Ongoing Bidirectional Feedback between Planning and Assessment in Educational Contexts: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. An Emergent and Flexible Perspective of Planning

3. Assessment: From a Formality to a Relevant Educational Tool

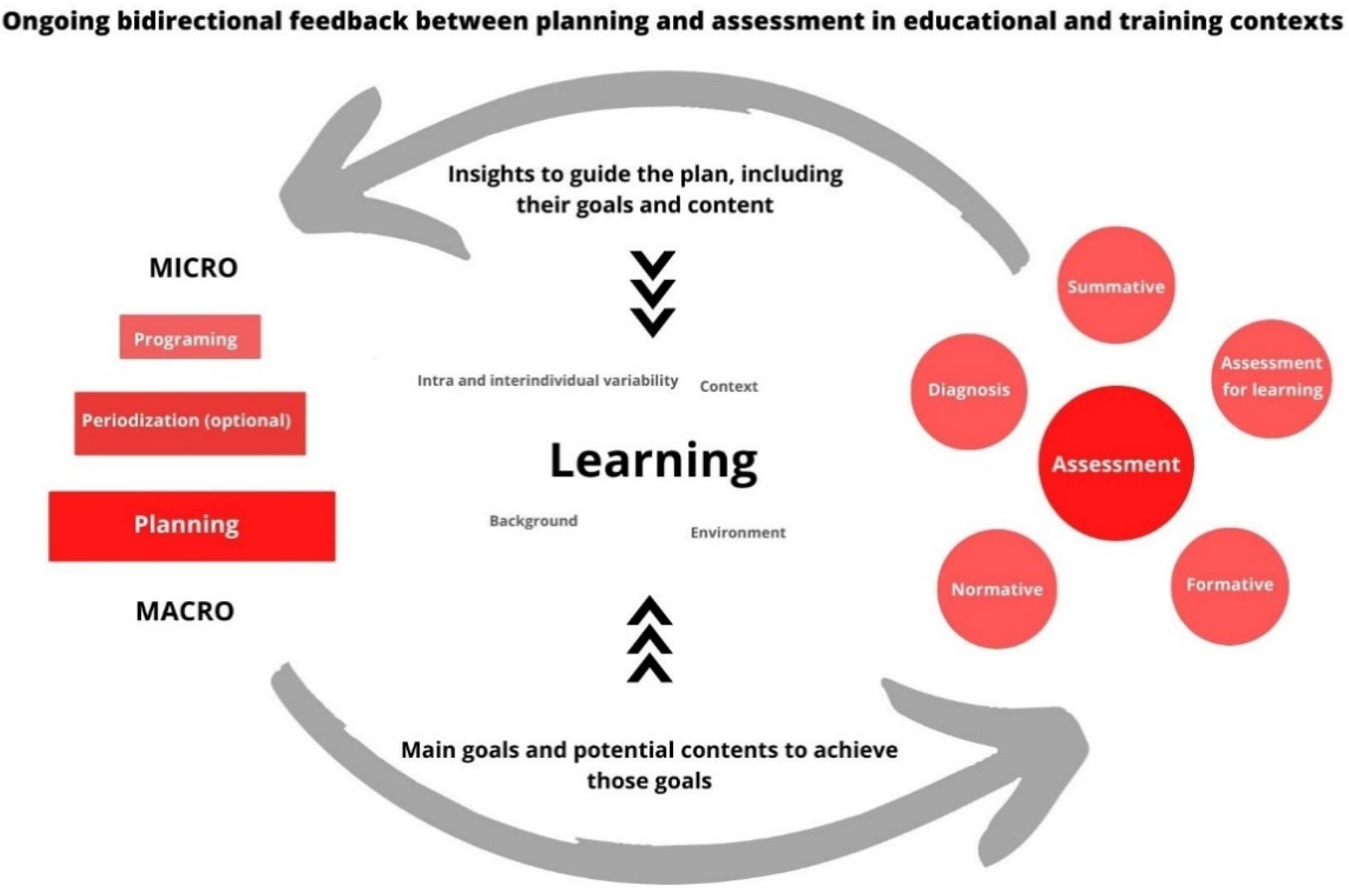

4. Ongoing Bidirectional Feedback between Assessment and Planning

5. Practical Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Michael, R.D.; Webster, C.; Patterson, D.; Laguna, P.; Sherman, C. Standards-based assessment, grading, and professional development of California middle school physical education teachers. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2016, 35, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, D. Equality, equity and inclusion in physical education and school sport. In The Sociology of Sport and Physical Education: An Introductory Reader; RoutledgeFalmer: London, UK, 2002; pp. 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, J.; Ramos, A.; Coutinho, P.; Mesquita, I.; Clemente, F.M.; Farias, C. Creative learning activities: Thinking and playing ‘outside the box’. In Sport Learner-Oriented Development and Assessment of Team Sports and Games in Children and Youth Sport: Teaching Creative, Meaningful, and Empowering Learning Activities; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Pérez, S.; Fernandez-Rio, J.; Iglesias Gallego, D. Effects of an 8-week cooperative learning intervention on physical education students’ task and self-approach goals, and emotional intelligence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beni, S.; Fletcher, T.; Ní Chróinín, D. Meaningful experiences in physical education and youth sport: A review of the literature. Quest 2017, 69, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretchmar, R.S. What to do with meaning? A research conundrum for the 21st century. Quest 2007, 59, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, I.; Ramos, A.; Coutinho, P.; Afonso, J. Appropriateness-based learning activities: Reaching out to every learner. In Learner-Oriented Teaching and Assessment in Youth Sport; Mesquita, C.F.I., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, I.; Afonso, J.; Coutinho, P.; Ramos, A.; Farias, C. Sport learner-oriented development and assessment of team sports and games in children and youth sport: Teaching creative, meaningful, and empowering learning activities. In Learner-Oriented Teaching and Assessment in Youth Sport; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.L.; Armour, K.M.; Potrac, P. Constructing expert knowledge: A case study of a top-level professional soccer coach. Sport Educ. Soc. 2003, 8, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunanan, A.J.; DeWeese, B.H.; Wagle, J.P.; Carroll, K.M.; Sausaman, R.; Hornsby, W.G.; Haff, G.G.; Triplett, N.T.; Pierce, K.C.; Stone, M.H. The general adaptation syndrome: A foundation for the concept of periodization. Sport. Med. 2018, 48, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, J.; Mesquita, I. How do coaches from individual sports engage the interplay between longand short-term planning? RPCD 2018, 18, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, W.; Kemmis, S. Becoming Critical: Education Knowledge and Action Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, J.; Clemente, F.M.; Ribeiro, J.; Ferreira, M.; Fernandes, R.J. Towards a de facto nonlinear periodization: Extending nonlinearity from programming to periodizing. Sports 2020, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushion, C.J.; Armour, K.M.; Jones, R.L. Coach education and continuing professional development: Experience and learning to coach. Quest 2003, 55, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feu, S.; García-Rubio, J.; Gamero, M.d.G.; Ibáñez, S.J. Task planning for sports learning by physical education teachers in the pre-service phase. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bompa, T.O.; Buzzichelli, C. Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, 6th ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi, K. ‘The best guess for the future?’ Teachers’ adaptation to open and flexible learning environments in Finland. Educ. Inq. 2021, 12, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booysen, R.M. The Perspectives of Secondary School Teachers Regarding the Flexible Implementation of the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement; North-West University: Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, M.; Jukic, I. Optimal vs. Robust: Applications to Planning Strategies. Insights from a Simulation Study; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, P.; Afonso, J.; Ramos, A.; Bessa, C.; Farias, C.; Mesquita, I. Harmonizing the learning-assessment cycle. In Learner-Oriented Teaching and Assessment in Youth Sport; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- López-Pastor, V.M.; Kirk, D.; Lorente-Catalán, E.; MacPhail, A.; Macdonald, D. Alternative assessment in physical education: A review of international literature. Sport Educ. Soc. 2013, 18, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.; Stylianides, G.; Djaoui, L.; Dellal, A.; Chamari, K. Session-RPE method for training load monitoring: Validity, ecological usefulness, and influencing factors. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. Assessment for learning. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 2005, 1, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, R. Assessment as learning: Examining a cycle of teaching, learning, and assessment of writing in the portfolio-based classroom. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 1900–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, I.; Afonso, J.; Coutinho, P.; Ramos, A.; Farias, C. Implementing learner-oriented assessment strategies. In Learner-Oriented Teaching and Assessment in Youth Sport; Mesquita, C.F.I., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso, J.; Farias, C.; Ramos, A.; Coutinho, P.; Mesquita, I. Empowering self-assessment, peer-assessment, and sport learning through technology. In Sport Learner-Oriented Development and Assessment of Team Sports and Games in Children and Youth Sport: Teaching Creative, Meaningful, and Empowering Learning Activities; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka, R.; Vasenina, E.; Loenneke, J.; Buckner, S.L. Periodization: Variation in the definition and discrepancies in study design. Sport. Med. 2021, 51, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P. Assessment for learning in physical education. In The Handbook of Physical Education; Macdonald, D.K.D., OSullivan, M., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 312–325. [Google Scholar]

- Bettany-Saltikov, J. Learning how to undertake a systematic review: Part 2. Nurs. Stand. 2010, 24, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furley, P.; Goldschmied, N. Systematic vs. narrative reviews in sport and exercise psychology: Is either approach superior to the other? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 685082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med. Writ. 2015, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pae, C.U. Why systematic review rather than narrative review? Psychiatry Investig. 2015, 12, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, A.; Cherney, A.; White, R.; Clancey, G. Crime Prevention: Principles, Perspectives and Practices; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Suchomel, T.J.; Nimphius, S.; Bellon, C.R.; Stone, M.H. The importance of muscular strength: Training considerations. Sport. Med. 2018, 48, 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.E.; Bradley-Popovich, G.; Haff, G. Nonlinear versus linear periodization models. Strength Cond. J. 2001, 23, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceiçao, F.A.V.; Affonso, H. Programing and periodization for individual sports. In Resistance Training Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.H.; Hornsby, W.G.; Haff, G.G.; Fry, A.C.; Suarez, D.G.; Liu, J.; Gonzalez-Rave, J.M.; Pierce, K.C. Periodization and block periodization in sports: Emphasis on strength-power training—A provocative and challenging narrative. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 2351–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haff, G. Periodization and Power Integration; Kinetics, H., Ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2017; pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Picariello, S. Purposeful planning in physical education. Phys. Educ. 1957, 14, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Kietlinska, Z. The pedagogy of higher education–research problems. High. Educ. Q. 1947, 1, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, M. Instructional Models in Physical Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Loturco, I.; Nakamura, F.Y. Training periodisation: An obsolete methodology. Aspetar Sport. Med. J. 2016, 5, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, W.A.; McNeal, J.R. Predicting athlete preparation and performance: A theoretical perspective. J. Sport Behav. 2000, 23, 289. [Google Scholar]

