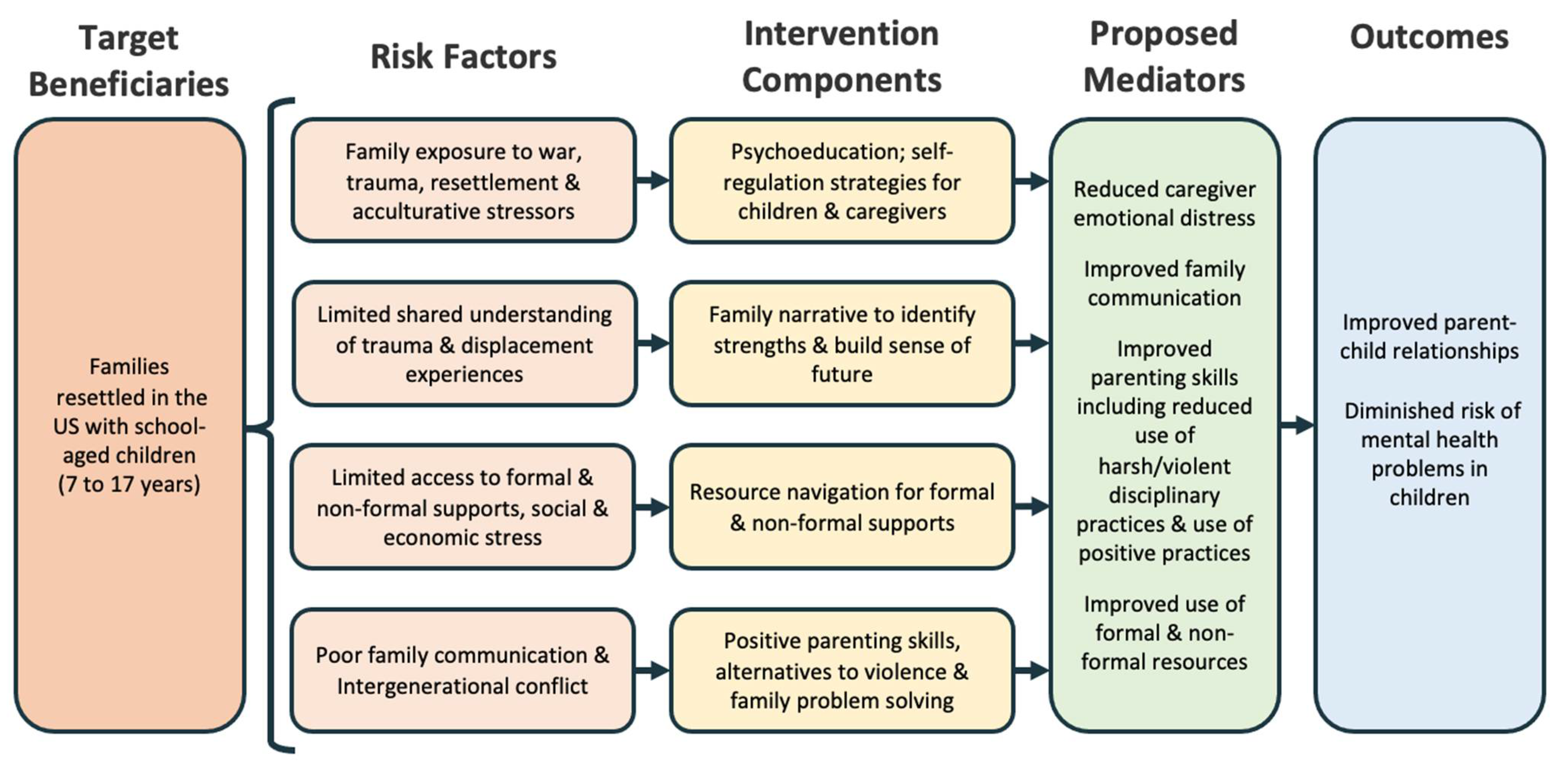

FSI-R Conceptual Model and Theory of Change

1.3. Study Aims

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Quantitative Acceptability and Feasibility Measures

2.1.2. Quantitative Family Outcome Measures

2.1.3. Quantitative Child Outcome Measures

2.1.4. Qualitative Semi-Structured Interviews

2.2. Analysis Strategy

2.2.1. Quantitative Analysis Strategy

2.2.2. Qualitative Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Family Outcomes

“Through the intervention, changes that I’ve seen was like starting from the first module, through to the end I see changes where before they were not like connecting or listening to each other, but now, what they hear from me or learn from me they made a big improvement and learned from me through the modules.”