- Raviv, L.; Lupyan, G.; Green, S.C. How variability shapes learning and generalization. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2022, 26, 462–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, K.M.; Liu, Y.-T.; Mayer-Kress, G. Time scales in motor learning and development. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 108, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K.; Cole, W.G.; Golenia, L.; Adolph, K.E. The cost of simplifying complex developmental phenomena: A new perspective on learning to walk. Dev. Sci. 2018, 21, e12615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, A.; Coutinho, P.; Ribeiro, J.; Fernandes, O.; Davids, K.; Mesquita, I. How can team synchronisation tendencies be developed combining Constraint-led and Step-game approaches? An action-research study implemented over a competitive volleyball season. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2022, 22, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pass, J.; Nelson, L.; Doncaster, G. Real world complexities of periodization in a youth soccer academy: An explanatory sequential mixed methods approach. J. Sport. Sci. 2022, 40, 1290–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, J. Periodization theory: Confronting an inconvenient truth. Sport. Med. 2018, 48, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issurin, V.B. New horizons for the methodology and physiology of training periodization. Sport. Med. 2010, 40, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issurin, V.B. Biological background of block periodized endurance training: A review. Sport. Med. 2019, 49, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matveyev, L. Fundamentals of Sports Training; Progress Publishers: Moscow, Russia, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Abt, J.P.; Oliver, J.M.; Nagai, T.; Sell, T.C.; Lovalekar, M.T.; Beals, K.; Wood, D.E.; Lephart, S.M. Block-periodized training improves physiological and tactically relevant performance in Naval Special Warfare Operators. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Fernandes, R.J.; de Jesus, K.; Pelarigo, J.G.; Arroyo-Toledo, J.J.; Vilas-Boas, J.P. Do traditional and reverse swimming training periodizations lead to similar aerobic performance improvements? J. Sport. Med. Phys. Fit. 2018, 58, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhea, M.R.; Ball, S.D.; Phillips, W.T.; Burkett, L.N. A comparison of linear and daily undulating periodized programs with equated volume and intensity for strength. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2002, 16, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ravé, J.M.; Hermosilla, F.; González-Mohíno, F.; Casado, A.; Pyne, D.B. Training intensity distribution, training volume, and periodization models in elite swimmers: A systematic review. Int. J. Sport. Physiol. Perform. 2021, 16, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, J. Periodization paradigms in the 21st century: Evidence-led or tradition-driven? Int. J. Sport. Physiol. Perform. 2012, 7, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, J.; Rocha, T.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Clemente, F.M.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B. A systematic review of meta-analyses comparing periodized and non-periodized exercise programs: Why we should go back to original research. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 01023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, D.; Hristovski, R.; Seifert, L.; Carvalho, J.; Davids, K. Ecological cognition: Expert decision-making behaviour in sport. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickles, D.; Hawe, P.; Shiell, A. A simple guide to chaos and complexity. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, N.; Decker, L.M. Human movement variability, nonlinear dynamics, and pathology: Is there a connection? Hum. Mov. Sci. 2011, 30, 869–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawale, A.K.; Smith, M.A.; Olveczky, B.P. The role of variability in motor learning. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 40, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelen, E.; Smith, L.B. A Dynamic Systems Approach to the Development of Cognition and Action; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balague, N.; Torrents, C.; Hristovski, R.; Davids, K.; Araújo, D. Overview of complex systems in sport. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 2013, 26, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, K.; Hristovski, R.; Araújo, D.; Serre, N.B.; Button, C.; Passos, P. Complex Systems in Sport; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Simão, R.; Spineti, J.; de Salles, B.F.; Matta, T.; Fernandes, L.; Fleck, S.J.; Rhea, M.R.; Strom-Olsen, H.E. Comparison between nonlinear and linear periodized resistance training: Hypertrophic and strength effects. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, J.Y.; Davids, K.; Button, C.; Renshaw, I. Nonlinear Pedagogy in Skill Acquisition: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schollhorn, W.; Hegen, P.; Davids, K. The nonlinear nature of learning—A differential learning approach. Open Sport. Sci. J. 2012, 5, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raw, R.K.; Wilkie, R.M.; Allen, R.J.; Warburton, M.; Leonetti, M.; Williams, J.H.; Mon-Williams, M. Skill acquisition as a function of age, hand and task difficulty: Interactions between cognition and action. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.; Davids, K.; Silva, P.; Coutinho, P.; Barreira, D.; Garganta, J. Talent development in sport requires athlete enrichment: Contemporary insights from a nonlinear pedagogy and the athletic skills model. Sport. Med. 2021, 51, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahedero, M.P.; Calderón, A.; Hastie, P.; Arias-Estero, J.L. Grouping students by skill level in mini-volleyball: Effect on game performance and knowledge in sport education. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2021, 128, 1851–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middaugh, M.F. Planning and Assessment in Higher Education: Demonstrating Institutional Effectiveness; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banta, T.W.; Pike, G.R.; Hansen, M.J. The use of engagement data in accreditation, planning, and assessment. New Dir. Inst. Res. 2009, 2009, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Práxedes, A.; Del Villar Álvarez, F.; Moreno, A.; Gil-Arias, A.; Davids, K. Effects of a nonlinear pedagogy intervention programme on the emergent tactical behaviours of youth footballers. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 24, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altavilla, G. Monitoring training to adequate the teaching method in training: An interpretative concepts. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2019, 19, 1763–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joughin, G. Assessment, learning and judgement in higher education: A critical review. In Assessment, Learning and Judgement in Higher Education; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taras, M. Using assessment for learning and learning from assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2002, 27, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.E.; Kelly, L.; Melograno, V. Developing the Physical Education Curriculum: An Achievement-Based Approach; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Leirhaug, P.E.; MacPhail, A.; Annerstedt, C. ‘The grade alone provides no learning’: Investigating assessment literacy among Norwegian physical education teachers. Asia-Pac. J. Health Sport Phys. Educ. 2016, 7, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.A.; Oslin, J.L.; Griffin, L.L. Sport Foundations for Elementary Physical Education: A Tactical Games Approach; ERIC: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, S.; Kempton, T.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Coutts, A.J. Training monitoring in professional Australian football: Theoretical basis and recommendations for coaches and scientists. Sci. Med. Footb. 2020, 4, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C.T.; Rothwell, M.; Rudd, J.; Robertson, S.; Davids, K. Representative co-design: Utilising a source of experiential knowledge for athlete development and performance preparation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 52, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, L.; Farrow, D.; Reid, M.; Buszard, T.; Pinder, R. Helping coaches apply the principles of representative learning design: Validation of a tennis specific practice assessment tool. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, D.T.; Heroman, C.; Charles, J.; Maiorca, J. Beyond outcomes: How ongoing assessment supports children’s learning and leads to meaningful curriculum. YC Young Child. 