“During the modules like for example module 4 …parenting strategies, we see disciplining the kids was need[ing] to be, like, taught…before, they didn’t even know anything about that but right now, you know, they have made some new changes about what they have learned through tools from me.”

“With one family... Probably due to their educational status being a bit higher, both caregivers were educated. I got [a] very positive response from them. They said they used to have family discussions in some ways, but they realized they could do it differently and effectively, as discussed in the intervention.”

“It will be different in different families. Some families are in good condition. These families take what I taught and suggest during intervention very positively; therefore, we can see positive impacts on these families, whereas some families do not even care, they are good until the intervention session exists, but after the session is over, they do not follow what was taught or said during the intervention session. I have continuously followed up with those families, but then they respond [that] they are okay! And their lifestyle or [their] relationship does not does not require any changes....For this, I can see I found impact in families 50–50.”

3.2. Child Outcomes

“Before this intervention, I wouldn’t tell anything that happened at school to my parents because I got really worried, cause I used to get bullied. Now, I tell my parents and they help me a lot. And my sisters, they’re there for me too. And I actually tell a lot of stuff to my parents about school, because that makes me more comfortable going to school and learning.”

“It’s been different. Like my child, if I have to say, is of scared type. But he’s not scared these days. He comes to me and says what needs to be done. It’s been good. It’s been going well in family too. I also understand more now, how children need to be loved. I experienced like that and it’s been good for children as well.”

“I know our community have very little knowledge about mental health, and people really doesn’t want to talk about it, and people really doesn’t want to seek mental health help and mental health providers. So I think that piece of mental health information in that module [of the FSI-R] was very helpful, and were having healthy conversation about those things…. In terms of impact, I did saw people started using mental health services.”

3.3. Intervention Acceptability

3.3.1. Overall Satisfaction

3.3.2. Meeting the Participants’ Needs

“[R]esources regarding healthcare, information [about] different types of benefits available for families, educational resources, information on job opportunities; these sorts of information on available resources are handy to us. But, if some families come up with complex problem[s] then, we might not have information on available resources which would help address those issues...”

3.3.3. Interventionists

3.3.4. Content, Exercises, and Information Gained

3.4. Intervention Feasibility

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNHCR. UNHCR Global Trends 2020. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/60b638e37/unhcr-global-trends-2020 (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Frounfelker, R.L.; Tahir, S.; Abdirahman, A.; Betancourt, T.S. Stronger Together: Community Resilience and Somali Bantu Refugees. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2020, 26, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieloch, K.A.; McCullough, M.B.; Marks, A.K. Resilience of Children with Refugee Statuses: A Research Review. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2016, 57, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogic, M.; Njoku, A.; Priebe, S. Long-Term Mental Health of War-Refugees: A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2015, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronstein, I.; Montgomery, P. Psychological Distress in Refugee Children: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kien, C.; Sommer, I.; Faustmann, A.; Gibson, L.; Schneider, M.; Krczal, E.; Jank, R.; Klerings, I.; Szelag, M.; Kerschner, B.; et al. Prevalence of Mental Disorders in Young Refugees and Asylum Seekers in European Countries: A Systematic Review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 1295–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterko, Y.; Jäckle, D.; Friedrich, M.; Holzapfel, L.; Glaesmer, H. Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Depression and Somatisation in Recently Arrived Refugees in Germany: An Epidemiological Study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weine, S.; Muzurovic, N.; Kulauzovic, Y.; Besic, S.; Lezic, A.; Mujagic, A.; Muzurovic, J.; Spahovic, D.; Feetham, S.; Ware, N.; et al. Family Consequences of Refugee Trauma. Fam. Process 2004, 43, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timshel, I.; Montgomery, E.; Dalgaard, N.T. A Systematic Review of Risk and Protective Factors Associated with Family Related Violence in Refugee Families. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 70, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, C.; Measham, T.; Moro, M.-R. Working with Interpreters in Child Mental Health. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2011, 16, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eruyar, S.; Maltby, J.; Vostanis, P. Mental Health Problems of Syrian Refugee Children: The Role of Parental Factors. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Betancourt, T.S.; Abdi, S.; Ito, B.S.; Lilienthal, G.M.; Agalab, N.; Ellis, H. We Left One War and Came to Another: Resource Loss, Acculturative Stress, and Caregiver–Child Relationships in Somali Refugee Families. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2015, 21, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, L.C.; Liamputtong, P.; Walker, R. Burmese Refugee Young Women Navigating Parental Expectations and Resettlement. J. Fam. Stud. 2013, 19, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, F.L.; Mishra, T.; Frounfelker, R.L.; Bhargava, E.; Gautam, B.; Prasai, A.; Betancourt, T.S. ‘Hiding Their Troubles’: A Qualitative Exploration of Suicide in Bhutanese Refugees in the USA. Glob. Ment. Health 2019, 6, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, K.; Bunn, M.; Schuster, R.C.; Boateng, G.O.; Cameli, K.; Johnson-Agbakwu, C.E. A Scoping Review of Social Support Research among Refugees in Resettlement: Implications for Conceptual and Empirical Research. J. Refug. Stud. 2022, 35, 368–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangamma, R. A Phenomenological Study of Family Experiences of Resettled Iraqi Refugees. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2018, 44, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J. Psychotherapy and the Cultural Concept of the Person. Transcult. Psychiatry 2007, 44, 232–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, C.; Ali, S.S.; Roberts, B.; Stewart, R. A Systematic Review of Resilience and Mental Health Outcomes of Conflict-Driven Adult Forced Migrants. Confl. Health 2014, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Betancourt, T.S. Preventive Mental Health Interventions for Refugee Children and Adolescents in High-Income Settings. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weine, S.; Ware, N.; Hakizimana, L.; Tugenberg, T.; Currie, M.; Dahnweih, G.; Wagner, M.; Polutnik, C.; Wulu, J. Fostering Resilience: Protective Agents, Resources, and Mechanisms for Adolescent Refugees’ Psychosocial Well-Being. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 4, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodin, O.; de Jong, J.T.V.M. Family Interventions in Traumatized Immigrants and Refugees: A Systematic Review. Transcult. Psychiatry 2015, 52, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, M.; Zolman, N.; Smith, C.P.; Khanna, D.; Hanneke, R.; Betancourt, T.S.; Weine, S. Family-Based Mental Health Interventions for Refugees across the Migration Continuum: A Systematic Review. SSM-Ment. Health 2022, 2, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities; Institute of Medicine (U.S.); O’Connell, M.E.; Boat, T.F.; Warner, K.E.; National Research Council (U.S.) (Eds.) National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-309-12674-8.