2004, 59, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Dixson, D.D.; Worrell, F.C. Formative and summative assessment in the classroom. Theory Into Pract. 2016, 55, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkamp, K.; van der Kleij, F.M.; Heitink, M.C.; Kippers, W.B.; Veldkamp, B.P. Formative assessment: A systematic review of critical teacher prerequisites for classroom practice. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 103, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, L.S.; Lund, J. Assessment for learning in physical education: The what, why and how. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2018, 89, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I. Assessment is for learning: Formative assessment and positive learning interactions. Fla. J. Educ. Adm. Policy 2008, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cobley, S.; Till, K. Longitudinal studies of athlete development: Their importance, methods and future considerations. In Routledge Handbook of Talent Identification and Development in Sport; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 250–268. [Google Scholar]

- Till, K.; Cobley, S.; O’Hara, J.; Chapman, C.; Cooke, C. An individualized longitudinal approach to monitoring the dynamics of growth and fitness development in adolescent athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacPhail, A.; Halbert, J. ‘We had to do intelligent thinking during recent PE’: Students’ and teachers’ experiences of assessment for learning in post-primary physical education. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2010, 17, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkinson, G.R.; Carver, K.D.; Atkinson, F.; Daniell, N.D.; Lewis, L.K.; Fitzgerald, J.S.; Lang, J.J.; Ortega, F.B. European normative values for physical fitness in children and adolescents aged 9–17 years: Results from 2 779 165 Eurofit performances representing 30 countries. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2018, 52, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J. Test–retest reliability of the EUROFIT test battery: A review. Sport Sci. Health 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.; Penney, D. Assessment in Physical Education: A Sociocultural Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgrò, F.; Coppola, R.; Schembri, R.; Lipoma, M. The effects of a tactical games model unit on students’ volleyball performances in elementary school. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2021, 27, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, O.; Brunsdon, J.J. Changing the score: Alternative assessment strategies and tools for sport in middle school physical education. Strategies 2022, 35, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacharn, P.; Bay, D.; Felton, S. The impact of a flexible assessment system on students’ motivation, performance and attitude. Account. Educ. 2013, 22, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquero-Ruiz, C.; Kirk, D.; Arias-Estero, J.L. Design and validation of the Tactical Assessment Instrument in football (TAIS). Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2021, 93, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez, S.J.; Martinez-Fernández, S.; Gonzalez-Espinosa, S.; García-Rubio, J.; Feu, S. Designing and validating a basketball learning and performance assessment instrument (BALPAI). Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grehaigne, J.-F.; Godbout, P.; Bouthier, D. Performance assessment in team sports. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 1997, 16, 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslin, J.L.; Mitchell, S.A.; Griffin, L.L. The game performance assessment instrument (GPAI): Development and preliminary validation. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 1998, 17, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.; Mesquita, I.; Hastie, P.; Pereira, C. Students’ game performance improvements during a hybrid sport education–step-game-approach volleyball unit. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2016, 22, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.C.R.; Castro, H.d.O.; Freire, A.B.; Faria, B.C.; Mitre, G.P.; Fonseca, F.d.S.; Lima, C.O.V.; Costa, G.D.C.T. Analysis of the small-sided games in volleyball: An ecological approach. Rev. Bras. Cineantropometria Desempenho Hum. 2020, 22, e70184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boud, D. Sustainable assessment: Rethinking assessment for the learning society. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2000, 22, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, G.T. Integrative assessment: Reframing assessment practice for current and future learning. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupert, E.; Gupta, L.; Holder, T.; Jobson, S.A. Athlete monitoring practices in elite sport in the United Kingdom. J. Sport. Sci. 2022, 40, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, N.A.; Goncalves, B.; Coutinho, D.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Travassos, B. How playing area dimension and number of players constrain football performance during unbalanced ball possession games. Int. J. Sport. Sci. Coach. 2021, 16, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, I.; Garganta, J.; Greco, P.; Mesquita, I.; Maia, J. System of tactical assessment in Soccer (FUT-SAT): Development and preliminary validation. System 2011, 7, 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pinder, R.A.; Davids, K.; Renshaw, I.; Araújo, D. Representative learning design and functionality of research and practice in sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2011, 33, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgado, H.; Duarte, R.; Fernandes, O.; Sampaio, J. Competing with lower level opponents decreases intra-team movement synchronization and time-motion demands during pre-season soccer matches. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sanchez, J.; Botella, J.; Felipe Hernandez, J.L.; León, M.; Paredes-Hernández, V.; Colino, E.; Gallardo, L.; Garcia-Unanue, J. Heart rate variability and physical demands of in-season youth elite soccer players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, T. Applied and theoretical perspectives of performance analysis in sport: Scientific issues and challenges. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2009, 9, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.B. Sweating Rate and Sweat Sodium Concentration in Athletes: A Review of Methodology and Intra/Interindividual Variability. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, E.; García-Calvo, T.; Resta, R.; Blanco, H.; López del Campo, R.; Díaz García, J.; Pulido, J.J. A comparison of a GPS device and a multi-camera video technology during official soccer matches: Agreement between systems. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, N.; Harbourne, R.T.; Cavanaugh, J.T. Optimal movement variability: A new theoretical perspective for neurologic physical therapy. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2006, 30, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Isanto, T.; D’Elia, F.; Raiola, G.; Altavilla, G. Assessment of sport performance: Theoretical aspects and practical indications. Sport Mont 2019, 17, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.F.; Silva, A.; Afonso, J.; Castro, H.; Clemente, F.M. External and internal load and their effects on professional volleyball training. Int. J. Sports Med. 2020, 41, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, P.R.; Woods, C.T.; Sweeting, A.J.; Robertson, S. Applications of a working framework for the measurement of representative learning design in Australian football. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loureiro, M.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Ramos, A.; Coutinho, P.; Ribeiro, J.; Clemente, F.M.; Mesquita, I.; Afonso, J. Ongoing Bidirectional Feedback between Planning and Assessment in Educational Contexts: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912068

Loureiro M, Nakamura FY, Ramos A, Coutinho P, Ribeiro J, Clemente FM, Mesquita I, Afonso J. Ongoing Bidirectional Feedback between Planning and Assessment in Educational Contexts: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912068

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoureiro, Manuel, Fábio Yuzo Nakamura, Ana Ramos, Patrícia Coutinho, João Ribeiro, Filipe Manuel Clemente, Isabel Mesquita, and José Afonso. 2022. "Ongoing Bidirectional Feedback between Planning and Assessment in Educational Contexts: A Narrative Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912068

APA StyleLoureiro, M., Nakamura, F. Y., Ramos, A., Coutinho, P., Ribeiro, J., Clemente, F. M., Mesquita, I., & Afonso, J. (2022). Ongoing Bidirectional Feedback between Planning and Assessment in Educational Contexts: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912068