- Cochran, J.; Geltman, P.L.; Ellis, H.; Brown, C.; Anderton, S.; Montour, J.; Vargas, M.; Komatsu, K.; Senseman, C.; Cardozo, B.L.; et al. Suicide and Suicidal Ideation among Bhutanese Refugees—United States, 2009–2012. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. MMWR 2013, 62, 533. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, L. Psychosocial Resilience among Resettled Bhutanese Refugees in the US. Forced Migr. Rev. 2012, 40, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, L.; Sapkota, R.P. “In Our Community, a Friend Is a Psychologist”: An Ethnographic Study of Informal Care in Two Bhutanese Refugee Communities. Transcult. Psychiatry 2017, 54, 400–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.M.; Sharma, B.; Van Ommeren, M.; Regmi, S.; Makaju, R.; Komproe, I.; Shrestha, G.B.; de Jong, J.T.V.M. Impact of Torture on Refugees Displaced Within the Developing World: Symptomatology among Bhutanese Refugees in Nepal. JAMA 1998, 280, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frounfelker, R.L.; Mishra, T.; Carroll, A.; Brennan, R.T.; Gautam, B.; Ali, E.A.A.; Betancourt, T.S. Past Trauma, Resettlement Stress, and Mental Health of Older Bhutanese with a Refugee Life Experience. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, R.F.; Croasmun, A.C.; Pittman, C.; Baird, M.B.; Ross, R. Psychological Distress, Post-Traumatic Stress, and Suicidal Ideation Among Resettled Nepali-Speaking Bhutanese Refugees in the United States: Rates and Predictors. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2022, 33, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonnahme, L.A.; Lankau, E.W.; Ao, T.; Shetty, S.; Cardozo, B.L. Factors Associated with Symptoms of Depression Among Bhutanese Refugees in the United States. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, T.; Shetty, S.; Sivilli, T.; Blanton, C.; Ellis, H.; Geltman, P.L.; Cochran, J.; Taylor, E.; Lankau, E.W.; Lopes Cardozo, B. Suicidal Ideation and Mental Health of Bhutanese Refugees in the United States. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frounfelker, R.L.; Mishra, T.; Dhesi, S.; Gautam, B.; Adhikari, N.; Betancourt, T.S. “We Are All under the Same Roof”: Coping and Meaning-Making among Older Bhutanese with a Refugee Life Experience. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 264, 113311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.H.; Lankau, E.W.; Ao, T.; Benson, M.A.; Miller, A.B.; Shetty, S.; Lopes Cardozo, B.; Geltman, P.L.; Cochran, J. Understanding Bhutanese Refugee Suicide through the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2015, 85, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhoff, J.; Iyiewuare, P.; Mulder, L.A.; Rohan, K.J. A Qualitative Study of Perceptions of Risk and Protective Factors for Suicide among Bhutanese Refugees. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2021, 12, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagaman, A.K.; Sivilli, T.I.; Ao, T.; Blanton, C.; Ellis, H.; Lopes Cardozo, B.; Shetty, S. An Investigation into Suicides among Bhutanese Refugees Resettled in the United States between 2008 and 2011. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDowell, H.; Pyakurel, S.; Acharya, J.; Morrison-Beedy, D.; Kue, J. Perceptions Toward Mental Illness and Seeking Psychological Help among Bhutanese Refugees Resettled in the U.S. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 41, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lehman, D.; Eno, O. The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture; Cultural Orientation Resource Center at the Center for Applied Linguistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Besteman, C.L. Making Refuge: Somali Bantu Refugees and Lewiston, Maine; Global Insecurities; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-8223-6027-8. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, T.S.; Frounfelker, R.; Mishra, T.; Hussein, A.; Falzarano, R. Addressing Health Disparities in the Mental Health of Refugee Children and Adolescents Through Community-Based Participatory Research: A Study in 2 Communities. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, S475–S482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.H.; MacDonald, H.Z.; Lincoln, A.K.; Cabral, H.J. Mental Health of Somali Adolescent Refugees: The Role of Trauma, Stress, and Perceived Discrimination. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birman, D.; Tran, N. The Academic Engagement of Newly Arriving Somali Bantu Students in a U.S. Elementary School; Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Michlig, G.J.; Johnson-Agbakwu, C.; Surkan, P.J. “Whatever You Hide, Also Hides You”: A Discourse Analysis on Mental Health and Service Use in an American Community of Somalis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettmann, J.E.; Penney, D.; Clarkson Freeman, P.; Lecy, N. Somali Refugees’ Perceptions of Mental Illness. Soc. Work Health Care 2015, 54, 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.H.; Lincoln, A.K.; Charney, M.E.; Ford-Paz, R.; Benson, M.; Strunin, L. Mental Health Service Utilization of Somali Adolescents: Religion, Community, and School as Gateways to Healing. Transcult. Psychiatry 2010, 47, 789–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.B.; Duran, B. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities. Health Promot. Pract. 2006, 7, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, T.S.; Frounfelker, R.L.; Berent, J.M.; Gautam, B.; Abdi, S.; Abdi, A.; Haji, Z.; Maalim, A.; Mishra, T. Addressing Mental Health Disparities in Refugee Children through Family and Community-Based Prevention. In Humanitarianism and Mass Migration: Confronting the World Crisis; Suárez-Orozco, M.M., Ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-520-96962-9. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, T.S.; Berent, J.M.; Freeman, J.; Frounfelker, R.L.; Brennan, R.T.; Abdi, S.; Maalim, A.; Abdi, A.; Mishra, T.; Gautam, B.; et al. Family-Based Mental Health Promotion for Somali Bantu and Bhutanese Refugees: Feasibility and Acceptability Trial. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-8261-4192-7. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente-Bosco, K.; Neville, S.E.; Berent, J.M.; Farrar, J.; Mishra, T.; Abdi, A.; Beardslee, W.R.; Creswell, J.W.; Betancourt, T.S. Understanding Mechanisms of Change in a Family-Based Preventive Mental Health Intervention for Refugees by Refugees in New England. Transcult. Psychiatry 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4833-4437-9. [Google Scholar]

- Essau, C.A.; Sasagawa, S.; Frick, P.J. Psychometric Properties of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2006, 15, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.-W.; Lee, P.A.; Tsai, J.L. Psychometric Properties of The Intergenerational Congruence in Immigrant Families: Child Scale in Chinese Americans. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2004, 35, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos, R.S.; Rodriguez, N.; Steinberg, A.S.; Frederick, C. The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM IV (Revision 1); UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Program: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile; University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software, Release 15; Stata Corp: College Station, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grounded Theory in Practice; Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. (Eds.) Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-7619-0747-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-8039-5939-2. [Google Scholar]

- MAXQDA 2018; VERBI Software: Berlin, Germany, 2017.

- Poudel-Tandukar, K.; Jacelon, C.S.; Chandler, G.E.; Gautam, B.; Palmer, P.H. Sociocultural Perceptions and Enablers to Seeking Mental Health Support Among Bhutanese Refugees in Western Massachusetts. Int. Q. Community Health. Educ. 2019, 39, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frounfelker, R.L.; Assefa, M.T.; Smith, E.; Hussein, A.; Betancourt, T.S. “We Would Never Forget Who We Are”: Resettlement, Cultural Negotiation, and Family Relationships among Somali Bantu Refugees. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 1387–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Individuals, n | Female, n (%) | Age, M (Range) | Years in U.S., M (Range) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative study participants (n = 257) | Somali Bantu children | 103 | 61 (59%) | 14.6 (8–22) | 8 (8–15) |

| Somali Bantu caregivers | 43 | 34 (79%) | 41.8 (28–70) | 13.3 (12–22) | |

| Bhutanese children | 49 | 26 (53%) | 14.4 (8–18) | 4.0 (1–8) | |

| Bhutanese caregivers | 62 | 32 (52%) | 41 (27–66) | 4.3 (1–10) | |

| Qualitative sub-study participants (intervention families only) (n = 36) | Somali Bantu children | 8 | 4 (50%) | 14.5 (11–17) | 12.7 (11–15) |

| Somali Bantu caregivers | 10 | 9 (90%) | 40.1 (32–52) | 13.3 (12–15) | |

| Bhutanese children | 9 | 3 (33%) | 15.7 (12–18) | 4.7 (1–8) | |

| Bhutanese caregivers | 9 | 4 (44%) | 46.1 (34–60) | 4.6 (1–7) |

| Quantitative Results | Qualitative Results | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | SB (β) | B (β) | ||

| Poor monitoring † | 0.01 | −0.01 | “We do practice the skills or information we learned in the intervention, [like] family meeting, spending more playtime with the kids, meeting with school teachers regularly.”—Somali Bantu mother, age 37 “We are interacting more with each other, keeping [in the] loop with school, and also continue doing family talking time together. I started calling school to know about the informations.”—Bhutanese mother, age 40 “Some families…take what I taught …very positively; therefore, we can see positive impacts on these families, whereas some families do not even care…after the session is over they do not follow what was taught or said during the intervention session.…For this, I can see I found impact in families 50–50.”—Bhutanese interventionist “Probably due to their educational status being a bit higher…I got [a] very positive response from them…they realized they could do [family discussions] differently and effectively, as discussed in the intervention.”—Bhutanese interventionist | Families reported meaningful impacts in communication and spending time together. These were important changes according to the participants and may also have contributed to the findings observed on intergenerational congruence as reported by parents and children. Interventionists perceived differential impacts based on family education level and literacy. Such differential outcomes could have muted overall quantitative results in a small-sample pilot. |

| Parental involvement † | −5.41 * | −0.07 | ||

| Positive parenting † | 0.06 | 0.11 | ||

| Intergenerational congruence † | −0.06 | 0.04 | ||

| Intergenerational congruence ‡ | −0.46 | −0.04 | ||

| Quantitative Results | Qualitative Results | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | SB (β) | B (β) | ||

| Depression/anxiety † | 0.18 | −0.07 | “Our community ha[s] very little knowledge about mental health and people really doesn’t want to talk about it and people really doesn’t want to seek mental health help…so I think that piece of mental health information in that module was very helpful, and were having healthy conversation about those things.… In terms of impact, I did saw people started using mental health services.” —Bhutanese interventionist “My child…is of scared type. But he’s not scared these days. He comes to me and says what needs to be done.”—Bhutanese mother, age 44 | Mental health was a very stigmatized topic for families, many of whom were learning about the importance of mental health promotion and how to access mental health services for the first time. Bhutanese children had reduced adult-reported depression and anxiety, and many Bhutanese families spoke of their children’s reduced anxiety in interviews. Somali families, on the other hand, did not comment on child mental health. The intervention’s sample size was too small to detect any impacts on child mental health across measures. |

| Depression/anxiety ‡ | −0.06 | −9.20 * | ||

| Functional impairment † | −0.02 | −0.15 | ||

| Functional impairment ‡ | −0.01 | 0.13 | ||

| Conduct problems † | 0.17 | −0.34 | ||

| Conduct problems ‡ | 1.48 *** | −0.92 * | ||

| Suicidal ideation † | 0.55 * | −0.79 | ||

| Trauma symptoms † | −0.30 | −0.28 | ||

| Quantitative Results | Qualitative Results | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | SB (%) | B (%) | ||

| Satisfied in general | 76.9% | 85.7% | “[You should] add more families [to the intervention] and more times.”—Somali Bantu mother, age 47 “Others also need this [intervention].” —Bhutanese boy, age 16 “Very satisfied. It was fun, especially when we all together discussing about our family.”—Somali Bantu mother, age 37 “When you first come…my thought was there is a program starting in the community for all family to participate but it was just one-on-one meeting and family meeting asking questions. I didn’t like it. People need actual help. Start a family program…like you remember the money saving we did before? Like that.”—Somali Bantu mother, age 42 “When we explained [to] them our boundaries, what we could do and what we could not do for them, they felt a bit uncomfortable.”—Bhutanese interventionist “Resources regarding healthcare,… education,…job opportunities; these sorts of…resources are handy [available] to us. But, if some families come up with complex problem then, we might not have information on available resources…such as violence, sexual assault, children out of school, mental health.”—Bhutanese interventionist | Families expressed general satisfaction with the intervention and the intervention appeared to be acceptable overall. Families have many other needs, e.g., financial, that were not met by a talk-based intervention alone. Although interventionists were able to connect participants with community resources, interventionists sometimes felt they lacked the information they needed for complex problems, and some families needed more than referrals (such as intensive case management); interventionists sometimes felt the help needed exceeded their ability to deliver. |

| Willing to participate again | 100% | 64.3% | ||

| Would recommend to a neighbor/friend | 100% | 85.7% | ||

| Continues to practice skills/knowledge from FSI-R | 61.5% | 100% | ||

| FSI-R met the participants’ needs | 53.8% | 78.6% | ||

| Quantitative Results | Qualitative Results | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | SB (%) | B (%) | ||

| Satisfied with the interventionist | 100% | 100% | “Still I get phone calls from some of the families, [laughs] they miss us so much.”—Bhutanese interventionist “It was more comfortable working with [the interventionist] because I knew him [before the intervention].”—Bhutanese boy, age 18 | Families were very happy with their interventionists across the board. Hiring fellow community members as interventionists was an effective strategy for intervention acceptability. |

| Satisfied with content | 76.9% | 92.9% | “We are satisfied with the intervention because we learned a lot that we didn’t know, like parenting strategies, education system in the U.S., family meeting.”—Somali Bantu mother, age 37 “We have learned many things from this program. Like…things we should do to help kids in their school…that we should talk to their teachers…and how they are doing in school…we learned these things that we didn’t really know before.” —Bhutanese father, age 65 “Too much unnecessary information. Who doesn’t know parenting? Once you get a child, your mind and body automatically start thinking like a parent.”—Somali Bantu mother, age 42 | Respondents generally reported satisfaction with the skills and knowledge gained, especially around the U.S. school system. Still, there were some barriers to acceptability, especially among Somali Bantu caregivers. In particular, non-violent discipline practices, though important to introduce, may not be fully embraced in a ten-session intervention. |

| Satisfied with exercises | 76.9% | 100% | ||

| Satisfied with information gained | 100% | 100% | ||

| Quantitative Results | Qualitative Results | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | SB (%) | B (%) | ||

| Satisfied with length | 76.9% | 92.9% | “Most of the time there was, ‘Okay Mrs./Mr. So-and-So is not here today, so you want to come back another time?’ You see one time a father is not home, but the mother says…, ‘Okay today my husband is not here and my son is not there as well, so you want to just reschedule again’… If the father is missing or the mother is missing then the intervention wasn’t fully delivered the way it is supposed to be.”—Somali Bantu interventionist | It was difficult to bring all the members of a family together in one place for sessions due to their busy schedules, especially for Somali Bantu families, which tended to be larger. |

| Satisfied with how family was able to get through each session | 76.9% | 100% | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neville, S.E.; DiClemente-Bosco, K.; Chamlagai, L.K.; Bunn, M.; Freeman, J.; Berent, J.M.; Gautam, B.; Abdi, A.; Betancourt, T.S. Investigating Outcomes of a Family Strengthening Intervention for Resettled Somali Bantu and Bhutanese Refugees: An Explanatory Sequential Mixed Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912415

Neville SE, DiClemente-Bosco K, Chamlagai LK, Bunn M, Freeman J, Berent JM, Gautam B, Abdi A, Betancourt TS. Investigating Outcomes of a Family Strengthening Intervention for Resettled Somali Bantu and Bhutanese Refugees: An Explanatory Sequential Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912415

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeville, Sarah Elizabeth, Kira DiClemente-Bosco, Lila K. Chamlagai, Mary Bunn, Jordan Freeman, Jenna M. Berent, Bhuwan Gautam, Abdirahman Abdi, and Theresa S. Betancourt. 2022. "Investigating Outcomes of a Family Strengthening Intervention for Resettled Somali Bantu and Bhutanese Refugees: An Explanatory Sequential Mixed Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912415

APA StyleNeville, S. E., DiClemente-Bosco, K., Chamlagai, L. K., Bunn, M., Freeman, J., Berent, J. M., Gautam, B., Abdi, A., & Betancourt, T. S. (2022). Investigating Outcomes of a Family Strengthening Intervention for Resettled Somali Bantu and Bhutanese Refugees: An Explanatory Sequential Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912415